Prints in Collection

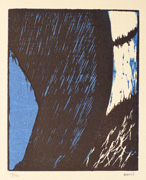

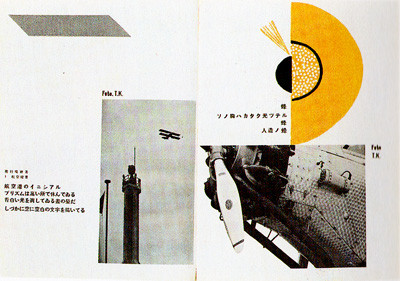

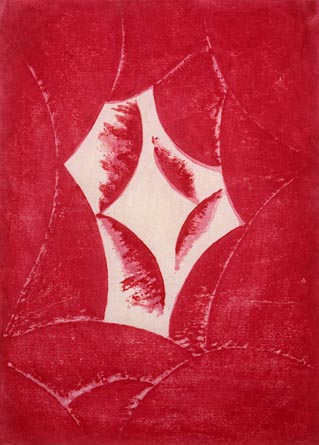

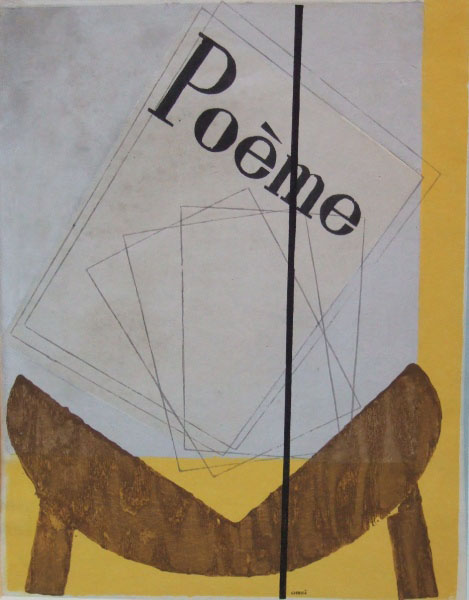

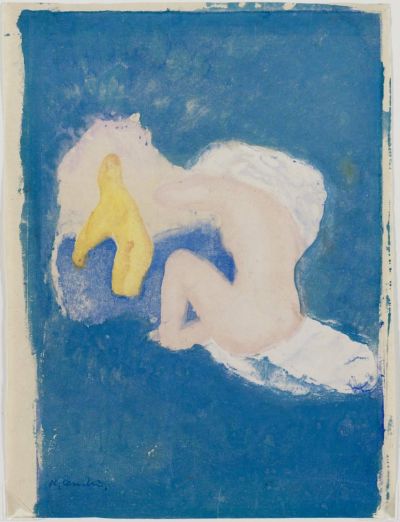

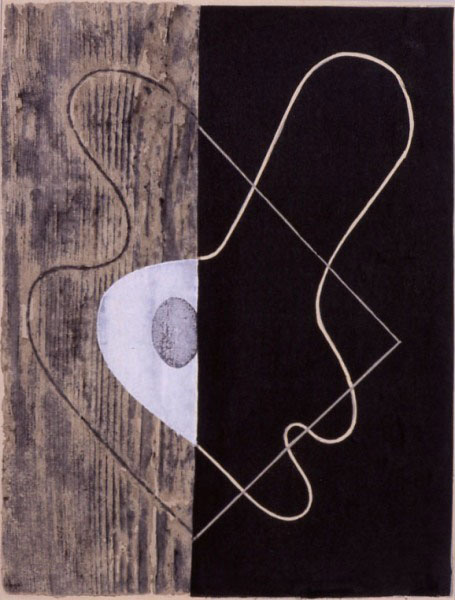

Things Suspended in the Sky, 1914 IHL Cat. #550 |  IHL Cat. #391 | Lyrique: The Truth Only Shines Over, 1915 IHL Cat. #1118 | Untitled, geometric shapes and half-eye, undated IHL Cat. #489 |

IHL Cat. #2039

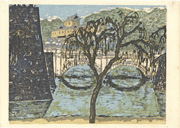

Nijubashi (Bridge to the Imperial Palace) from the series Scenes of Last Tokyo, 1945 IHL Cat. #185 | Ueno Zoo (Ueno Dobutsuen) from the series Scenes of Last Tokyo, 1945 IHL Cat. #169 |

Biographical Data

Profile

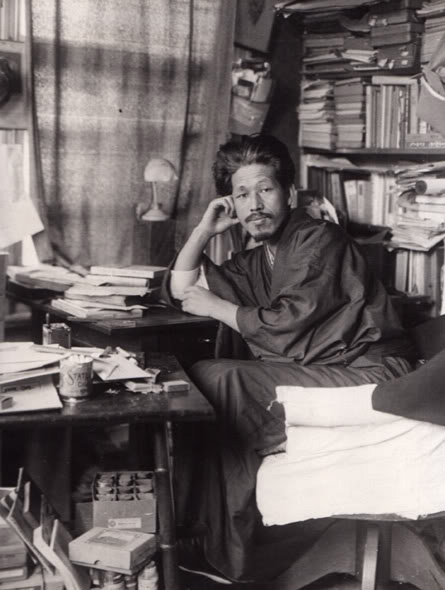

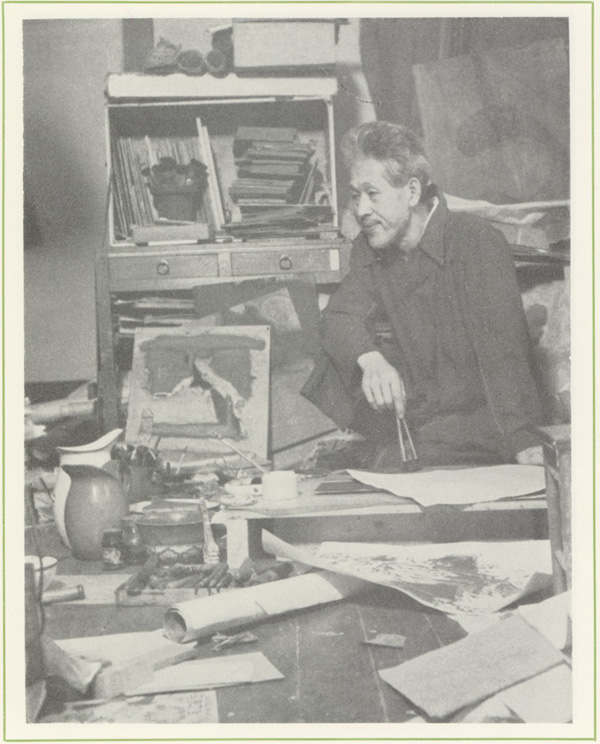

Onchi Kōshirō 恩地孝四郎 (1891-1955)Sources: British Museum website

http://www.thebritishmuseum.ac.uk/compass/ixbin/hixclient.exe?_IXDB_=compass&_IXFIRST_=1&_IXMAXHITS_=1&_IXSPFX_=graphical/full/&$+with+all_unique_id_index+is+$=ENC113096&submit-button=summary; L. Smith, and V. Harris, Modern Japanese prints, 1912-1989 (London, The British Museum Press, 1994); The Graphic Art of Onchi Koshiro -Innovation and Tradition by Elizabeth de Sabato Swinton

Onchi Kōshirō1 is considered one of the leading innovative figures among Japan's twentieth-century artists. He is credited with producing Japan's first purely abstract work Light Time in 1915. He produced single sheet prints and book designs, as well as being a poet and art theorist. He began his career learning oil painting at the Tokyo School of Fine Arts, going on to study sculpture, which he later abandoned. In 1911, under the influence of Takehisa Yumeji (1884-1934), Onchi began to design books and quickly became involved in producing print and poetry magazines. He designed the first edition of Hagiwara Sakutarō's2 (1886-1942) innovative collection of poems Tsuki ni hoeru (Howling at the Moon, 1917).

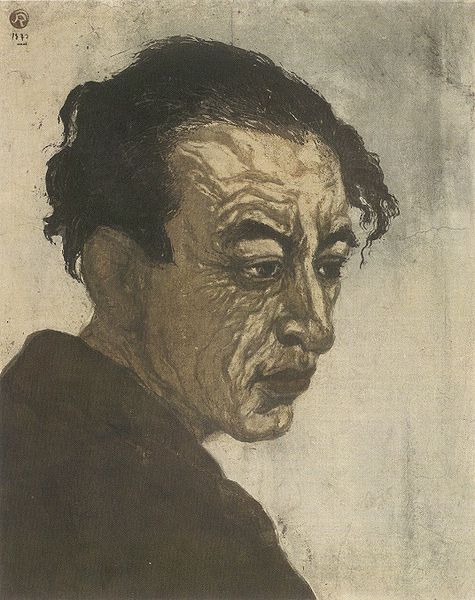

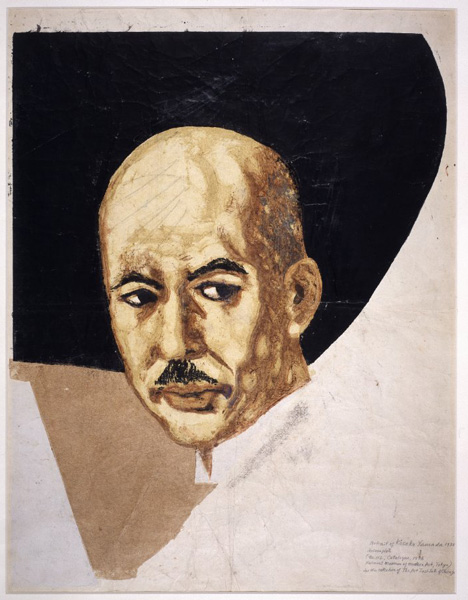

Onchi's contribution both as traditionalist and innovator can best be seen in his single-sheet prints. He was one of the founders of the sōsaku hanga (creative print) movement. Unlike traditional commercial woodblock printmakers, these artists were inspired by painting and carried out every stage of production themselves: designing, cutting, and printing, then circulating the finished works to a relatively small élite circle. Onchi's prints are of four types: the traditional subjects of meisho (famous views) and bijin (beautiful women), portraits and abstracts. One of his most well-known portraits is the psychologically penetrating 1943 study of Hagiwara Sakutarō. Onchi started to make abstract prints at the beginning of the Taishō era (1912-26), and continued to experiment, drawing on traditional elements of Japanese color and decorative sense, combining them with motifs from international modernism. His prints were produced in very small editions, demonstrating his attitude to his works as one-offs, closer in spirit to paintings than to traditional woodblock prints.

ONCHI, Kōshirō 1891 - 1955 ONCHI, Kōshirō 1891 - 1955Light Time, 1915 National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo |  ONCHI, Kōshirō 1891 - 1955 ONCHI, Kōshirō 1891 - 1955Portrait of Hagiwara Sakutarō (1943) National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo |

2 Considered by many to be Japan's greatest lyric poet. His major works of poetry, written in 1917 and 1923, were Howling at the Moon and Blue.

Biography

Source: Floating World website http://www.floatingworld.com/docs/ref_ArtistDetail.asp?art_ID=125 Taken in whole, or in part, with permission from: Merritt, Helen and Nanako Yamada. Guide to Modern Japanese Woodblock Prints: 1900-1975, University of Hawaii Press: Honolulu. 1992, p. 121- 122 and as footnoted.Born in Tokyo in 1891, Onchi was the fourth son of Onchi Tetsuo. He learned calligraphy from his father, a tutor of three young princes who were to marry the Emperor Meiji daughters. He graduated in 1904 from Bancho primary school and in 1909 from the middle school for German studies in Tokyo. After failing the examination to enter Daiichi Kotogakko (First High School), he studied oil painting at the Aoibashi branch of the school of Hakubakai.

In December 1909 he sent his impressions of the artist Takehisa Yumeji's recently published book Yumeji Picture Collection, Spring Volume to the artist and received an encouraging response. Encouraged by Yumeji, Onchi entered the Tokyo School of Fine Arts in 1910, first studying oil painting and then sculpture. In 1911 he withdrew from the school and through his friendship with Yumeji obtained a job as a book designer with Kawamoto Kamenosuke of Rakuyodo. In 1912 he was readmitted to the Tokyo School of Fine Arts.

In October 1913, with fellow students Tanaka Kyokichi and Fujimori Shizuo (1891-1943), he began planning the print and poetry magazine Tsukuhae (Moonglow). He personally created numerous abstract prints for the publication and directed the publication of seven issues from 1914-1915. He collaborated with Tanaka Kyokichi during the last months of the latter’s terminal illness on illustrations for Howling at the Moon (Tsuki ni hoeru), a book of poems, by Hagiwara Sakutarō, published 1917. In 1916 he joined the poets Muroo Saisei and Hagiwara Sakutarô in producing the poetry magazine Kanjo. Onchi contributed cover designs, poems, and woodblock prints. Kanjo continued publication for 32 issues until November 1919. In 1917 Onchi published his first collection of prints, Happiness (Kofuku). In 1919 he participated in the first Nihon Sosaku-Hanga Kyokai exhibition and in 1921 began publication of the general art magazine Naizai with Otsuki Kenji and Fujimori Shizuo (1891-1943). Over the years Onchi was also active in producing and promoting other poetry and print magazines to which he contributed poems, prints, graphic design, and articles promoting the idea that printmaking is a legitimate expressive and creative medium, not merely a means of reproduction. Onchi contributed prints to Minato, Kaze, Shi to hanga, Dessan, HANGA, Shiro to kuro, Han geijutsu, and Kitsutsuki and to numerous collective series. He was a member, leader and mentor in Nihon Sosaku Hanga Kyokai and Nihon Hanga Kyokai. He exhibited prints in Teiten (a government sponsored exhibition) and Kokugakai (National Painting Association).

By 1927 Onchi had established a reputation as a book designer. In 1928, in the wake of Lindbergh’s trans-Atlantic flight, he was engaged by a newspaper company to go up in a plane and record his impressions of flight. The resulting book, Sensations of Flight (Hiko kanno), 1934, became a seminal work in book design in Japan.

From 1935 to 1944 he edited 103 issues of the monthly magazine Shosō 書窓 (Window of Writing). This magazine on the art of the book set the standard of excellence for Japanese graphic design. He also personally designed over 1,000 books for publishers. He self-published several books of his own poems or prose with illustrations, among them Fairy Tale of the Sea (Umi no dowa) in 1934, and, in 1935, A Diary of Random Thoughts (Zuiso nikki). In 1949 received the first prize offered in Japan for book design.

In the midst of his busy professional career in 1938 he contributed to the print series One Hundred Views of New Japan (Shin Nihon hyakkei). From 1939 throughout World War II and after, he maintained Ichimokukai (The First Thursday Society), a monthly meeting of hanga artists. As with many artists, Onchi was pressed into national service during WWII and served as the chairman of the Japanese Public Service Association (Nihon Hanga Hōkōkai) from 1942.1 Following WWII, he organized, contributed three prints and wrote the introduction to the 1945 print portfolio Scenes of Last Tokyo (Tokyo kaiko zue) in an effort to revitalize woodblock printing in the war's immediate aftermath.

Onchi was active in progressive art organizations after the war including the League of Japanese Artists (Nihon Bijutsuka Renmei), the Japan Abstract Art Club (Nihon Abusutorakuto Ato Kurabu), and the International Print Association (Kokusai Hanga Kyokai). He was a major force in the sōsaku hanga movement and the leading abstract print artist of his time in Japan.

Onchi died on July 3, 1955 at the age of 63 after being hospitalized in April for a disturbance of the central nervous system.2

1 Since Meiji: Perspectives on the Japanese Visual Arts, 1868-2000, edited by J. Thomas Rimer, University of Hawai'i Press, 2012, p. 382.

“Sofar as the classical ukiyo-e artists are concerned I feel positively no relation to them and no debt to them whatever. Today our attitudes toward art are completely different. In forming my judgments I ignored all classical Japanese work and stepped right into the main stream of European art. It is true that the prints which Kanae Yamamoto did while he was in Holland showed me what could be accomplished with the medium and pleased me very much, but my teachers were the Norwegian Edvard Munch and the Russian-German Wassily Kandinsky.”

Source: "Thoughts on Onchi Koshiro," Kubo Sadajiro, appearing in Prints of Onchi Koshiro, Keishosha Ltd., 1975, p. 234.

"When one of his friends called him a dilettante, Onchi answered as follows:

last revision:

2 Prints of Onchi Koshiro, Keishosha Ltd., 1975, p. 323.

"Woodblock prints are pictures which are produced by carving a picture which is drawn by engraving with a sharp-edged tool. Therefore it is very distinctive. Through its essential form, it brings out the ideas of the maker. It is a picture in which the pigment is imprinted on the picture surface and becomes an integral part of the print; a picture you cannot paint over or correct; each line, each color depends on a conscious decision by the artist. This is the essence of woodblock pictures. This accuracy is a particular characteristic of the technique. The limitations of the technique results in increased control by the artist. A careless and casual manner has no place in woodblock prints which have integrity and lack deception. The technique is precise but variations that permit you to avoid punctiliousness and over exactness are possible; for example, engraving with short oblique cuts or in continuous and unbroken lines, gradations in printing, etc.; this perhaps is its greatest artistic refinement."

"Six copies is about the maximum he has ever made of any print, one being the usual number. Since he often prints from the initial block, then gouges it to make the second block, it is obvious that many of his prints can never be reissued. He has experimented with positively every conceivable kind of material, some of his finest work resulting from hastily cut paper stencils which when brushed vigorously yield a smeared line along the edges. He seems to have a savage contempt for the old traditions of ukiyo-e as if they were a jail from which he had broken with considerable effort."

(Note: Michener estimated that in 1954 a “first-class print by Onchi” cost 8000 yen, or $22.00.)

In his notes on Onchi's print Poème No. 7: Landscape of May, Lawrence Smith of the British Museum states:

"The post-war demand among American and European collectors for impressions of the Hagiwara image [Portrait of Hagiwara Sakutarō (1943)] was intense, but Onchi produced very few impressions (probably between 13 and 15 over several years). Then, in 1949, Sekino Jun'ichirō printed an edition of 50 impressions after some guidance from Onchi. In addition, a posthumous memorial edition of undocumented size was commissioned by Onchi's family and printed in 1955 by Hirai Kōichi. Finally, in 1987, Onchi's son Kunio printed 10 more impressions from the original blocks; seven went to museums and two are in private collections, while the location of the remaining impression is currently unconfirmed."3

The Artist's Woodblock Prints - A Few Examples

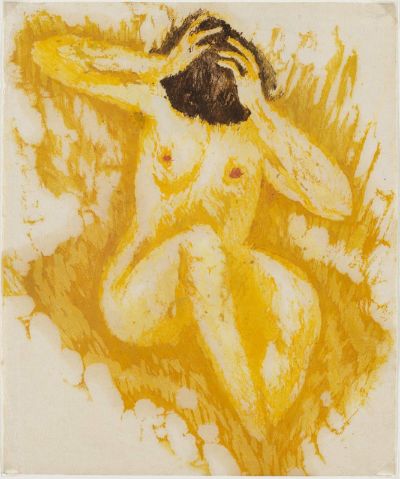

Note: The signature ONZI is sometimes seen on the artist's early prints.  Nude Tones of Yellow (1914) |  Composition No. 2 Character (1915) |  Bathers (1928) |

(1938) |  (1947) |  (1950) |

Onchi's Definition of Woodblock Prints

Source: The Graphic Art of Onchi Koshiro - Innovation and Tradition, Elizabeth de Sabato Swinton, Garland Publishing, Inc., 1986"Woodblock prints are pictures which are produced by carving a picture which is drawn by engraving with a sharp-edged tool. Therefore it is very distinctive. Through its essential form, it brings out the ideas of the maker. It is a picture in which the pigment is imprinted on the picture surface and becomes an integral part of the print; a picture you cannot paint over or correct; each line, each color depends on a conscious decision by the artist. This is the essence of woodblock pictures. This accuracy is a particular characteristic of the technique. The limitations of the technique results in increased control by the artist. A careless and casual manner has no place in woodblock prints which have integrity and lack deception. The technique is precise but variations that permit you to avoid punctiliousness and over exactness are possible; for example, engraving with short oblique cuts or in continuous and unbroken lines, gradations in printing, etc.; this perhaps is its greatest artistic refinement."

Print Editions

Self-Limiting Numbers

Source: The Floating World, James Michener, Random House, 1954, p. 252"Six copies is about the maximum he has ever made of any print, one being the usual number. Since he often prints from the initial block, then gouges it to make the second block, it is obvious that many of his prints can never be reissued. He has experimented with positively every conceivable kind of material, some of his finest work resulting from hastily cut paper stencils which when brushed vigorously yield a smeared line along the edges. He seems to have a savage contempt for the old traditions of ukiyo-e as if they were a jail from which he had broken with considerable effort."

(Note: Michener estimated that in 1954 a “first-class print by Onchi” cost 8000 yen, or $22.00.)

Memorial Editions

After Onchi's death, his family authorized memorial editions of a number of his prints to be created by the professional printer Hirai Kōichi 平井孝一. Various editions of the same prints were printed by Hirai into the 1960s. The print in this collection Impression of a Violinist (Portrait Of Suwa Nejiko) is a Hirai memorial edition printing. Statler, in his preface to the Onchi catalog raisonné, says of Hirai that he "was a sensitive professional artisan who was sympathetic to the sosaku hanga artists; he brought to his assignment skill and dedication."1In his notes on Onchi's print Poème No. 7: Landscape of May, Lawrence Smith of the British Museum states:

"Since Onchi’s death, the professional printer Hirai Kōichi has been commissioned to print an indefinite number as a memorial edition. As with the portrait of Hagiwara [Hagiwara Sakutaro] and several others, a memorial edition was made after Onchi's death by Hirai based on the original blocks but considerably tidied up, and with clear, simple, elegant colours far removed from the artist's turbulent, impassioned tones, which recall the effects of brush and oil paint rather than woodblock."2

In regards to Onchi's famous 1943 portrait of Hagiwara Sakutarō [see image above], John Fiorillo states:

In regards to Onchi's famous 1943 portrait of Hagiwara Sakutarō [see image above], John Fiorillo states:

1 Prints of Onchi Koshiro, Keishosha Ltd., 1975, p. 30.

2 British Museum website note by Lawrence Smith

3 John Fiorillo website Viewing Japanese Prints https://www.viewingjapaneseprints.net/texts/sosaku_hanga/onchi.html

3 John Fiorillo website Viewing Japanese Prints https://www.viewingjapaneseprints.net/texts/sosaku_hanga/onchi.html

Other Editions

Onchi's son Kunio reprinted a number of his father's works posthumously, as did the printer Yoneda Minoru, whose imprint appears on three prints in this collection, Things Suspended in the Sky, Yearning Afterward and Untitled, geometric shapes and half-eye. Yoneda also printed for Sekinō Jun’ichiro (1914-1988) and reprinted works of Maeda Masao (1904-1974).Onchi's View on Ukiyo-e

Source: The Floating World, James Michener, Random House, 1954, p. 249“Sofar as the classical ukiyo-e artists are concerned I feel positively no relation to them and no debt to them whatever. Today our attitudes toward art are completely different. In forming my judgments I ignored all classical Japanese work and stepped right into the main stream of European art. It is true that the prints which Kanae Yamamoto did while he was in Holland showed me what could be accomplished with the medium and pleased me very much, but my teachers were the Norwegian Edvard Munch and the Russian-German Wassily Kandinsky.”

Onchi's Self-Reflections

1922Source: "Thoughts on Onchi Koshiro," Kubo Sadajiro, appearing in Prints of Onchi Koshiro, Keishosha Ltd., 1975, p. 234.

"When one of his friends called him a dilettante, Onchi answered as follows:

| I define the word 'dilettante' as 'art lover.' And I am nothing more than that. Because the word 'artist' means a great deal, I dare not call myself an artist. I am too conscious of my own shortcomings. What differentiates an artist from a dilettante is the quality and solidity of inner life. One who can declare, 'I am an artist, not a dilettante,' is either an idiot or a genius. I am not in the latter category. If in the future what I try to create adds something to the lives of a few people, I might be even accepted as a 'small' artist. But this has nothing to do with me really. My only wish is to express what I want to say on as high a level as possible and concentrate my entire soul into my work." |

1953

Source: "Onchi Koshiro's Pursuit of Modernity in Prints 1920s-1930s," Kuwahara Noriko, article appearing in Hanga: Japanese Creative Prints, Art Gallery of New South Wales, 2000, p. 23.

In 1953, the 62-year-old Onchi Kōshirō, looking back at his 40 years of artistic activities, wrote his brief autobiography as one of the print artists in his book Nihon-no Gendai Hanga (Japanese Contemporary Prints):

"A definition of Onchi's style must be broad because of his personal eclecticism. Although he was able to work in a variety of artistic modes and idioms, his temperament was selective. All of his models were not equally suited to his interests, and when he did respond to a visual idea, he often took it far from its original source in interpretation. His intense preoccupation with the print medium and with technique as a vehicle of artistic expression was shaped by the artistic conventions of Japanese calligraphy with its emphasis on discipline, control and the integrated dynamic relationship between shape, line and color (tone) and their ground. He frequently used the formal elements of art symbolically, tying them to specific events or images in the world of the senses evoked through verbal associations.

Onchi turned to prints because the medium, in which the artist could continue to make changes until he achieved the perfect expression of his idea, seemed more responsive to his artistic needs than painting, but he used the print technique as a painter, creating single not replicative images, using the baren with the idiomatic force of the brush and color as his most expressive element. He turned to prints as he turned to abstraction because they increased his expressive range."

"Only Onchi went ahead of his time and attempted to build a bridge to the future. He tried to proclaim the independence of abstract art with intense conviction and yet with delicate sensitivity. He tried to unveil the mystery of the universe, and in so doing he became part of the mystery and immortalized his creations."1

1 "Thoughts on Onchi Koshiro," Kubo Sadajiro, appearing in Prints of Onchi Koshiro, Keishosha Ltd., 1975, p. 234.

"The years since Koshiro Onchi's death have brought him the honor as an artist which was denied during his lifetime. This is the classic story of fame after death, but it has particular poignancy in Onchi's case because recognition came so swiftly after he died: it seems to have been waiting in the wings for that determinant cue.

I think he would have enjoyed a little glory, for he had fought a long, hard fight not only for himself but for his fellow artists. But I do not think it would have changed his work or his life. He was not cursed by poverty; he made a comfortable living as a designer of fine books. And as artist he was always true to himself. Unlike men of shifting values, he always knew what was important to him and he knew what he believed in.

He believed that the print is an important and rewarding medium, worthy of as much attention as painting. And he believed in abstract art. (The term 'abstract art' has gone out of style these days in favor of newer expressions, but it was not out of style in Onchi's time and place.)

'Abstract art is now, as it should be, the main way of art,' he wrote. 'I hope our civilization soon comes to realize this.' When he said this he was not really advocating the importation of a Western mode into Japanese art. There is a vital strain of the abstract in Japanese art from its ancient beginnings. It shows for example, in kimono design, in garden architecture, and in painting.

Onchi saw kinship between abstract art and the print. In abstract work, he said, the important thing is composition, construction. And the print embodies 'the most constructive process in graphic art, the advantage of superimposing images. For this reason the print is probably the most suitable method yet found for the expression of modern art.'

Onchi saw other virtues in the print, and particularly in the woodcut, virtues characteristic of the man. 'The virtue of the print lies in the certainty that it comes from a creative process which permits no sham. Unlike brush painting it permits no wavering of the hand. It is honest - sham and error show. Some liberty may be allowed in the registry but so little that the printing, like the carving is a process which permits no delusion.... The print rejects ornamentation and it rejects the accidental.'

Onchi was a rebel. His was from an aristocratic family, and in becoming an artist he rebelled against all notions of a proper career for one of his station. In art he rebelled against all convention in choosing to become a print maker. In prints he rebelled against all tradition by working boldly and freely, with high disdain for the meticulous precision which was the hallmark of old Japanese prints.

Onchi was a leader. He might have made more prints if so much of his energy had not been drained in leading the print artists' fight against the hostile bureaucracy of Japan's art world; but it was a job nobody else could do because none of the other print artists had the requisite family status. And he might have worked more carefully if he had not been so conscious of the need to blast the finical traditions of a tired old craft; but here his strength and his weakness are inseparable and in his finest prints the issue never arises.

Rebel and leader, Onchi was pivotal artist. All of contemporary Japanese art is different because of him. He gave new freedom and new vitality. He pointed to new directions which will be explored for years to come.

Onchi himself said that his great influences were all European - he named especially Kandinsky and Munch - and yet as the years go by his prints look more and more Japanese. His design, his color, his lyricism, all seem rooted deep in Japan, as he was. Especially Japanese is his passion for fugitive beauty, for the beauty of transient materials, for the fleeting beauty of the moment already gone.

Something of Onchi's legacy can be sensed from a statement by a younger artist, Gen Yamaguchi. He said: 'What Onchi taught me was the attitude of an artist, the attitude becoming to an artist. I remember that years earlier I had seen an old cracked tile. I thought it was beautiful and wondered why such elements couldn't be incorporated into art. In Onchi's work I found acceptance of this and much more and a door was opened for me.'

In The Immoralist Andre Gide put the same thought another way: "I have always thought that great artists were those who dared to confer the right of beauty on things so natural that people say on seeing them, 'Why did I never realize before that that was beautiful too?'"

The Graphic Art of Onchi Koshiro - Innovation and Tradition, Elizabeth de Sabato Swinton, Garland Publishing, Inc., 1986

Koshiro Onchi 1891 - 1955 Woodcuts July 11-September 20, 1964, exhibition catalog, Achenback Foundation for Graphic Arts, 1964

Modern Japanese Woodblock Prints - The Early Years, Helen Merritt, University of Hawaii Press, 1990, p. 178-199.

Prints of Onchi Koshiro, Keishosha Ltd., 1975. (a limited edition of 170 copies)

Source: "Onchi Koshiro's Pursuit of Modernity in Prints 1920s-1930s," Kuwahara Noriko, article appearing in Hanga: Japanese Creative Prints, Art Gallery of New South Wales, 2000, p. 23.

In 1953, the 62-year-old Onchi Kōshirō, looking back at his 40 years of artistic activities, wrote his brief autobiography as one of the print artists in his book Nihon-no Gendai Hanga (Japanese Contemporary Prints):

| Onchi Koshiro: He has come away from figurative expression and is working almost entirely in abstraction. He first adopted non-figurative expression in the 1920s, but he has taken a long way round due to his timid nature, which made him conform to people around him. His work as a book designer, from which he earned a living, seemed to have maintained this trend. The Lyric series which he published in Tsukuhae (Moonglow), the magazine of poetry and prints, is said to have heralded a new style. Also his stint in poetry is the reason that his prints are imbued with poetic charm. |

Onchi's Style

Source: The Graphic Art ofOnchi Koshiro - Innovation and Tradition, Elizabeth de Sabato Swinton, Garland Publishing, Inc.,1986 and as footnoted."A definition of Onchi's style must be broad because of his personal eclecticism. Although he was able to work in a variety of artistic modes and idioms, his temperament was selective. All of his models were not equally suited to his interests, and when he did respond to a visual idea, he often took it far from its original source in interpretation. His intense preoccupation with the print medium and with technique as a vehicle of artistic expression was shaped by the artistic conventions of Japanese calligraphy with its emphasis on discipline, control and the integrated dynamic relationship between shape, line and color (tone) and their ground. He frequently used the formal elements of art symbolically, tying them to specific events or images in the world of the senses evoked through verbal associations.

Onchi turned to prints because the medium, in which the artist could continue to make changes until he achieved the perfect expression of his idea, seemed more responsive to his artistic needs than painting, but he used the print technique as a painter, creating single not replicative images, using the baren with the idiomatic force of the brush and color as his most expressive element. He turned to prints as he turned to abstraction because they increased his expressive range."

"Only Onchi went ahead of his time and attempted to build a bridge to the future. He tried to proclaim the independence of abstract art with intense conviction and yet with delicate sensitivity. He tried to unveil the mystery of the universe, and in so doing he became part of the mystery and immortalized his creations."1

1 "Thoughts on Onchi Koshiro," Kubo Sadajiro, appearing in Prints of Onchi Koshiro, Keishosha Ltd., 1975, p. 234.

Oliver Statler's Reflections

Source: "An Introduction," Oliver Statler, from the exhibition catalog Koshiro Onchi 1891 - 1955 Woodcuts, Achenback Foundation for Graphic Arts, 1964"The years since Koshiro Onchi's death have brought him the honor as an artist which was denied during his lifetime. This is the classic story of fame after death, but it has particular poignancy in Onchi's case because recognition came so swiftly after he died: it seems to have been waiting in the wings for that determinant cue.

I think he would have enjoyed a little glory, for he had fought a long, hard fight not only for himself but for his fellow artists. But I do not think it would have changed his work or his life. He was not cursed by poverty; he made a comfortable living as a designer of fine books. And as artist he was always true to himself. Unlike men of shifting values, he always knew what was important to him and he knew what he believed in.

He believed that the print is an important and rewarding medium, worthy of as much attention as painting. And he believed in abstract art. (The term 'abstract art' has gone out of style these days in favor of newer expressions, but it was not out of style in Onchi's time and place.)

'Abstract art is now, as it should be, the main way of art,' he wrote. 'I hope our civilization soon comes to realize this.' When he said this he was not really advocating the importation of a Western mode into Japanese art. There is a vital strain of the abstract in Japanese art from its ancient beginnings. It shows for example, in kimono design, in garden architecture, and in painting.

Onchi saw kinship between abstract art and the print. In abstract work, he said, the important thing is composition, construction. And the print embodies 'the most constructive process in graphic art, the advantage of superimposing images. For this reason the print is probably the most suitable method yet found for the expression of modern art.'

Onchi saw other virtues in the print, and particularly in the woodcut, virtues characteristic of the man. 'The virtue of the print lies in the certainty that it comes from a creative process which permits no sham. Unlike brush painting it permits no wavering of the hand. It is honest - sham and error show. Some liberty may be allowed in the registry but so little that the printing, like the carving is a process which permits no delusion.... The print rejects ornamentation and it rejects the accidental.'

Onchi was a rebel. His was from an aristocratic family, and in becoming an artist he rebelled against all notions of a proper career for one of his station. In art he rebelled against all convention in choosing to become a print maker. In prints he rebelled against all tradition by working boldly and freely, with high disdain for the meticulous precision which was the hallmark of old Japanese prints.

Onchi was a leader. He might have made more prints if so much of his energy had not been drained in leading the print artists' fight against the hostile bureaucracy of Japan's art world; but it was a job nobody else could do because none of the other print artists had the requisite family status. And he might have worked more carefully if he had not been so conscious of the need to blast the finical traditions of a tired old craft; but here his strength and his weakness are inseparable and in his finest prints the issue never arises.

Rebel and leader, Onchi was pivotal artist. All of contemporary Japanese art is different because of him. He gave new freedom and new vitality. He pointed to new directions which will be explored for years to come.

Onchi himself said that his great influences were all European - he named especially Kandinsky and Munch - and yet as the years go by his prints look more and more Japanese. His design, his color, his lyricism, all seem rooted deep in Japan, as he was. Especially Japanese is his passion for fugitive beauty, for the beauty of transient materials, for the fleeting beauty of the moment already gone.

Something of Onchi's legacy can be sensed from a statement by a younger artist, Gen Yamaguchi. He said: 'What Onchi taught me was the attitude of an artist, the attitude becoming to an artist. I remember that years earlier I had seen an old cracked tile. I thought it was beautiful and wondered why such elements couldn't be incorporated into art. In Onchi's work I found acceptance of this and much more and a door was opened for me.'

In The Immoralist Andre Gide put the same thought another way: "I have always thought that great artists were those who dared to confer the right of beauty on things so natural that people say on seeing them, 'Why did I never realize before that that was beautiful too?'"

Literature

Modern Japanese prints, 1912-1989, L. Smith, and V. Harris, The British Museum Press, 1994The Graphic Art of Onchi Koshiro - Innovation and Tradition, Elizabeth de Sabato Swinton, Garland Publishing, Inc., 1986

Koshiro Onchi 1891 - 1955 Woodcuts July 11-September 20, 1964, exhibition catalog, Achenback Foundation for Graphic Arts, 1964

Modern Japanese Woodblock Prints - The Early Years, Helen Merritt, University of Hawaii Press, 1990, p. 178-199.

Prints of Onchi Koshiro, Keishosha Ltd., 1975. (a limited edition of 170 copies)

last revision:

8/23/2021

3/9/2019