Prints in Collection

Biographical Data

Biography

Hatsuyama Shigeru 初山滋 (1897-1973)

Sources: Modern Japanese Prints: An Art Reborn, Oliver Statler, Charles E. Tuttle Company, 1956, p. 99-100; Guide to Modern Japanese Woodblock Prints: 1900-1975, Helen Merritt, University of Hawaii Press, 1992, p. 31 and as footnoted.

Primarily known as an illustrator of children's books, Hatsuyama (also seen listed as Hatuyama) was also a successful sosaku hanga artist featured in Oliver Statler's seminal work Modern Japanese Prints1, from which most of this biography is taken.

| Born in Asakusa, Tokyo, in 1897, Hatsuyama was primarily raised by his mother who encouraged the young Hatsuyama in his love of drawing. At the age of eight Hatsuyama briefly studied yamato-e (Japanese style) painting under Araki Tanrei (1857-1931), a Kano-school painter in Yanaka (Tokyo), but as he was later to relate to Statler, "I was much too young to study art, and since about all my teacher did was give me some of his work to copy, we had a very unsatisfactory year together." At the age of nine he left elementary school and was apprenticed first to a goldsmith (who he ran away from after three months) and then to a fabric dyeing shop in Kanda-Imagawabashi where he stayed five years. During his apprenticeship his passion for drawing continued but, as he told Statler, "no one at the shop would even look at my drawings." He recalls being told by the dyers, "If |

Through a zen priest at a local temple, he was introduced to newspaper and book illustrator Igawa Sengai (1876-1961) and became one of Sengai's student employees. During his time with Sengai he joined a study-group of Japanese-style painters which included the famous shin hanga artist Shinsui Ito (1898-1972).

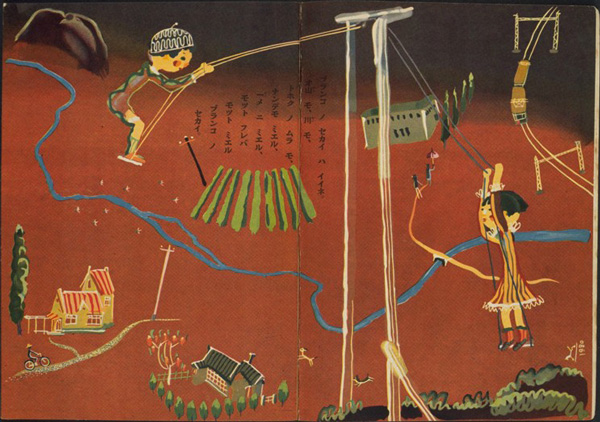

Buranko (Swing) by Hatuyama Shigeru from the magazine Kodomo no kuni (Land of Children) Vol. 9, No. 5, publication of which began in 1920s Japan. It shows examples of the outstanding artwork, songs, and tales that flowered in this magazine under the influence of the Modernist movement. Source: The International Library of Children's Literature / National Diet Library | In 1916, at the age of nineteen, he left Sengai's employ and began living with the kabuki actor Shuchō Bandō III for whom he did varied tasks, even trying his hand, unsuccessfully, at acting. After several years in Shuchō's employ he went back to fabric dyeing, reaching an understanding with his employer that he would be allowed time to study art. During the two years he spent at the dye shop Hatsuyama got his first exposure to woodblock prints from one of the dyers made woodblock prints as a hobby. During the time working for Shuchō and at the dye shop, Hatsuyama regularly submitted his drawings to periodicals and was regularly turned down, but in 1919 he was hired as an illustrator for the children's magazine Otogi no sekai (Fairy World), which he contributed to until its closing in October 1923. As Hatsuyama explained to Statler, "The salary wasn’t enough to feed the family – my mother and young brother and me – and there were some rough times, but I got my start then and I’ve been doing children’s illustrations ever since." |

Hatsuyama goes on to say: “I started prints at about the same time. A publisher who lived in our neighborhood, Ryōji Kumata (1899-1982) (a.k.a. Ryōji Chōmei), was enthusiastic about creative (sosaku) hanga and as a hobby put out a magazine of creative prints called Han Geijutsu (Print Art), often doing the printing himself from artists’ blocks. At his urging I made my first prints. The magazine was never a commercial success, but it did a great deal to encourage modern prints.”

In the mid-thirties, as Japanese society became more and more militarized, he stopped making illustrations (including his serialized illustrated stories in the Tokyo Asahi Shinbun) because he objected to creating propaganda pictures for children, and he devoted his energy to prints instead. He was a member of Onchi Kōshirō's (1891-1955) Ichimokukai (First Thursday Society), formed in 1939, and in 1944 he became a member of the Nihon Hanga Kyôkai (Japan Print Association.) After the war he went back to illustrating and book design but remained active as a woodblock print artist, concentrating on pictures for children or with children as subjects.

Hatsuyama passed away on February 12, 1973 after being hospitalized for burns suffered in a fire at his home.2

1 Modern Japanese Prints: An Art Reborn, Oliver Statler, Charles E. Tuttle Company, 1956.

2 Wikipedia Japan http://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E5%88%9D%E5%B1%B1%E6%BB%8B

Hatsuyama's Woodblock Prints

Sources: Modern Japanese Prints: An Art Reborn, Oliver Statler, Charles E. Tuttle Company, 1956, p. 99-101 and as footnoted.''People consider my prints poor, but my pigments excellent,” he says cheerfully, and while the first half of his remark is colored by modesty, it is true that, perhaps from a respect born in the dyeing shops, he pays particular attention to his pigments, some of which are very special. One color which is almost a hallmark of his prints is the blue called ai, a vegetable pigment made from the plant of the same name. It is one of Japan’s traditional pigments, but hard to get in fine quality. Hatsuyama has a supply form the day when he was doing Japanese-style painting. The color was too dull for brush painting, but has great beauty in prints.

Hatsuyama Shigeru

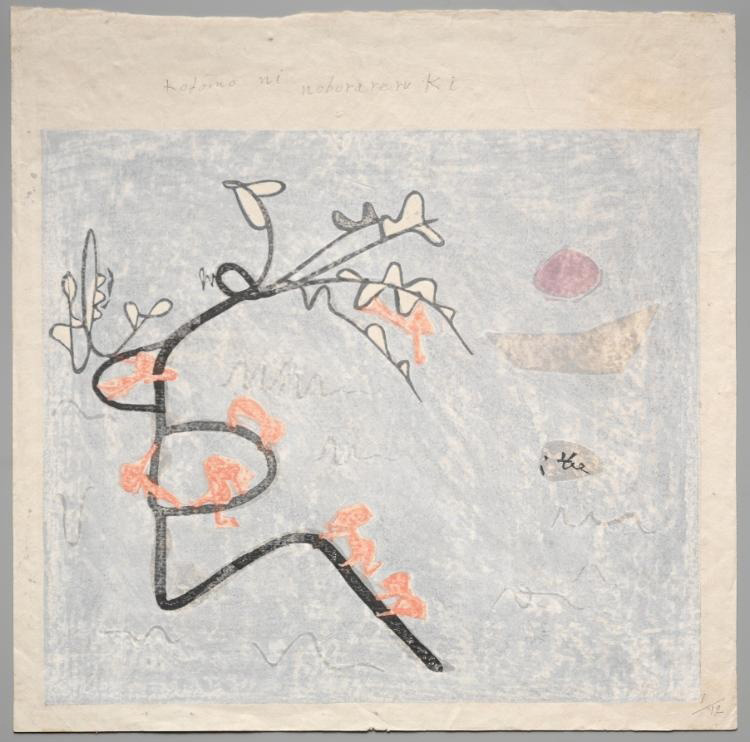

Kotomo Ni Noborareru Ki, 1960 (40x40cm)

Cleveland Museum of Art Accession No.: 2003.315

Kotomo Ni Noborareru Ki, 1960 (40x40cm)

Cleveland Museum of Art Accession No.: 2003.315

He applies the pigment to his blocks with a soft, thick painter’s brush rather than the usual stiff brush, and uses a variable, often very light, pressure when printing. Many of his prints are made from a single, progressively carved block, additional cutting being done before each new printing stage. This means that the first printing is also the last, for the block as it ends up can be used to print only the final stage. “The block is the most beautiful thing in the whole process,” he says. “After it the print is often a disappointment.”

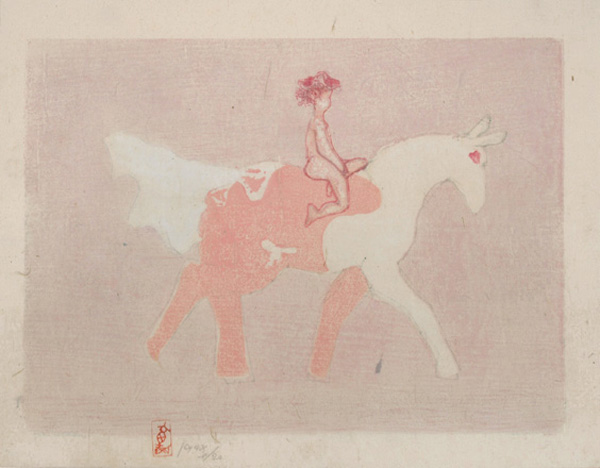

| Hatsuyama Shigeru, The White Horse, 1948 Kikai Gallery | Most of Hatsuyama’s prints fall into a realm of elfin fantasy created in delicate line and color. They are light and gay, with none of the psychological overtones of surrealism. Only once has his fantasy been barbed; in the period of shortages just after the war ended, all the unavailable things he craved were conjured up in a print called Studio of Want. He particularly likes to interpret humans in terms of plants and animals and vice versa, as in Flower, Birds. Other especially successful prints are The White Horse, Japanese Lanterns, The Crying Tree, and a series called Children’s Games. He himself attributes the strain of fantasy in his prints to his work as an illustrator for children. “It takes an element of fantasy to hold a child’s attention,” he says. |

"The charm and whimsy apparent in so many of Hatsuyama’s prints clearly relate to his work as a children’s illustrator. His use of color, which is quite distinctive, may well relate to his early experiences in a dye shop."1

| 日本童画家協会(1927年~1943年ころまで) In 1927 Hatsuyama (top center) helped organize the Nihon Dogaka Kyokai (Japan Association of Illustrators for Children) as part of an effort to achieve artistic quality in illustrations for children, along with fellow artists Takei Takeo 武井武雄 (1894-1982), Kawakami Shirou 川上四郎 (1889 - 1983), Okamoto Kiichi 岡本帰一 (1888-1930), Fukazawa Shouzou 深沢省三 (1899 - 1992), Murayama Tomoyoshi 村山知義 (1901-1977) and Shimizu Yoshio 清水良雄 (1891-1954). Source: Irufu Doga Museum |

Recent Exhibitions

Source: Chihiro Art Museum website http://www.chihiro.jp/english/info/exb_info_a.htmChihiro Art Museum Azumino, Japan 2008 "Celebrating the 110th Anniversary of the Birth of Shigeru Hatsuyama."

Literature

Hatsuyama Shigeru Eien no Modanisuto (Shigeru Hatsuyama, Eternal Modernist), Yuko Takesako, Kawade Shobou, 2007Hatsuyama Shigeru sakuhin shu (The works of Hatsuyama Shigeru), Kodansha, 1973