Bijin and Cherry Tree,

c. 1915-early 1930s

IHL Cat. #1794

Bijin at the Seashore (untitled)

c. 1915-early 1930s

IHL Cat. #2386

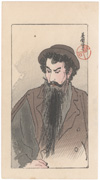

Hirezaki Eihō is primarily known as a creator of illustrations, both sashi-e 挿絵 and kuchi-e 口絵, for newspapers, magazines and novels. In addition to Eihō 英朋 he used the artist names [gō] Kendō 絢堂 and Shinji 晋司.

Sashi-e are black and white illustrations inserted into books, magazines and newspapers to illustrate certain scenes to readers. Kuchi-e are colored frontispieces (separately printed) inserted in the beginning of books and magazines which may illustrate a main theme of the story.

The end of the Meiji era saw an upsurge in the printed word, with a massive output of magazines and novels, many aimed at a new working-class female audience. To help ease the transition to literacy, these were often lavishly illustrated with kuchi-e (literally, “mouth pictures”), colorful foldout illustrations hand-printed in the tradition of ukiyo-e style and later in the Taishō era machine printed by rotary offset press.

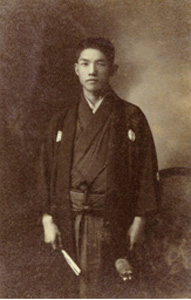

Born Hirezaki Tarō in the Kyōbashi district of Tokyo on March 29, 1880 he completed his compulsory education (likely 4 years of elementary school) at Tsukiji Meikyō Gakkō, a mission school. His father was a metal craftsman from Kyoto who either died, or left the family, when Hirezaki was quite young. Eihō lost his parents at a young age, and later had to support both his grandparents and his own family of seven children. Merritt and Yamada state that “As a young man Eihō suffered from beriberi and pleurisy, which were apparently related to overwork…” Other than these few facts, little seems to have been recorded in English about Hirezaki’s early life.2

Hirezaki studied ukiyo-e with one of Tsukioka Yoshitoshi's (1839-1892) most famous students Migita Toshihide (1863-1925) starting in 1897,for an unknown duration, and would go on to study Maruyama-Shijō painting in1904 with the nihonga painter Kawabata Gyokushō (1842-1913).3 Hirezaki may also have had some earlier instruction as it is reported that he started exhibiting his paintings as early 1898.

From 1901until 1923 Eihō worked for the newspaper Asahi Shimbun as an illustrator, creating action sketches of sumō matches which brought him a measure of fame, as would his designs of kuchi-e created while working in the art department of Tokyo publisher Shun’yōdō from 1902 until 1913, and for the popular culture magazines Shin shōsetsu (published by Shun’yōdō), Bungei kurabu (Literary Club), starting in 1907, Fujokai (Women’s World), starting in 1910 and Goraku sekai (World of Amusement), starting in 1913. He also illustrated school books, drawing sashi-e, for the Ministry of Education and illustrated the classic children’s book Grandfather Cherry Blossom 花咲爺 , translated and released with Eihō’s original drawings by Kodansha International in 1993.

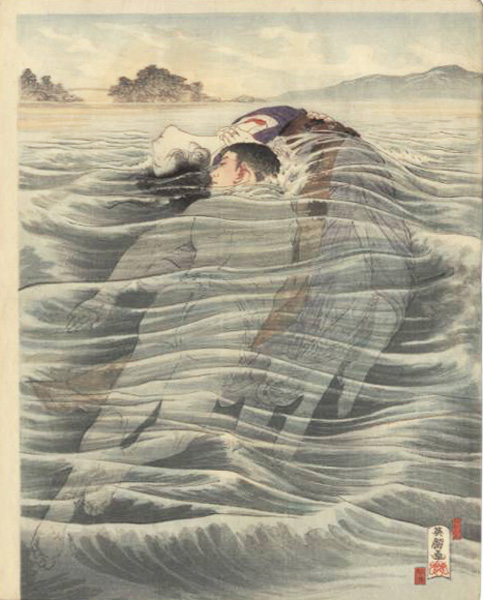

One of Eihō’s best known illustrations (shown below) was for the 1905 novel Zoko Fūryūsen (Elegant Line) by Izumi Kyōka (1873-1939), described as showing “the artist’s skillful use of shading…employed to create the movement and transparency of waves.”4 He was one of eight artists chosen to design the eight prints appearing in the “pocket edition,”issued in 1920/1921 by Shun’yōdō, of, perhaps, the most famous novel of the late-Meiji period, The Gold Demon, by Ozaki Kōyō (1868-1903). (See this collection’s print The Character Araō Jōsuke from the novel The Gold Demon.)

In 1901, he co-founded the Ugōkai (Cormorant Society) with Kaburaki Kiyokata (1878-1972), Yamanaka Kodō (1869-1945) and others in order to promote the work of artists left out of official exhibitions and as “a study group for developing fresh ideas for genre painting following in the ukiyo-e tradition”5 He exhibited with them until their dissolution in 1912. He was also a member of Bungei kakushin kai (Literature and Art Reformation Society), founded by the writer, critic and editor Gotō Chūgai in “objection to the (naturalistic) notion of writing about reality without the guidance of ideals.”6

In the early 1920s he designed the shin hanga style print titled Cherry Blossoms, April (Shigatsu, Sakura) for the series of twelve prints, one for each month, by twelve artists, New Ukiyo-e Beauties (Shin ukiyo-e bijin awase) published by Murakami.

His friend, the artist Yamanaka Kodō (1869-1945), wrote that ”Eihō was a man of strict morals, a sympathetic listener, and conscientious about meeting deadlines.” Influenced by the novelist Izuma Kyōka, “he enjoyed telling ghost stories and practicing divination.”

In 2010, the Yayoi Museum presented an exhibition of 350 pieces of Eihō’s work in an effort to re-introduce this previously overlooked artist who Nanako Yamada refers to as “a superbly-skilled artist” whose drawings of women had “an aura of fascination and enchantment.”

Sample Artist Signature and Seals

Hirazaki Eiho 130th Anniversary Exhibition

(article by Marius Gombrich appearing in the online edition of The Japan Times)

http://www.japantimes.co.jp/culture/2010/02/26/arts/hirazaki-eiho-130th-anniversary-exhibition/#.WWfaBIjyuUkNext door to the Yumeji Takehisa Museum, and serving as its companion in terms of period and spirit, is the Yayoi Museum. Its third floor houses a permanent exhibition of works by the little-known Taisho (1912-26) and Showa (1926-89) era illustrator Kasho Takabatake, but the lower floors feature special exhibitions, such as the current “130th Anniversary Exhibition of Hirezaki Eiho,” which includes 350 artworks and items associated with the artist whose career covered three eras, from Meiji (1868-1912) to Showa.

Born in 1880, Eiho studied under the ukiyo-e artist Toshihide Migita, but later moved into book, magazine and newspaper illustration, where he was something of a pioneer. The end of the Meiji era saw an upsurge in the printed word, with a massive output of magazines and novels, many aimed at a new working-class female audience. To help ease the transition to literacy, these were often lavishly illustrated with kuchi-e (literally, “mouth pictures”), colorful foldout illustrations hand-printed in the tradition of ukiyo-e style.

Eiho became famous for his sketches of sumo wrestlers in action that appeared in the Asahi Shimbun newspaper, but far more satisfying are his elaborate kuchi-e, such as the one produced for the 1905 publication of “Zoku Furyusen” (“The Line of Elegance”), a novel by Kyoka Izumi. This shows the artist’s skillful use of shading, here employed to create the movement and transparency of waves. After his death in 1968, he was largely forgotten, but recently there have been moves to reappraise his work.

晉司 Shinshi seal |  ?堂 unread seal |  unread seal |  ?堂 unread seal |  英朋 Eihō 英司 Eishi seal |  unread seal |

1 Dates of birth-death given as 1881-1970 in Woodblock Kuchi-e Prints: Reflections of Meiji Culture, Helen Merritt and Nanako Yamada, University of Hawaii Press, 2000

2 WikipediaJapan does have more information on his early life and can be found at https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E9%B0%AD%E5%B4%8E%E8%8B%B1%E6%9C%8B]

3 Kuchi-e artists often created scenes or details in techniques derived from the Maruyama-Shijō or nanga styles. The Maruyama-Shijō [naturalistic] style was begun by Maruyama Ōkyo (1733-1795), who combined traditional ink painting and touches of color with careful drawing from direct observation. After Matsumura Goshun (1752-1811) of the Shijō section of Kyoto developed the style further, it became known as the Maruyam-Shijō style. [Woodblock Kuchi-e Prints: Reflections of Meiji Culture, Helen Merritt and Nanako Yamada, University of Hawaii Press, 2000, p. 21.]

4 Article by Marius Gombric announcing Eihō exhibition appearing in the on line edition of The JapanTimes http://www.japantimes.co.jp/culture/2010/02/26/arts/hirazaki-eiho-130th-anniversary-exhibition/

5 "Stepmother, Stepson: Novel by Yanagawa Shun’yō, Kuchi-e by Hirezaki Eihō, published by Kanao Bun’endō” appearing in Andon, Volume 71, Journal of the Society for Japanese Arts, p. 25-31.

6 The Similitude of Blossoms: A Critical Biography of Izumi Kyōka (1873-1939), Japanese Novelist and Playwright, Charles Shirō Inouye, Harvard University Press, 1998, p. 238.