View of Ikejiri, Setagaya, 1922

IHL Cat. #1954

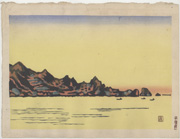

Mera Cape, Izu, 1929

IHL Cat. #1226

Nihonbashi, 1929

IHL Cat. #392

Peacock with Plum Blossoms, 1929

IHL Cat. #1677

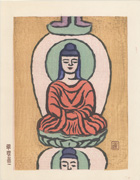

IHL Cat. #180

IHL Cat. #1336a

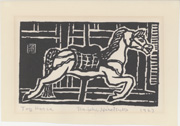

Toy Horse, 1963

IHL Cat. #647

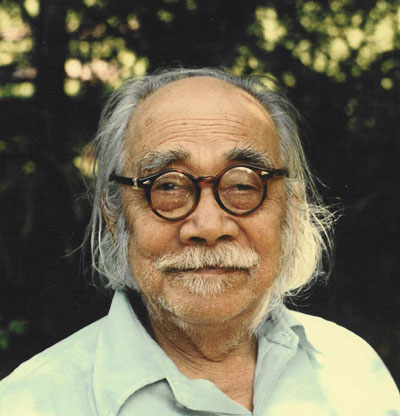

Hiratsuka Un'ichi 平塚運一 (1895-1997)Source: "Unichi Hiratsuka, Sosaku-Hanga Master" website of the grandchildren of the artist http://www.unichihiratsuka.com/and as footnoted. Hiratsuka was one of the two most prominent leaders of the sosaku hanga movement, along with Onchi Kōshirō (1891-1955). In 1935 Hiratsuka taught the first woodblock printing course at the Tokyo School of Fine Arts. He moved to Washington D.C. in 1962, and spent thirty three years in the States. While living in Washington DC, he was commissioned by three standing Presidents to carve woodblock prints of National Landmarks, which included the Lincoln Memorial, the Washington Monument and the Library of Congress which are in the collections of The National Gallery and Freer Gallery today. Hiratsuka was awarded the Order of Cultural Merit by the Japanese government in 1970. In 1991, the Hiratsuka Unichi Print Museum was opened in Suzaka, Naga Prefecture. He returned to Japan in 1994 for his final years. |

His prints have been described "as symbols of a unique symbiosis between the twentieth-century art of Japan and that of the West."1

1 Hiratsuka: Modern Master, Helen Merritt, et. al., Art Institute of Chicago, 2001

Biography

Hiratsuka's road to becoming a hanga artist is best told through his own words, as quoted by Oliver Statler in Modern Japanese Prints.1

I come from Matsue, the old town near the Japan Sea where Lafcadio Hearn lived and taught school. My grandfather was an architect of houses and temples and there were always carpenters around our place, so I grew up with a feeling for wood and tools. The first carving I became aware of was the work of the seal-makers, the men who make the big and little hand-stamps without which nothing in Japan can be authenticated. I started by carving Chinese characters, as they did, but I soon went on to pictures. That was the period when those avant-garde art magazines Myoji and Shirakaba were introducing the post-impressionists to Japan. I studied these magazines avidly, so my early influences were all Western.2

I hadn't really made up my mind to be an artist till, when I was eighteen, Ishii Hakutei (1882-1958) came to Matsue. I studied with him for the month he taught there, and when he praised one of my water colors, that did it. I waited until I was twenty-one and then I came to Tokyo and enrolled in the art school of Okada Saburosuke (1869-1939). Okada was a great academician and I stayed in his school for five or six years, but I felt much closer to Ishii, and it was to him that I kept going to show my work and get advice. He was really my teacher. I've never stopped learning from him.

Those were the days when the creative print [sosaku hanga] movement was being born. Kanae Yamamoto and Ishii were the heart of it, and when one day I told Ishii that I had always been interested in making prints, I hit on something he was deeply excited about. He insisted that the day of the creative print was not far off and urged me to study print-making seriously. On his advice I went to the artisan Bonkotsu Igami to study the technique of carving.

...Igami set me to learning how to carve the blocks for reproductions of traditional ukiyoe color prints. He made me work hard on difficult carving techniques like the hair on the face, and he forbade me to work on my own pictures. I had six months of this training, and then he told me I had the fundamentals and dismissed me to go my own way.

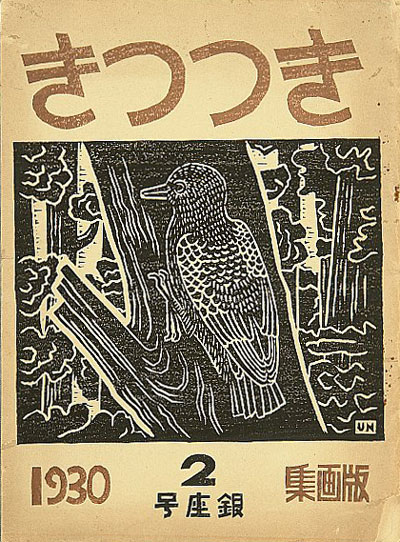

| By the mid-1920s Hiratsuka had emerged as one of the most active and influential artists in the sosaku hanga movement. He was the "practical leader" of the sosaku hanga movement while Onchi Kōshirō (1891-1955) was its "intellectual and spiritual leader."4 He founded and was active in many artists' organizations such as the Nikakai and later the Nihon Sosaku-Hanga Kyokai and the Kokugakai. (See the Glossary for information on these artist organizations.) In Tokyo he worked for a number of art and related magazines and throughout his career he was instrumental in publishing many small art magazines. He taught many young artists who "flocked to his studio for help and encouragement."5 His leadership role in the sosaku hanga movement was recognized through the spawning of a number of artist groups which called themselves Kitsutsuki (Woodpecker), after Hiratsuka's print Kitsutsuki was published in the magazine Hanga.6 In 1927 he published the book Hanga no giho (Print Techniques.) |

1 Modern Japanese Prints: An Art Reborn, Oliver Statler, Charles E. Tuttle Company, 1956, p. 36-37.

2 Speaking of the influence of Western art on his work Hiratsuka said "Western art gave me my technique but Japanese art gave me my approach." Ibid. p. 39.

4 Ibid. p. 200.

6 Ibid. p. 205.

Shin Tokyo yahakkei (One Hundred Views of Tokyo)

Source: Modern Japanese Woodblock Prints - The Early Years, Helen Merritt, University of Hawaii Press, 1998, p.276-278.

Hiratsuka recalls that this series was planned so that many aspects of Tokyo could be “remembered by people for a long time.”1

1 "Shin Tokyo Hyakkei: The Eastern Capital Revisited by the Modern Print Artists," James B. Austin from the magazine Ukiyo-e Art A Journal of the Japan Ukiyo-e Society, No. 14, 1966.

Teaching Activities

Source: Modern Japanese Woodblock Prints - The Early Years, Helen Merritt, University of Hawaii Press, 1998, p. 204, 208 and as footnoted.

Throughout the 1920s Hiratsuka taught workshops in many parts of Japan and also taught at Kanae Yamamoto's farm people's school1 in Shinshu. He taught the first print classes in 1935 at the Tokyo Art School and in 1943 he was hired by Peking National University of Art to teach the print arts (although he refused to work directly for the government during World War II.) After the war he set up his own school in Tokyo along with establishing the Matsue Arts and Crafts Institute in his hometown.2

Hiratsuka was also a collector and the influence, both physical and spiritual, of the things he collected is seen in his work. Originally intrigued by foreign textbooks which he collected at a young age, he expanded his collecting to Buddhist prints and rubbings, roof tiles, Judaica and bibles in various languages.

2 Hiratsuka: Modern Master, Helen Merritt, et. al., Art Institute of Chicago, 2001, p.14.

Black and White Prints

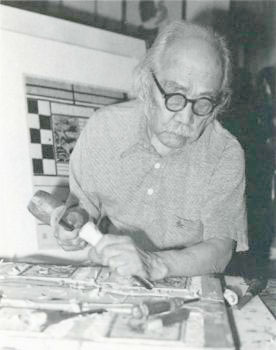

Hiratsuka carving, 1982 Hiratsuka carving, 1982 | Up until WWII, Hiratsuka produced both multi-color and black and white woodblock prints, but after WWII his production was almost entirely black and white prints. Hiratsuka believed black and white to be the "zenith of the art of picture printing" and it is the work he is most famous for. His black and white work has been called sculptural.1 "To me black and white have always been the most beautiful of colors. For some subjects I feel that I must go into other colors, but I know that generally my work weakens when I do. "With its special beauties, a black and white has special problems. To borrow musical terms, a black and white must have a rhythm of line and mass and a harmony of straight lines and curves. One of the great difficulties is to make the white space live.... The handling of white space is different in every one of my pictures." 2 His most famous carving technique is called tsukibori ("poking strokes"). With a small square-end chisel (aisuki), Hiratsuka rocked the blade side to side in short strokes, producing rough and jagged edges.3 |

Living in the United States

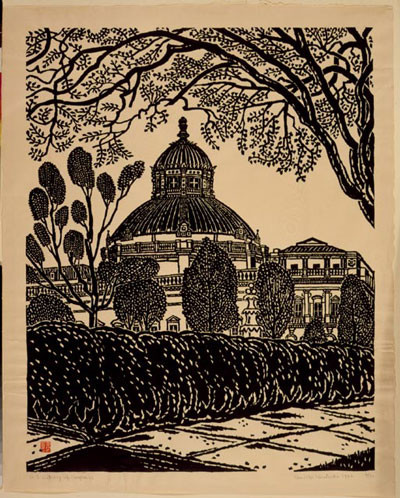

Library of Congress, Washington, D.C., 1966.

Woodblock print, 31 in. x 24 1/2 in.

Prints and Photographs Division (101)

(LC-USZC4-8509)

In 1970 the Japanese emperor awarded him the Order of Cultural Merit, which had never previously been awarded to a print artist and in 1977 Hiratsuka became the first artist ever to be awarded with the Order of the Sacred Treasure for "the quality of his art, the techniques he was able to pass along to his students and followers, and his accomplishments in promoting friendship between the United States and Japan."1

1 Hiratsuka: Modern Master, Helen Merritt, et. al., Art Institute of Chicago, 2001, p.19.

Return to Japan

While Hiratsuka often spoke of returning to Japan during the 33 years he spent in the U.S. it was not until late 1994 that he did return. A retrospective of his work in 1996 was staged at the Hitaki Ukiyo-e Museum in Yokohama and in 1991 the Hiratsuka Unichi Print Museum (http://www5.ocn.ne.jp/~su-bunka/hanga.htm) was established in the City of Suzaka in Nagano prefecture. Hiratsuka passed away on November 18, 1997 at the age of 102. His wife of 80 years, Teruno, passed away shortly thereafter.

Hiratsuka left a legacy of writings on the art of woodblock and hundreds of prints over 200 of which are in the collection of the Chicago Art Institute.

A Note on the Artist's Given Name

Hiratsuka's given name is seen as "Un'ichi", "Un-ichi" and "Unichi".

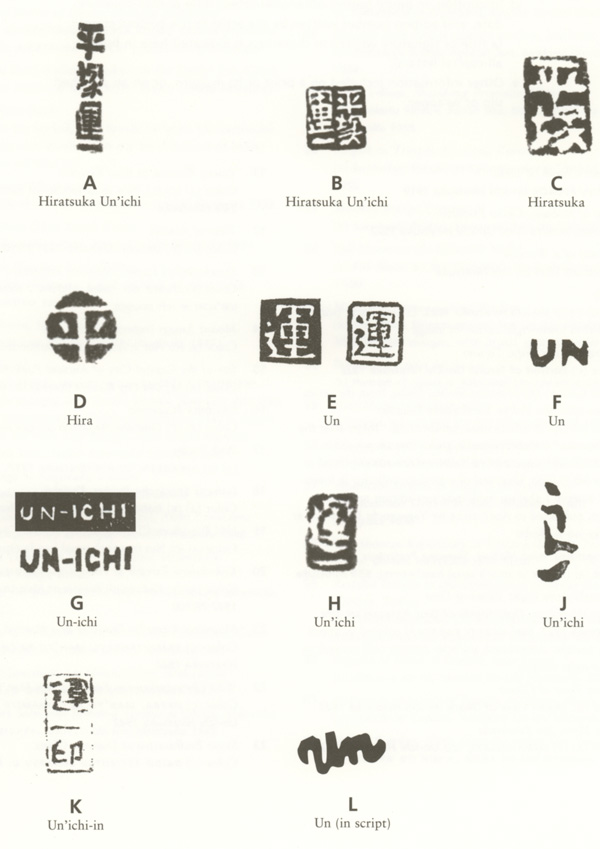

Seals and Signatures

Hiratsuka used various kanji and roman signatures. His seals may use one or more of the characters in his name. Sometimes the seals in red, brown or other colors were carved into the key block and sometimes they were stamped onto the print. Hiratsuka also used letters from the roman letter writing of his name. Common seals of the artist are shown below.1

1 Hiratsuka: Modern Master, Helen Merritt, et. al., Art Institute of Chicago, 2001, p. 117.

Notes on Editions

1 Modern Japanese Prints: An Art Reborn, Oliver Statler, Charles E. Tuttle Company, 1956, p. 41.

We also learned to understand his print numbering system. He omitted the number four, since the word for that number in Japanese, shi, sounds like the word for death. The word ku, meaning nine, has the same pronunciation as a Japanese word for "pain" and "suffering." Thus, the numbers on Hiratsuka's prints do not alwas indicate the actual edition that was printed.2

My father would make a number of prints at a time and allow them to dry. My mother matted his prints. Another of her jobs was to ask him to sign his name and affix seals and edition numbers on the finished and dried prints. The importance of signatures, titles in English, edition numbers, and dates had been impressed upon Japanese printmakers by Americans after World War II. My father strongly resented and resisted these new practices, much preferring to work on new prints than perform such boring chores. When forced to comply, he would play games with us by putting down any numbers he wished, such as 65/100 or 86/200, even though he rarely made more than a dozen or so of any specific print. Very stubborn and rebellious, he simply ignored our instructions to start with lower numbers and keep to smaller editions. After years of trying, my mother and I finally gave up on this issue.3

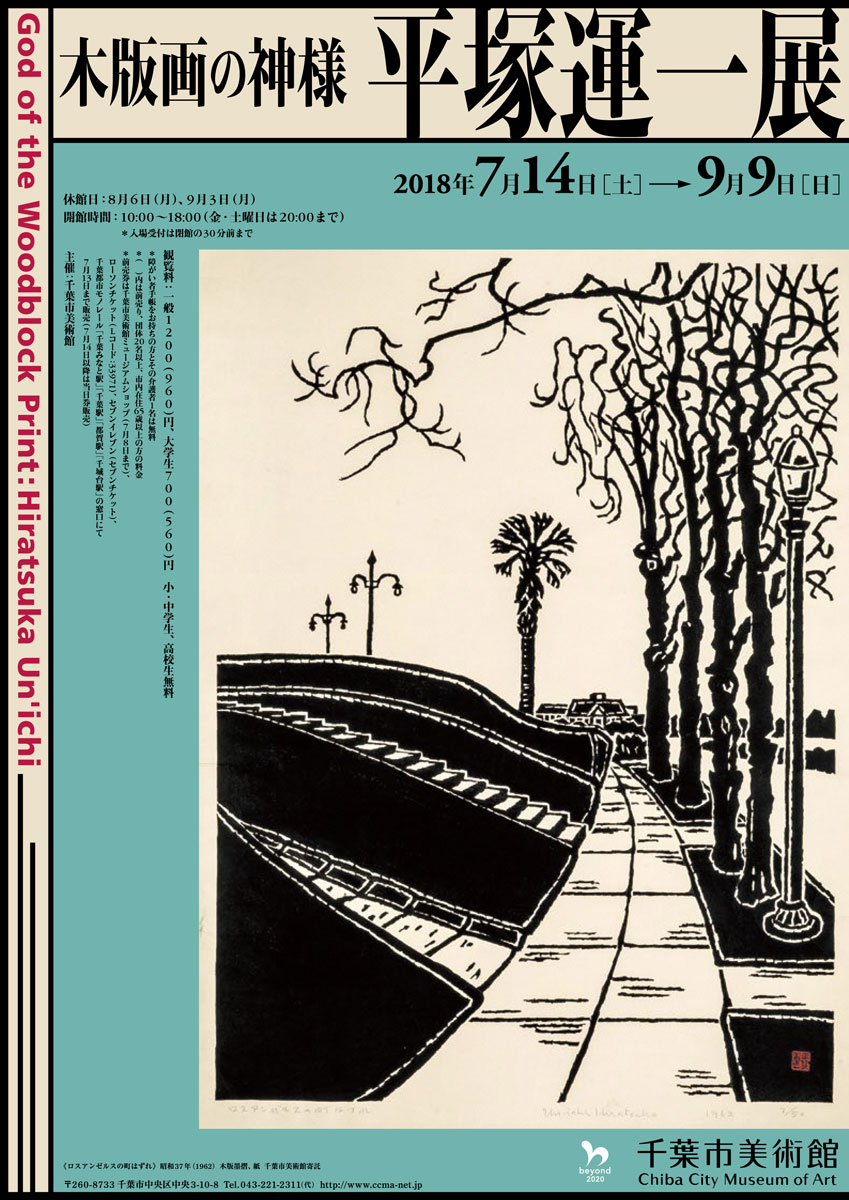

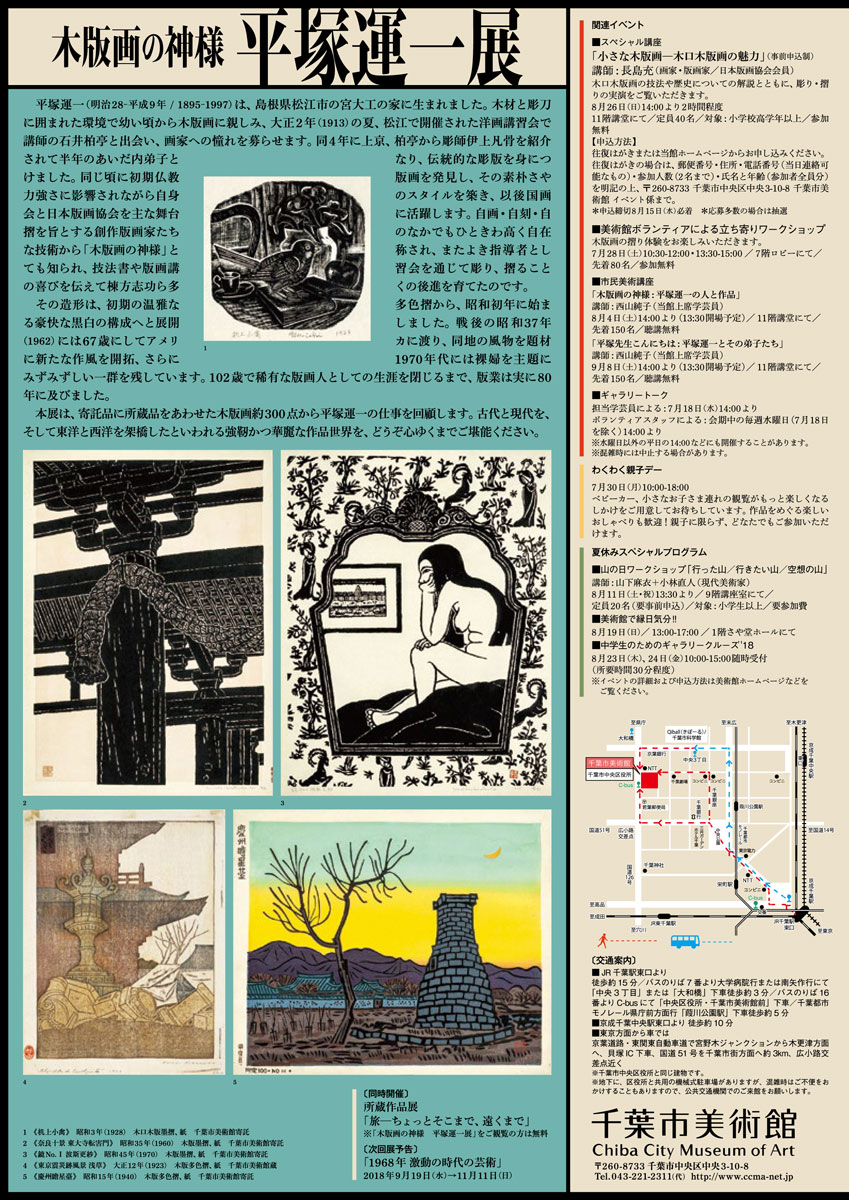

God of the Woodblock Print: Hiratsuka Un'ichi

July 14 - September 9, 2018

Hiratsuka Un’ichi

“Byôdôin Pondside”,

1960,

held in trust at

Chiba City Museum of ArtLeading artist of sôsaku hanga, creative prints in modern-era Japan, Hiratsuka Un’ichi (1895-1997) mastered all areas of the art of carving and printing woodblocks, and also exhibited rare talent as teacher of the techniques, which gave him the name “god of the woodblock print”. His 80-year long career in print-making will be here to evaluate through as many as 300 of his works housed in the collection combined with items held in trust. After a break of 20 years, this major retrospective exhibition is once again on display, tracing the magic of the vivid multi-colored printing that began in the Taishô Era (1912-26), to the new developments made post-war in powerful black-and-white composition.

Collections

Hiratsuka's works reside in collections worldwide including: Tokyo Museum of Modern Art; Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC; Boston Museum of Fine Arts; New York Metropolitan Museum; Rockefeller Foundation, New York; Library of Congress, Washington, DC, the British Museum, London and the Chicago Art Institute; Honolulu Academy of Arts; Cincinnati Art Museum; Carnegie Museum of Art, Pittsburgh.

Literature and Websites

Hiratsuka: Modern Master, Helen Merritt, et. al., Art Institute of Chicago, 2001

Modern Japanese Prints: An Art Reborn, Oliver Statler, Charles E. Tuttle Company, 1956

Modern Japanese Woodblock Prints - The Early Years, Helen Merritt, University of Hawaii Press, 1998

Art Institute of Chicago online collection showing over 200 of the artist's works http://www.artic.edu/aic/collections/search/citi/artist%3Ahiratsuka

"Unichi Hiratsuka, Sosaku-Hanga Master" website of the grandchildren of the artist http://www.unichihiratsuka.com/

http://blog.livedoor.jp/aa3454/archives/76977715.html [a blog with images of works in the exhibition God of the Woodblock Print: Hiratsukia Un'ichi 木版画の神様 平塚運一展 held at the Chiba City Museum of Art]

last revision:12/13/2018