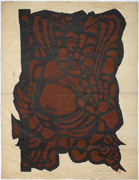

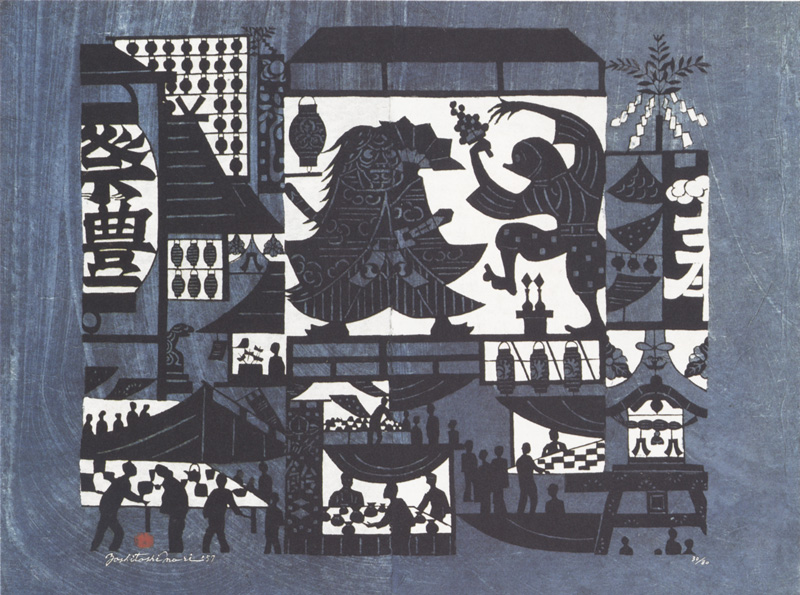

Niō Guardian (Red), 1960

IHL Cat. #1682

[donated to the Portland Art Museum]

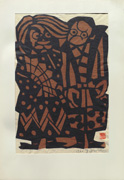

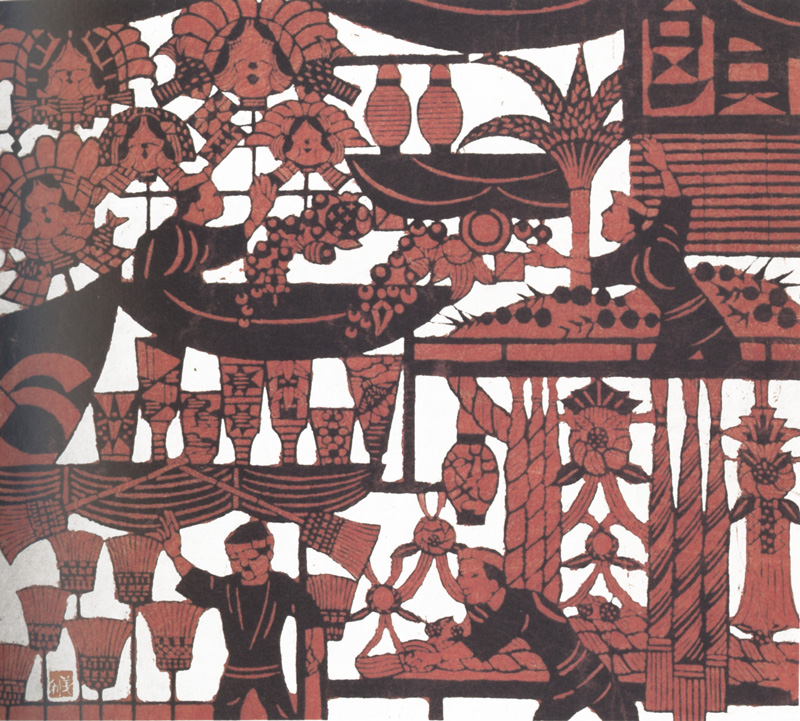

Kagura no Dōke (Kagura Buffoonery), 1960

IHL Cat. #1336c

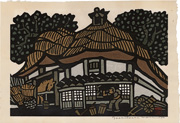

Portable Shrine Festival,

c. 1960

IHL Cat. #1017

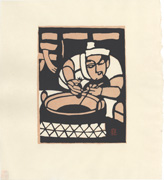

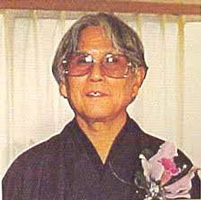

Blacksmith, 1970

IHL Cat. #2006

Gorō,

c. 1970-1985

IHL Cat. #1477

Tempura Chef, 1988

IHL Cat. #1192

As his print work developed and became a vehicle for artistic expression rather than simply “craft”, he came in conflict with leaders of the mingei movement, Yanagi Sōetsu 柳宗悦 (1889-1961)and Serizawa Keisuke 芹沢銈介 (1895-1984), and he would abandon that movement to focus on his artistic stencil prints. He would become known as a major figure in the sōsaku hanga (creative print) movement.

In addition to his stencil prints he created paintings on glass, calligraphic works and a small number woodblock prints. His prints have been shown throughout the United States and internationally.

Mori’s art dramatizes not only the subject matter itself but also the abstract relationships of space, color, and line, which strengthen the total expression.

- Japanese Prints Today: Tradition with Innovation, Margaret K. Johnson, Dale K. Hilton, Shufunotomo Co., Ltd., 1980,p. 58.

Biography

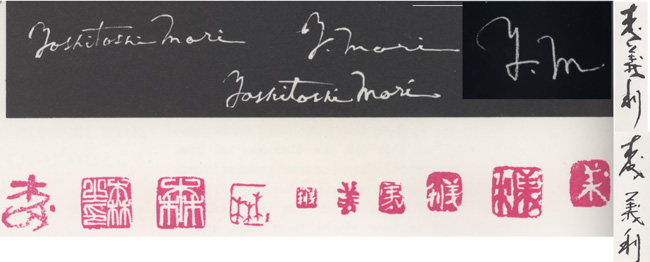

Mori Yoshitoshi (October 31, 1898-May 29, 1992)) 森義利Sources: Mori Yoshitoshi Kappa-Ban, Abe Setsuko, et. al.,Organizing Committee for the Mori Yoshitoshi Exhibition on 1stJanuary, 1985, 1985, p. 14-23 and as footnoted.

Early Life

Born on October 31, 1898 in the home of his grandfather Mori Genjirō located in Nihonbashi, Tokyo, he was the first born son of Yonejirō and Mori Yone. His maternal aunt gave him the name Yoshitoshi. At the age of four his father left home and the family’s wholesale fish business went bankrupt, forcing him, his mother, brother and grandfather to move into his aunt’s house in Nihonbashi. Traditional music was part of his new household, with a grand uncle heading a school for wooden flute (yokubue) and his mother and aunt teaching nagauta (lyrical songs with shamisen, originating with kabuki). In 1906, at the age of eight, one year after entering elementary school, Yoshitoshi’s mother remarried and moved in with her husband, leaving Yoshitoshi to continue living with his aunt. Also in this year the eight year old Yoshitoshi suffered a shock when he was the first to find his dead grandfather who had committed harakiri, distraught over the failure of the family business.

First Artistic Stirrings

At the age of thirteen he was forced to leave his private higher elementary school and start working odd jobs because of the death of his uncle and resulting money troubles. This is also the year that he became interested in the actor prints of Utagawa Toyokuni (1769-1825), the illustrated books of Tsukioka Yoshitoshi (1839-1892) and Mizuno Toshikata (1866-1908), and the theater prints of Ogata Gekkō (1859-1920) kept by his mother’s new husband. It was also about this age that he began sketching.

After working briefly at a dyeing workshop of a family friend, in 1925 he set up his own workshop, drawing kimono patterns and dyeing, and became a member of Monyō Renmei (Association of Kimono Pattern Craftsmen). Over the next few years his business and reputation flourished despite the economic downturn caused by the Great Depression.

Marriage and Family, Folkcraft and the Pacific War

In 1928 at the age of thirty he married twenty-four year old Shimizu Iku and six years later his first daughter Eiko was born, followed two years later by his daughter Kozue. With his reputation growing as a textile designer he would embrace the mingei folk craft movement, often visiting the Japan Folkcraft Museum and the founder of the folkcraft movement Yanagi Sōetsu (1889-1961) for study and assistance. He would also visit the famous textile designer and stencil-dyer (named Living National Treasure in 1956), Serizawa Keisuke (1895-1984).2 In 1940 he met print artists Munakata Shikō (1903-1975) and Sasajima Kihei (1906-1993).

In 1942 at the age of forty-five, his 3rd daughter Ayako was born, as the Pacific War raged. Because of wartime prohibitions on luxury items, life was difficult for silk-dyeing artists. Mori lost his apprentices to the draft and as now chairman of the Monyō Renmei, assisted members in dealing with wartime shortages and restrictions.

1944 was a particularly hard year as air raids on Tokyo intensified. His wife became very ill that year and Yoshitioshi “wore himself out with worrying about his wife’s health and caring for this three small children.” However, he was granted permission that year to make and sell dyed kimonos, signing his work with the craftsman name of Kōshū.

Postwar YearsThe early post-war years saw his textile work gain increasing fame and his winning of several awards at exhibitions. In 1949 he built his home where he would live out his life in Nihonbashi, Chūōku and became an associate member of the craft section of the Kokugakai (National Picture Association).

Continuing to win praise for his work, Yoshitoshi finally dedicated himself to prints in 1960 at the age of sixty-two, with the signing of a two-year contract with Tokyo’s Nihonbashi Gallery to exclusively show his work. 1962 saw his work Kagura no doke (Comic Shrine Dancers) included in James Michener’s seminal 1962 portfolio of prints and accompanying book The Modern Japanese Print an Appreciation, further increasing his exposure outside Japan.3

In 1962 as his work became less craft-like and more artistic, tensions developed with Serizawa over the differences between crafts and art and he left the craftsmen’s division of Kokugakai. He would leave the Nihon Banga in in 1964, remaining free of professional associations until 1982 when he was recommended for membership in the Japan Print Association. Through the 1960s he continued to show his prints extensively, including numerous exhibitions in the United States.

Rediscovering His RootsAt the age of seventy-two, in 1970, Yoshitoshi visited Europe. This proved to be a formative event in his older years credited with his refocusing his work on classic Japanese subjects such as The Tale of Genji and The Tale of Heiki, turning out two large series of prints based upon these two epic works of Japanese prose.

Through the 1970s Yoshitoshi designed hundreds of prints culminating, at the age of eighty-one, in a 1979 solo show at the Honolulu Museum of Art, the first living Japanese artist to be so honored. Suffering from failing eyesight in his late seventies, cataract surgery in 1981 allowed him to continue his print work. In 1984he was presented with an honorary Ph. D. in Art from the University of Maryland, the first Japanese artist to be so honored and in 1991 he was honored by the Tokyo Metropolitan Government. He continued working until his death on May 29, 1992, at the end of his final solo show at the Wako Gallery Tokyo.

1 His graduation from the Japanese-style painting division of Kawabata Gagakkō is not mentioned in Mori Yoshitoshi Kappa-Ban, but several other sources including Merritt's Guide to Modern Japanese Woodblock Prints, p. 95 and Roberts' Dictionary of Japanese Artists, p. 112 do mention it.

2 Serizawa would also apply the technique of traditional stencil-dyeing (katazone) to paper.

3 The Modern Japanese Print: An Appreciation, James A. Michener, with Ten Original Prints by Hiratsuka Un'Ichi, Maekawa Sempan, Mori Yoshitoshi, Watanabe Sadao, Kinoshita Tomio, Shima Tamami, Azechi Umetaro, Iwami Reika, Yoshida Masaji, Maki Haku; Rutland, Charles E. Tuttle Company, 1962.

Source: website of John Fiorillo's http://viewingjapaneseprints.net/texts/topictexts/artist_varia_topics/stencil3.html

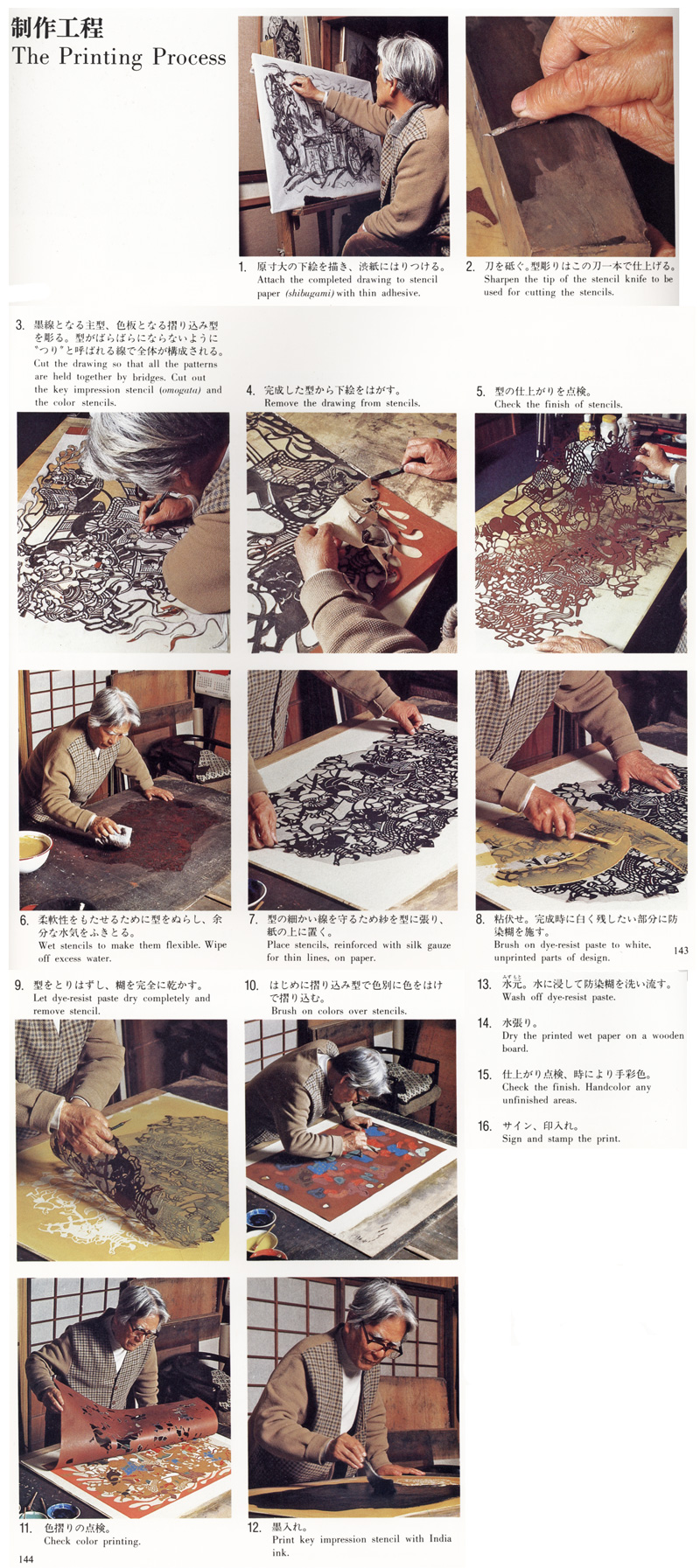

Kappazuri (stencil printing) is similar to katazome (stencil dying), which is said to have originated in Okinawa. The paper most widely used in Japan for stencil printing is called shibugami, made from several layers of kozō paper laminated with persimmon tannin. The sheets are dried and smoke-cured to strengthen them and make them flexible and waterproof. Once the artist makes a drawing, it is fixed to the shibugami with a thin adhesive. The basic pattern is then carved into a "key impression" stencil (the equivalent to the key block in woodblock printing) called the omogata. If colors will also be used for the final design, separate stencils are sometimes cut for each color. If the stencil pattern has thin lines they can be reinforced with silk gauze, which still allow for uniform printing of colors. The first stage of the printing process involves the application and drying of a dye-resist paste to cover all the portions of the design to be left unprinted by the design. The patterns and colors can then be brushed over the stencil while affecting only those areas without resist paste. Typically the first colors printed are the lighter areas so that darker colors can be overprinted. After all the colors are printed and dried, the key impression stencil is finally used to print the key design over all the previous colors. The dye resist paste is then washed off (called mizumoto, "to wash by water") and the paper is dried on a wood board.

The Printing Process

Source: Scanned from Mori Yoshitoshi Kappa-Ban, Abe Setsuko, et. al., Organizing Committee for the Mori Yoshitoshi Exhibition on 1st January, 1985, 1985, p. 142-144

Collections

Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo; Museum of Modern Art, Kamakura; New York Museum of Modern Art; Barcelona Art Museum, Berlin National Museum; The British Museum; Detroit Institute of Art; Los Angeles County Museum of Art; Art Institute of Chicago; Museum of Fine Arts, Boston; Portland Art Museum, Honolulu Academy of Art; Fine Art Museums of San Francisco and the official residence of the Prime Minister of Japan among many others.