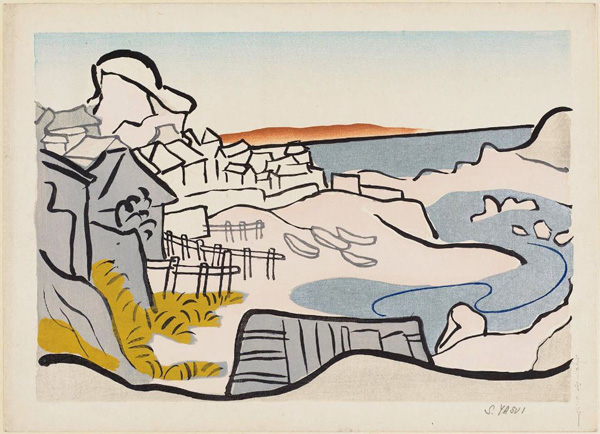

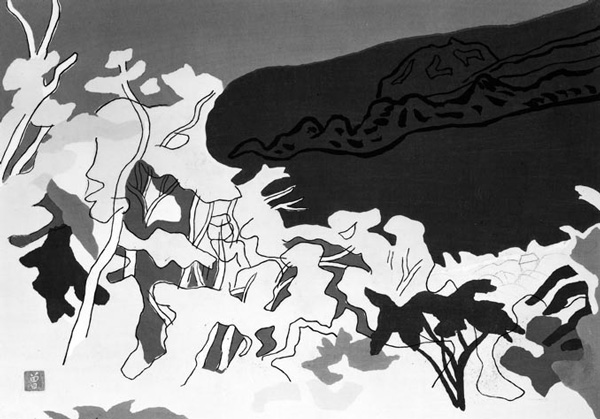

| Girl in New Year Clothes, 1933 IHL Cat. #905 | Autumn at Lake Towada, 1935 IHL Cat. #1111 | Oirasegawa, c. 1956 IHL Cat. #2011 |

Biography

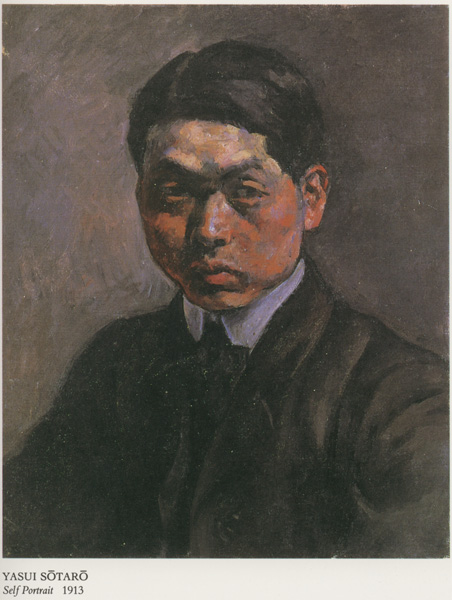

1933 photo 1933 photo | Yasui was born into a Kyoto merchant family that wholesaled cotton-goods. While his parents intended to have their son join the family business, sending him to Kyoto City Commercial School, Yasui’s desire to be an artist drove him to switch to Shōgo-in Institute of Western Art (Shōga-in Yōga Kenkyū-jo) at the age of 16, and later to the Kansai Academy of Art (Kansai Bijutsu-in), where he was taught by Asai Chū (1856-1907) and Kanokogi Takeshirō (1874-1941), leading Western-style artists of the time. In recalling Yasui’s time at the Kansai Academy of art fellow painter Ogawa Chikami recollects: “Yasui had the simplicity and sturdiness of the cotton goods his father sold, and his pictures were dark and tastefully severe…. Here was the tall Yasui, with his crew-cut hair, walking around shamelessly in the main streets of Kyoto in khaki work clothes splattered with paint – a sight that was indeed unusual in the Kyoto of those days.”1 In a period when Post-Impressionism was exerting the most influence on young Japanese artists studying in the Western-style, the dream of many of these artists was to study in Paris2 and in 1907, at the age of 19, following the death of his teacher Asai, Yasui traveled to France where he was to live for seven years, primarily in Paris. “During that period, he received a renewed grounding |

in painting through his art schoolstudies and absorbed even more from being exposed to the art of his time on itshome ground, in the museums and galleries of Paris. He was deeply impressed byPissarro, Renoir, and especially Cézanne.”3

Like many students of Asai Chū, Yasuiinitially studied with the historical painter Jean-Paul Laurens (1838 – 1921)at the Académie Julian, founded in 1868. In 1907, inspired by the posthumous Cézanne retrospective at the Salon d'Automne, he left the academy todevelop a more personal style and as he later wrote,“to see nature through the Master’s eyes.”4

While at the Académie, Yasui was considered aparticularly brilliant student and his sketches and paintings regularly tookprizes at their shows. As with otheryoung painters, Yasui took up pleine air painting while at the Académie and begantrips to the countryside to paint, eventually abandoning academic training inorder to develop a more individual style.

In 1914, at the outbreak of WWI, Yasui along with other,but not all, Japanese painters returned to Japan. Upon his return, he became active in the Nika-kai5 (formed in opposition to the official Bunten exhibition) and in the1915 Nika Exhibition his European work attracted enormous attention from bothartists and the general public, demonstrating “just how accomplished the newgeneration of Japanese painters could become when freed from the earlieracademic training still prevalent in Japanese teaching circles.”6

Following this initial success, while Yasuji continued toproduce work, he wrestled with trying to “accommodate what he had learned inFrance to his own temperament and to his new environment. The quality of light, he came to realize, wassufficiently different in Japan from the fabled luminosity of France that itwas necessary to create new techniques to render it. Further, some of the painting materialsavailable in Japan did not produce the same effects as those the painter hadused in France. In Yasui’s view, it wasnot until 1929 that he found himself again.”7

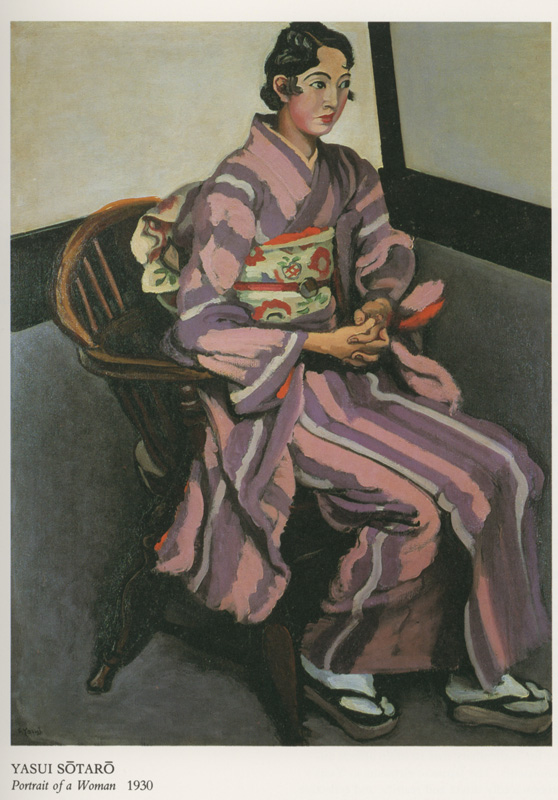

| For Yasui, finding himself involved his transition fromlandscape, still lifes, and genre painting to portraiture where his greatest talent lay. Beginning in 1929 with his showing of severalportraits of a young woman clad in kimono (see Portrait of a Woman, 1930 left), critics began speaking of a “Yasuistyle,” described as a style “in which clear lines and rich, mellow colors arecombined.”8 Histransition to portraiture was to secure Yasui an important position in the Tokyo artworld. The 1930s saw a maturing of Yasui’s style whichsynthesized the “Western-style naturalisticrepresentation that he had perfected in France, the influences of modernistart, especially Cézanne, and the heritage of East Asian art, particularly thetwo-dimensional treatment of space and arbitrary light source.”9 Through the 1930s and up until his death, Yasui “createdwork after work that his public felt represented a truly contemporary andauthentically Japanese vision. His colorwere dynamic, and his ability to portray psychological elements of his portraitsitters was highly developed. [H]isgrowing ability to simplify forms and take delight in flat and abstract shapesrepresented for many a resurgence of a truly Japanese quality in his art. Some critics traced these accomplishments, asthey did those of Umehara10, to their Kyoto background.”11 |

A 1934 photo of Yasui painting the portrait of Mr. Tamamushi Ichiroichi, principal of Daini Kotogakko, a high school under the prewar education system. On the occasion of his retirement, the school asked Yasui to paint a portrait. The full-length portrait produced then was submitted to the Nikaten and extolled as “the greatest portrait on record.” The finished painting Portrait of Mr. Tamamushi, 1934, in the collection of the Tōhoku University Archives, is shown on the right.

In 1935 he was made a member of the Imperial Art Academy,whereupon he left the Nika-kai. In 1936he was instrumental in the organization of the Issui-kai, an organization ofWestern-style artists whose purpose was “to honor pure and correct art,” andwho limited their membership to artists who created realist works.12

In 1944 he became a teacher at the Tokyo School of FineArts (Tokyo Bijutsu Gakkō) and a court artist (teishitsu gigei-in)13, but his artistic life proceeded unabated. In 1949, he became the first chairman of the Japan Artist's Association Nihon bijutsuka renmei 日本美術家連盟.14 He devoted himself to instructing youngartists until 1952, in which year, with his old friend Umehara Ryūzaburō,he received the Order of Cultural Merit.

His last years were spent at Yugawara in KanagawaPrefecture, where he pursued his spare style ofpainting. In 1955 at sixty-seven he diedof heart failure after contracting pneumonia. A collection of his writings, Gakano me (“An Artist’s Eye,” Zauhō Kankōkai, 1956) was publishedposthumously.

The Artist’s Woodblock Prints

Prints by Yasui are rare, but he saw prints as a useful step in oil painting, believing that the making of prints "is instrumental in expressing things by lines and colors."15 Japan's Independent Administrative Institution National Museum of Art shows 15 prints, in addition to this collection's print, in their database.16

While Merritt states that the works of Yasui "were reproduced as woodblock prints," the word "reproduced" suggesting fukusei-hanga, I've seen no examples of woodblock prints reproduced from his paintings.17 At least for the nine prints pictured below, along with this collection's print, they are original designs created by Yasui to be produced as woodblock prints by others, with his creative oversight.

Merritt goes on to discuss Yasui's prints in some detail, as follows:

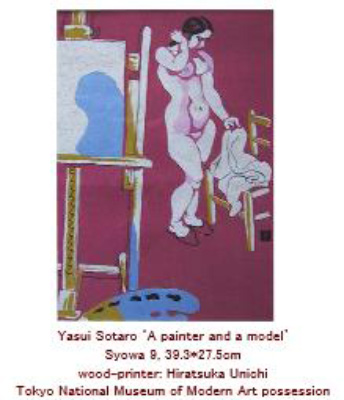

"In 1932 he sought the services of a sōsaku-hanga artist and skilled carver Hiratsuka Un’ichi, to makeblocks for two prints, Woman in Chairand Fruits, to be published by IshiharaRyūichi of Kyūryūdō. Hiratsuka, workingin close association with Yasui, carved the desired blocks, but Yasui soughtthe services of a regular artisan to carve the blocks for other prints to bepublished by Kyūryūdō and Katō Junji. Although he probably felt empathy for Hiratsuka as a creative artist,Yasui seems to have concluded that Hiratsuka’s carving, because of itsindividual uniqueness, detracted from his own expression."18

| Artist and His Model, 1934 The National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo (P01538) | Woman Leaning on a Chair, 1934 The National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo (P01521) | Early Summer, 1933 The National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo (P01523) |

| Landscape in the Boso Peninsula, 1932 (as titled by the The National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo) (P01539) Gaibo Fukei. View Outside a Studio Window Museum of Fine Arts, Boston (55.357) | Woman Listening to a Record, 1935 The National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo (P01541) Girl Listening to a Record Player, 1935 Museum of Fine Arts, Boston (55.80) | Fruits, 1934 (as titled by the The National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo) (P01522) Pineapple, grapes, pears and an orange. Arrangement on a white cloth against blue background Museum of Fine Arts, Boston (54.95) |

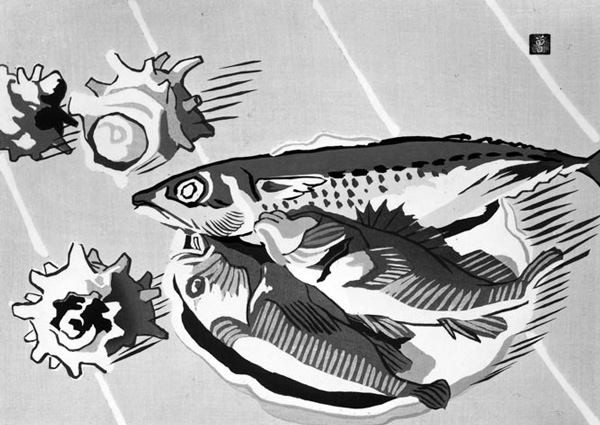

| Autumn on Lake Towada, 1935 The National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo (P01540) | Roses, 1934 The National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo (P01537) | Fishes and Snails, 1934 The National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo (P01525) |

2 Among the many Japanese artists who were in Paris during at least part of Yasui's sojourn were Wado Sanzō (1883-1968), Yamamoto Kanae (1882-1946), Mitsutani Kunishirō 1874-1936), Yunoki Hisata (1885-1970), Umehara Ryūzaburō (1888-1986), Kobayashi Mango (1870-1947) and Kuwashige Giichi (1883-1943) and Fujita Tsuguharu (aka Leonard Fujita, 1886–1968).

3 website of the Bridgestone Museum. http://www.bridgestone-museum.gr.jp/en/collection/artist75/

4 Paris in Japan: The Japanese Encounter with European Painting; Takashima, Rimer and Bolas, The Japan Foundation and Washington University, 1987, p. 114.

5 In 1912 several painters of theyounger Bunten group petitioned Kuroda [Seiki] for a separate section of the Bunten inwhich to exhibit paintings of the new Western art styles, since the nihonga [Japanese art]division had been granted such asection. Kuroda refused on the groundsthat there were “no new schools in yōga,for it was all representative of the new style.” Discouraged by the encounter, these youngerpainters joined in opposition to the official stand and in 1914 began their owngroup, called the Nika-kai (Second Division Group). The Nika-kai attracted several promisingnames through its declaration that “this exhibit is open to all who wish toparticipate, with the exception of those who have applied to the Bunten.” Ishii Hakutei, Tsuda Seifū, UmeharaRyūzaburō, Yamashita Shintarō, Kosugi Misei, Arishima Ikuma, Sakamoto Hanjirō,Minami Kunzō, and Yasui Sōtarō helped to stir interest in the Nika-kai bycompeting among themselves for newer, more original modes of expression, andthis sudden surge of creative experimentation was one event which set the toneof Western-style painting in the Taishō era. The three figures of most enduring reputation among these were SakamotoHanjirō, Umehara Ryūzaburō, and Yasui Sōtarō. [Source: Arts of Japan 6: Meiji Western Painting, MinoruHarada, Weatherhill/Shibundo, 1974, p. 124

6 op. cit., Paris inJapan, p. 114.

7 ibid.

8 op. cit. Bridgestone Museum

9 Inexorable Modernity: Japan's Grappling With Modernity in the Arts, Hiroshi Nara, Lexington Books, 2007, p. 54.

10 Umehara Ryūzaburō, another Western-style Kyoto artist and a friend of Yasui's from childhood.

12 Guide to Modern Japanese Woodblock Prints: 1900-1975, Helen Merritt, University of Hawaii Press, 1992,p. 186.

13 Thesystem of appointing Imperial Household Artists (Teishitsu Gigeiin) wasestablished in the Meiji period for the promotion of the arts and crafts inJapan. An appointment was for life and the artist was treated as an officialappointed by the emperor and granted a pension. In return, the artist wasordered to produce works of art and provide advice and suggestions as requestedby the director of the Imperial Household Museum (presently Tokyo NationalMuseum).

15 Japanese Wood-block Prints, Shizuya Fujikake, Japan Travel Bureau, 1938 revised 1949, p. 137.

16 http://search.artmuseums.go.jp/search_e/sakuhin_list.php?sakka=1612#

last revision: