Prints in Collection

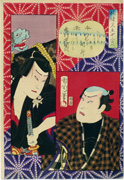

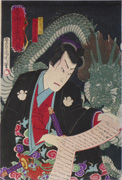

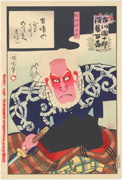

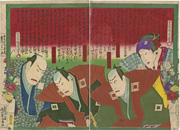

Iwai Hanshirō VIII, Ichikawa Monnosuke V, Ichikawa Danjūrō and Nakamura Nakazō III in Ura Omote Yanagi no Uchiwae, 1875

IHL Cat. #711

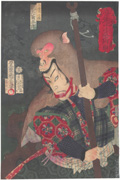

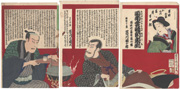

Soga Brothers New Year's Farce, 1878

IHL Cat. #616

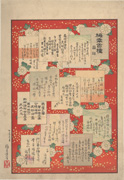

The Subscription List, 1883

IHL Cat. #403 IHL Cat. #597

IHL Cat. #597

A Comparison of Actors' Wages,

c. 1883

IHL Cat. #643

IHL Cat. #1655

IHL Cat. #1655

Ichikawa Sadanji, Ichikawa Danjūrō and Nakamura Fukusuke in the play The Subscription List, 1887

IHL Cat. #398

IHL Cat. #485

IHL Cat. #485

IHL Cat. #751

IHL Cat. #389

IHL Cat. #705

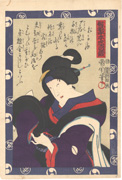

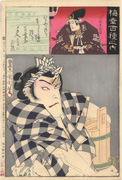

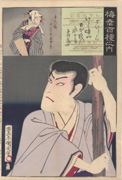

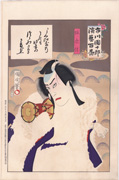

Ichimura Uzaemon

from the series

Kabuki 36 Poems, 1865

IHL Cat. #576

Haiyū mitate jūnishi, 1869

IHL Cat. #568

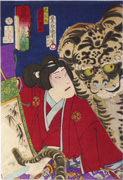

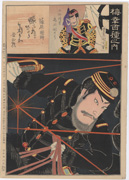

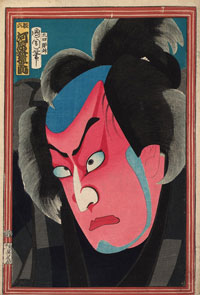

The Actor Nakamura Shikan in the role of Ishikawa Goemon

from the series Twenty-four Favorites of New Civilization, 1877

IHL Cat. #394

The Manrin Restaurant, Shinagawa-chō from the series Thirty-Six Modern Restaurant, 1878

IHL Cat. #2186

-intentionally left blank-

-intentionally left blank-

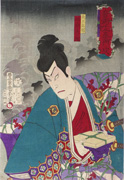

Beauty drinking tea from the series Newly Woven Brocades: Beauties of Musashi, 1883

IHL Cat. #1260

IHL Cat. #2156

One Hundred Roles of Baikō, 1893

IHL Cat. #2159

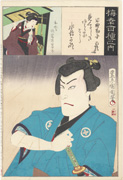

Onoe Kikugorō V as Seishin,

No. 40 from the series

One Hundred Roles of Baikō, 1893IHL Cat. #2157

Onoe Kikugorō V as Hayano Kampei, No. 50 from the series

One Hundred Roles of Baikō, 1893

IHL Cat. #2158Onoe Kikugorō V as Washi no

Chōkichi, No. 57 from the series

One Hundred Roles of Baikō, 1893/1894

IHL Cat.#2053

IHL Cat.#2052

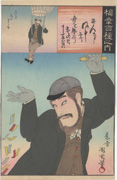

Onoe Kikugorō V as the Englishman Spencer, No. 71 from the series

One Hundred Roles of Baikō, 1894

IHL Cat. #1266

One Hundred Roles of Baikō, 1894

IHL Cat. #2167

-intentionally left blank-

-intentionally left blank-

One Hundred Roles of

Ichikawa Danjūrō, 1898IHL Cat. #683Ichikawa Danjūrō IX as Daikokuya Sōroku from the series

One Hundred Roles of

Ichikawa Danjūrō, 1898

IHL Cat. #701

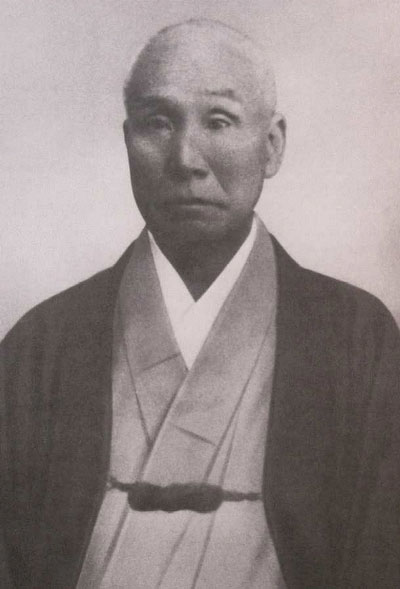

Toyohara Kunichika 1897, Photograph by Hiraki | ProfileToyohara Kunichika 豊原国周 (1835-1900)Source: University of Alberta Art Collection website http://www.museums.ualberta.ca/art/details.aspx?key=20588 Born in 1835, Toyohara Kunichika grew up in the Kyobashi district of Edo in the midst of merchants and artisans. In 1848, at age 13, he was accepted as an apprentice into the studio of Utagawa Kunisada I (Toyokuni III 1786–1865). Kunichika's work stands in contrast to that of many of his contemporaries as he persistently held onto the traditional style and subject matter of the classic Japanese woodcut, unaffected by new Western forms of art. His love of Kabuki inspired him to depict actors in their various roles and varying facial expressions. His skillful use of color and ability to translate the actor's depth of emotion onto the page makes his work some of the most dramatic ever produced. Later on in his career, Kunichika turned primarily to the triptych format as the increased size gave him the space to fully portray the drama and action of the characters represented. |

Biography

Toyohara Kunichika 豊原国周 (1835-1900)Source: Database on Yakusha-e Prints from the Ohe Naokichi Collection of Toyohara Kunichika’s Ukiyo-e Prints Kyoto University Art and Design http://kensaku.kyoto-art.ac.jp/ukiyoe/kuni_e.html and Time Present and Time Past: Images of a Forgotten Master: Toyohara Kunichika (1835-1900), by Amy Reigle Newland, Hotei Publishing, 1999

By one report, Toyohara Kunichika changed residences over 110 times while changing wives 40 times. He once boasted, “Although I can't equal Hokusai in art, I beat him in the number of times I've moved.” He spent money as in the saying, “A true Tokyoite doesn't save a penny even for one night” and although he was a heavy drinker, he possessed fine manners. Indeed, Kunichika's life is full of colorful anecdotes.

Kunichika was known as one of “The Three Greats of Meiji Ukiyo-e”, along with Yoshitoshi Tsukioka (1839-1892) and Kiyochika Kobayashi (1847-1915), and received praise as the “Meiji Sharaku”, a reference to the Edo period Ukiyo-e artist, Sharaku.

Kunichika was born Oshima Yasohachi in the Kyobashi area of Edo (now Tokyo) in 1835. His father, Oshima Kyuju, was the proprietor of a public bathhouse. He assumed the surname of Arakawa from his mother, Arakawa Sannojo, sometime during his youth. The name Arakawa Yasohachi 荒川 八十八 appeared on Kunichika's works after 1875 when artists' and publishers' names and addresses were required on prints.

At around the age of eleven Kunichika first studied under the artist (Ichiosai) Toyohara Chikanobu.1 In 1848 he became an apprentice to the artist Utagawa Kunisada (Toyokuni III, 1786-1865). His first prints as an apprentice were published in the early 1850s.2 His apprenticeship was formative, as he remained grounded in the Utagawa style he was taught in Kunisada's studio, even after he achieved artistic independence during the mid 1860s-70s.

The name Kunichika is a combination of the artist names of his two teachers, Toyohara Chikanobu and Utagawa Kunisada. Following tradition, he assumed the last character, kuni, from Kunisada's artist's name Toyokuni to which he added the character chika from Chikanobu.

Kunichika's rise to prominence can be seen in his high ratings from the saikenki (a popular guide that rated ukiyo-e artists), in which he was rated #8 in 1865, #5 in 1867 and #4 in 1885.

Kawarazaki Gonnosuke as Daroku | The smoke from the Boshin Civil War had not yet completely cleared in 1869 when Kunichika began publishing his series of large portraits of kabuki actors. Kunichika's incorporation of family crests and patterns of actors in his composition was an adopted technique from his teacher, Kunisada. Kunichika in these prints literally fills the composition with the actor's face, so it is more appropriate to refer to his pictures as ogao-e, “Large Face Pictures”. His colorful backgrounds were made from imported chemical dyes such as dark blue, red and purple. In the next three years, Kunichika made large diptych and triptych half-body series of portraits of actors. For the triptychs, he printed half body portraits of each actor in an exaggerated long format. As a print designer creating yakusha-e (actor prints), Kunichika was a regular visitor backstage at the Kabuki theater. He made sketches of actors before and during performances and at rehearsals. He was described by one of his subjects, the actor Matsusuke IV, as assuming "the 'mien' of a great artist," silent and intense. He had an intimate knowledge of every aspect of the theater, being well acquainted with plays, playwrights, actors and their performance styles. |

No other Meiji woodblock artist specialized to the same degree as Kunichika in chronicling the personalities and events of the early to mid-Meiji Kabuki theater. His prints document the roles assumed by all the leading actors of the day, but especially the three greatest performers Ichikawa Danjūrō IX (1839-1903), Onoe Kikugorō V (1844-1903) and Ichikawa Sadanji I (1842-1904), known collectively as the Dan-Kiku-Sa.

While woodblock publishers were competing with the rise of photography, issuing prints that attempted to imitate photographic images of actors, Kunichika remained anchored in the Utagawa style of elongated faces, bold facial expressions and elaborate costumes.

1 This artist should not be confused with Kunichika's contemporary, the three year younger and one-time student, Yōshū Chikanobu (1838-1912).

2 Kunichika earliest extant print Woman after the bath, c. 1853 is signed 'picture by Utagawa Kachōrō' an early artist's name (gō) that may have preceded his gō Kunichika. (Time Present and Time Past: Images of a Forgotten Master: Toyohara Kunichika (1835-1900), Amy Reigle Newland, Hotei Publishing, 1999, p. 11.)

Critical Success, Critical Rejection and Critical Acceptance

Source: Wikipedia website http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Toyohara_Kunichika (based on material in Time Present and Time Past: Images of a Forgotten Master: Toyohara Kunichika (1835-1900), by Amy Reigle Newland, Hotei Publishing, 1999.)

The press affirmed Kunichika's success into the Meiji era. In July 1874, the magazine Shinbun hentai said that: "Color woodcuts are one of the specialties of Tokyo, and Kyôsai, Yoshitoshi, Yoshiiku, Kunichika, and Ginkô are the experts in this area." In September 1874 the same journal held that: "The masters of Ukiyoe: Yoshiiku, Kunichika and Yoshitoshi are the most popular Ukiyo-e artists." In 1890, the book Tôkyô meishô doku annai (Famous Views of Tokyo), under the heading of "woodblock artist", gave as examples Kunichika, Kunisada, Yoshiiku, and Yoshitoshi. In November 1890 a reporter for the newspaper Yomiuri Shimbun wrote about the specializations of artists of the Utagawa School1: "Yoshitoshi was the specialist for warrior prints, Kunichika the woodblock artist known for portraits of actors, and Chikanobu for court ladies."

Contemporary observers noted Kunichika's skillful use of color in his actor prints, but he was also criticized for his color choices. Unlike most artists of the period, he made use of strong reds and dark purples, often as background colors, rather than the softer colors that had previously been used. These new colors were made of aniline dyes imported in the Meiji period from Germany. (For the Japanese the color red meant progress and enlightenment in the new era of Western-style progress.)In 1915 Arthur Davison Ficke, an Iowa lawyer, poet, and influential collector of Japanese prints, and author of Chats on Japanese Prints, dismissed Kunichika's and fifty-four other artists' work as "degenerate". He went on to criticize "all that meaningless complexity of design, coarseness of color and carelessness of printing that we associate with the final ruin of the art of color prints." His opinion, which differed from that of Kunichika's contemporaries, influenced American collectors for many years, with the result that Japanese prints produced in the second half of the nineteenth century, especially figure prints, fell out of favor.

In the late 1920s and early 1930s Kojima Usui an author, adventurer, banker and great collector of Japanese art, wrote many articles aimed at resurrecting Kunichika's reputation. While he was not successful in his day, his work became a basis for later research, which did not really begin until quite recently. In 1976 Laurance P. Roberts wrote in his Dictionary of Japanese Artists that Kunichika produced prints of actors and other subjects in the late Kunisada tradition, reflecting the declining taste of the Japanese and the deterioration of color printing. He went on to describe Kunichika as, "A minor artist, but represents the last of the great ukiyo-e tradition." Richard A. Waldman, owner of The Art of Japan, said of Roberts's view, "Articles such as the above and others by early western authors managed to put this artist in the dustbin of art history." A major reason for Kunichika's return to favor in the western world is the 1999 publication of Amy Reigle Newland's Time Present and Time Past: Images of a Forgotten Master: Toyohara Kunichika 1835–1900. In addition, the 2008 show at the Brooklyn Museum, Utagawa: Masters of the Japanese Print, 1770–1900, and a resulting article in The New York Times of 03/22/08 have increased public awareness of and prices for Kunichika's prints.

Collaboration with Other Artists

During the heyday of his career Kunichika collaborated on print designs with the artists Yoshitoshi Tsukioka (1839-1892), Kawanabe Kyōsai (1831-1889) and on at least one print with Yōshū Chikanobu (1838-1912).

A Woodblock Artist's Home

Source: Time Present and Time Past: Images of a Forgotten Master: Toyohara Kunichika (1835-1900), by Amy Reigle Newland, Hotei Publishing, 1999, p.7.

In October 1898 Kunichika was interviewed for a series of four articles about him, The Meiji-period child of Edo, which appeared in the Tokyo newspaper Yomiuri Shimbun. In the introduction to the series, the reporter wrote:

For a further translation of this interview go to the Toshidama Gallery website Kunichika.net at http://kunichika.net/article_7/An-Interview-with-Kunichika-1898.htm...his house is located on the (north) side of Higashi Kumagaya-Inari. Although his residence is just a partitioned tenement house, it has an elegant, latticed door, a nameplate and letterbox. Inside, the entry...leads to a room with worn tatami mats upon which a long hibachi has been placed. The space is also adorned with a Buddhist altar. A cluttered desk stands at the back of the miserable two-tatami room; it is hard to believe that the well-known artist Kunichika lives here...Looking around with a piercing gaze and stroking his long white beard, Kunichika talks about the height of prosperity of the Edokko [a person born and raised in Edo (renamed Tokyo in 1869)]

Kunichika's Death

Source: Time Present and Time Past: Images of a Forgotten Master: Toyohara Kunichika (1835-1900), by Amy Reigle Newland, Hotei Publishing, 1999, p. 16

Kunichika died at his home in Honjo (an eastern suburb of Edo) on July 1, 1900 at the age of 65, due to a combination of poor health and bouts of heavy drinking brought on by the death of his daughter Hana during childbirth in February, 1899. He was buried at the Shingon Buddhist sect temple of Honryuji in Imado, Asakusa. His grave marker is thought to have been destroyed in a 1923 earthquake, but family members erected a new one in 1974. In old Japan, it had been a common custom for people of high cultural standing to write a poem before death. On Kunichika's grave his poem reads:

Since I am tired of painting portraits of people of this world,I will paint portraits of Enma (the King of hell) and the devils.Yo no naka no, hito no nigao mo akitareba, enma ya oni no ikiutsushisemu.

Kunichika's Students

Source: Time Present and Time Past: Images of a Forgotten Master: Toyohara Kunichika (1835-1900), by Amy Reigle Newland, Hotei Publishing, 1999, p. 30

Little is known about many of Kunichika's pupils except that, following tradition, most incorporated the character of chika from 'Kunichika' into their own art names, e.g., Chikashige, Yōshū Chikanobu (1838-1912), Toyohara Chikayoshi (fl. 1870s-1880s), Chikasue, Chikaharu and Chikamaru. Kunichika's most accomplished students, Yōshū Chikanobu (1838-1912) and Morikawa Chikashige (fl. second half 19th c.) were both contemporaries with Kunichika in age. The above mentioned Chikayoshi is Kunichika's only known female student who became, it is said, one of his many partners.

Post-Kunichika Actor Portraiture

Source: Time Present and Time Past: Images of a Forgotten Master: Toyohara Kunichika (1835-1900), by Amy Reigle Newland, Hotei Publishing, 1999, p. 30

While actor portraiture continued after his death, it was associated with artists outside of Kunichika's artistic lineage, such as Utagawa Kunimasa IV (a.k.a. Kunisada III, Baidō Kunimasa, Hosai,1848-1920) and Migata Toshihide (1863-1925) and gradually was seen as old-fashioned by a new generation drawn to the modern technologies of photography and lithography.

It was not until the publisher Watanabe Shōzaburō (1885-1962) revitalized the color woodblock print tradition in the early 1900s, with his creation of shin hanga (new prints) for the export market, that the Utagawa school actor tradition, coupled with modern aesthetics, was revived, through Watanabe contracted artists such as Natori Shunsen (1886-1960), Yoshikawa Kanpō (1894-1979) and Yamamura Kōka (1885-1942).

1 The Utagawa School, founded by Utagawa Toyoharu, dominated the Japanese print market in the nineteenth century and is responsible for more than half of all surviving ukiyo-e prints, or “pictures of the floating world.” Colorful, technically innovative, and sometimes defiant of government regulations, these prints were created for a popular audience and documented the pleasures of urban life and leisure. The prints represent famous places, landscapes, warriors, and kabuki actors; they were reproduced in books, posters, and other printed materials for mass consumption, and they fed a thriving Edo publishing industry.

Source: The Brooklyn Museum website http://www.brooklynmuseum.org/exhibitions/utagawa/

Artist Signatures (sampling)

Ichiosai Kunichika hitsu with unidentified seal |  豊原国周筆 ōju (by order) Toyohara Kunichika hitsu with Toyohara Kunichika Hakubun Hoin seal |  Toyohara Kunichika hitsu with Toshidama seal |  Kunichika hitsu |  Kunichika ga with Toshidama seal |  豊原国周画 Toyohara Kunichika ga with Toshidama seal |

![Onoe Taganojō II as Kidomaru, Ichikawa Danjūrō IX as Hirai Yasumasa, Nakamura Shikan IV as Hakamadare no Yasusuke [in Yanagi Sakura Azuma no Nishiki-e]](kunichika-toyohara-1835-1900-/Fujiwara Playing the Flute ihl2176 thumb web.jpg)