About This Print

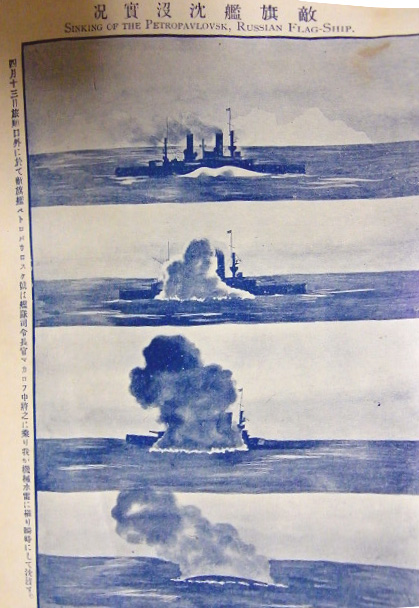

Source: In Battle's Light: Woodblock Prints of Japan's Early Modern Wars, Elizabeth de Sabato Swinton, Worcester Art Museum, 1991, p. 124On the night of April 12, 1904 the Japanese laid a minefield and stood offshore to tempt the Russians out of port and onto it. They had paralyzed and bottled up the Russian Port Arthur squadron since February 8. The great Russian Admiral Makarov managed to leave port and gave pursuit, but on his way back to port, as both the English and Japanese captions relate:

The Japanese navy lay unchallenged off of Port Arthur.

The Japanese admiration of the Russian admiral is apparent in his defiant posture as he goes down with his ship. By emphasizing Makarov's heroism, the artist glorifies Japan as the victor over so formidable an enemy and as a power worthy of respect.

Source: Japan at the Dawn of the Modern Age – Woodblock Prints from the Meiji Era, Louise E. Virgin, Donald Keene, et. al., MFA Publications, 2001, p. 121

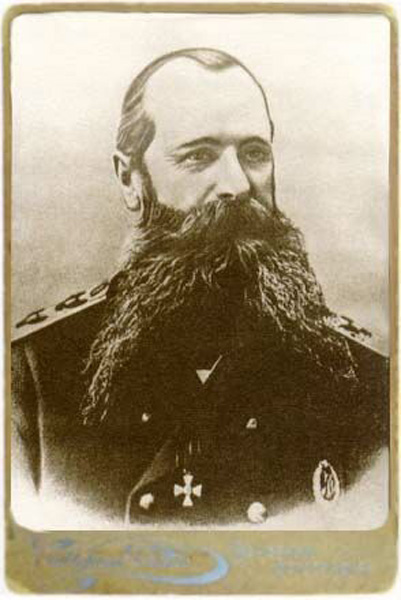

A small number of Russo-Japanese War prints portray Russian officers as gallant and formidable adversaries worthy of respect. The energetic commander Vice Admiral Stephan Ossipovitch Makarov was one such adversary, depicted in the print on the deck of the sinking Petropavlosk.

Detail from print |  Undated photo of Admiral Makarov |

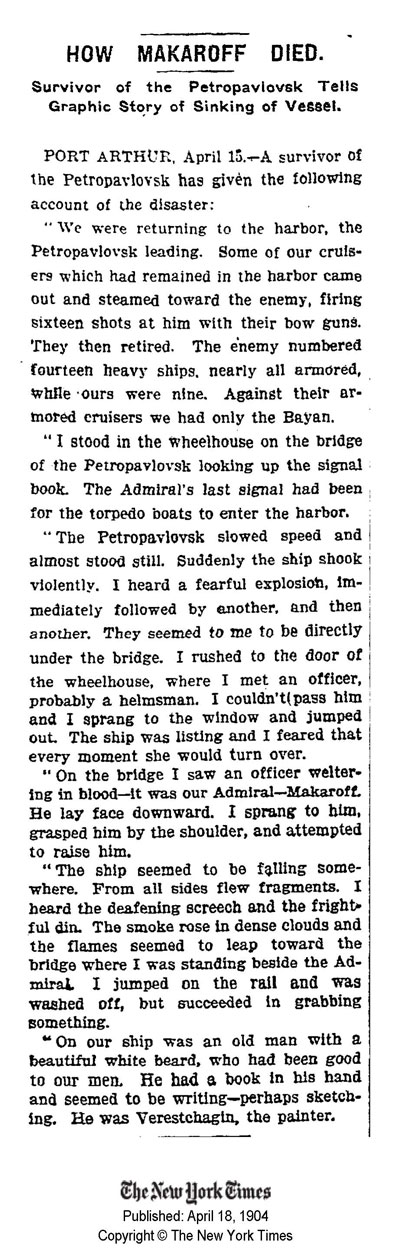

| click on article to enlarge |

| Sinking of the Russian Flagship from unidentified Japanese magazine | How Makaroff Died - New York Times, April 18, 1904 |

Description of the Sinking

Source: Official History of the Russian-Japanese War: A Vivid Panorama of Land and Naval Battles, J. Martin Miller, 1905, p. 325-326

On the morning of April 13, a few Japanese (ships) were seen approaching Port Arthur. Seeing that he did not have a superior force to engage, Admiral Makaroff signaled all the ships of his fleet to follow him to sea and went out to do battle. Before the Japanese fleet was reached, re-enforcements for Admiral Togo appeared on the horizon, swelling the attacking force to thirty ships, big and little. There was no chance for the Russian fleet to win against such odds, and Makaroff signaled a retreat.

No Chance to Escape

The squadron was entering the roadstead when the Petropavlovsk either touched a mine or was struck by a torpedo shot from a submarine boat. A huge hole was blown in the starboard side of the ship, near the middle, and she immediately turned turtle and sank bottom up in a few minutes. The crew was at the fighting stations, and the Russians, penned up below the decks and in the turrets, had no chance to escape, for the disaster was over in a minute.

Immediately after the explosion the sailors were signaled to flood some of the compartments on the port side to throw the ship on an even keel, but they had no time even to begin this work. It is believed that Admiral Makaroff was in the conning tower, from which there was no chance to escape. With the Grand Duke Cyril on the bridge of the ship, were Captain N. Jakovleff and two other officers, and all were saved. It was claimed by many that a submarine torpedo boat struck the blow that sank the Russian flagship, that unseen and unsuspected, the “assassin of the sea” crept up under the ironclad and stabbed it in its vitals. In two and one-half minutes a $5,000,000 armored vessel, the most powerful sea-fighter in the Czar’s navy, lay in scrap-iron at the bottom of the sea, with the commander-in-chief and his staff and 800 men wiped out.

Admiral Togo's Report Following the Death of Admiral Makaroff

Source: The Russo Japanese War Research Society website http://www.russojapanesewar.com/togo-aar2.html

Admiral Togo's official report following the death of Admiral Makaroff is as follows:

On the 11th our combined fleet commenced, as previously planned, the eighth attack upon Port Arthur. The fourth and fifth destroyer flotillas, the fourteenth torpedo flotilla, and the Koryo Maru reached the mouth of Port Arthur at midnight of the 12th, and effected the laying of mines at several points outside the port, defying the enemy's searchlight.

The second destroyer flotilla discovered, at dawn of the 13th, one Russian destroyer trying to enter the harbor, and, after ten minutes' attack, sank her.

Another Russian destroyer was discovered coming from the direction of Liau-tie-shan. We attacked her, but she managed to flee into the harbor.

There were no casualties on our side, except two seamen in Ikazuchi slightly wounded. There was no time to rescue the enemy's drowning crew, as the Bayan approached.

The third fleet reached outside of Port Arthur at 8 a.m., when the Bayan came out and opened fire. Immediately the Novik, Askold, Diana, Petropavlovsk, Pobieda, and Poltava came out and made offensive attack upon us.

Our third fleet, tardily answering and gradually retiring, enticed the enemy fifteen miles southeast of the port, when our first fleet, being informed through wireless telegraphy from the third fleet, suddenly appeared before the enemy and attacked them.

While the enemy was trying to regain the port, a battleship of the Petropavlovsk type struck mines laid by us in the previous evening, and sank at 10:32 a.m.

Another ship was observed to have lost freedom of movement, but the confusion of enemy's ships prevented us from identifying her. They finally managed to regain the port.

Our third fleet suffered no damage.

The enemy's damage was, besides the above mentioned, probably slight also.

Our first fleet did not reach firing distance. Our fleets retired at 1 p.m., prepared for another attack.

On the 14th our fleet resailed towards Port Arthur. The second, the fourth, and the fifth destroyer flotillas and the ninth torpedo flotilla joined at 3 a.m., and the third fleet at 7a.m. No enemy's ship was seen outside the port.

Our first fleet arrived there at 9 a.m., and, discovering three mines laid by the enemy, destroyed them all.

The Kasuga and the Nisshin were dispatched to the west of Liau-tie-shan. They made an indirect bombardment for two hours, this being their first action. The new forts at Liau-tie-shan were finally silenced.

Our forces retired at 1:30 p.m.

Togo

This installation features more than 30 loans from two remarkably rich local resources, the Lavenberg Collection of Japanese Prints, and the Lee & Mary Jean Michels Collection. It was co-curated by Professors Akiko Walley (History of Art and Architecture) and Glynne Walley (East Asian Languages and Literatures) and JSMA Chief Curator Anne Rose Kitagawa. QR codes on selected labels allow visitors to access translations and explanations of the complex wordplay, imagery, and cultural context of these fascinating objects.

IKEDATerukata (池田輝方,1883-1921)

Japanese;Meiji period, April 1904

A Great Victory for the Great Japanese ImperialNavy, Hurrah! (Dai-Nihon teikoku kaigundai-shōri banzai)

Ukiyo-e woodblock-printed vertical ōban triptych; ink and color on paper

TheLavenberg Collection of Japanese Prints, IHL.0102

This installation features more than 30 loans from two remarkably rich local resources, the Lavenberg Collection of Japanese Prints, and the Lee & Mary Jean Michels Collection. It was co-curated by Professors Akiko Walley (History of Art and Architecture) and Glynne Walley (East Asian Languages and Literatures) and JSMA Chief Curator Anne Rose Kitagawa. QR codes on selected labels allow visitors to access translations and explanations of the complex wordplay, imagery, and cultural context of these fascinating objects.

IKEDATerukata (池田輝方,1883-1921)

Japanese;Meiji period, April 1904

A Great Victory for the Great Japanese ImperialNavy, Hurrah! (Dai-Nihon teikoku kaigundai-shōri banzai)

Ukiyo-e woodblock-printed vertical ōban triptych; ink and color on paper

TheLavenberg Collection of Japanese Prints, IHL.0102

In February of 1904, a war broke out betweenJapan and Russia over the hegemony of Manchuria and the Koreanpeninsula. The progress of the war that lasted until September of the followingyear was tracked closely by the Western imperial nations as the first modernbattle of East vs. West. As it was during the first Sino-Japanese War (1894-95)a decade before, woodblock prints played a key role in aggrandizing Japan’sRusso-Japanese War (1904-05) victories. However, unlike the previous conflict,the fact that this war was being fought against a Western power had asignificant impact on the way in the enemy was portrayed even in propagandisticwarfront images.

In Ikeda Terukata’s triptych (displayed above),Admiral Makarov of Petropavlovsk (1849-1904) is presented heroically, standingon the deck of his sinking ship and gazing toward the Japanese battleship inthe distance. Hirose Yoshikuni’s print(below) of a Japanese naval mission that took place in March of 1904, providesan intriguing contrast. It portrays Lieutenant Colonel Hirose Takeo(1868-1904), who lost his life attempting to rescue Chief Petty Officer SuginoMagoshichi on the retired merchant ship Fukuimaru, which was about to be blownup and sunk to trap the Russian Baltic Fleet inside Port Arthur. The masculinephysique, upright posture, strong jaw, and intense gaze of Lieutenant ColonelHirose mirror the heroic figure of the Russian Admiral in Terukata’s print. Inboth cases, what the Japanese print designers marshalled was the Westerniconography of masculinity and heroism.

(Akiko Walley, Maud I. Kerns Associate Professor of JapaneseArt, History of Art andArchitecture)

Print Details

| IHL Catalog | #102 |

| Title or Description | A Great Victory for the Great Japanese Imperial Navy, Hurrah! "Dai-Nihon teikoku kaigun dai-shori banzai" 「大日本帝國海軍大勝利萬歳」 |

| Artist | Ikeda Terukata (1883-1921) |

| Signature |  |

| Seal | Toshiide |

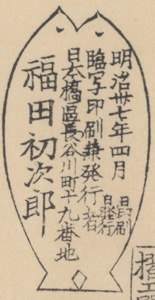

| Publication Date | April 1904 (Meiji 37) |

| Publisher |  address: 日本橋区艮谷川町十九番地 [Marks: pub. ref. 070; seal 30-062] |

| Carver | The third generation Ei (Watanabe Takisaburō, 1876-1947) |

| Printer | Kaino |

| Impression | excellent |

| Colors | excellent |

| Condition | excellent - full size untrimmed sheets |

| Genre | ukiyo-e - senso-e (Russo-Japanese War); Meiji era |

| Miscellaneous | |

| Format | vertical oban triptych |

| H x W Paper | 14 7/8 x 10 in. (37.5 x 25.1 cm) each sheet |

| Literature | In Battle's Light: Woodblock Prints of Japan's Early Modern Wars, Elizabeth de Sabato Swinton, Worcester Art Museum, 1991, p. 124, pl. 74; Japan at the Dawn of the Modern Age – WoodblockPrints from the Meiji Era, Louise E. Virgin, Donald Keene, et. al.,MFA Publications, 2001, p. 121, pl. 69; The Hotei Encyclopedia of Japanese Woodblock Prints, Amy Reigle Newland, Hotei Publishing Company, 2005, Vol. 1, p. 275, fig. 210; Russo-Japanese War Triptychs: Chastising a Powerful Enemy, Elizabeth de Sabato Swinton, article appearing in A Hidden Fire: Russian and Japanese Cultural Encounters, 1868-1926, J. Thomas Rimer, Stanford University Press, 1995, p. 126, fig. 10.9 |

| Collections This Print | Museum of Fine Arts, Boston: Jean S. and Frederic A. Sharf Collection 2000.466a-c |