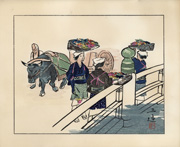

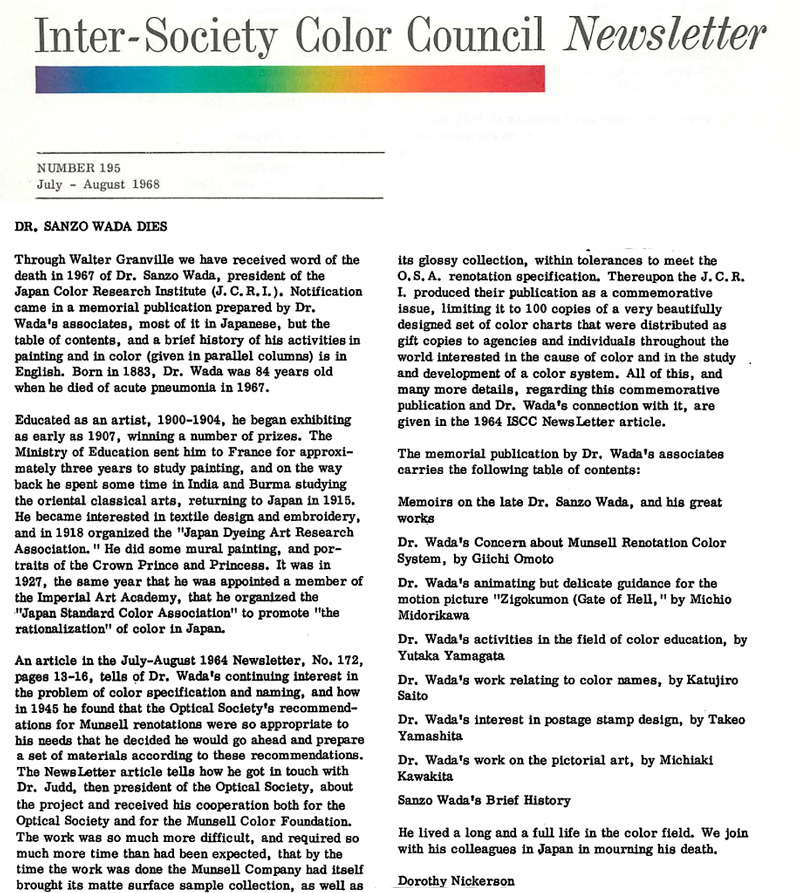

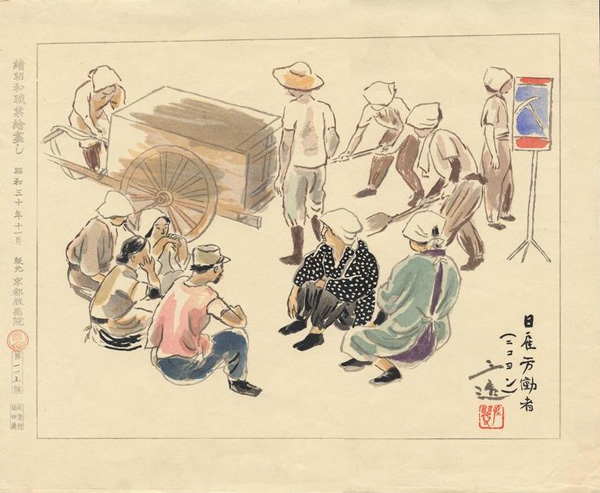

Pilgrims, print number 2,

from the series

Occupations of Shōwa Japan in Pictures, Series 1, 1939

IHL Cat. #1306

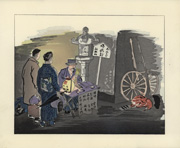

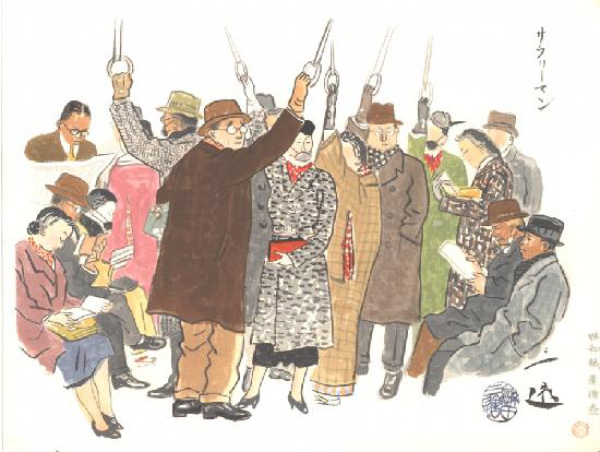

from the series

Occupations of Shōwa Japan in Pictures, Series 1, 1939

IHL Cat. #1474

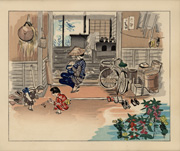

Flower Vendors, print number 21,

from the series

Occupations of Shōwa Japan in Pictures, Series 1, 1950

(originally 1941)

IHL Cat. #1003

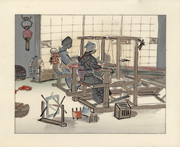

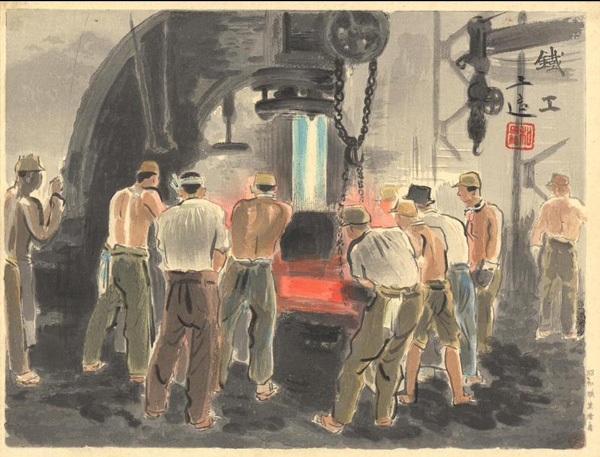

from the series

Occupations of Shōwa Japan in Pictures, Series 1, 1940-1941

IHL Cat. #1653

-intentionally left blank-

IHL Cat. #1010

Oharame's House, 1954

IHL Cat. #1076

Girls Playing Otedama, c. 1950s

IHL Cat. #2071

Dollmakers, print number 7,

from the series

Occupations of Shōwa Japan in Pictures, Continuing, Series 3, March 1955

IHL Cat. #2264

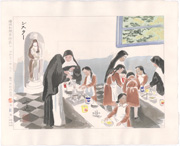

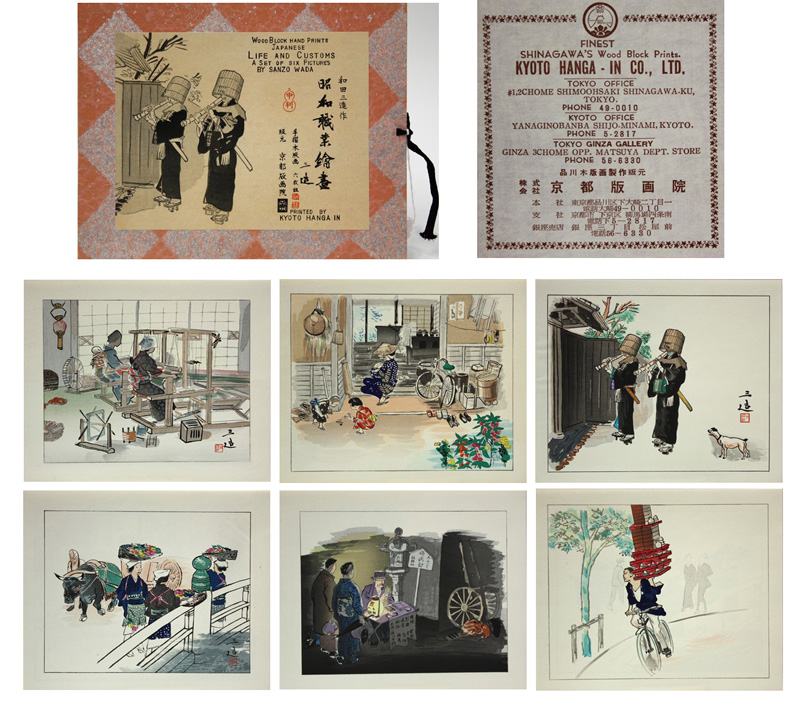

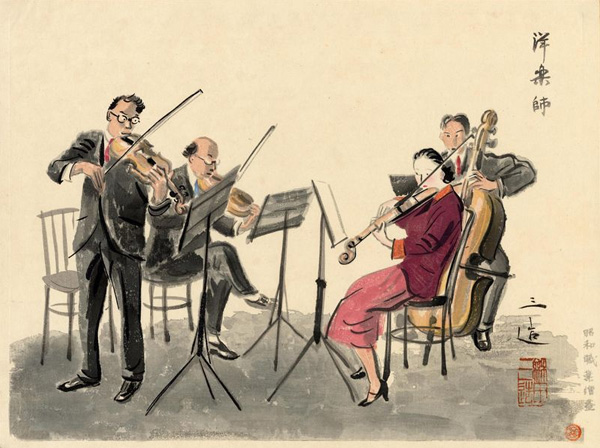

Profile 略歴 | Wada Sanzō 和田三造 (March 3, 1883–August 22, 1967) A multi-talented artist who gained early fame as a Western-style oil painter, his career spanned the late Meiji-era through the mid-twentieth century. He may be best known in the West for his 1955 Academy Award for costume design for the movie Gates of Hell and for his pioneering work on color theory, begun in the 1920s and still employed today. His three-part woodblock print series Occupations of Shōwa Japan in Pictures, issued before (series 1 and 2) and then after WW-II (series 3) is his most well-known print work. |

Biography

Born on March 3, 1883 in Hyōgo prefecture in the western Kansai region of Honshu, the main Japanese island, Sanzō was the fourth son of Wada Bunken? (和田文硯), an official physician in the Kutsuki domain (current day Fukuchiyama City in Kyoto prefecture) who worked as a doctor at the Ikuno Mine and at an elementary school. One of Sanzō's elder brothers Shōzō studied Western painting at the Tokyo Bijutsu Gakkō (Tokyo School of Fine Arts), becoming friends with the painter Shirataki Ikunosuke (1873-1960), died prematurely at the age of 20.

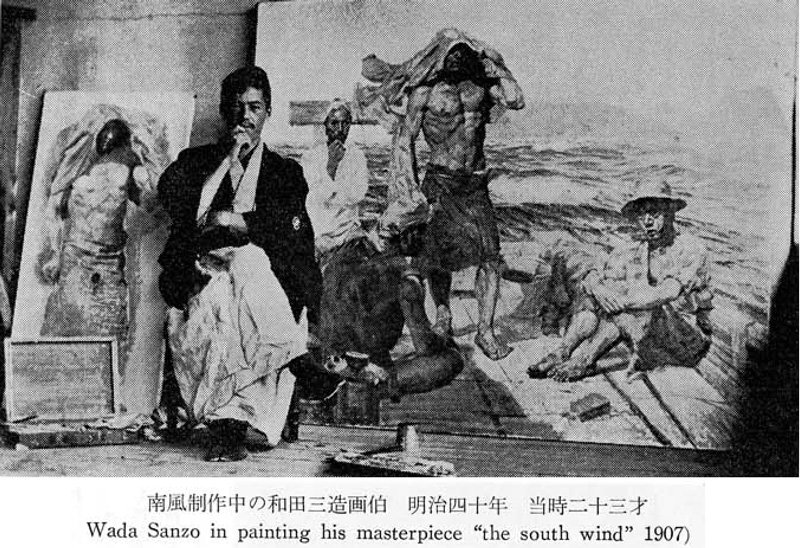

In 1899, at the age of sixteen, and over the objection of his father, he dropped out of the Fukuoka Prefectural Shuyukan Middle School to study painting in Tokyo. Nagao Kenichi 長尾建吉 (1860-1938), a lacquer craftsman and a creator of custom picture frames for painters (and possibly, also, Shirataki Ikunosuke) convinced the famous Western-style (yōga) oil painter Kuroda Seiki (1866-1924) to take on Sanzō as a houseboy and Wada was to study at Kuroda’s Hakubakai (White Horse Society), going on to attend the Tokyo School of Fine Arts in 1901, where he studied Western-style painting, graduating in 1904. In 1905 he exhibited and won an award at the 10th Hakubakai exhibition for his painting Bokujō no banki (Evening return at the pasture) and in 1907 he exhibited his painting Nampū (South Wind) winning the Second Prize (the highest award) at the first Ministry of Education art exhibition, Bunten. South Wind garnered him early acclaim from critics and the public and was so well regarded that he was allowed to exhibit at future exhibitions without the usually required prior approval.

South Wind, 1907

oil on canvas, 151.5×182.4 cm

O00021

The National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo

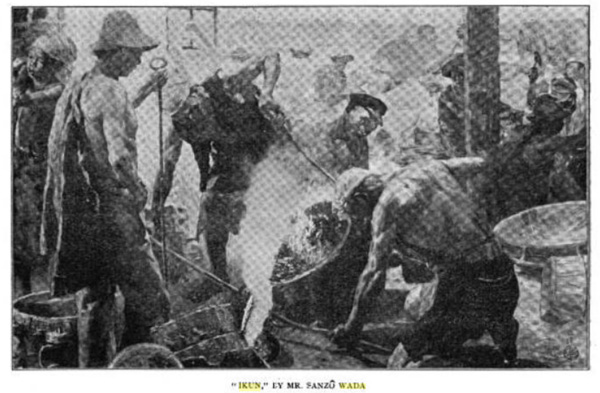

Following another Second Prize at the Bunten in 1908 for his painting Ikun (Glowing/Red Smoke or Mighty Smoke), see picture and caption below, the Ministry of Education sent him to Europe in 1909 to study painting, craft and film, a tribute to Sanzō’s multiple creative talents. While in France, he became friendly with the artist Yamamoto Kanae (1882-1946), who is credited with creating the first Sōsaku Hanga (Creative Print.) He remained in Europe seven years, until 1914, and returned home the following year via India, Burma and Java studying textiles and the art of those areas. He would return to India in 1916 to further study Indian art.

It is at once intimate and monumental; the viewer is on a small fishing boat, a trade with strong cultural resonance in Japan and one that lacks any of the trappings of Western-style modernity. However, the central figure stands tall, dominating the scene with a muscular torso and solid legs and arms, feet planted firmly and confidently on the deck, and his gaze set towards the horizon. The style of his figure clearly uses Western classical art as a model (the nose in particular seems for more Roman or Greek than Japanese), but the scene is so intimately Japanese that the image was embraced by the government and hung for many years in government buildings in Tokyo.1

It can be said that Wada was the epitome of an establishment artist, painting for the Imperial family, government and military. In 1917, at the age of 34, he was named a juror for the government’s Bunten exhibitions and was to remain a juror through its successor organization, Teiten. In 1927 he was appointed Member of the Imperial Art Academy (Teikoku Bijutsu-in) and in the same year started teaching at the prestigious Tokyo School of Fine Arts, where he taught until 1944.3

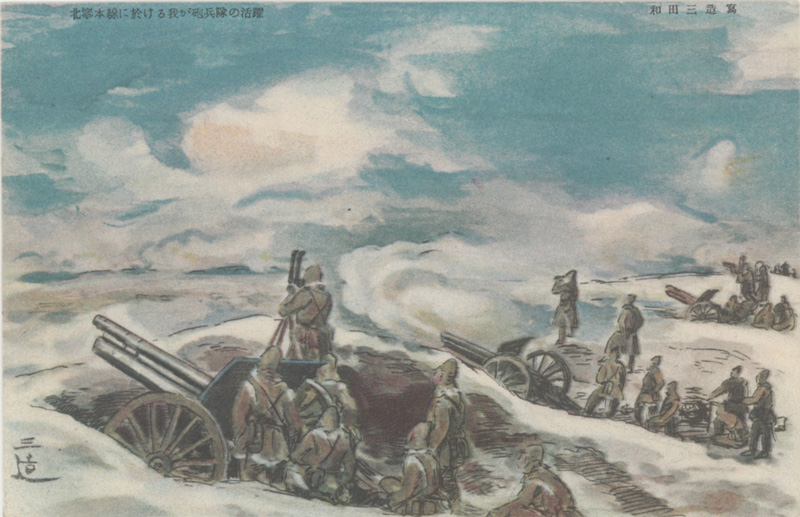

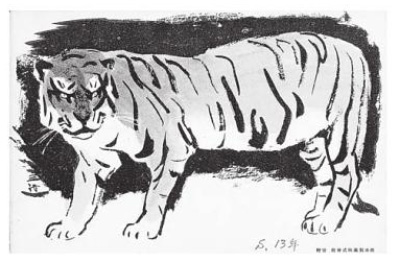

The dauntless tiger crosses one thousand leagues, fearful of nothing. It is said that he topples all enemies. Thanks to our incomparably brave troops, ferocious like the tiger, an eternal peace is being established in Asia. We wish military success and long life to those troops who are being deployed this spring.” - as captioned6 | Success of Our Artillery at the Main Line of Beining Railway, 1932 満州 北寧本線に於ける砲兵隊活躍 和田三造 |

In his later years he pursued both oil and nihonga (Japanese ink) painting, was active in crafts, designed tapestry theater curtains, and in 1958 he was chosen a Person of Cultural Merit by the Japanese government.

He died of pneumonia on August 22, 1967.

His work in color, textiles and film lead him into costume design and in 1955 he won an American Motion Picture Academy Award for color costume design for the film Gates of Hell, on which he also served as the director’s color consultant.8

This book is a collection of 348 color combinations originated by Sanzo Wada (1883-1967) who, in that time of increasingly avant-garde and diversified use of color, was quick to focus on the importance of color and laid the foundation for contemporary color research. Sanzo Wada was active as an artist, art school instructor, costume designer for the movies and the theater, and kimono and fashion designer who employed his extensive and versatile talents to do innovative work that centered primarily on visual perception and form. - As quoted on the Library World OPAC website.

Occupations of the Shōwa Era in Pictures has been praised for showing “the complexity of Shôwa society…. capture[ing] the pulse of Japanese life during the tumultuous decades of the 1930s, 1940s and 1950s”12 and condemned as providing “visual message of subtle or blatant propaganda in support of government-sponsored ideas.”13

Occupations of Shōwa - a few examples from each of the three series

To see the three series in their entirety please view the website of the Ohmi Gallery at

It is unclear whether Wada had created woodblock prints prior to this series, but he was certainly well-familiar with the genre through his early association with Kanae and his work with the yōga artist and printmaker Ishii Hakutei (1882-1958). At an unknown date after WWII (although one source supposes a date of c. 1930s) he authored the book The Steps in Wood block Printing: Maiko-san, published by Kyoto Hangain which includes sixteen woodblock prints taking the reader through the process of creating the print Maiko-san shown below. While most of his post-WWII prints were published by Kyoto Hangain, including two prints depicting the seven lucky gods, a print of the imperial palace, two portraits of dogs, and various prints depicting Kyoto-area life, he also created a series of prints titled Life of Kyoto, consisting of six prints, published by the little known publisher Miyawaki Bifu Ōgi.

Modern Japanese society and culture is often imagined in dramatic conflict between western-style modernity and enduring tradition. This tension emerged in the Meiji era (1868-1912) and continues today, but was most pronounced during the early Shôwa period (1926-1989). This was a time when the nation rejected European values as part of war ideology, then enthusiastically re-embraced western culture during the Allied Occupation of 1945-52.

The complexity of Shôwa society is glimpsed in two series of color woodblock prints designed by painter Wada Sanzô (1883-1967): The Occupations of Shôwa Japan in Pictures first published in a 48-print series between 1938 and 1941; and the 24-print Continued Occupations of Shôwa issued from 1954 to 1956. These images capture the pulse of Japanese life during the tumultuous decades of the 1930s, 1940s and 1950s. In the words of their publisher Shinagawa Kiyoomi, this is truly the “ukiyo-e of Shôwa.”

Wada was uniquely qualified to capture the contradictions of modern Japan. Trained in academic oil painting, Wada was an establishment artist, painting for the Imperial family, government and military, teaching at the prestigious Tokyo School of Fine Arts, and serving as co-president of the Artist’s Patriotic League from 1943-45. Wada also explored Asian artistic traditions, studying textiles in India and Kyoto, and ending his career by painting in the native nihonga style and designing tapestry theater curtains. Wada’s pioneering color research resulted in his winning an American Motion Picture Academy Award in 1955 for color costume design for the film Gates of Hell.

Wada was noted for his figure drawing and luminous color—qualities wonderfully displayed in his prints. Prints from his watercolor originals display the refined technique of Japanese woodblock printing. Wada’s prints also raise vital issues about the qualities of Japanese society and culture that allowed the nation to quickly adjust from anti-western militarism to pro-American reconstruction. Wada’s Occupations series suggest that a focus on everyday life — whether with new “western” trends, remnants of traditional culture or a synthesis of the two — provide a critical link between war-era nationalism and the commodification of traditional Japanese life basic to post-war “Americanization.”

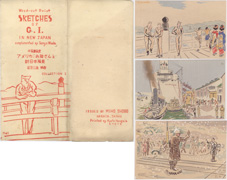

USC Pacific Asia Museum presentation is the first time the two Occupation series will be shown in their entirety. Exhibited alongside some of the images are the brief essays that Wada wrote for them. In addition, the show will include some of Wada’s various post-war prints showing traditional customs of Kyoto, and his three-postcard series Sketches of G.I. in New Japan.

All of the prints, lent by a local collector, were originally assembled by Richard Miles, a long-time friend of USC Pacific Asia Museum. The exhibition is curated by Kendall H. Brown, specialist in modern Japanese prints and a professor of art history at California State University, Long Beach.

1 Spectacles of Authenticity: The Emergence of Transnational Entertainments in Japan and America, 1880-1905, Hsuan Tsen (A dissertation), August 2011, Stanford University.

2 International Futurism in Arts and Literature, Günter Berghaus, Walter de Gruyter, 2000. Series: European cultures, v. 13, p. 250.

3 I have seen two dates given for the start of his teaching, 1927 (Japan wikipedia) and 1932 (Merritt, Modern Japanese Woodblock Prints.)

4 Politics and Culture in Wartime Japan, Ben-Ami Shillony, Clarendon, 1981, p. 119; Light in Darkness: Women in Japanese Prints of Early Shōwa (1926-1945), Kendall H. Brown et. al., Fisher Gallery, University of Southern California, 1996 p. 18-19.

5 "As in the realm of politics, the patriotic mood generated by an all-out war, on top of the repressive measures of the government, created a remarkable consensus in the fields of thought, literature, and the arts. In a country like Japan, where the group values of loyalty and harmony were still considered very important, there was less need of coercion in order to line up the intellectuals, the writers, and the artists behind the nation in arms than there was in other countries." - Politics and Culture in Wartime Japan, Ben-Ami Shillony, Clarendon Press, 1991, p. 119-120.

6 Nature of the Beasts: Empire and Exhibition at the Tokyo Imperial Zoo, Ian Jared Miller, University of California Press, 2013, p. 103-104.

7 Books on Colour Since 1500: A History and Bibliography of Colour Literature, ed. Roy Osborne, University

Publishers, 2013, p. 133.

8 Japan Digest, Volume 7, 1955, p. 30.

9 Hanshan Tang Books, London List 165 www.hanshan.com/pdf/l65.pdf

10 Keizaburo Yamaguchi gives the publication dates of the post-War series as January 1954 through autumn 1958. (Ukiyo-e Art 16, 1967): 39-42.

11 "Out of the Dark Valley: Japanese Woodblock Prints and War, 1937-1945," Kendall H. Brown,p. 82 appearing in Impressions, The Journal of the Ukiyo-e Society of America, Inc., Number 23, 2001.

12 Pacific Asia Museum website http://www.pacificasiamuseum.org/_on_view/exhibitions/2004/occshowa.aspx

13 op. cit., Light in Darkness, p. 18.