About This Print

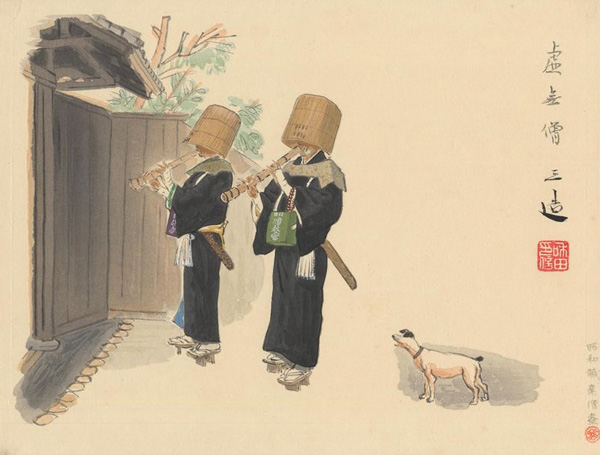

A later (post-War) re-issue by Kyoto Hangain of the pre-WWII design of two itinerant priests originally released by Nishinomiya Shoin between 1939 and 1941, as the twentieth print in the series Occupations of Shōwa Japan in Pictures.

As described in Memories of Shōwa: Impressions of Working Life by Wada Sanzō, each print was originally released with an explanatory sheet by Wada in Japanese "containing detailed information and personal insights."1 Some of the accompanying commentaries were also translated into English by "Glenn W. Shaw (1881-1961), a writer and teacher who moved to Japan in 1913."2 Below are Wada's comments from both the first edition published by Nishinomiya Shoin in 1939-1941 and the post-war second edition published by Kyoto Hangain, the successor to Nishinomiya Shoin.

[First edition, 1939-1941 by Nishinomiya Shoin] As monks from the Fuke sect (Zen Buddhism) or as an incidental job of samurai this profession enjoyed a distinct character and dignity. However, at some point it became a masked profession.However, while in terms of dress it has become more convenient than in the past, and they can now quickly see the state of their purse by peering from within their reed hood, they replace reciting the Heart Sutra with laying original songs on their shakuhachi (bamboo flute), such as Oiwake (Forked Road), Harusame (Gentle spring rain) and Tocchiriton.Among them are also those that left their rentalhouses in the suburbs and, carrying a reed hood and shakuhachi, hastily resolved to become a komusō.It is said that this will make a resonable living.This kind of vocational mask is not limited only to the komusō profession.3

1 Memories of Shōwa: Impressions of Working Life by Wada Sanzō, Maureen de Vries and Daphne van der Molen, Nihon no hanga, 2021, p. 14.

2 ibid.

3 ibid. p. 35

More Detail on the Komusō and the Shakuhachi

Source: http://panathinaeos.wordpress.com/2012/03/25/kaoru-kakizakai-a-modern-komuso-zen-priests-of-nothingness/ and Wikipedia http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Komus%C5%8D

Komusō 虚無僧 means “priest of nothingness” or “monk of emptiness".

The komusō monk of the Fuke school of Zen Buddhism flourished during the Edo era (1600-1868.) These mendicant monks wore straw baskets, tengai 天蓋, on their heads, denoting the absence of specific ego. The tengai was also used as a disguise by those trying to hide their identities.

Fuke started as early as 1254 by the priest Kakushin, who visited China and learnt there not only theology but music. Upon his return he wandered about Japan preaching and playing the flute.

Komusō practiced Suizen, which is meditation through the blowing of a shakuhachi 尺八, as opposed to Zazen, which is meditation through sitting as practiced by most Zen followers. Their songs (called honkyoku 本曲) were paced according to the players’ breathing and were considered meditation (suizen 吹禪) as much as music.

With the Meiji Restoration, beginning in 1868, the Fuke sect came under close scrutiny and was abolished 1871 due to the concerns that the many samurai and ronin opposed to the Restoration were disguising themselves as komusō.*

The very playing of the shakuhachi was officially forbidden for a few years. Non-Fuke folk traditions did not suffer greatly from this, since the tunes could be played just as easily on another pentatonic instrument. However, the honkyoku repertoire was known exclusively to the Fuke sect and transmitted by repetition and practice, and much of it was lost, along with many important documents.

When the Meiji government did permit the playing of shakuhachi again, it was only as an accompanying instrument to the koto, shamisen, etc. It was not until later that honkyoku were allowed to be played publicly again as solo pieces. “Shaku-hachi” means “one shaku eight sun” (almost 55 centimeters), the standard length of a shakuhachi.

The bamboo flute first came to Japan from China during the 6th century. The shakuhachi proper, however, is quite distinct from its Chinese counterpart– the result of centuries of isolated evolution in Japan.

When the Meiji government did permit the playing of shakuhachi again, it was only as an accompanying instrument to the koto, shamisen, etc. It was not until later that honkyoku were allowed to be played publicly again as solo pieces. “Shaku-hachi” means “one shaku eight sun” (almost 55 centimeters), the standard length of a shakuhachi.

The bamboo flute first came to Japan from China during the 6th century. The shakuhachi proper, however, is quite distinct from its Chinese counterpart– the result of centuries of isolated evolution in Japan.

*the early Meiji era was a time when the slogan "throw away the Buddha, abolish the monks" haibutsu-kishaku 廃佛棄釋 was heard as a response to the official policy of separation of Shinto and Buddhism.

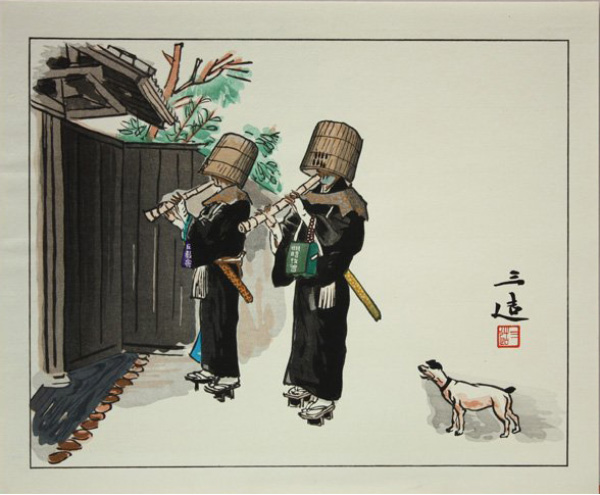

Below left is the first edition of this print as issued by Nishinomiya Shoin between 1939 and 1941. Kyoto Hangain reissued six prints form this series, including this print, in a smaller, chuban size (approx. 8 3/4 x 10 3/4 in.), edition as shown on the right sometime in the 1950s.

last revision:

First edition print as originally issued in 1939-1941 by Nishinomiya Shoin

A post WWII re-issue in a smaller (chuban) format by

the publisher Kyoto Hangain. One of six chuban size prints

in the series Japanese Life and Custom.

See IHL Cat. #1129

About the Series "Occupations of Shōwa Japan in Pictures"

Sources: website of Ross Walker Ohmi Gallery http://www.ohmigallery.com/DB/Artists/Sales/Wada_Sanzo.asp and website of USC Pacific Asian Museum "Exhibition - The Occupations of Shōwa Japan in Pictures: The Woodblock Prints of Wada Sanzō"

Note:

My special thanks to Shinagawa Daiwa, the current owner of Kyoto Hangain, for providing the below information (in a series of emails in July 2014) about Nishinomiya Shoin and Kyoto Hangain, both businesses started by his father Shinagawa Kyoomi. Shinagawa's current website can be accessed at http://www.amy.hi-ho.ne.jp/kyotohangain/

Wada’s major contribution as a woodblock print artist came through his 72 print 3-part series Occupations of Shōwa Japan in Pictures (Shōwa shokugyō e-zukishi), also translated as Occupations of the Shōwa Era in Pictures and Japanese Vocations in Pictures. The three part series was started during the Pacific War (1937-1945) in September 1938, was then interrupted by war shortages in 1943, and was restarted again after the war in January 1954. This series was a labor of love for Wada and he brought together woodblock print printers and carvers in Nishimomiya near Kobe to work on this project.

The war era prints were published by Wada through an old books store, Nishinomiya shoin 西宮書院 run by Shinagawa Kyoomi

品川清臣. Wada

planned a total of 100 designs, with two prints being issued each month. Wada's designs for the prints were rendered in watercolor and the finished prints beautifully captured the look-and-feel of those original watercolors. The series was an immediate hit, but was suspended after 48 prints (issued in two series) in 1943 due to war shortages.

After the war, the series was continued by the same publisher, Shinagawa Kyoomi, who had opened a new business in Kyoto, which he named Kyoto Hangain 京都版画院. (Shingawa's business in Nishinomiya had burned down during WWII.) At first Kyoto Hangain published re-prints of the earlier prints, but they went on to publish a third series of 24 prints, working closely with Wada, titled Continuing Occupations of Shōwa Japan in Pictures between November 1954 and September 1956.1 The post-war prints were popular with the Occupation's "deep-pocketed" military and civilian personnel and the series was "featured in an article of the Tokyo edition of the United States military newspaper Stars and Stripes."2 Shinagawa also published a six print portfolio in the 1950s titled Japanese Life and Customs, consisting of six of the prints from the earlier two series in a reduced chuban size, which is also part of this collection.

Occupations of Shōwa Japan in Pictures has been praised for showing “the complexity of Shōwa society…. capture[ing] the pulse of Japanese life during the tumultuous decades of the 1930s, 1940s and 1950s”3 and condemned as providing a “visual message of subtle or blatant propaganda in support of government-sponsored ideas.”4

It is interesting to see how the commentary, written by the artist, that accompanied each print in the pre-war releases was softened for the post-war re-issues by Kyoto Hangain. All references to soldiers being away from home (as Japanese armies were marching through Asia when the series was originally released) or references to Imperial Japan have been stripped away and the commentary becomes innocent, folk-like and appealing to the post-war occupying forces. (For example, see the prints Women Weavers and Picture Card Show which provide the artist's original commentary and a full transcript of the English text attached to the folders of the post-war re-issued prints.)

1 Keizaburo Yamaguchi gives the publication dates of the post-War series as January 1954 through autumn 1958. (Ukiyo-e Art 16, 1967): 39-42.

2 "Out of the Dark Valley: Japanese Woodblock Prints and War, 1937-1945," Kendall H. Brown,p. 82 appearing in Impressions, The Journal of the Ukiyo-e Society of America, Inc., Number 23, 2001.

3 Pacific Asia Museum website http://www.pacificasiamuseum.org/_on_view/exhibitions/2004/occshowa.aspx

4 Light in Darkness: Women in Japanese Prints of Early Shōwa (1926-1945), Kendall H. Brown, et. al., Fisher Gallery, University of Southern California, 1996, p. 18.

2 "Out of the Dark Valley: Japanese Woodblock Prints and War, 1937-1945," Kendall H. Brown,p. 82 appearing in Impressions, The Journal of the Ukiyo-e Society of America, Inc., Number 23, 2001.

3 Pacific Asia Museum website http://www.pacificasiamuseum.org/_on_view/exhibitions/2004/occshowa.aspx

4 Light in Darkness: Women in Japanese Prints of Early Shōwa (1926-1945), Kendall H. Brown, et. al., Fisher Gallery, University of Southern California, 1996, p. 18.

Print Details

| IHL Catalog | #1039 |

| Title/Description | 虚無僧 - Komusō [number 20] |

| Series | Occupations of Shōwa Japan in Pictures, Series 1 (also seen translated as "Compendium of Occupations in the Shōwa Era" and "Japanese Vocations in Pictures") Shōwa shokugyō e-zukushi 昭和職業繪盡 (also seen written as 昭和職業絵尽し and 昭和職業繪盡し), daiishū (第一輯) |

| Artist | Wada Sanzō (1883-1967) |

| Signature | 三造 Sanzō |

| Seal |  |

| Publication Date | c. 1950 (originally 1939-1941) |

| Publisher | Kyoto Hangain 京都版画院  hanmoto Kyoto hangain suru Ōno 版元 京都版画院 摺大野 |

| Edition | A second edition of the print first published by Nishinomiya shoin between 1939 and 1941. As originally issued by Nishonimiya shoin this print was the 20th in series 1. It is believed that all the pre-WWII woodblocks for this series were destroyed in Allied air raids in 1945 and that all post-WWII impressions by Kyoto Hangain, the business started by Daiwa Shinagawa the owner of Nishomiya shoin after WWII, were made from re-cut blocks. |

| Carver | |

| Printer | Ōno 大野 (see publisher's seal above) |

| Impression | excellent |

| Colors | excellent |

| Condition | fair - toning; borders unevenly trimmed; minor tears |

| Genre | shin ukiyo-e |

| Miscellaneous | originally released by Nishinomiya Shoin as print number 20 in series 1 |

| Format | dai-oban |

| H x W Paper | 11 7/8 x 16 1/2 in. (30.2 x 41.9 cm) |

| Collections This Print | Himeji City Museum of Art Ⅲ-183-20 (dated "1939~1940年"); Art Gallery of Greater Victoria 1997.020.010 (edition unknown); San Diego Museum of Art 1965.77.s |

| Reference Literature | Memories of Shōwa: Impressions of Working Life by Wada Sanzō, Maureen de Vries and Daphne van der Molen, Nihon no hanga, 2021 |

8/9/2021

6/22/2021

6/7/2021

12/5/2018

, monks --7eb027ed4dec120.jpg)