Source: Woodblock Prints as a Medium of Reportage: The Sino-Japanese and Russo-Japanese Wars, Louise Virgin, article in The Hotei Encyclopedia of Japanese Woodblock Prints, Amy Reigle Newland, Hotei Publishing, 2005, p. 273-276

Citizens collected prints that commemorated and explained events of national interest and importance, including the Sino-Japanese 日清戦争 (1894-95) and Russo-Japanese 日露戦争 (1904-05) Wars. Both wars were the result of Japan's quest to emulate the expansionist policies of Western powers and to prove itself the most modern and powerful military nation in Asia. It did so by asserting its influence in Korea, Taiwan and southern Manchuria.

The rushed print production occasionally gave rise to crude renderings, but talented artists like Yoshu Chikanobu (1838-1912), Watanabe Nobukazu (1872-1944), Ogata Gekko (1859-1920), Taguchi Beisaku (1864-1903), Mizuno Toshikata (1866-1908) and Kobayashi Kiyochika (1847-1915) were motivated to design exceptional works. It is estimated that approximately 3,000 triptychs were published during the Sino-Japanese War. Far fewer and often less inspired works were produced during the Russo-Japanese War when photography was more widely available to chronicle events.

Aiming to convince the public that their scenes were authentic, woodblock print artists tried to imbue their works with a heightened sense of realism, immediacy and dramatic contrasts of light and dark - characteristics appreciated in photographs and Western-style sketches included in imported magazines.

Prints produced during both wars were usually propagandistic in subject matter and emotional overtones. They caricatured the enemy and particularly in the depiction of Chinese soldiers, the images were overtly racist. Prints featured the emperor in charge at his Hiroshima war headquarters, victorious battles and joyful celebrations, camaraderie around the campfire, and the unselfish acts of soldiers and officers. Japanese government censors, however, suppressed the works that revealed the horrors endured by the Japanese military - soldiers suffering from frost-bite during the Sino-Japanese War or the needless death of thousands of soldiers in ill-prepared attempts to conquer Port Arthur during the Russo-Japanese War.

Boom and Bust in Woodblock Print Sales

Source: "Prints of the Sino-Japanese War," Donald Keene appearing in Impressions of the Front: Woodcuts of the Sino-Japanese War, Shunpei Okamoto, Philadelphia Museum of Art, 1983, p. 10.

"In view of the popularity of these war prints, it is surprising that the nishikie, colored woodblock prints, should have died out so soon afterward. It is possible to date this sad occurrence with some precision. A Tokyo newspaper reported in the autumn of 1895, after the war had ended that sales of nishikie had diminished drastically: war prints, of course, were no longer in demand, but even the usual actor prints sold barely two hundred copies each. The print never again was in wide public demand. At the time of the Boxer Rebellion in 19001, publishers commissioned prints, but they sold few copies. Again, during the Russo-Japanese War of 1904-5, many prints were executed but the response of the public was disappointing."

1 See the prints Illustration of the the Army and Navy Protecting the Legations and Japanese Residents and Picture of the Occupation of the Taku Forts and the Hard Fight of Navy Lt. Colonel Hattori for examples of Boxer Rebellion prints in this collection.

Massachusetts Institute of Technology's “Throwing Off Asia” website is at present the most densely illustrated andaccessible treatment of Meiji woodblock prints focusing on theSino-Japanese and Russo-Japanese wars. (The Essays alone include 165prints, of which 111 depict the Sino-Japanese War and 34 theRusso-Japanese War.)

Citizens collected prints that commemorated and explained events of national interest and importance, including the Sino-Japanese 日清戦争 (1894-95) and Russo-Japanese 日露戦争 (1904-05) Wars. Both wars were the result of Japan's quest to emulate the expansionist policies of Western powers and to prove itself the most modern and powerful military nation in Asia. It did so by asserting its influence in Korea, Taiwan and southern Manchuria.

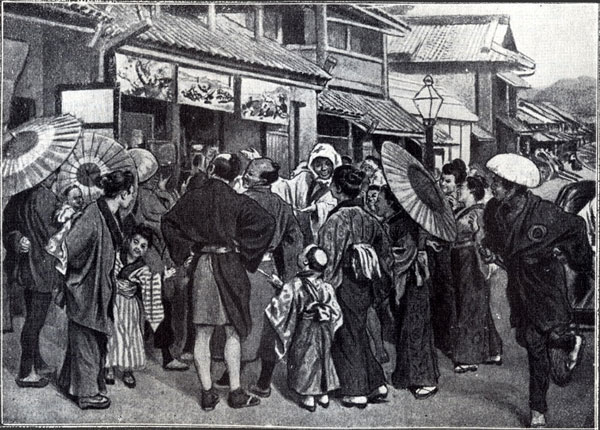

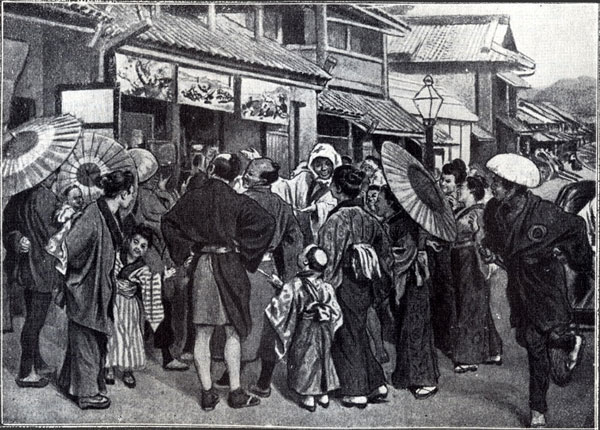

Scene in the Streets of Tokyo When War Prints Were Exhibited.

From Japan's Fight for Freedom (London: Amalgamated Press, 1904), p. 74.

Prints filled a journalistic function but also became a vital propaganda tool during the two wars. The Japanese government and publishers encouraged print artists to illustrate conflicts won with impressive battleships and guns, or portrait series of top military officers. Patriotic citizens were eager to buy images of the latest victories and heroes. Because competition between publishers was fierce, prints were quickly designed, printed and distributed as soon as reports were published in newspapers. Scenes of anticipated events were often conceived in advance and issued in large editions as soon as telegraphic confirmations arrived from the front. Some images were even published before predicted events that never occurred.From Japan's Fight for Freedom (London: Amalgamated Press, 1904), p. 74.

The rushed print production occasionally gave rise to crude renderings, but talented artists like Yoshu Chikanobu (1838-1912), Watanabe Nobukazu (1872-1944), Ogata Gekko (1859-1920), Taguchi Beisaku (1864-1903), Mizuno Toshikata (1866-1908) and Kobayashi Kiyochika (1847-1915) were motivated to design exceptional works. It is estimated that approximately 3,000 triptychs were published during the Sino-Japanese War. Far fewer and often less inspired works were produced during the Russo-Japanese War when photography was more widely available to chronicle events.

Aiming to convince the public that their scenes were authentic, woodblock print artists tried to imbue their works with a heightened sense of realism, immediacy and dramatic contrasts of light and dark - characteristics appreciated in photographs and Western-style sketches included in imported magazines.

Prints produced during both wars were usually propagandistic in subject matter and emotional overtones. They caricatured the enemy and particularly in the depiction of Chinese soldiers, the images were overtly racist. Prints featured the emperor in charge at his Hiroshima war headquarters, victorious battles and joyful celebrations, camaraderie around the campfire, and the unselfish acts of soldiers and officers. Japanese government censors, however, suppressed the works that revealed the horrors endured by the Japanese military - soldiers suffering from frost-bite during the Sino-Japanese War or the needless death of thousands of soldiers in ill-prepared attempts to conquer Port Arthur during the Russo-Japanese War.

Boom and Bust in Woodblock Print Sales

Source: "Prints of the Sino-Japanese War," Donald Keene appearing in Impressions of the Front: Woodcuts of the Sino-Japanese War, Shunpei Okamoto, Philadelphia Museum of Art, 1983, p. 10.

"In view of the popularity of these war prints, it is surprising that the nishikie, colored woodblock prints, should have died out so soon afterward. It is possible to date this sad occurrence with some precision. A Tokyo newspaper reported in the autumn of 1895, after the war had ended that sales of nishikie had diminished drastically: war prints, of course, were no longer in demand, but even the usual actor prints sold barely two hundred copies each. The print never again was in wide public demand. At the time of the Boxer Rebellion in 19001, publishers commissioned prints, but they sold few copies. Again, during the Russo-Japanese War of 1904-5, many prints were executed but the response of the public was disappointing."

1 See the prints Illustration of the the Army and Navy Protecting the Legations and Japanese Residents and Picture of the Occupation of the Taku Forts and the Hard Fight of Navy Lt. Colonel Hattori for examples of Boxer Rebellion prints in this collection.

Links

MIT Visualizing Cultures website "Throwing Off Asia: Woodblock Prints of the Sino-Japanese War (1894-95)" by John Dower http://ocw.mit.edu/ans7870/21f/21f.027/throwing_off_asia_02/toa_essay01.htmlMassachusetts Institute of Technology's “Throwing Off Asia” website is at present the most densely illustrated andaccessible treatment of Meiji woodblock prints focusing on theSino-Japanese and Russo-Japanese wars. (The Essays alone include 165prints, of which 111 depict the Sino-Japanese War and 34 theRusso-Japanese War.)