About This Print

In this print, originally created for volume three of the six volume elementary school morals textbook Nishikie Shūshindan ("Brocade Pictures for Moral Education"), Yoshitoshi portrays the widow ShihinoShinasa caring for her own children along with the children of her husband's concubine without favor. After her husband's death, she vowed to remain chaste thereby fulfilling the li of a woman.

For more information about shūshindan (moral education) and the prints included in, or associated with, these textbooks see the article Brocade Pictures for Moral Education on this site.

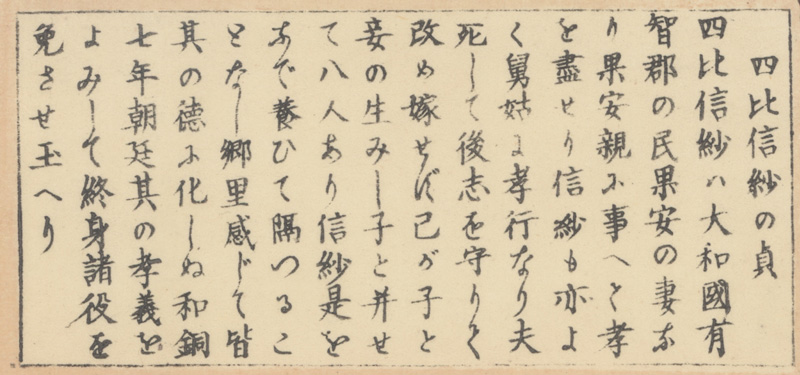

Explanatory Cartouche and Summary of the Explanation

According to the Shoku Nihongi, it is recounted that ShihinoShinasa who lived in Uchi-gun (modern day Gojo-shi) was the wife of Uji no Hatayasu and served her in-laws with filial piety. After the death of her husband, she raised eight small children including the child of her husband's mistress/concubine without showing favoritism to any so that in the eleventh month of the year 714, she was exempted from a lifetime of labor/taxation*. [*shushin kaeki is an archaic term referring to a form of taxation accrued over a lifetime that was paid back to the state through labor].

Confucian Good Government and Li

Source: Ritsuryō Confucianism" Author(s): Charles Holcombe Source: Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies, Vol. 57, No. 2 (Dec., 1997), pp. 543-573 Published by: Harvard-Yenching Institute Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/2719487

For Confucians, good government meant not effective government, but one that was literally, morally, good. The main purpose of state gestures in the direction of public welfare was to demonstrate imperial virtue-which, by itself, constituted good government from a Confucian perspective, sufficient to move heaven itself, and generate peace and fair weather. Beyond demonstrating their own virtue, a further obligation of Confucian monarchs was the promotion of virtue among their subjects. The ritsuryō state was not overly concerned with the provision of consumer services: for the ruler and people to all be virtuous alike was assumed to constitute the height of statecraft. Thus, in 708, at the beginning of a new reign period, Empress Genmei proclaimed a general amnesty, and declared: "Mark the dwellings of filial sons, obedient grandchildren, widowers who do not remarry, and chaste women, and make them tax exempt for three years."

Among the characteristically Confucian values promoted by the court was that of the chaste widow, who refused to remarry after her husband's death. In 712, for example, the Emperor commended Lady lehara, widow of the Minister of the Left Tajihi Shima, and Lady Ki, widow of Minister of the Right Otomo Miyuki, observing that "both, when their husbands were alive, encouraged them in the Tao of the state, and when their husbands were gone, held firm in their intention to [be buried in] the same grave [i.e., not remarry]. When we contemplate their chastity [Ch: chen-chieh, J: teisetsu], we are deeply moved. These two people should each be granted a village of fifty households."

In 714 tax and labor service obligations were permanently canceled for the woman Shinasa, because she "was renowned for her filial service to her in-laws. After her husband died, she stuck to her purpose for many years. She brought up, altogether, eight children of her own and [her late husband's] concubines without making distinctions between them. In serving her in-laws she fulfilled the li of a woman, and was the wonder of her community."

The Illustrations and Prints in the Textbooks

Yoshitoshi designed twelve aiban-size color prints along with all thirty-three black and white illustrations for the six volumes of Brocade Prints for Moral Obligations, issued between March 1882 and July 1884. Between one and three of Yositoshi's color prints were inserted, each print being folded in half, in the front of each book.

Many of Yoshitoshi's black and white illustrations later became the basis of single-sheet oban-size color prints designed by a number of his students, as is explained in the notes to the print titled Tame/reject wildness/violence with the sincere spirit of a filial child (IHL Cat. #430) by the artist Kobayashi Toshimitsu (active 1876–1904), a student of Yoshitoshi's.

Most, if not all, of the twelve color prints Yoshitoshi designed for the textbooks were reprinted in 1888 and sold as individual sheets.

A Little About the Publisher

Source: Principle, Practice, and the Politics of Educational Reform in Meiji Japan, Mark Elwood Lincicome, University of Hawaii Press, 1995, p. 81-82.

Tsuji Keiji, an alumnus of the Tokyo Normal School and the author of several textbooks, was intensely committed to the dissemination of developmental education. To that end, in 1882 he established his own publishing house, the Fukyūsha (fukyū means “disseminate”), which published numerous books incorporating the principles of developmental education.

Print Details

| IHL Catalog | #925 |

| Title | The Chastity of ShihinoShinasa 四比信紗の貞 |

| Series | Nishikie Shūshindan 錦絵修身談 (Brocade Pictures for Moral Education; also seen translated as Instructive Stories in Color Prints and Color Prints of Stories for Moral Education) The print was created for Volume 3 (巻三) of the textbooks. |

| Artist | Tsukioka Yoshitoshi (1839-1892) |

| Signature |  |

| Seal | 大蘇 Taiso in seal script |

| Date | 1882 |

| Publisher | 普及舎 辻敬之 Tsuji Keiji of Fukyūsha |

| Carver | |

| Impression | good |

| Colors | excellent |

| Condition | good - center fold from insertion in book |

| Genre | kyōiku nishikie |

| Miscellaneous | |

| Format | horizontal aiban folded in half for insertion into textbook |

| H x W Paper | 8 13/16 x 10 9/16 in. (22.4 x 26.8 cm) |

| H x W Image | 8 1/4 x 10 1/16 in. (21 x 25.6 cm) |

| Collections This Print | |

| Reference Literature | Yoshitoshi, Masterpieces from the Ed Freis Collection, Chris Uhlenbeck and Amy Reigle Newland, Hotei Publishing, 2011, p. 155, no. 27. |