History 456

Revolutionary and Early National America

Matthew Dennis

University of Oregon

Winter 2004 Course Syllabus

CRN 25266

Mondays and Wednesdays, 8:30-9:50, 111 Lillis Hall.

Class: M, W 8:30-9:50.

Matthew

Dennis, History, 357 McKenzie

Hall; mjdennis@darkwing.uoregon.edu

Office hours: M 2-3:30, W 10-11:30.

Course Description

This course on Revolutionary and Early National America will adopt a case-study approach to assess the early national origins of American culture, society, and politics.

• What did “Founding Fathers” mean when they declared that “all men are created equal”? What was the purpose of the Declaration of Independence, and how did it become as much an event as a document? Has its meaning evolved since 1776?

• To what extent was the War for Independence a revolutionary war? Who fought, why, and what were the consequences of warfare in American communities? What was the relationship between the war and the American Revolution?

• How and to what extent did the United States Constitution settle the Revolution? How did it create a “more perfect union”? What were (and are) its legacies?

• How did African Americans, particularly free blacks in the urban North, experience Independence once it was achieved in the Revolution? If the Revolution ended slavery north of the Mason-Dixon line , why didn't the liberatationist logic of the new nation abolish slavery throughout the republic?

• Was early national America a place of Reason or one of sentimentality? Was it a world filled with optimism or pessimism about the potential success of a republican society? And where did women fit into that world, public and private? How was early national America “gendered,” and what has been the legacy of that prescribed order of “Founding Fathers,” “Republican Mothers,” “rakes,” and “coquettes”?

• What did it mean to be an “American”? What was the nature of national identity in the Early Republic ? How did nationalism emerge, and how was it practiced? How and why did early national scientists and humanists imagine that America was “Nature's Nation”? Did the American landscape define America 's unique identity, and if so where did Native Americans fit into nationalist histories and plans?

We will face these and other questions, focusing attention on five two-week units, during the term.

Format and Requirements

This course will combine lecture with discussion, often weaving the two together to make class sessions interactive. Brief lectures will generally build upon, not simply recapitulate, readings. Students are responsible for completing reading and written assignments by the time indicated on the syllabus. These assignments will often provide the basis for class activity; students are expected to attend all class meetings and participate actively. Except in extraordinary circumstances, no work will be accepted late. Students must complete all assignments in order to pass the course. Grades will be assigned according to students' performance on the following:

- quality of class participation (25%).

- 10 short (approx. 500 words) essays (one per week) (75%).

- There will be no exams.

Academic integrity is important. I will hold all students to the UO “Standards of Conduct.” Plagiarism will not be tolerated; all work must be your own, written for this class.

Readings include five required books:

• Richard D. Brown, ed., Major Problems in the Era of the American Revolution , 2d ed. ( Boston : Houghton Mifflin, 2000).

• Edward Countryman, ed., What Did the Constitution Mean to Early Americans? (Boston: Bedford/St. Martin, 1999).

• Eve Kornfeld, ed., Creating an American Culture, 1775-1800 ( Boston : Bedford/St. Martin, 2000).

• Gary B. Nash, Race and Revolution (Madison, Wis.: Madison House, 1990).

• The Coquette (1797), a novel by Hannah Webster Foster, ed. Carla Mulford (New York: Penguin, 1996).

These books are available at the University of Oregon Bookstore . Additional primary source readings will be available on the web.

Unit 1: Declaring Independence

This

unit will examine the Declaration of Independence—one of the

United States’ sacred texts—as an event as well as a

document. What were the Declaration’s origins? What did the

document "declare"? How was it "published," that is, in the eighteenth

-century sense of the word, publicized? Indeed, why do

some scholar see it as much a performance as a text? How and why has

the meaning of the Declaration changed since 1776?

This

unit will examine the Declaration of Independence—one of the

United States’ sacred texts—as an event as well as a

document. What were the Declaration’s origins? What did the

document "declare"? How was it "published," that is, in the eighteenth

-century sense of the word, publicized? Indeed, why do

some scholar see it as much a performance as a text? How and why has

the meaning of the Declaration changed since 1776?

January 5 (M)—Introduction.

Reading: "Declaration

of Independence";

runaway

slave notice (web).

January 7 (W)—"Declaring

Independence": the immediate context, purpose, and meanings of the

text.

Reading: Brown, Major Problems, 138-72.

Essay Assignment: In no more than two typed paged (approximately 500 words at most) compare and contrast the first two paragraphs of the Declaration of Independence with the rest of the document. How do these sections compare in terms of purpose, language, tone, and impact? Due in class Wednesday, January 7.

January 12: Origins of the Revolutionary Movement. “Declaring Independence ”: the Declaration as event and performance.

Reading : Brown, Major Problems , 47-69, 98-118, 128-36, 171-88.

January 14: Shifting Meaning and Sanctification of the Declaration.

Reading: Brown, Major Problems , 258-59, 261-62, 294-95; additional “Re-Declarations”: Frederick Douglass, Daniel

De Leon (1895); international

translations

of the Declaration

(web).

Essay Assignment: In a short essay (2 pages, approximately 500 words), compare and contrast the Declaration of Independence and the Gettysburg Address, focusing particular attentioin on ways the Declaration's noble ideas have been reworked and developed since 1776. Due in class January 14.

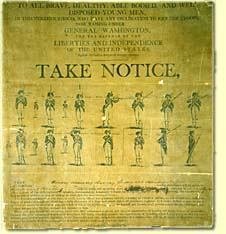

Unit 2: The War for Independence/Revolutionary War

It is worth noting that the American Revolution was hardly a sanitized, bloodless event; it was a war that cost the lives of thousands, destroyed and expropriated great amounts of property, and profoundly unsettled those who lived through it. This unit will examine the war, studying its origins, consequences, and effects, not only (or primarily) in military terms but to understand its social and political history. Was the war gendered? Was it fought for home rule or to determine who should rule at home? Was it a civil war? Was this anti-colonial war fought also to promote the colonial ambitions of the new nation? How did it affect American Indians? Did the war and military service alter social conditions in America ? Through readings, discussion, and film, we will probe these questions.

It is worth noting that the American Revolution was hardly a sanitized, bloodless event; it was a war that cost the lives of thousands, destroyed and expropriated great amounts of property, and profoundly unsettled those who lived through it. This unit will examine the war, studying its origins, consequences, and effects, not only (or primarily) in military terms but to understand its social and political history. Was the war gendered? Was it fought for home rule or to determine who should rule at home? Was it a civil war? Was this anti-colonial war fought also to promote the colonial ambitions of the new nation? How did it affect American Indians? Did the war and military service alter social conditions in America ? Through readings, discussion, and film, we will probe these questions.

Week 3

January 19: Martin Luther King, Jr. Birthday Holiday . No Class.

January 21: The War for Independence .

Reading : Brown, Major Problems , 189-255. Substitute this essay, The Iroquois and the Revolution, for pp. 238-47.

Essay Assignment: An image of citizen-soldiers firing upon British redcoats from behind stonewalls near Lexington and Concord often dominates representations of the Revolutionary War. How accurate is this image, and what role did militias actually play in the war? Write a short essay (approximately 500 words) that assesses the role and implications of militias in the Revolution. Due in class January 21.

Week 4

January 26: War as Revolution?

Reading : Brown, Major Problems , 256-86, 311-40.

Mary Silliman's War (a film). Mary Silliman's War introduction and questions.

Essay Assignment: Assess the film, Mary Silliman's War , as history . Write an essay (approximately 500 words) that evaluates the film's ability to convey historical “truths.” What does the film teaches us, and how do such lessons compare and contrast to those of conventional historical texts? Due in class January 28.

Unit 3: United States Constitution—"A More Perfect Union"?

If

the American Revolution began on April 19, 1775 at Lexington and

Concord, when did it end—with the Treaty of Paris (1783), with

the drafting and ratification of the Constitution (1787-88), with the

War of 1812? Various historians might answer differently—indeed

some might argue that it is still going on. The War for Independence

was a negative act; it severed the colonies’ ties with Great

Britain and declared that the several states were independent. But

what did that mean? How would Americans make sense of their struggle,

bring order to their new polity, and create a new government, or

governments? The United States Constitution is certainly central to

America’s revolutionary settlement. This unit probes its

origins, meanings, and implications, not only in the early national

period but into the present day.

If

the American Revolution began on April 19, 1775 at Lexington and

Concord, when did it end—with the Treaty of Paris (1783), with

the drafting and ratification of the Constitution (1787-88), with the

War of 1812? Various historians might answer differently—indeed

some might argue that it is still going on. The War for Independence

was a negative act; it severed the colonies’ ties with Great

Britain and declared that the several states were independent. But

what did that mean? How would Americans make sense of their struggle,

bring order to their new polity, and create a new government, or

governments? The United States Constitution is certainly central to

America’s revolutionary settlement. This unit probes its

origins, meanings, and implications, not only in the early national

period but into the present day.

February 2: Settling the Revolution: the Articles of Confederation

and "the united states of America."

February 2: Settling the Revolution: the Articles of Confederation

and "the united states of America."

Reading: Brown, Major Problems, 341-88; Countryman ,

3-29.

February 4: Settling the Revolution:

the Constitution.

Reading: Brown, Major Problems, 389-438; Countryman,

31-90.

Essay Assignment: Write a short essay that assesses the Constitution as an extension of the revolutionary movement. Did the new frame of government represent a realization of the movement's revolutionary trends, a reaction against them, or something in-between? Due in class February 4.

February 9: Nationalism, States, Sections.

Reading : Brown, Major Problems , 439-82; Countryman, Constitution , 91-111.

February 11: Rights, Legacies.

Reading : Brown, Major Problems , 483-51; Countryman, Constitution , 112-63.

Essay Assignment: Write a short essay (approximately 500 words) that treats a contemporary constitutional issue (e.g., the Patriot Act, gun control, war powers, Pledge of Allegiance, etc.) in the historical perspective of the early national period. Analyze specifically how or why an understanding of the creation and early development of the Constitution helps inform us about that issue or controversy.

Due in class February 11.

Unit 4: Slavery and Emancipation in the New Republic

This

unit explores the Revolution’s "contagion of liberty": the

implications of revolutionary ideals and circumstances for African

Americans, especially in the North where slavery was immediately or

gradually abolished. Readings and discussions will probe the meaning

of "freedom," "equality," and "liberty"; consider early national

black experience in northern seaboard cities; assess the issue of

race; and ask, not merely why was slavery abolished in the North? but

why it was institutionalized in the United States Constitution, and

why it continued—indeed expanded—in the South?

This

unit explores the Revolution’s "contagion of liberty": the

implications of revolutionary ideals and circumstances for African

Americans, especially in the North where slavery was immediately or

gradually abolished. Readings and discussions will probe the meaning

of "freedom," "equality," and "liberty"; consider early national

black experience in northern seaboard cities; assess the issue of

race; and ask, not merely why was slavery abolished in the North? but

why it was institutionalized in the United States Constitution, and

why it continued—indeed expanded—in the South?

Absolom Jones

February 16: Slavery, Revolution,

and the "Contagions" of Liberty.

Reading: chapter 1 documents in Nash, Race and Revolution,

91-131; plus documents pp. 167-76.

February 18: Abolition and Race in

the Early Republic.

Reading: Nash, Race and Revolution, 3-55, and chapter 2

documents, 132-65; Jefferson,

Notes on

the State of Virginia,

Queries XIV and XVIII (web).

Essay Assignment: Write a short essay (approximately 500 words) that assesses the nature and impact of abolitionist thought in the early republic. Make specific reference to the documents. Due in class February 18.

February 23: Black Americans, White

Republic, Yellow Fever.

Reading: Nash, Race and Revolution, 57-87, and chapter 3

documents, 177-201; Banneker-Jefferson correspondence (web); Charles

Brockden Brown, Arthur

Mervyn, chapter 16 (web);

Carey, Short

Account of the Malignant Fever,

excerpts (13-28, 65-68, 83-92) (web).

February 25: African Nationalism in

the early American Republic.

Read: sermons by Prince

Hall, Richard

Allen, and Absolom

Jones (web).

Essay Assignment: Write a short essay (approximately 500 words) that uses the writings of Prince Hall, Richard Allen and Absalom Jones, James Forten, and George Lawrence to assess the terms of African American claims for civil and political rights in the early American Republic . What rights did blacks claim, and on what basis did they claim them? Due in class February 25.

Unit 5: Gender, Sensibility, and American Culture in the New Republic of Letters

What sort of country would the United States become? What did it mean to be an “American”? Could the new American republic endure, particularly given its diversity and divisions? American intellectuals believed that national unity and survival required the creation of a vital national culture and identity, through the cultivation of a new American language, literature, mythology, art and iconography, and educational system.

What sort of country would the United States become? What did it mean to be an “American”? Could the new American republic endure, particularly given its diversity and divisions? American intellectuals believed that national unity and survival required the creation of a vital national culture and identity, through the cultivation of a new American language, literature, mythology, art and iconography, and educational system.

American nationalism was gendered. The Revolution had offered contradictory opportunities and sent mixed messages to American women. On the one hand, women were critical to the war effort; as such, they assumed a new, public role in social and political life, especially as a force for virtue in the new republic. On the other hand, older prescriptions against women in public life—and the equation of “public women” and prostitutes—persisted, and law and custom continued to subordinate and constrain women as daughters or wives. If new educational opportunities emerged for women, there were few legitimate outlets for women's energies and talents. Women like Hannah Webster Foster reflected the ambiguities of gender for women in the new nation. Would—should—the new republic be a place of female as well as male freedom and liberty? Was America a place of rationality and reason (gendered male) or feeling and sensibility (gendered female)? Through Foster's novel The Coquette , and through the literary and artistic representations of other early national writers and painters, we will probe the social and cultural world of early national America , its gendered implications, and the ways that this world was constituted through print and image.

Week 9

March 1: Creating an American Culture.

Reading : Kornfeld, Creating an American Culture , 3-109; Foster, The Coquette , letters 1-29.

March 3: Women and Men in the Early Republic.

Reading : Brown, Major Problems , 287-310; Kornfeld, American Culture , 110-20, 127-38; The Coquette , letters 30-53.

Essay Assignment: John Adams wrote, “without national Morality a Republican Government cannot be maintained. Therefore my dear Fellow Citizens of America, you must ask leave of your wives and daughters to preserve your Repulick.” Write a short essay that evaluates these sentiments. Who are the citizens he addresses? And how should they preserve the republic? What is the role of women, and how might they fulfill it, according to Adams and other leaders and intellectuals? Due in class March 3.

Week 10

March 8: Sentimental Novels in the Republic.

Reading : The Coquette , letters 54-74. Kornfeld, 189-205, 217-28.

March 10: American Nationalism.

Reading : Kornfeld, American Culture , 149-88, 229-60.

Essay Assignment: How does Hannah Webster Foster's novel, The Coquette , answer the following question: is, or should, the new republic be a place of female as well as male freedom and liberty? Write a short essay (approximately 500 words) exploring this question.

Due in class March 10.