About This Print

[First Edition, 1939-1941, published by Nishinomiya Shoin]

Picture Card Show

At the street corner the young children are waiting for the picture show storyteller, who performs spoken theater.

When the scene does not change, the children get bored so it is a good technique to offer them sweets while chattering away.

It is only natural that the authorities have recently continued to focus on good guidance for this profession as it should be a part of a system that can be used to foster ideas through a voice on the street.

[alternate translation of above paragraph: It is indeed natural that the authorities have recently been making efforts to lead in the right direction this business [the picture card show] that may well be employed as a valuable organ to … develop their [children’s] thought.]

The curiosity of candy and dialogue and the accompanying monetary compensation is an interesting business relationship.

When he finds a good place for his business on the street,he stops and makes ready the pictures illustrating his stories in the [sic]case on his bicycle. The he calls out“Come and look! A grand picture show you’ve never seen!” striking the woodenclappers to attract attention.

Soon a crowd of children gather from all directions. The story-teller is very skilful [sic] intelling the story, immitating [sic] the voices of the various people in thestory.

After the story is over, he sells candies. A pictorial story-teller is a Pide-piper[sic] of Hamelin in Japan, and the children are like the rats running after thepiper.

- Depicted by Sanzo Wada. Printed by KYOTO-HANGA-IN

During Japan’s Fifteen Year War (1931-1945), kamishibai (紙芝居) plays were one of the most widely distributed and frequently accessed media used to transmit propaganda messages about the “sacred war” (聖戦) to audiences in Japan (naichi) and the colonies (gaichi). Originally a street performance art for children that celebrated the earthy and lurid, kamishibai was repurposed by government agencies to address adults as well, and to convey to all its audiences important messages—through illustrations and script—encouraging them to support the war effort. This presentation will analyze the way the concepts of sacred and profane were deployed in the service of political persuasion.

A Critical View

Source: Light in Darkness: Women in Japanese Prints of Early Shōwa (1926-1945), Kendall H. Brown, et. al., Fisher Gallery, University of Southern California, 1996, p. 12.

In the introduction to the catalog of the exhibition Light in Darkness: Women in Japanese Prints of Early Shōwa (1926-1945), Dr. Kendall H. Brown comments on Wada's series and specifically this print as follows:

The best examples of these two characteristics [portraying women's jobs in an idealized and romanticized manner] are found in Wada Sanzo’s Occupations of Showa Japan in Pictures, a set of at least forty-eight prints published originally between 1939 and 1942. The majority of these wartime prints show male occupations but give little sense of Japan’s military involvements or even Japan’s status as a highly industrialized country. (These characteristics may account for the popularity of the series when reissued after the war.) Only a few prints show military men, and, not surprisingly, they display soldiers in non-military activities such as relaxing in their bunks or studying. However, the underlying political function of the series is made explicit in Picture Card Show. Here a soldier uses a painting, or perhaps a print, to lecture a group of neighborhood children who watch with dutiful attention. In a commentary issued with the print [as originally issued prior to the War], Wada writes that “It is indeed natural that the authorities have recently been making efforts to lead in the right direction this business [the picture card show] that may well be employed as a valuable organ to…develop their [children’s] thought."

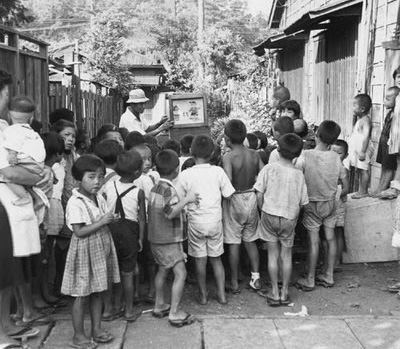

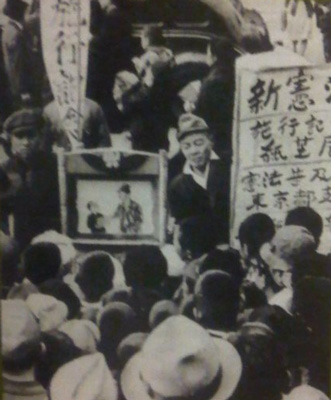

Picture story teller c. 1950s |  Picture teller announcing the post-War new constitution (新憲法) |

About the Series "Occupations of Shōwa Japan in Pictures"

Sources: website of Ross Walker Ohmi Gallery http://www.ohmigallery.com/DB/Artists/Sales/Wada_Sanzo.asp and website of USC Pacific Asian Museum "Exhibition - The Occupations of Shōwa Japan in Pictures: The Woodblock Prints of Wada Sanzō"

Note:

My special thanks to Shinagawa Daiwa, the current owner of Kyoto Hangain, for providing the below information (in a series of emails in July 2014) about Nishinomiya Shoin and Kyoto Hangain, both businesses started by his father Shinagawa Kyoomi. Shinagawa's current website can be accessed at http://www.amy.hi-ho.ne.jp/kyotohangain/

2 "Out of the Dark Valley: Japanese Woodblock Prints and War, 1937-1945," Kendall H. Brown,p. 82 appearing in Impressions, The Journal of the Ukiyo-e Society of America, Inc., Number 23, 2001.

3 Pacific Asia Museum website http://www.pacificasiamuseum.org/_on_view/exhibitions/2004/occshowa.aspx

4 Light in Darkness: Women in Japanese Prints of Early Shōwa (1926-1945), Kendall H. Brown, et. al., Fisher Gallery, University of Southern California, 1996, p. 18.

Print Details

| IHL Catalog | #1004, #983, #1542 | |||

| Title/Description | 紙芝居 [kamishibai] - Picture Card Show, [print number 11] | |||

| Series | Occupations of Shōwa Japan in Pictures, series 1 Shōwa shokugyō e-zukushi 昭和職業繪盡 (also seen written as 昭和職業絵尽し and 昭和職業繪盡し), daiishū (第一輯) | |||

| Artist | Wada Sanzō (1883-1967) | |||

| Signature | 三造 Sanzō | |||

| Seal |

| |||

| Publication Date | 1950-1951 (originally 1939-1941) | |||

| Publisher |

| |||

| Edition | second edition First published by Nishinomiya shoin in 1939-1941, this collection's three states of the second edition were published c. 1950 from re-cut blocks, as it is believed that all the pre-WWII woodblocks were destroyed in Allied air raids in 1945. It is believed that all post-WWII impressions by Kyoto Hangain were made from re-cut blocks. | |||

| Carver | ||||

| Printer | Ōno 大野 (see publisher's seal above) | |||

| Impression | IHL Cat. #1004 - excellent IHL Cat. #983 - excellent IHL Cat. #1542 -excellent | |||

| Colors | IHL Cat. #1004 - excellent IHL Cat. #983 - excellent IHL Cat. #1542 - excellent | |||

| Condition | IHL Cat. #1004: fair - multiple vertical folds, a few spots of dirt and foxing; mounting remnants top verso from removal from original folio IHL Cat. #983: good - stains in upper right of image; paper flaw to left of signature and bottom margin; mounting remnants from top verso from removal from original folio IHLCat.#1542: excellent - minor handling creases | |||

| Genre | shin hanga | |||

| Miscellaneous | ||||

| Format | dai-oban | |||

| H x W Paper | IHL Cat. #1004: 10 7/8 x 15 7/8 in. (27.6 x 40.3 cm) IHL Cat. #983: 11 1/4 x 15 1/2 in. (28.6 x 39.4 cm) IHL Cat. #1542: 11 5/8 x 16 1/8 in. (29.5 x 40.1 cm) | |||

| Collections This Print | Himeji City Museum of Art Ⅲ-183-11 (dated "1939~1940年") | |||

| Reference Literature | Light in Darkness: Women in Japanese Prints of Early Shōwa (1926-1945), Kendall H. Brown, et. al., Fisher Gallery, University of Southern California, 1996, p. 13, cat. 11; Memories of Shōwa: Impressions of Working Life by Wada Sanzō, Maureen de Vries and Daphne van der Molen, Nihon no hanga, 2021 |