Prints in Collection

Album of Beauties by Kiyokata, 1914

Dormitory in Spring Rain

IHL Cat. #1815

Deep Blue Sky

IHL Cat. #1816

Nozakimura

IHL Cat. #1819

Early Summer Rain

IHL Cat. #1820Afternoon Sea

IHL Cat. #1821

Hot Spring in Springtime

IHL Cat. #1822

White Wall

IHL Cat. #1823

First Snow

IHL Cat. #1824

Beside the Lake

IHL Cat. #1825

Shimadakuzushi

IHL Cat. #1826

IHL Cat. #1973

Poppy Flower, c. 1975 (orig. 1913)

IHL Cat. #2094

Biographical Data

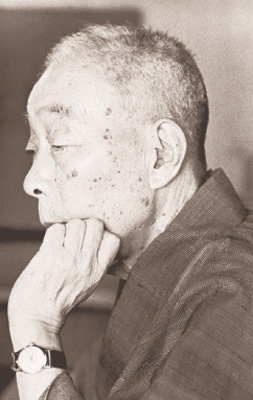

| ProfileKaburaki Kiyokata 鏑木清方 (1878-1972) [also seen transliterated asKaburagi Kiyokata1]

|

1 The British Museum in their biography of Kiyokata notes "A family member has confirmed that the correct reading of the name is Kaburaki."

2 Nihonga Transcending the Past: Japanese-Style Painting, 1868-1968, Ellen P. Conant, The Saint Louis Art Museum, 1995, p. 300.

Bijinga (Pictures of Beautiful Women) - The Artist's Statement

Bijinga belongs to a section of genre painting that has been named Ukiyo-e… In the past there was a misconception that it was “vulgar” to reproduce fashionable customs and manners, and the artists who depicted contemporary fashions were limited to Ukiyo-e … Even someone with an afflicted mind or who nurses discontent cannot help but unload his hear of stone before beautiful flowers and charming beauties. The fact that everyone is attracted is the merit of the beauties, in other words, that is the merit of bijinga. This universality has a conventional side,and I cannot deny the fact that this conventionality sometimes descends into vulgarity. As a result Ukiyo-e was looked down upon in olden times. Attractive beauty but not indecency, sweetness is fine but not low-class: the person who paints bijinga has to keep this balance very much in mind.

- Kaburaki Kiyokata

Kiyokata showed this work [left], one of his masterpieces, at the government-sponsored Imperial Academy Art Exhibition (Teiten). He used to say that whenever he felt doubts about his work, he would recover by looking at this painting. The painting is based on life at Kiyokata’s summer home at Kanazawa Hakkei (now Kanazawa-ku in Yokohama). It was his habit to take walks in the company of his oldest daughter early in the morning when the moon was still visible in the sky. A lotus blooms among the expanse of paddy fields behind the figure of Kiyokata’s daughter.* * Website of the Kamakura Arts Foundation http://www.kamakura-arts.or.jp/kaburaki/english/about/building.html

Sources: Nihonga Transcending the Past: Japanese-Style Painting, 1868-1968, Ellen P. Conant, The Saint Louis Art Museum, 1995; "Kaburagi Kiyokata: Painter of Beauties," by Takeda Michitarō appearing in Japan Quarterly, July 1, 1958; Printed to Perfection – Twentieth-century Japanese Prints from the Robert O. Muller Collection, Joan B. Merviss, et. al., Smithsonian Gallery and Hotei Publishing, 2004 ; The Pupils of Kaburaki Kiyokata: New Ukiyo-e from the Greater Taisho Period, Maureen de Vries, Chirs Uhlenbeck and Elise Wessels, Nihon no Hanga, 2012; Modern Japanese Woodblock Prints - The Early Years, Helen Merritt, University of Hawaii Press, 1998; Guide to Modern Japanese Woodblock Prints: 1900-1975, Helen Merritt, University of Hawaii Press, 1992; Woodblock Kuchi-e Prints: Reflections of Meiji Culture, Helen Merritt and Nanako Yamada, University of Hawaii Press, 2000; website of the Kaburaki Kiyokata Memorial Art Museum http://www.kamakura-arts.or.jp/kaburaki/english/about/index.html; Wikipedia https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kiyokata_Kaburagi; website of the Kamakura Arts Foundation http://www.kamakura-arts.or.jp/kaburaki/

Kaburaki Kiyokata was born Kaburaki Ken’ichi 健一 on August 31, 1878 in Kanda, Tokyo. He grew up in an affluent and literary household, his father Jōno Saigiku Denpei (1832-1902) being a famous popular novelist under his literary name, Sansantei Arindo, and a founder of two newspapers, the Tokyo nichinichi shinbun in 1872 (Tokyo’s first daily newspaper) and the Yamato shinbun in 1886. His mother was Kaburaki Fumi. His family were fans of kabuki and acquainted with a range of popular figures such as the ukiyo-e print artists Utagawa Hiroshige III (1842-1894), Utagawa (Ochiai) Yoshiiku (1833-1904) and Tsukioka Yoshitoshi (1839-1892), the lacquer craftsman and painter Shibata Zeshin (1807-1891) and the rakugo performer San’yūtei Enchō (1829-1900).

Kiyokata, after completing primary school, entered the Tokyo English School (Tokyo Eigo Gakkō). His first drawing lessons at the age of eight or nine are reported to have come from the second son of Shibata Zeshin (1807-1891), Shibata Shin’ya (n.d.), but his more formal training began in 1891, when at the age of thirteen he became a pupil of the prolific print artist and illustrator Mizuno Toshikata (1866-1908), a student of the famous late-Meiji era ukiyo-e artist Tsukioka Yoshitoshi (1839-1892), who worked part time as an illustrator for his father’s paper. His time with Toshikata gave him a firm grounding in ukiyo-e and the artistic traditions of the Utagawa School and in 1893 he took the gō (artist name) “Kiyokata” which he was to use throughout his long career.1

In 1893/1894, due to financial difficulties associated with the management of the Yamato shinbun resulting in his family losing everything, including their house, Kiyokata with his mother and grandmother were reduced to living with relatives or in boarding houses.2 To help support his family he drew designs for summer kimono and went to work for the Yamato creating illustrations. Through the remainder of the decade he focused on creating illustrations for serial novels and improving his skills as a painter. Towards the end of the 1890s, he became an assistant illustrator to the artist Kajita Hanko (1870-1917) at the Yomiuri shinbun, who he credits with opening "a new world" for him. 1b He learned everything he could from Hanko on drawing bijinga.

At the age of eighteen, he received his first student, Kadoi Kikusui (1886-1976), who would go on to a long career as a nihonga artist. Other students would follow, including many of the artists who would become luminaries in the shin hanga movement, such as Kawase Hasui (1883-1957), Itō Shinsui (1898-1972), Kasamatsu Shirō (1898–1991), Kobayakawa Kiyoshi (1897-1948), Terashima Shimei (1892-1975) and Torii Kotondo (1900-1976). In explaining Kiyokata’s success as a teacher, the authors of the catalog The Pupils of Kaburaki Kiyokata largely credit this not to his artistic accomplishments in his early years, but rather to his high profile “as a member of numerous clubs and institutions,”, “his connections in the literary world through newspapers, and his work as an illustrator of novels,” and his “reputation as an excellent teacher,” going on to say that “his vigorous defense of his style as Shin ukiyo-e gave his pupils a direction and identity for their art.”3 In 1917 he gave up teaching to devote himself to the creation of "a new bijinga with subjects from the modern world."4

Bijin and Rooster, 1902 Kuchi-e for the novel Sanmai tsuzuki by Izumi Kyōka 『三枚続』(泉鏡花著)口絵 明治35(1902)年 | In 1901, eager to expand his career as an illustrator, he met the author Izumi Kyōka (1873-1939), who commissioned him to illustrate his novel Triptych ("Sanmai tsuzuki") and with whom he would continue to collaborate, forming a close friendship. It was also in 1901 that Kiyokata founded the influential Cormorant Society (Ugōkai 烏合会) together with other illustrators such as Ikeda Terukata (1883-1921), Hirezaki Eihō (1880-1968) and Yamanaka Kodō (1869-1945), whose purpose was to revitalize the bijinga genre and elevate the status of illustrators who were looked down upon by the formal art establishment. Although he was successful as an illustrator and would continue to create illustrations for novels and magazines, such as Kabuki and Bungei kurabu, Kiyokata turned his focus to nihonga-style painting at about this time, creating works depicting bijinga and the life of the common people. His nihonga are praised by modern critics and art historians as going “beyond simple representations of beautiful ladies … to evoke a feeling for the entire age in which the subject is set”5 and as “giving his figures a penetrating sense of interiority.”6 |

In 1902, to allow himself more time for painting, he resigned his job at the Yomiuri shinbun. In 1903 he married Rsuzuki Teru, a younger sister of a fellow Ugōkai member.

Submitting paintings to the Bunten, the official government exhibition organized by the Imperial Academy of Fine Arts, starting in 1907, he did not have a painting accepted until the Bunten's Third Exhibition in 1909, when his diptych Mirrors won an award. He would go on to win several Bunten awards, including first prize in 1915 for his work Murasame 村雨. In 1917 he would be appointed as a judge at the first Teiten, the Bunten’s successor, further solidifying his reputation as a painter.

In 1917, together with the novelist Taguchi Kikutei (1875-1943) (Kikutei being the nom de plume of Taguchi Kyōjirō) and painters Hirafuku Hyakusui (1844-1890), Matsuoka Eikyū (1881-1938), Yoshikawa Reika (1875-1929) and Yūki Somei (1875-19570, he helped found Kinreisha (Golden Bell Society), a nihonga association training promising young artists, including Kawase Hasui (1883-1957). Kinreisha was one of many attempts by artists to find a way out of the impasse traditional painting had reached. "Kiyokata and his friends wished, in short, to bring about a renaissance in the field of Japanese painting."7 Taguchi, the "brainchild" of Kinreisha, was the founder of the Japan Art Academy (Nihon Bijutsu Gakuin), one of Japan's first correspondence art schools, established in 1913. Kiyokata was one of the teachers hired for the school and the school was to publish Kiyokata's album of twelve prints titled Kiyokata bijin gafu, further discussed on this site's pages displaying the prints from that album, in 1914.

When the publisher Watanabe Shōzaburō started an export woodblock print business, he needed many talented artists to make print designs appealing to western audiences. Kaburaki's group became a recruiting center for Watanabe. Kaburaki organized exhibitions with works of his students and introduced his best students to Watanabe. Next to Watanabe himself, it was probably Kiyokata Kaburaki, who had the greatest influence on the development and promotion of the shin hanga movement. Not only Kawase Hasui, but also Itō Shinsui, Kasamatsu Shirō, Yamakawa Shūhō (1898-1944), and Torii Kotondo and Terashima Shimei (1892-1975) were trained by Kaburaki and then introduced to Watanabe.

When Kaburaki had reached his late 40s, he was a well-established and highly respected artist. In 1927 he was to paint his largest and most important work, Tsukiji Akashi-chō,8 called a "monument to the modern bijinga" and awarded the Grand Prize by the Imperial Academy of Art.9 This painting was also reproduced as a woodblock print, becoming his most well-known painting to be reproduced in woodblock.

In 1929 he became a member of the Imperial Fine Art Academy (Teikoku Bijutsuin) and his 1930 portrait of rakugo actor San'yūtei Enchō, shown below, was registered as an Important Cultural Property (ICP) by the Agency for Cultural Affairs in 2003.

Portrait of San'yūtei Enchō, 1930

三遊亭円朝像

color on silk, hanging scroll, 54 1/2 x 30 in. (138.5×76.0 cm)

In 1934 a collection of his essays was published and ten more volumes followed in the next decade, including his celebrated autobiographical work, Records of My Life (Koshikata no ki こしかたの記), in 1941. “This shift to personal memoirs may have been his way of avoiding serious involvement in the nation’s war effort, which he privately criticized.”10 His opinions about the war must have been quite private, as in 1938 he was appointed to the Art Committee of the Imperial Household and he received the official position of court painter in 1944. In 1946, he was asked to be one of the judges for the first post-war Nitten Exhibition. In 1954, he received the Order of Culture.

After losing his Tokyo home to the firebombing in World War II, he relocated to Kamakura, Kanagawa Prefecture, where he lived until his death, passing away at the age of 93. His grave is at the Yanaka Cemetery in Tokyo. His house in Kamakura has been transformed into the Kaburaki Kiyokata Memorial Museum, displaying many of his works, and preserving his studio.

KIYOKATA'S WOODBLOCK PRINTS

Kiyokata's contributions of original designs for woodblock were mainly in the form of kuchi-e (frontispieces and colored illustrations for novels and magazines). Single-sheet woodblock prints bearing his signature and or seal, are mostly after his paintings, although he did create original designs for a portfolio of prints in 1913 titled Kiyokata's Picture Book of Beauties, that contained four woodblock prints (see examples below, along with the two prints in this collection IHL Cat. #s 1815 and 1816, shown above) and eight lithographs. Merritt notes that single-sheet prints [were] published by Satō Shōtarō in 1909 and that publishers “continued to make moku-hanga [fukusei hanga or reproductive prints] from his paintings.”11 Among the publishers who issued woodblock prints after the paintings of Kiyokata are Kyoto hanga- in, Adachi Printing company, Nakai, Baba Nobuhiko and Nihon bijutsu gakuin (Japan Art Academy). It is unknown how much involvement Kiyokata had with the production of woodblock prints during his lifetime that were made after his paintings.The collector Robert Vergez writing in the journal Ukiyo-e Geigetsu12 notes the following:

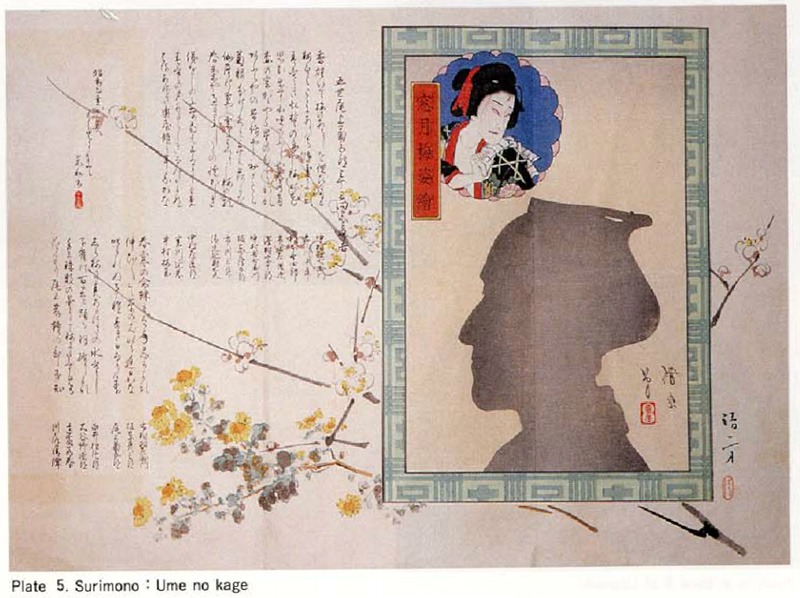

Stylistically, the print oeuvre of Kiyokata followed the same path as that of his paintings. However, he used the medium of the woodblock sporadically, and unlike his illustrious predecessors, he never tried to create single sheets per se, much less prints in sets or series. He is known to have made some surimono [see below] in the 1930s, and to have contributed many kuchi-e to the magazine Bungei club [Bungei kurabu].

Apart from four small woodcuts executed in 1914 for Kiyokata bijin gafu [see below], [his woodblock prints] are mostly kuchi-e....

It appears that he designed woodblock prints, mainly kuchi-e, between around 1900 and 1920.

17 3/8 x 25 5/8 in. (44.2 x 57.4 cm)

as an insert for the 50th Year Commemoration of Jiji Shinpō

明治十五年代美人風俗 薄雪

時事新報 創刊五十年記念附録

Usuyuki, Meiji jūgonen dai bijin fūzoku

Jiji Shinpō sōkan gojūnen kinen furoku

signed: Narau Taiso-o, Kiyokata

20 1/16 x 14 3/8 in. (51 x 36.5 cm)

* It is noted in The Pupils of Kaburaki Kiyokata that "at least two later editions exist, including a poorly printed kuchi-e."

濱町河岸の秋 清方美人画譜published by Nihon Bijutsu gakuin (Japan Art Academy)

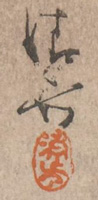

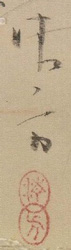

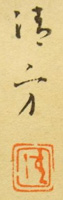

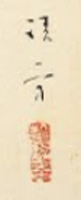

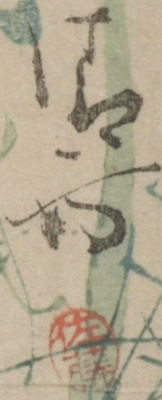

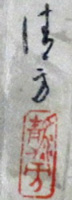

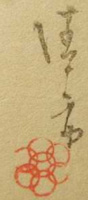

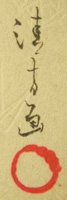

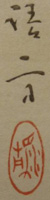

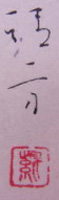

A Sampling of Signatures and Seals of the Artist

清方 Kiyokata |  清方 / 清方 Kiyokata with Kiyokata seal |  清方 / 清方 清方 / 清方Kiyokata with Kiyokata seal |  清方 / 清方 Kiyokata with Kiyokata seal |  清方 / 清 清方 / 清Kiyokata with Kiyo seal |  清方 / 清 清方 / 清Kiyokata with Kiyo seal |

清方 / unread 清方 / unreadKiyokata with unread seal | Kiyokata with unread seal |  清方 / unread 清方 / unreadKiyokata with unread seal |  清方 / ?清方 清方 / ?清方Kiyokata with unread seal |  清方 / 清方 清方 / 清方Kiyokata with Kiokata seal |  清方 / unread Kiyokata with unread seal |

清方 / 清方 / Kiyokata with seal in shape of 7 overlapping circles |  清方画 / 年玉印 清方画 / 年玉印Kiyokata ga with Toshidama seal |  清方 / unread 清方 / unreadKiyokata with unread seal |  清方 / 紫 清方 / 紫Kiyokata with shi seal |  清方 / unread 清方 / unreadKiyokata with unread seal |  清 / Kiyo? 清 / Kiyo?Kiyokata with unread seal |

清方 /清方 Kiyokata with Kiyokata seal |  清方 / 清方 Kiyokata with Kiyokata seal |  きよかた? / unread |  清方 / 紫 Kiyokata with shi seal |

1 According to Woodblock Kuchi-e Prints: Reflections of Meiji Culture, Helen Merritt and Nanako Yamada, University of Hawaii Press, 2000, p. 198 Other gō used by the artist include “Ken” 健, Shōgai 象外, and Ajisai no ya あざさゐのや and 紫陽花舎. However, I have not seen any works with these artist names inscribed on them.

2"Kaburagi Kiyokata: Painter of Beauties," Takeda, Michitaro, appearing in Japan Quarterly, Tokyo, Vol. 5, Iss. 3, (Jul 1, 1958): 317.

1b ibid. p. 318.

3 The Pupils of Kaburaki Kiyokata: New Ukiyo-e from the Greater Taisho Period, Maureen de Vries, Chris Uhlenbeck and Elise Wessels, Nihon no Hanga, 2012, p. 18-19.

3 The Pupils of Kaburaki Kiyokata: New Ukiyo-e from the Greater Taisho Period, Maureen de Vries, Chris Uhlenbeck and Elise Wessels, Nihon no Hanga, 2012, p. 18-19.

4 op. cit., "Painter of Beauties", p. 321.

5 Biographical Dictionary of Japanese Art, Yutaka Tazawa, Kodansha International, Ltd. in collaboration with the International Society for Educational Information, Inc., 1981, p. 112.

6 Nihonga Transcending the Past: Japanese-Style Painting, 1868-1968, Ellen P. Conant, The Saint Louis Art Museum, 1995, p. 109

7 "Kaburagi Kiyokata: Painter of Beauties," by Takeda Michitarō appearing in Japan Quarterly, July 1, 1958, p. 321.

8 Often seen translated as "Woman of Tsukiji". The Museum of Fine Arts, Boston shows the English title for the print as "A Beautiful Woman at Tsukiji Akashi-chô, Kawagishi"

9 op. cit., "Painter of Beauties", p. 322.10 op. cit., "Nihonga Transcending the Past", p. 301.

11 Guide to Modern Japanese Woodblock Prints: 1900-1975, Helen Merritt, University of Hawaii Press, 1992, p. 51.

12 "Kuchi-e by Kaburagi Kiyokata", Robert Vergez appearing in Ukiyo-e Geijutsu, Issue 100, Japan Ukiyo-e Society, 1991.last revision:

12/12/2018