Prints in Collection

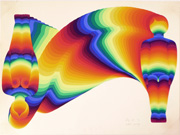

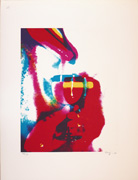

| Rainbow night 8, 1971 IHL Cat. #817 |

IHL Cat. #1472 | IHL Cat. #2035 |

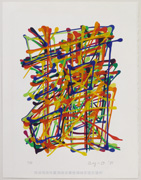

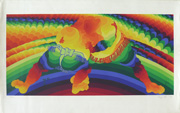

Prints from the 1974 portfolio

<Then, Mr. Ay-o got drunk by the Rainbow> <Very popular story> <Event for prints>

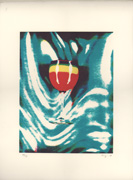

<Rainbow glass>

| Print 1 IHL Cat. #1050 |

| IHL Cat. #1249 | IHL Cat. #1254 |

Print 11 IHL Cat. #1250 | Print 15 IHL Cat. #1055 | IHL Cat. #1251 |

Print 26 IHL Cat. #1087 | Print 27 IHL Cat. #1088 | Print 28 IHL Cat. #1089 |

IHL Cat. #1322 | Print 32 IHL Cat. #1323 | IHL Cat. #1252 |

| IHL Cat. #1253 |

| Cézanne, 1976 IHL Cat. #890 | Heart Sutra, 1981 IHL Cat. #819 | Sumo Wrestling, 1984 IHL Cat. #816 |

Biographical Data

Profile

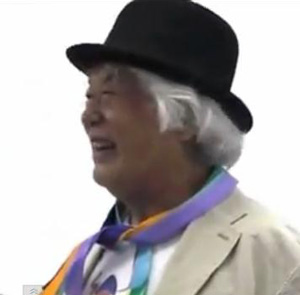

Ay-O 靉嘔 b. 1931 Ay-O at his 2012, 81st birthday party wearing his signature hat. | Known as the "Rainbow Man" the artist Ay-O is going strong at the age of 81. Installation and performance art, painting, sculpture and prints are all part of his oeuvre. Residing for many years in New York, he was an active member of the international Fluxus anti-art movement which included avant-garde musicians, poets, composers, writers and artists. Drawn to print making in the late 1950s, it was in 1964 that he began producing his signature rainbow prints, made famous at the 1966 Venice Biennale. His subsequent work has been called "a continuing celebration of the rainbow."1 |

1 Contemporary Japanese Prints: Symbols of a Society in Transition, Lawrence Smith, Harper & Row Publishers, 1985, p. 27.

Biography

Source: "The varied colors of artistic process," C.B. Liddell, The Japan Times http://www.japantimes.co.jp/text/fa20120301a1.htmland as footnoted. All quotes from Liddell article unless footnoted otherwise.

| Born in 1931 as Iijima Takao 飯島隆雄 in Ibaragi Prefecture, he took the name Ay-O after graduating from the Tokyo University of Education in 1954. Exhibiting work at the "famously permissive" Yomiuri Independent Exhibition while still in college, Ay-O was part of the watershed period of postwar Japanese art that rejected many aspects of Japanese culture. In 1955 he joined the Demokrato Artists Association (Demokurato Bijutsuki Kyōkai), created by the artist Ei-Q (1911-1960), which promoted artistic freedom and independence. In the same year he founded the short-lived group Existentialists (Jitsuzon-sha) with the printmaker and writer Ikeda Masuo (1934-1997) and the artist Manabe Hiroshi (1932-2000), among others. It was in this period that his brightly-colored oil paintings began attracting notice. |

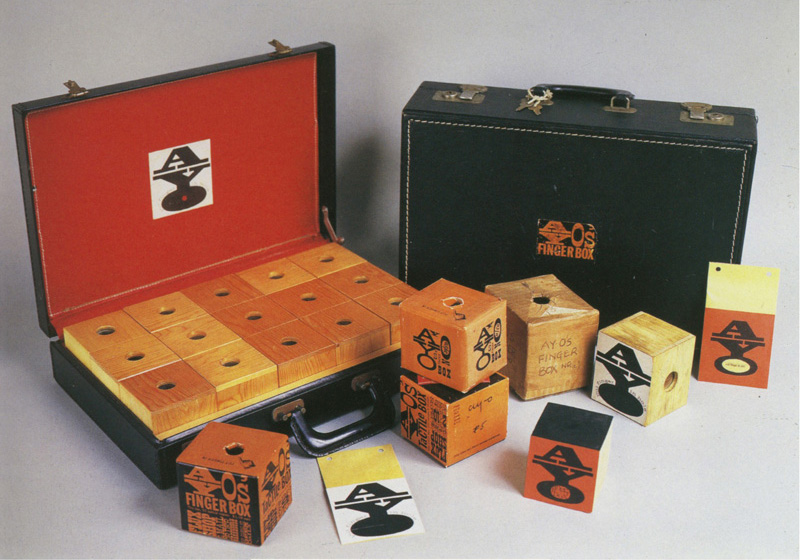

Finger Box, c. 1964-65

Fluxus Edition: mixed media in suitcase

Ay-O’s finger boxes feature a finger-sized hole with various hidden materials placed inside

(different in each, like nylon stocking, Vaseline, rubber or nails) to challenge tactile perception.

Fluxus Edition: mixed media in suitcase

Ay-O’s finger boxes feature a finger-sized hole with various hidden materials placed inside

(different in each, like nylon stocking, Vaseline, rubber or nails) to challenge tactile perception.

In a 2012 interview with art journalist C. B. Liddell, the artist recalled his first years in New York.

| I took my art to around 150 galleries twice a year for three years. I couldn't sell my art, but I became famous as a very funny Japanese Beatnik artist, so people would invite me every night to parties. I didn't need to (buy anything to) eat myself. But I was not happy. I was always fighting with the New York School people because they would always say art is (having) 'guts.' I would say that this kind of guts is what killed Pollock when his car crashed. |

Encountering Western artists who admired many aspects of Japanese culture such as Zen, Ay-O began to re-examine his own attitudes. He credits John Cage's Zen-inspired 1952 silent composition "4'33" with bringing about a new appreciation for the culture of his homeland. "I suddenly understood everything, and I hated my previous self and became a student of Zen - from America."

"Inspired by Cage's anti-composition, Ay-O started to search for ways to be an artist creating anti-art. In 1964, he stumbled upon the style that would come to define him. Instead of worrying about the choice of motifs and colors, he decided to use all the colors of the spectrum equally and use motifs that came to him through a wide variety of media."

| I covered the wall with dark canvas, then I painted a color, one color for each day. I did this because I hated painting and was against painting, but I liked to make things, so just a wall was OK. I thought I must use all the colors. If I start painting a visual work it has to have all the colors, I decided. |

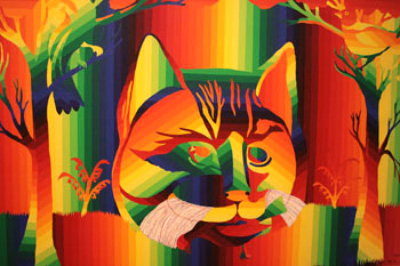

The Cat, by an Unknown Artist, about 1840 (No.6 of "NASHVILLE SKYLINE")

1971

silkscreen on paper, 36.0×51.0 cm

1971

silkscreen on paper, 36.0×51.0 cm

Ay-O returned to Japan following his teaching assignment and in 1970 he constructed his famous Tactile Rainbow Room for the Osaka World Fair, "Expo '70." In 1971 he represented Japan at the São Paulo Biennale and he remained in Japan until he left for travels in England, Europe and Nepal in 1973. The mid to late 1970s were a time of prolific print-making for Ay-O with over 130 prints created during this period.

Rainbow Environment No.7:

Tactile Rainbow Room, 1970

(Expo '70 Osaka)

Tactile Rainbow Room, 1970

(Expo '70 Osaka)

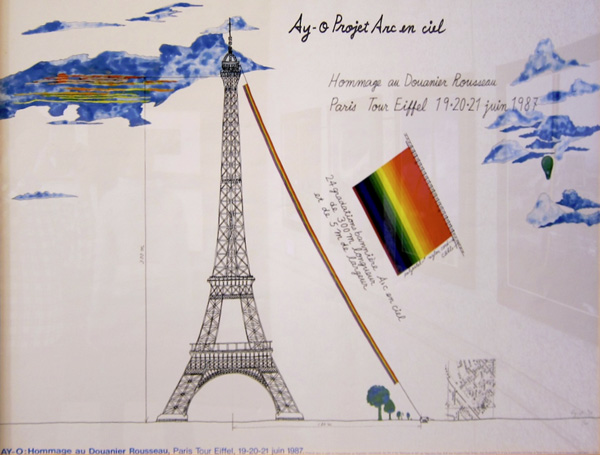

1987 brought a series of his "Rainbow Happenings," including his best known Rainbow Eiffel Tower Project in Paris in which a 300-meter rainbow banner hung for three days from the Eiffel tower, around which Ay-O placed 150 found objects painted in the colors of the rainbow.

| Ay-O's sketch for the 1987 Rainbow Eiffel Tower Project |

Ay-O observing his audience during his final performance

at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Tokyo on May 6, 2012

at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Tokyo on May 6, 2012

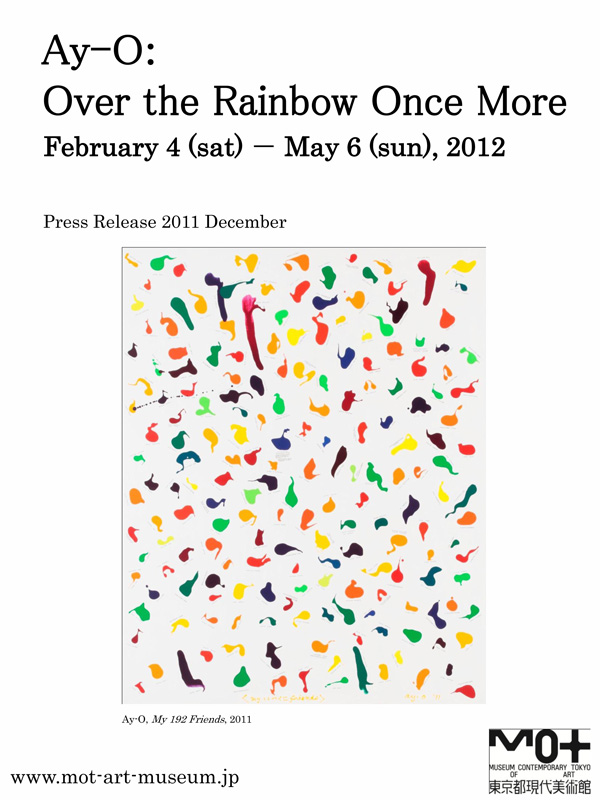

| Ay-O exhibits regularly at galleries and museums in the United States, Europe and Japan. He has had a number of solo and joint exhibitions in Japan including the 2002 Art Tower Mito (ATM) exhibition Twelve Japanese Artists from the Venice Biennale 1952-2001; the Mori Art Museum's 2005 Tokyo-Berlin / Berlin-Tokyo and its 2007 All about laughter exhibitions; the Fukui Fine Arts Museum and Miyazake Prefectural Art Museum exhibition Over the Rainbow, Ay-O Retrospective 1950-2006 (2007) and the Tsukuba Museum of Art's 2010 exhibition AY-O 1950s-2010: A Retrospective. In 2012 the Museum of Contemporary Art Tokyo mounted a large retrospective of his work titled Ay-O: Over the Rainbow Once More. His works are included in the collections of numerous museums including the National Museum of Modern Art in Tokyo and Kyoto, the British Museum, New York Museum of Modern Art; Brooklyn Museum; Cincinnati Art Museum; Fukushima Prefectural Museum of Art; Machida City Museum of Graphic Art, Tokyo; Queensland Art Gallery, Australia; Smithsonian Museums of Asian Art, Freer/Sackler; Weserburg | Museum für moderne Kunst, Bremen. |

Ay-O exhibition room at Museum of Contemporary Art Tokyo, 2012

1 Museum of Contemporary Art Tokyo http://www.mot-art-museum.jp/eng/2012/ay_o/

Fluxus

Conceived by Lithuanian ex-pat artist George Maciunas (1931-1978) in the early 1960s as a response to European domination in art and the commodification of art, Fluxus displayed "a tendency toward the spirit of the collective, toward anonymity and anti-individualism."1 Its 1963 Manifesto called on the artistic vanguard to "purge the world of 'Europanism'!"2Centered in New York City, where Maciunas landed after fleeing Lithuania at the end of WWII, it drew inspiration from the composer John Cage who is credited with inspiring the "group's interest in Asian philosophy and aesthetics - especially Taoism, Zen and the I Ching."3 Fluxus courted Japanese avant-garde artists such as Yoko Ono (b. 1933), Shigeko Kubota (b. 1937), Chieko Shiomi (b. 1938) and Ay-O "as a collective manifestation of an Eastern sensibility that corresponded with such Flux-ideas as chance, minimalism, poetics, and the investigation of the simple and habitual acts of everyday life and their inherent relation to art."4

While Maciunas put forward Fluxus's objectives as "social (not aesthetic)"5 and gave it a left-wing ideological bent, Fluxus was to become an amorphous amalgam of avant-garde artists best summed up in 1990 by Fluxus artists Eric Anderson as "a good gathering of a lot of disagreement from many good individuals" and by Yoko Ono who stated "Fluxus is what you make of it."6

Lette Eisenhauer, second from left.

With, left to right: Dick Higgins, Robert Filliou, Alison Knowles and Ay-O, 1964

Ay-O and Fluxus

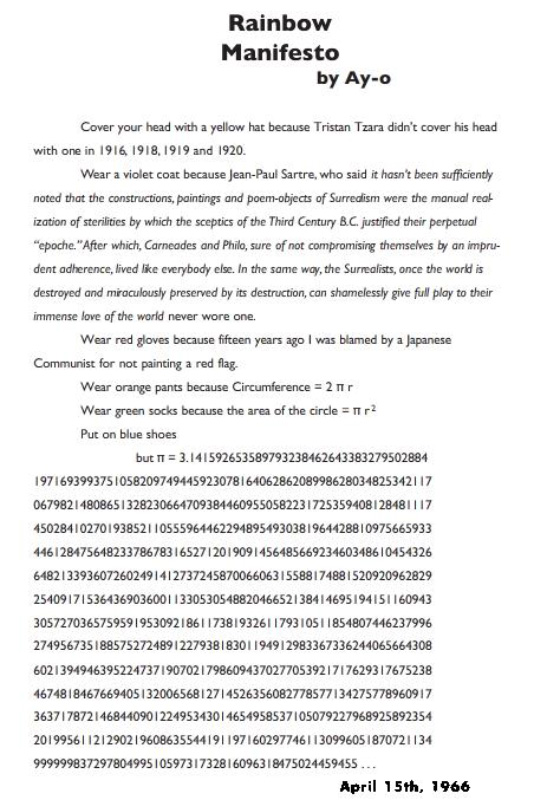

A Fluxus member from early on, Ay-O conceived of over 100 works under the Fluxus banner. Installation art, performance art, poetry and writing were all part of his contribution and all his contributions are imbued with irreverence and humor, as are his "Poem for George Maciunas" and "Rainbow Manifesto" reproduced below.

"Poem for George Maciunas"

O! George

O!! George

O!!! George

-Ay-O7

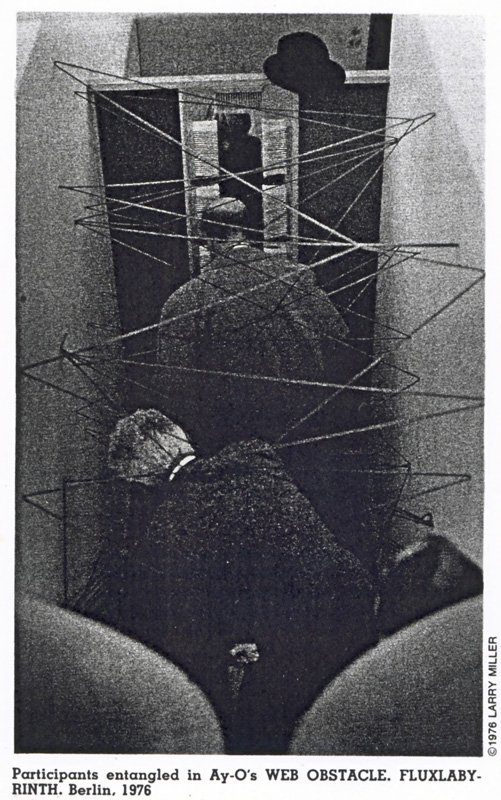

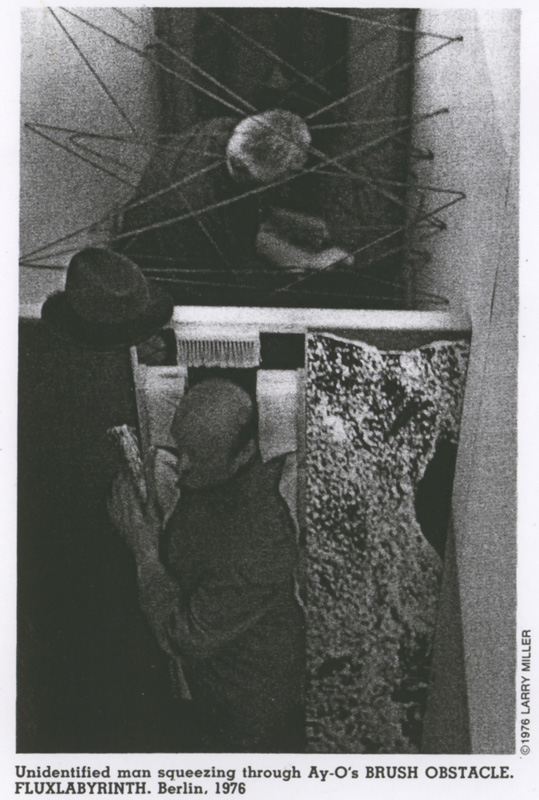

| Participants entangled in Ay-O's Web Obstacle Fluxlabyrinth, Berlin, 1976 | Beyond Ay-O's many variations of his iconic Fingerboxes, his realized and proposed Fluxus projects include Foam Room, 1963; Flux Rain Machine - A sealed clear plastic box with label. Contains moisture, 1965; Balloon Obstacle, 1966; Brush Toilet Seat, 1970-71; Mirror Floor; Rainbow Toilet Paper; Rainbow Movie; Suds in Toilet Bowl; Trapdoor Obstacle and Web Obstacle, 1976. | Unidentified man squeezing through Ay-O's Brush Obstacle, Fluxlabyrinth, Berlin, 1976 |

1 Experiments in the Everyday: Allan Kaprow and Robert Watts--Events, Objects, Documents, Benjamin H D Buchloh, et. al. , Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Art Gallery and Columbia University, New York, 1999, p. 9.

2 Japanese Art After 1945: Screen Against the Sky, Alexandra Munroe, Harry N. Abrams, NY, 1994, p. 218.

3 Ibid.

4 Ibid.

5 op. cit., Kaprow

6 Quotes: Yoko Ono, Paik, Vostell,...Fluxus-Happening-Artists, 1990 http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8UQFU-Nswro

7 Mr. Fluxus: A Collective Portrait of George Maciunas, 1931- 1978, ed. Emmett Williams and Ann Noël, Thames and Hudson, 1998, p. 125.

Ay-O's Prints

Ay-o looking through a stack of his prints, 2007 | "... to forego line and form and put the rainbow to work on the objects around him, transforming them into events."1 In the late 1950s, the critic and Esperantist Kubo Sadajirō (1909-1996) encouraged Ay-O and Ikeda Shuzo to work in printmaking, and the medium became a significant part of Ay-O's oeuvre2 and, perhaps, the best medium to display his fusing of "color, line, subject matter, and intensity...into a single element."3 Rebelling against the concept of creating works consisting of lines, Ay-O filled his motifs with the colors of the spectrum, from red to violet, giving birth to his ‘rainbow’ works and becoming famous throughout the world as the 'rainbow artist.'4 |

Before leaving Japan for New York in 1958, Ay-O had already done scores of intaglio prints and lithographs, but he did relatively little print work during his first years in New York. It was not until 1964 that he made his first "rainbow" lithograph, titled Readymade Rainbow, and it was in 1965, when he was required to submit a silkscreen print to the Japan Art Festival, that he created his first silkscreen, the print-making technique that he is most identified with.

Readymade Rainbow, 1964

Lithograph

Lithograph

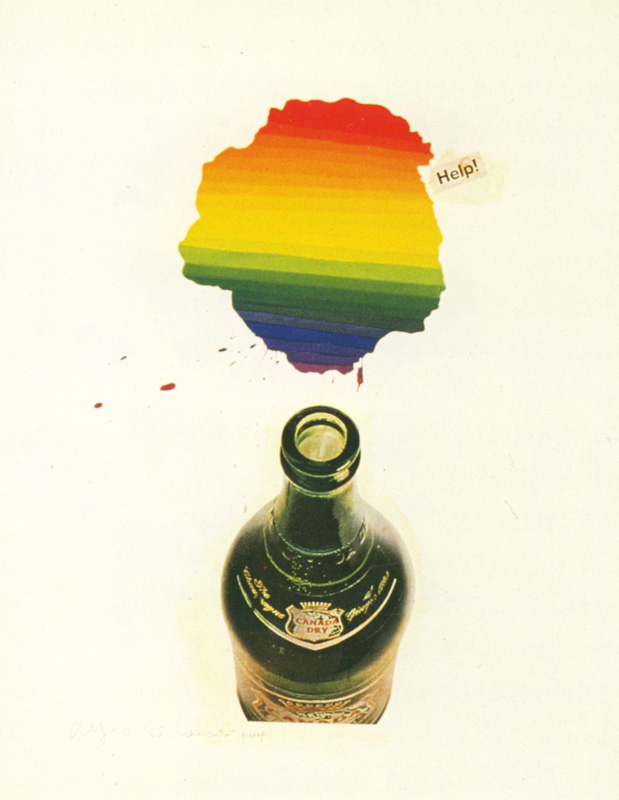

His first series of silkscreen prints, started in 1965, is titled Animated Rainbow and consists of 14 prints. Ay-O refers to this series as his "stain" prints which he created using "drops of lithographic ink, rainbow hues of oil paints, and lettering for collage taken almost exclusively from Life or Esquire."5

Animated Rainbow. Help, 1965

The first nine prints in this 14 print series were the only ones that Ay-O printed himself. All his subsequent prints he left in the hands of professional printers. As Ay-O states "none of my works, which all require at least 24 separate printings in order to achieve the rainbow-hue gradations, would have been possible without the dedicated work of such printers as Mr. Okabe and Mr. Sukeda who do the printings for me through a personal interest in my creations..."6

Writing in 1979, Ay-O explained how he works with his printers:

First I hand over just a drawing of black lines. Nowadays I generally mark the drawing with numerals from 1 to 24. I have made it arbitrary that 12 be lemon yellow, and 20 be cobalt blue. The gradations in between are left to the printer's own artistic sense to fill in along the gradations from 1 to 24 in the color spectrum starting from red and leading to purple. I do not give him a color sample. When the first print is completed I either criticize or praise as the case may be. But if he makes the next print in the same manner as the first, I will complain that there "is no progress". The poet and the artist and the printer are all the same in this respect.7

Ay-O with is printer of over 50 years Sukeda Kenryo

photo taken in 2019 at the Karuizawa New Art Museum

image source: https://knam.jp/events/2019/11335/

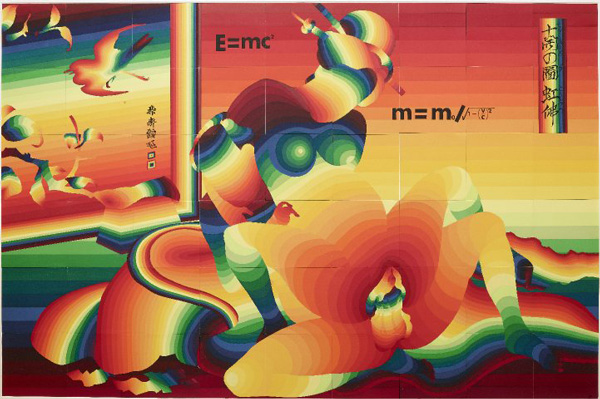

While much of Ay-O's work is not "Japanese" in subject matter, he has not ignored traditional Japanese motifs, witness this collection's print Sumo Wrestling, modeled after a work by the 18th century ukiyo-e artist Utagawa Kunisada I (1786–1865), the below shunga print Rainbow Hokusai, Position A and his 1997 portfolio An Anthology of Shunga.

Ten komanda no zu, kōbutsu 十開の圖 虹佛 (Depiction of the Ten Commandments, Rainbow Buddha) -

Rainbow Hokusai, 1970

Assembled from 54 separate square cards, each printed (screen print) with part of the design.

With purpose-made wooden storage box, printed with title.

British Museum 2011,3026.1.1-55

Rainbow Hokusai, 1970

Assembled from 54 separate square cards, each printed (screen print) with part of the design.

With purpose-made wooden storage box, printed with title.

British Museum 2011,3026.1.1-55

Ay-O An Oral History 2014

For a fascinating discussion (in English translation) with the artist go to http://www.kcua.ac.jp/arc/ar/ay-o-oral-history_en/1 Fluxus Friends blog of Alan Bowman http://fluxfriends.blogspot.com/2009/07/ay-o-rainbow-mandala-october-4-to.html

2 Art, Anti-Art, Non-Art: Experimentations in the Public Sphere in Postwar Japan 1950-1970, ed. Charles Merewether, Rika Iezumi Hiro, Getty Research Institute, 2007, p. 122

3 Who's Who in Modern Japanese Prints, Frances Blakemore, Weatherhill, 1975, p. 26.

4 Museum of Contemporary Art Tokyo, "Ay-O: Over the Rainbow Once More" http://www.mot-art-museum.jp/eng/2012/ay_o/

5 Ay-O's Rainbow Prints: Catalogue Raisonne, 1954-1979, Sadajiro Kubo, Sohbun-sha, 1979, p. 28.

6 Ibid, p. 32

7 Ibid, p. 34.

7 Ibid, p. 34.

last revision:

7/24/2021

3/16/2019