Kanadehon Chūshingura 仮名手本 忠臣蔵

in Woodblock Prints

(prints from the collection)

PRINTS RELATED TO PERFORMANCES OF CHŪSHINGURA

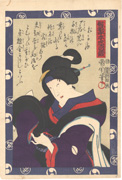

Utagawa Hiroshige II (1826-1869)

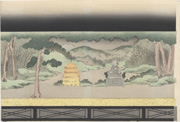

Utagawa Hiroshige II (1826-1869)

CHARACTERS FROM CHŪSHINGURA

HISTORICAL PRINTS

Play Summary

Source: http://www.naritaya.jp/english/show/detail.php?no=2009100120091025190517Originally written for the puppet theater by Takeda Izumo II, Miyoshi Shoraku and Namiki Senryu, it was first performed in 1748 at Takemoto-za, Osaka. It was first staged as Kabuki the same year at the Arashi-za, Osaka.

Kanadehon Chūshingura is based on a true incident, the Akō incident, which took place between 1701 and 1704. To avoid censorship by the ruling shogunate government, the authors set the play in the earlier Muromachi period (1336-1573) and the names of the characters were altered.

The central story concerns the daimyō Enya Hangan [the historical daimyō was Asano Takumi no Kami Naganori], who is goaded into drawing his sword and striking a senior lord, Ko no Morono [the historical protocol officer Kira Kōzuke-no-suke Yoshinaka]. Drawing one's sword in the shogun's palace was a capital offence and so Hangan is ordered to commit seppuku, or ritual suicide by disembowelment. The ceremony is carried out with great formality and, with his dying breath, he makes clear to his chief retainer, Ōboshi Yuranosuke, that he wishes vengeance upon Morono.

Forty-seven of Hangan's now masterless samurai or rōnin bide their time. Yuranosuke in particular, appears to give himself over to a life of debauchery in Kyoto's Gion pleasure quarters in order to put the enemy off their guard. In fact, they make stealthy but meticulous preparations and, in the depths of winter, storm Morono's Edo mansion and kill him. Aware, however, that this deed is itself an offence, the retainers then carry Morono's head to the grave of their lord at Sengaku-ji temple in Edo, where they all commit seppuku.

Note, in addition to The Treasury of Loyal Retainers the play is also referred to in English as The Forty-Seven Samurai, The Forty-Seven Rōnin, The Revenge of the Forty-Seven Samurai and variations of the foregoing.

Kanadehon Chūshingura in Color Woodblock Prints

The most impressive legacy of Kanadehon Chūshingura in print is the large number of color woodblock prints that were made primarily to advertise upcoming performances by showing the major actors in well-known scenes, but which also extended into a variety of peripheral genres as well. In general, only a limited number of dramatic high points were selected for illustration, so that the same scenes were depicted over and over. This part of the exhibition moves through Kanadehon Chūshingura act by act, skipping only Act II, which is considered inferior and is rarely performed, and Act VIII, which is a michiyuki travel scene in the original jôruri text, but which was replaced in kabuki after 1833 with a completely different michiyuki performed after Act III.

Many kabuki prints, particularly those of the nineteenth century that account for most of the ones on display here, were issued in multiples of two (diptychs) and three (triptychs). This was a general tendency in late Edo prints, and was done in part to overcome the size limitations of the printing blocks, which could not exceed the normal dimensions of the wild cherry tree from which they were made. The multi-sheet formats also offered the possibility, however, of enjoying each single sheet separately. Many of these works can thus be visually apprehended in two different ways, either as a multi-sheet unit showing actors interacting with one another, or as single portraits of specific actors.

The majority of kabuki prints depicting Kanadehon Chūshingura were intended for a specific performance, which can be identified by the crests of the actors playing particular roles. They served in this way as both advertisements and documents of one-time performances, and were rarely reprinted, so that the total number of any one print probably ran from one hundred to several hundred copies.

The total variety of different Chūshingura prints, however, was very large, particularly if we include the many plays that were derivative of Kanadehon Chūshingura, a category known as kakikae, or “re-writes.” In addition, some prints depicted not a particular performance, but a generic Chūshingura scene, sometimes with specific actors, sometimes not even related to the kabuki stage but rather illustrating the jōruri narrative. Of a total of some 800 Chūshingura-related prints in the Tsubouchi Memorial Theatre Museum at Waseda, 45 percent show specific performances of Kanadehon Chūshingura, 18 per cent depict kakikae performances, and 37 percent are of a generic or miscellaneous type.

The total number of different Chūshingura prints ever issued was long thought to be in the range of 1500-2000, but in the preparation of a complete catalog of such prints that is soon to be published by Akō City, it has been discovered that the actual number is closer to 5000, constituting a huge body of visual material on this single play and its many spin-offs.

In this exhibition, the artist who appears with by far the greatest frequency is Utagawa Kunisada (1786-1865), who used the name “Toyokuni III” after 1844. He accounts for one-third of the prints shown here, followed by his fellow Utagawa school contemporary Kuniyoshi (1797-1861), with half as many. All the rest are by scattered different artists.

Meiji-Era Chūshingura Prints

Source: The below excerpts are taken from Chelsea Foxwell's "The Double Identity of Chūshingura: Theater and History in Nineteenth-Century Prints," appearing in Impressions Number 26, 2004, p.23-43.

It was in the Meiji period that the goal of linking the Chūshingura drama to its historical setting came closer to onstage realization. The project of enriching kabuki with a greater degree of historical accuracy became a pillar of the state-supported kabuki reform of the 1870s through the 1890s. Kawatake Mokuami and Ichikawa Danjūrō IX strove to infuse kabuki characterization and staging with "realism"; historians coached Danjūrō on a monthly basis in an effort to increase the historical fidelity of the productions. In November 1868, less than one year after the capitulation of the Tokugawa shogun to forces proclaiming the restoration of direct imperial rule, thus inaugurating the Meiji period (1868-1912), Emperor Meiji issued a letter of commendation to the men of Akō. During a time when it was still battling opposition, the new government clearly stood to benefit from the long-standing popularity of a narrative that emphasized loyalty to ones lord, a feeling that might now be directed toward the emperor himself. When he [the emperor] entered Tokyo in the fall of 1868, the government made assiduous efforts to win the hearts and minds of the people through patronage of the most popular places of commoner pride and devotion, including Sengakuji. By the late Edo period, numerous exhibitions of rōnin ephemera accompanied the affirmation of Sengakuji as an important urban site for commemorating the Akō incident and its principal agents. After imperial envoys conveyed the letter to the retainers graves at Sengakuji, the spirits of the "loyal league" were enshrined in a new memorial hall near the temple grounds. There, the forty-seven wooden statues commissioned in the 1840s by a group of private individuals were put on display.During the slow collapse of Tokugawa power and the construction of the Meiji state, kabuki was freed from general restrictions on the representation of current events and of the Ako incident, which had occurred more than one hundred and fifty years earlier. Theater prints of the 1860s and 1870s indicate that performances now appropriated the full range of Chūshingura traditions, reformulating them for the stage. The prints document the production of witty Chūshingura pieces, including new compositions by the celebrated playwright Kawatake Mokuami ( 1816-1893). Performed at the most important theaters of the capital, these plays drew on the main tale or on stories of the individual retainers. The corresponding images bear little relation to the Edo-period landscape print. They candidly acknowledge the architecture of the stage, showing the actors against brightly patterned sliding doors or a stage curtain.

last revision:

4/27/2021

1/10/2019