About This Print

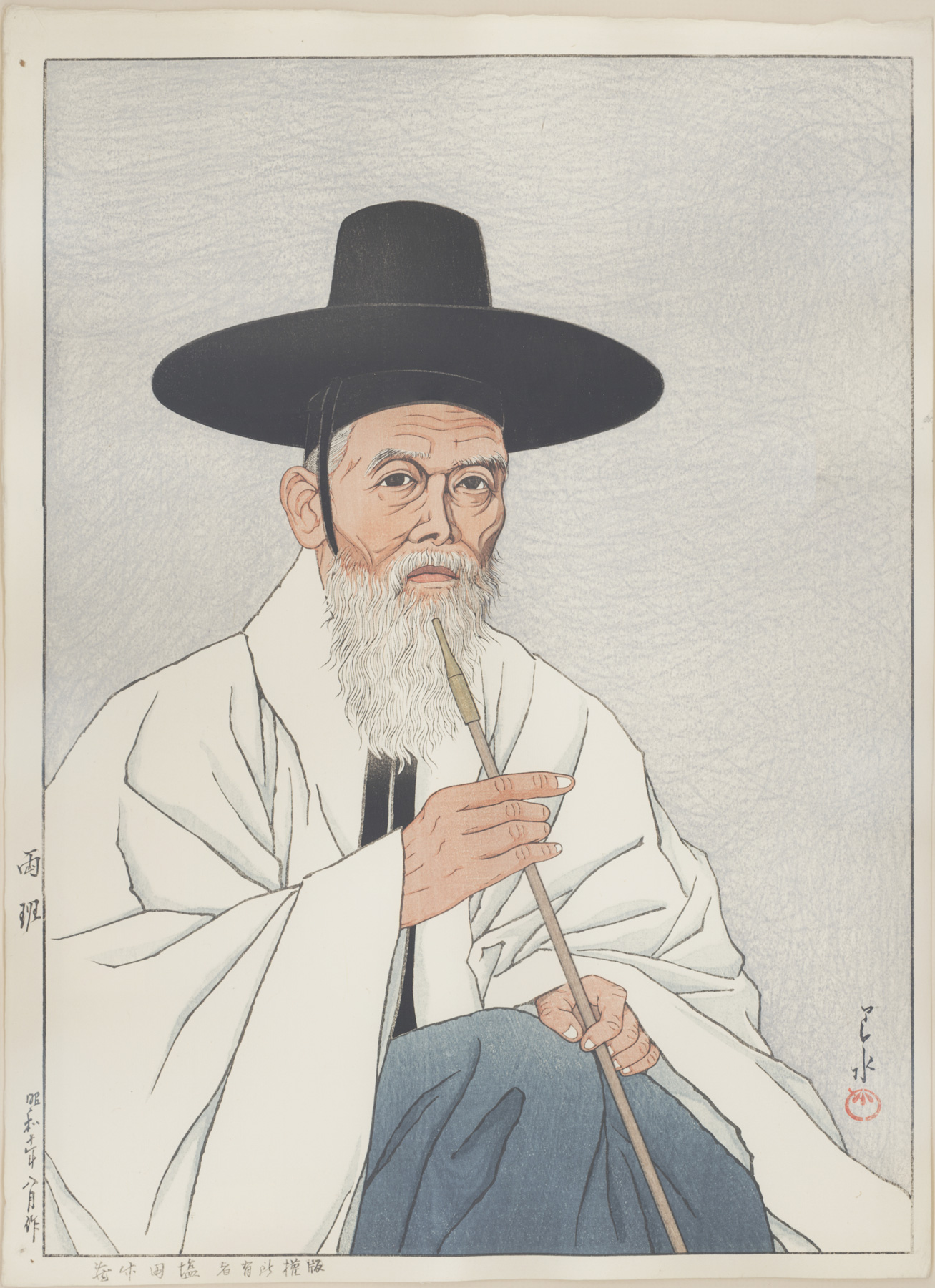

According to Paul Shiota, owner of T.Z.Shiota Gallery in San Francisco, Kawase Hasui (1883-1957) and the publisher Watanabe Shōzaburō (1885-1962) werecommissioned by his grandfather, T.Z. Shiota (Takezō Shiota) of San Francisco, to produce a limited edition of 300 prints of this image. Approximately 200 of theseprints are in circulation with the remainder being held by the Shiotafamily as of the year 2000. The print is an idealized portrait of a Korean gentleman-scholar created from a photograph. Paul did not know why his grandfather desired this image. Hisgrandfather also commissioned a print from Hasui and Watanabe of the Washington Monument(artist's catalog raisonné reference 358.)A Bit About T. Z. (Takezō) Shiota

Source: Blog of Darrel Karl: http://easternimp.blogspot.com/2017/06/ and http://bbs.fengniao.com/forum/2417646.html

Time has come for us to say, "Au Revoir" after faithfully created [sic] the world renown Chinatown by serving quality merchandise for 43 years.

To you, San Franciscans and friend customers, the members of the firm of T. Z. SHIOTA, wish to acknowledge each and every one of you for your past patronage and cooperation.

At this hour of evacuation when the innocents suffer with the bad, we bid you, dear friends of ours, with the words of beloved Shakespeare, "PARTING IS SUCH SWEET SORROW".

Till We Meet Again,

T. Z. Shiota

Catalog Raisonné Entry

Source: Kawase Hasui; TheComplete Woodblock Prints, Kendall Brown, Amy Reigle Newland, Amsterdam, Hotei Publishing, KITPublishers, 2003, P. 104.Yangban (literally, “two order”) were an elite class of civil andmilitary government officials in Korea, principally during the Chosonperiod (1392-1910). Yangban were exempt from obligatory labor ormilitary duty, and were meant to devote themselves to an education inthe Confucian classics and to advance according to the strictlyorganized examination system. The yangban class was endogamic, whichmeant they were prohibited from marrying and living together withnon-yangban.

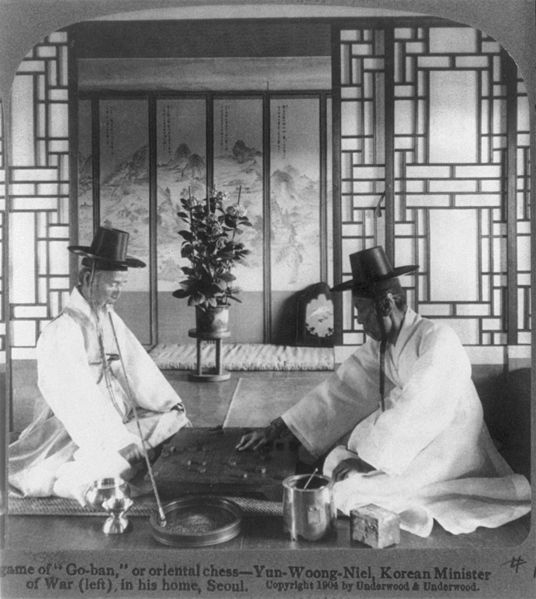

Yun-Woong-Niel, Korean Minister of War (left) in his home, Seoul. c. 1904 | Catalogue Raisonné image and entry 357 A yangban Work of August 1935 Hasui signature with Kawase Seal Publisher: Watanabe Shozaburo (unsealed) Commissioned by Shiota Tezeko |

Yangban in Korea

Source: North Korea: A Country Study. Andrea Matles Savada, ed., Washington: GPO for the Library of Congress, 1993. http://countrystudies.us/north-korea/26.htmInthe Chosn Dynasty, four distinct social strata developed: thescholar-officials (or nobility), collectively referred to as theyangban; the chungin (literally, "middle people"), technicians andadministrators subordinate to the yangban; the commoners or sangmin, alarge group composed of farmers, craftsmen, and merchants; and thech'mmin (despised, or base people, often slaves) at the bottom ofsociety. To arrest social mobility and ensure stability, the governmentdevised a system of personal tallies in order to identify peopleaccording to their status, and elites kept detailed genealogies, orchokpo.

In the strictest sense of the term, yangban referredto government officials or officeholders who had passed the civilservice examinations, which tested knowledge of the Confucian classicsand their neo-Confucian interpretations. They were the Koreancounterparts of the scholar-officials, or mandarins, of imperial China.The term yangban, first used during the Kory Dynasty (918-1392),literally means two groups, that is, civil and military officials. Overthe centuries, however, its usage became rather vague, so the term canbe said to have several overlapping meanings. A broader use of the termincluded within the yangban two other groups that could be consideredassociated with, but outside, the ruling elite. The first includedthose scholars who had passed the preliminary civil service examinationand sometimes the higher examinations but failed to secure governmentappointment. In the late Chosn Dynasty, there were many more successfulexamination candidates than there were positions. The second includedthe relatives and descendants of government officials because formalyangban rank was hereditary. Even if these people were poor and did notthemselves serve in the government, they were considered members of a"yangban family" and thus shared the aura of the elite so long as theyretained Confucian culture and rituals.

In principle, however,the yangban were a meritocratic elite. They gained their positionsthrough educational achievement. Although certain groups of persons(including artisans, merchants, shamans [mudang], slaves, and Buddhistmonks) were prohibited from taking the higher civil serviceexaminations, they formed only a small portion of the population. Intheory, the examinations were open to the majority of people, who werefarmers. In the early years of the Chosn Dynasty, some commoners mayhave been able to attain high positions by passing the examinations andadvancing on sheer talent. Later, talent was a necessary but not asufficient prerequisite for getting into the core elite because of thesurplus of successful examinees. Influential family connections werevirtually indispensable for obtaining high official positions.Moreover, special posts called "protection appointments" were inheritedby descendants of the Chosn royal family and certain high officials.Despite the emphasis on educational merit, the yangban became in a veryreal sense a hereditary elite. Thus, when progressive officials enactedthe 1984 Kabo Reforms, a program of social reforms, they found itnecessary to abolish the social distinctions between yangban andcommoners.

Below the yangban, yet superior to the commoners,were the chungin, a small group of technical and administrativeofficials. This group included astronomers, physicians, interpreters,and career military officers. Local functionaries, who were members ofan inferior hereditary class, were an important and frequentlyoppressive link between the yangban and the common people, and wereoften the de facto rulers of a local region.

Print Details

| IHL Catalog | #31 |

| Title | A Yangban 両班 |

| Series | |

| Artist | Kawase Hasui (1883-1957) |

| Signature |  |

| Seal | Kawase seal (see above) |

| Publication Date |  昭和十年八月作 a work of Shōwa 10th year, 8th month |

| Edition | First (and only) edition with no Watanabe publisher seal (as issued.) Edition size: 300 |

| Publisher | Watanabe Shōzaburō - commissioned by Shiota Takezō (T. Z. Shiota of San Francisco) |

| Impression | excellent |

| Colors | excellent |

| Condition | excellent |

| Miscellaneous |  版権所有者 塩田竹蔵 Hanken shoyūsha Shiota Takezō (Copyright holder, Shiota Takezō) |

| Genre | shin hanga (new prints) |

| Format | ōban tate-e |

| H x W Paper | 16 3/4 x 11 7/8 in. (42.5 x 30.2 cm) |

| H x W Image | 16 x 11 1/8 in. (40.6 x 28.3 cm) |

| Collections This Print | Los Angeles County Museum of Art M.73.37.173 (no seal, as issued); Carnegie Museum of Art 89.28.172 (no seal, as issued); Honolulu Academy of Arts 26246 (no seal, as issued) |

| Reference Literature | CatalogueRaisonné: Kawase Hasui; TheComplete Woodblock Prints, Kendall Brown, Amy Reigle Newland, Hotei Publishing, KITPublishers, 2003, p. 104, pl. 357; Modern Japanese Prints: The Twentieth Century, Amanda T. Zehnder, Carnegie Museum of Art, 2009, p.78; Japanese Woodblock Prints: The Reciprocal Influence between East and West, Lucille R. Webber, Brigham Young University Press, 1980, p. 90, fig. 73. |

8/20/2021