Sun Tracking and Sound Tracing:

Integrating Solar Design Principles in Beginning

Architectural Studios

Ihab M.K. Elzeyadi, Ph.D.

Assistant Professor

Department of Architecture

1206 University of Oregon

Eugene, OR 97403

Abstract

Site analysis in the beginning architectural studios has traditionally been focused on the cultural, formal and compositional language of the context rather than the opportunity to map and investigate sensory qualities that contribute to the design problem. In this paper, I outline a procedure of exercises that I call "Sun Tracking and Sound Tracing," which I successfully implemented during the site analysis phases of teaching beginning architectural studios. The procedure is based on the epistemological perspective that "technology is design" and environmental forces are media of architectural conception. The methodology starts with tracking the sun’s paths, tracing sounds and their sources, and observing activity patterns and people’s behavior on an urban site of a studio project. The exercise is conducted on the micro scale of the building plot, the macro scale of the city block, and the mega scale of the street.

The data collected is then synthesized and analyzed using a series of tracking plots, figure grounds, shading patterns, boundaries and thresholds diagrams, as well as behavioral maps. Following these analytical phases, students are guided to use the collected information in exploring different lighting qualities and sensory experiences they are trying to achieve in a number of design experiments which conclude with an organization of a building scheme. The scheme is then further developed to accommodate the programmatic elements of the project. To evaluate this methodology, a comparative case study was designed to observe students’ reception and integration of knowledge in their design projects for two beginning design studios. This paper concludes with the patterns of success for the presented methodology as well as the differences in student attitudes towards it. Recommendations for future research and applications are proposed.

1. Introduction

"Architecture is bound to situation. Unlike music, painting, sculpture, film and literature, a construction (non mobile) is intertwined with the experience of place. The site of a building is more than a mere ingredient in its conception. It is its physical and metaphysical foundation."

Steven Holl, Anchoring, 1989

What if solar geometry and its principles are integrated in the very early conception of buildings? This for most of us sounds like a given, if one is to consider how buildings should be oriented; shading is to be assembled; and solar insolation to be achieved. In reality, this is not the common path taken in teaching beginning architectural design studios. Beginning architectural studios, especially, focus on the formal and compositional language of architecture rather than the opportunity to integrate technical knowledge in architectural design. In this case, solar design and research knowledge follow a general misconception of being taboo, or as secondary knowledge that "doesn’t stir the architect’s soul." In this paper, I outline a methodology that I call "Sun Tracking and Sound Tracing," which I successfully implemented in teaching beginning architectural studios. The methodology is based on the epistemological condition that "technology is design" and environmental forces are the medium of architectural creation and conception. The methodology starts with tracking the sun’s paths, tracing sounds and their sources, and observing activity patterns and people’s behavior on an urban site of a studio project. The exercise is conducted on the micro scale of the building plot, the macro scale of the street block, and the mega scale of the overall street. The data collected is then synthesized and analyzed using a series of tracking plots, figure grounds, shading patterns, boundaries and thresholds diagrams, and behavioral maps. These diagrams form the basis of the student’s studio project design. Following these analytical phases, students are guided to use the collected information in exploring different lighting qualities and sensory experiences that they are trying to achieve in a number of massing experiments which conclude with an organization of a building scheme. The scheme is then further developed to accommodate the programmatic elements of the project.

To evaluate this methodology, a comparative case study was designed to observe students’ reception and integration of knowledge in their design projects for two beginning design studios. A total of 30 beginning to intermediate architectural students were enrolled in two design studios during their first and second year architecture with an average of 15 students per section. This paper outlines the patterns of behavior, design integration, and teaching pedagogy for the first and the second year architectural studio. In general, the hands-on experiential approach of tracking the sun, tracing sounds, and monitoring behavior aided students to integrate climatic and technical forces on the site in their building design. In addition, the methodology highlighted social and psychological factors that affect space hierarchies and design patterns of the building under design. This paper concludes with the patterns of success for the presented methodology as well as the differences in student attitudes towards it.

2. Site Analysis in the beginning Studio

Urban and historical site analysis is a critical part of the architectural design process. In order to develop appropriate and successful design solutions for any kind of project, students need to get involved in research explorations to understand the setting of their project both on the micro scale of the street where the building site is, and the mega scale concerned with the overall district surrounding the project site. Typical site analysis exercises in the beginning design studios focus on the systemic process of gathering various levels of information of the physical, historical, organizational, and social environments that represent the forces present on the site. Seldom does this stage of information gathering include the analysis of environmental factors, such as sun, wind, light, and sound.

For the site analysis phase of the three beginning design studios I taught at the University of Oregon during winter, spring, and fall of 2002, site documentation and analysis activities involve the following:

2.1 Documentation

Students in the studio documented and represented the building site and its surrounding block using a variety of media to document the existing conditions of the building and its context.

This included measurements of the façades and their basic features, sidewalks, and pedestrian structures, in terms of their materials, composition, proportions and how they are rendered by different lighting conditions during day and night. Using photographs, students documented activities as well as sun patterns, occupants’ behavior, as well as shade and shadow patterns on the street and the façades during different times of the day.

2.2 Building Stories/Context

In this part of the site analysis phase, students researched the history of the buildings surrounding the site. They reported mile stone transformations that occurred to their existing site, and how these changes have affected environmntal conditions (sun, wind, light, sound) of the site and its context.

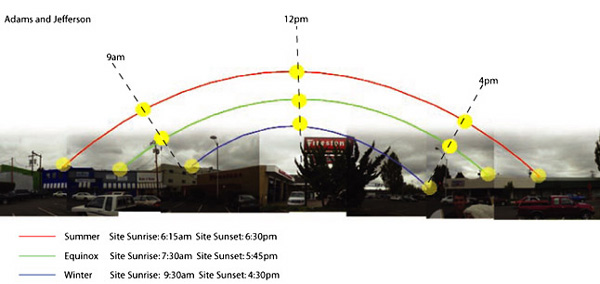

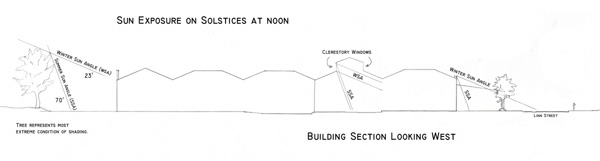

2.3 Sun Tracking

Sun tracking was conducted using the "Solar Transit" to determine the solar access to the site by modeling the seasonal path of the sun across the street block and locating horizon obstructions. In addition, students used "sun angle calculator" to cast shades and shadows of the buildings in the block of the street of their site for winter solstice (December 21st), summer solstice (June 21st), and the equinox (March & September 21st) at 9:00 AM, Noon, and 4:00 PM.

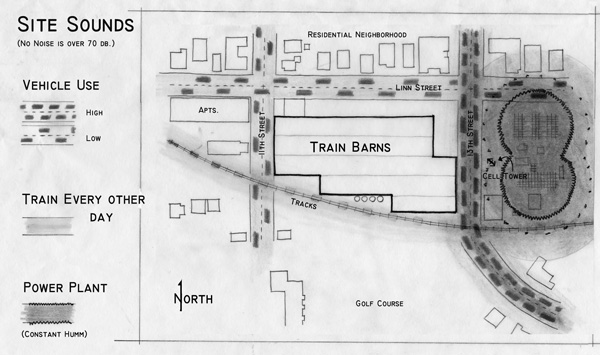

2.4 Sound Tracing

Students traced the sources of sound and noise (unwanted sounds) in the street, measured its intesity in decibel (dB) level, rated the degree of its pleasantness or annoyance, recorded a sample of the sound, and traced its source of origin. This information was then recorded on a site plan and supported with photographs and text descriptions.

2.5 District Study

Students were asked to analyze the district surrounding their project site in terms of its land use and types of buildings as well as the systems of activities and the different settings where those activities take place. This analysis covered information regarding the level and concentration of activities (large groups, small groups), types of activities (shopping, hanging-out, skateboarding, exercising, etc.), and the description of the activity (public/private, formal/informal, central/peripheral, required/voluntary, legal/illegal, etc.). This phase of the site analysis documented the setting/space where the different activities occur. This included the qualities of this settings, solar access, noise, sounds, and air velocity, as well as what attributes make it suitable for the activities occurring in it.

In addition to activities, sutdents located the nodes, paths, thresholds, and landmarks that define the sense of the district (2). They also recorded the approaches and connections between the district, where the site is located and the rest of the city, retracing the paths of arrival taken by people to reach the site and district.

3. Sun Tracking Design Explorations

The sun traking component of the site analysis was conducted using a triangulation of three approaches; (1) documenting solar penetration to the site using a solar transit at different times of the day and during summer and winter solstices and on the equinox (Figure 1), (2) casting shades and shadows of the street site plan and façades during the same studied times by using a sun angle calculator to determine the altitude and azimuth angles for different times of the day and during summer and winter solstices and the equinox, and (3) documenting how light renders facades and context using digital time lapse photography.

Figure 1: Sun tracking with a solar transit.

In addition to the documentation of light quality and solar access to the site and the street, students were engaged in the following design explorations with respect to the design project and program of the studio:

3.1 Solar Design Exploration 1 – Layers of Light

For this design exercise, students designed a sequence of spaces that connect the outside and inside of the central space of their building through a series of transitional spaces that are designed with various degrees of light and shadows. The form and geometry of these series of spaces considered the quality and quantity of light (Figure 2).

Figure 2: A daylighting model by student Anne Stende exploring different degrees of light progression.

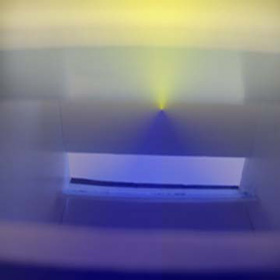

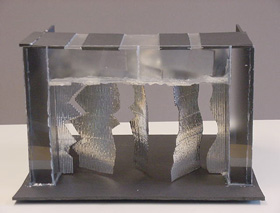

3.2 Solar Design Exploration 2 – Sensory Space

In this second exercise with light students focused their design experiment on one room inside their building with consideration for the following spatial qualities in relationship to light and its role in creating a sensory spatial experience (Figure 3):

- Scale (S, M, L, XL).

- Texture (smooth – rough)

- Colors (monochrome – multi-color)

- Thermal (cold – warm)

- Order (symmetry, hierarchy, radial, etc.)

- Volume (mass – mass-less)

- Embodiment (wrapped – wrapping)

- Containment (contained – container)

- Rhythm (repetitive – unique).

- Approach (direct – indirect)

Figure 3: Exploration into sensory qualities of daylighting by Scott Thorson.

4. Sound Tracing Design Interventions

The sound tracing component of the site analysis was conducted using two research procedures. First, students were asked to document different sounds that exist on the site, measuring their intensities in decibels, rating the annoyance or the pleasantness of the sounds, and tracing the location and frequencies of the sounds. The second procedure for tracing sounds on the site involved recording these sounds as well as human behavior in relation to these sounds using tape recorders, video cameras, and digital time lapse photography. This information was documented and analyzed for different times of the day during a typical weekday and a weekend day (Figure 5).

Figure 4: Sound tracing and analysis.

In addition to documentation of sound quantity and quality in the site and the street, students were engaged in the following design explorations with respect to the design project and program of the studio:

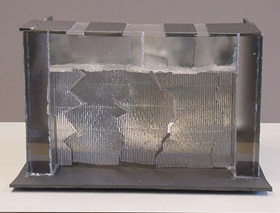

4.1 Sensory Acoustical Transitions

For this design exercise, students were asked to explore spatial thresholds and connectors using water and sound as materials to create memorable spatial transitions. The form and geometry of these transitions were intended to engage the senses. Live demonstrations of installations in models were presented to the entire studios for feedback and future implementation in their project design (Figure 5).

Figure 5: Exploration into sensory transitions using water, sound, and light as media by Rachel Anderson.

4.2 Sensory Acoustical Installation

For this design exercise, students designed a sensory installation of a component or detail in their design that engaged the senses through the use of sound, light, and water (Figure 6). The spatial installation was intended to engage one or more of the senses. This installation was either part of a larger space/room or a scaled version of a larger space. Despite its scale, the installation was designed to engage the senses in the same manner as the full-scale version.

Figure 6: Sensory acoustical installation by James Birkey.

5. Design and Research Process

The site analysis was divided into two phases. The first phase was to gather information regarding the environmental forces that have an impact on the light, wind, and sounds available on site. This phase was conducted in groups of two to three students responsible for different tasks. The second phase was to filter this information to determine its value, which was an individual task taken by each student in the studio. In addition, each student was engaged in a presentation of their findings in a thorough, descriptive, and inspirational manner to inform future design decisions. This was further translated into a series of descriptive and impression-based digital and analog models that linked the design development phase with the conceptual design phase following the site analysis.

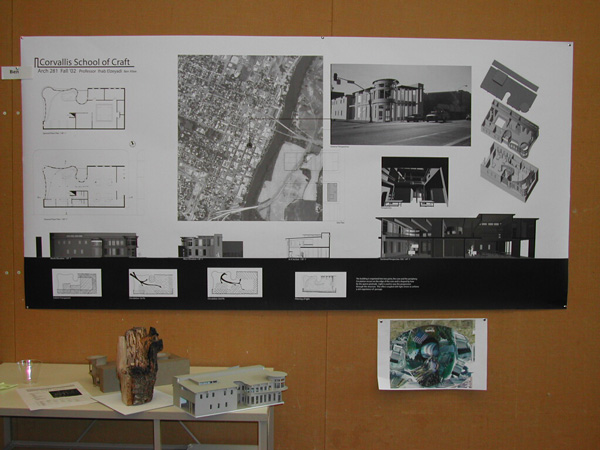

Figure 7: Corvallis Arts & Crafts Center – final design presentation by second year architecture student Ben Allee.

6. Conclusions

Through a review of the outlined research and design activities, this paper demonstrated a methodology and procedure for integrating environmental and solar design knowledge in the early phase of beginning architectural studios. While final students’ designs were influenced by the presented exploratory exercises in different ways, the general design objective was to help students realize the importance of daylight and acoustics as design primers for the creation of sensory timeless spaces (Figure 7).

Based on my experience with this methodology in three beginning architectural studios, the timing of the exploratory exercises and the building type for the studio project played an important role in the degree of integration of knowledge in the final design scheme. It is important to assign a building that is moderate in size, of commercial type, and contain an important central space or quintessential room. The building program and square footage of the different spaces should be kept flexible to allow students to explore different design options with light and sound qualities rather than be tied to spatial planning at this early design stage. It was the main objective of this paper to convey a brief summary of the different exercises and design explorations that help students integrate solar and environmental knowledge in the early design stages of design at beginning architectural studios. The hope is to spur future discussions and application of the proposed model and contribute to a better understanding of integrating technical knowledge in architectural design education.

7. Acknowledgements

I would like to acknowledge the creative and exploratory attitude of my students in Arch 181, 182 & 281, beginning architectural studios, during the winter, spring, and fall terms of 2002 respectively, at the Department of Architecture, University of Oregon. I would also like to thank my colleagues Virginia Cartwright and Christine Theodoropoulos for our discussions and their suggestions.

|