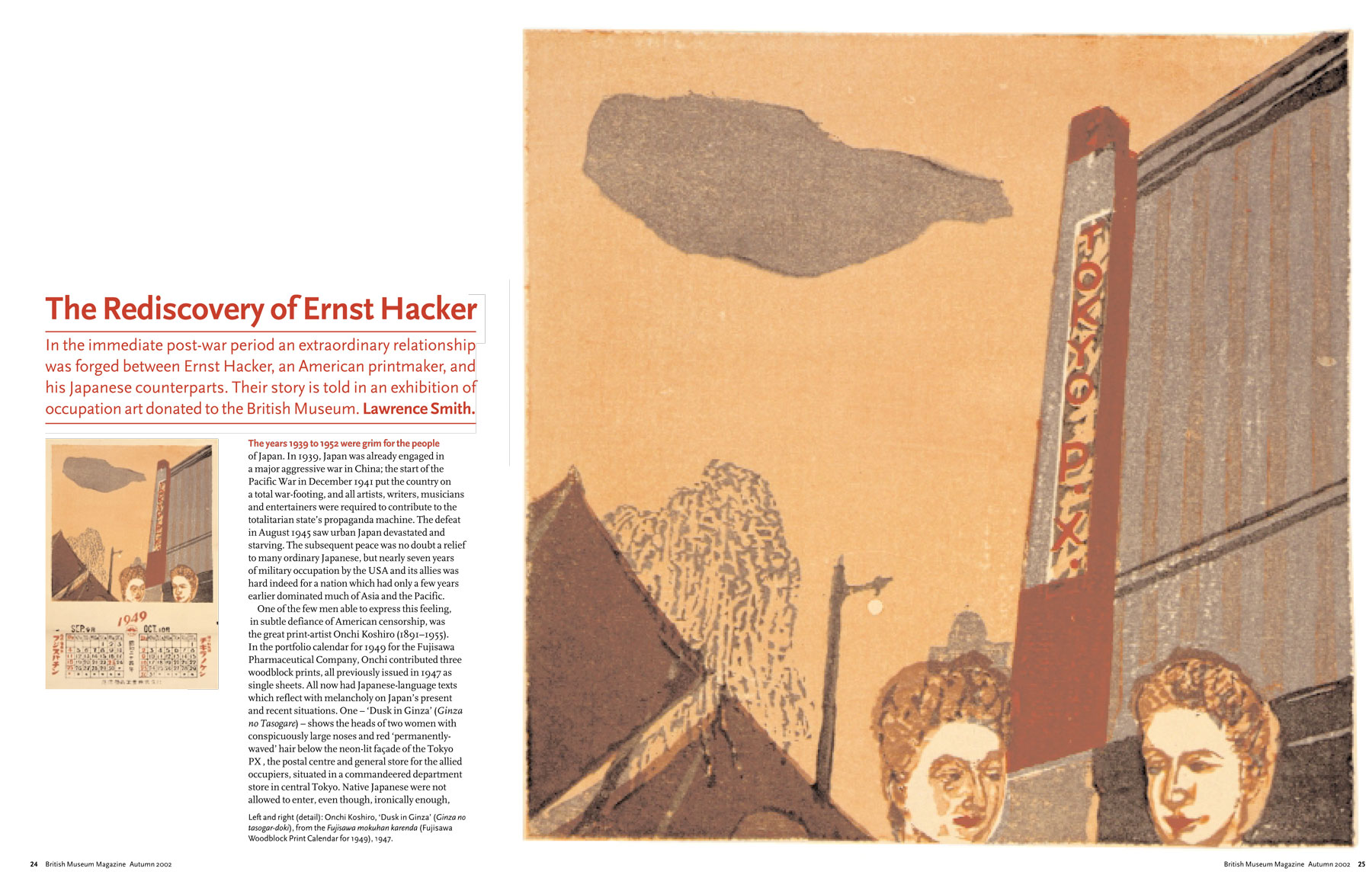

Ernst Hacker 1946 (Hacker Archive, The British Museum) | ProfileErnst Hacker (1917-1987) Source: JapanesePrints During the Allied Occupation 1945-1952, Lawrence Smith, BritishMuseum Press, 2003, p. 7.Ernst Hacker was sent to Japan with the Occupying forces in spring 1946. A printmaker himself, he quickly got to know Onchi Kōshirō (1891-1955), a leader of the Creative Print movement, and through him many other artists. He attended meetings of the First Thursday Society and exhibited at the Japan Print Association, of which Onchi was also the leading member. Hacker's short stay resulted in a collection of prints of the period, many photographs of the Japanese scene, and a long correspondence with the Onchi family. This material and also the extensive collection of prints in books by Onchi and his colleagues reside in the British Museum and form the basis for a reappraisal of one school of Japanese art (sosaku hanga) during the War and Occupation periods. |

Biography

Source: Japanese Prints During the Allied Occupation 1945-1952, Lawrence Smith, British Museum Press, 2003, p. 27-29.

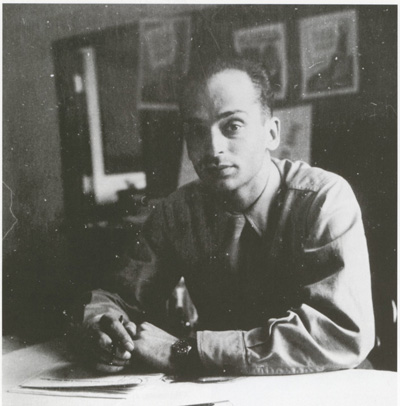

Born in Vienna in 1917 of educated, artistic and liberal Jewish parents Hacker studied art at the Vienna Fine Arts Academy and engineering at the Institute of Technology. In 1938 he fled Nazi controlled Vienna to New York. His early work in New York were expressionist monochrome woodblock prints depicting tragic scenes witnessed in Vienna. In New York he attended the American Artists School where he met his future wife Lucia Vernarelli. (See portrait below.)

c. 1950-60

Color Woodblock Print

His parents joined him in New York by 1939. Late in World War II he gained his US citizenship, was drafted into the army and sent to Manila, where he worked in an art and design group, before being sent to Japan in 1946.

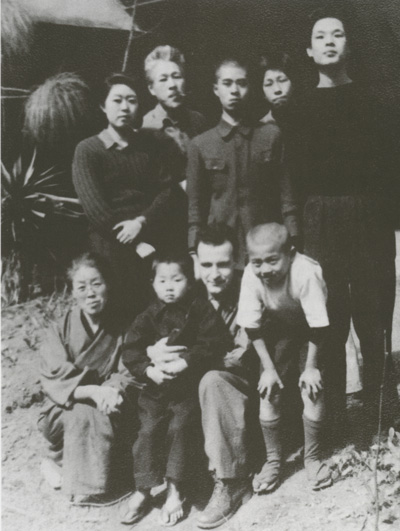

In Tokyo, Hacker produced posters and other graphic material for the Ernie Pyle Theater. He quickly developed an interest in Japanese art-forms. Very soon after his arrival he sought out Japanese print artists and by April had met Onchi Kōshirō (1891-1955), his family and artistic circle.

Hacker Archive, The British Museum

Hacker was able to communicate with Onchi in German and shared a passion for photography with him, which helped build their relationship. He was a frequent visitor to Onchi's house and a valuable friend to Kōshirō and the Onchi family. In his portrait of Hacker, Onchi has inscribed in German "To Mr. Ernst Hacker with thanks for your intimate friendship."

While it is unclear if Hacker ever met Munakata , another major figure in the post-war sosaku hanga movement, in Japan he did acquire a number of Munakata's works and was to meet him in 1955 in New York.

Hacker returned to New York in the Autumn of 1946. He continued to make prints and to exhibit until 1967. He went to live in Florence in 1974 and died in 1987 after a long illness.

Exhibitions

Source: British Museum press release on the website of ArtMag.com http://www.artmag.com/museums/a_greab/british/japan1.html4 September - 1 December 2002

British Museum Japanese Galleries, Admission Free

In 1945 much of urban Japan lay in ruins, the land occupied by foreign powers for the first time in the country's history. To many Japanese it seemed that everything had been lost, but in fact the nation would quickly demonstrate - and on a much larger scale than before - its ability to recover physically, economically and culturally from apparent disaster. With the realization that the Occupation forces were not 'oni' ('demons') but largely benevolent and genial individuals, the concept of a 'New Japan' was quickly promulgated. It was one which had attractions to people who had lived in many cases all their lives under a totalitarian regime. All the visual arts began to benefit almost from the outset, and the years between 1945 and 1952 demonstrated increasing confidence and considerable achievement in painting, calligraphy, prints, ceramics and other media.

This illuminating exhibition examines in detail how one school of printmakers, under the pioneering leadership of Onchi Kōshir (1891-1955), managed to survive the Pacific War and, as artists, found themselves among those calling for a new search for the nation's heart in its aesthetic traditions. Although many continued to suffer from the privations of the war years, they also received unexpected appreciation and support from artists and administrators among the Allied occupying forces.

Symbolic of this process was the meeting of the American graphic artist Ernst Hacker (1917-87), posted to Tokyo in Spring 1946, with Onchi and this circle and Munakata Shikō (1903-75), who was then almost unknown. On joining Onchi's influential printmaking group, 'The First Thursday Society', Hacker's own print style rapidly changed from the monochrome and representational to the richly coloured and abstract idiom which Onchi had been developing. By 1952, when the Allied Occupation ended, Onchi and his circle and Munakata were being eagerly collected in United States and these two, introduced to the world by their American admirers, are now recognized as Japan's greatest print artists of 20th century.

Prints, photographs and other archival material acquired by Ernst Hacker during the post-war years and recently given to the Museum by his widow form the basis of this revealing exhibition.

Source: The New York Times archive

London / EXHIBITION : Cross-cultural encounters in postwar Japan

By Souren MelikianPublished: Saturday, September 28, 2002

This is a story of unlikely encounters and cultural split personalities that could only have happened in the 20th century.

The prelude takes place in Vienna under Nazi rule with Ernst Hacker, a young Austrian from a Jewish family as the central character. In 1938, while still a student at the Academy of Art, Hacker emigrates to New York, where he supports himself as a graphic designer and attends the American Artists School. He meets Lucia Vernarelli, whom he marries, and, having acquired U.S. citizenship, is drafted.

In 1945 Hacker is in Manila, and in 1946 he is posted to Japan. In the half-destroyed capital, the graphic designer seeks out printmakers and meets a famous artist, Onchi Kōshirō, who had studied engineering in Tokyo under German professors. The Jewish refugee from Austria and the Japanese artist communicate in their shared language: German.

Thus began an improbable friendship that would spawn an even more improbable artistic school. Unknown until the current show, "Japanese Prints During the Allied Occupation, 1945-1952" at the British Museum — put together by the curator emeritus Lawrence Smith — the school's work scan be seen in public for the first time (until Dec. 1).

If the immigrant Hacker may at times have felt disoriented, the Japanese were steeped in long-standing cultural schizophrenia, attempting to reconcile the conflicting aesthetics of East and West. In 1938, the year Hacker left Vienna, Onchi made a woodblock print portraying the composer Yamada Kosaku. The figural manner is borrowed from the Western academic tradition, but the bust stands against flat bands of black, ocher and white, abruptly contrasted, in pure Japanese taste.

Also in 1938, Munakata Shikō printed black-and-white portraits in which the influence of Picasso and Matisse's draftsmanship are more evident than the Japanese legacy. A year later, in this experimental atmosphere, Japanese artists who straddled the two worlds and shared an interest in printmaking began to meet on the first Thursday of every month. Their aim was to look together at prints they made solely for themselves, and their group was dubbed "The First Thursday Society."

The house in which they met — designed in 1932 by Endo Arata, a Japanese student of Frank Lloyd Wright — survived the war, as did the society. How Hacker and two buddies, Alonzo Freeman and John Sheppard, came to join it in early 1946 is not known — American soldiers were not permitted to fraternize with Japanese civilians.

Onchi's work was a kaleidoscope of Western avant-garde styles interpreted in sparing Japanese fashion. "Window Open to the Sea," 1941-1944, is an abstract composition on which the linear geometricism of Paul Klee has left its mark. The "sea" is a grayish-blue triangle lodged within the geometrical figure that stands for the "window." A small chair introduces an incongruous figural note.

In "Fairy Tales in the Shell," done in a minimalist manner, tiny curving shapes suggestive of Joan Miro's compositions are jotted in the middle of a blank sheet. Executed in the woodblock print technique, the result greatly differs from the sources that inspired it. Onchi was probably the catalyst of this East-West alchemy — there had never been any sign of abstractionist tendencies in Hacker's art.

Onchi in turn seems to have absorbed influences through Hacker. A strange composition dubbed "Impressionist Portrait of E.H." shows an eye and half the nose of a face (Hacker's) inserted between a curving band of ocher and abstract blue elements. Onchi dedicated it to his new friend.

Western trends of all kinds found echoes in the Japanese woodblock prints. Mori Doshun may have looked at reproductions of Edouard Vuillard's watercolors of the 1890s, while Yamaguchi Gen appears to have been receptive to Matisse's still lifes of the 1920s, hence his "Flowers in a Glass."

There were kitsch images — Yamaguchi Susumu's "Lake Chuzenji" — as well as a few gems. Azechi Umetaro's delightful "Mountain (Yama)" depicts mountains in simplified mauve volumes shaded on one side under a delicate grayish-blue band, the sky. Leafless trees with spiky stumps rhythmically distributed in the foreground send back a distant echo to German Expressionism.

At long intervals, a yearning for the past comes through, as in Tsukamoto Tetsu's landscape handled in the manner of a traditional painter dipping the tip of his brush in black ink. The bird's-eye view, the staccato effect of the short strokes speak of the Japanese tradition rooted in the legacy of Ming China.

One striking masterpiece was produced in the midst of these experiments. Wakayama Yasoji's "Spring" landscape, barely recognizable as such, could be characterized as suggestively figural. Touches of light color conjure up the idea of fields under a cloudy sky, without showing any of it in detail. Irregular shapes in the distance may stand for trees — it is hard to tell. It all looks like impressions remembered from a dream.

Around 1950 Hacker, back in America, produced his ultimate chef d'oeuvre, a portrait of his wife in the pale delicate colors favored by contemporary Japanese printmakers. The serenity that it exudes is far removed from the black images of distress that he had done less than two decades earlier — and kept, in some cases all his life, like the scene of a man he knew in Vienna who had hanged himself.

Yet, he had not altogether given up his Expressionist style of yore. The lonely figure crouching on the sidewalk, titled "New York down-and-out" is an image of despondency, in the style of 1938. Hacker became utterly eclectic. "The Brooklyn Bridge," a print of the 1950s displays, Smith writes, "some residual influence from the city scenes in the Sosaku Hanga style he saw in 1946." Another comparison springs to mind as far as the crowded architectural composition is concerned: the Frenchman Emile Laboureur's views done half a century earlier during a brief trip to New York.

The cultural schizophrenia that the 1946 prints made by Hacker's Japanese friends reveal persisted after his departure, and even after his death, in 1987. It is still there.

As an appendix to the show of the Hacker archive, which was acquired by the British Museum through a gift, a selection of contemporary prints displays greater diversity than ever, even if mostly derivative in nature. Some betray familiarity with the paintings of Serge Poliakoff, conveyed in the delicate tones of Japanese prints. Others illustrate an attempt at recapturing the greatness of Sharaku's portraits in the 1790s. Such is Tsuruya Kokei's scene from the play "Kuruwa Bunsho." All look like stylistic exercises, occasionally elegant and nearly always pointless. Cultural schizophrenia never was the best path to artistic creativity.