In his introduction to the catalogue of modern Japanese prints exhibited at the Art Institute of Chicago early in 1960, Oliver Statler distinguishes four generation of sosaku hanga artists. First came the pioneers, men such as Yamamoto Kanae and Tobari Kogan who pointed the way. Then came a second generation “who created a sound intellectual base for the movement, who fought through to recognition of their prints as serious art, and who, by their personal magnetism, attracted scores of younger artists.” This was the generation which began to reach artistic maturity in the early days of Showa. Though few of them had, at that time, achieved either the artistic freedom or personal style which was to characterize their later work, all were experimenting. Moreover, they were collectively striving to form some viable association which would solidify the movement and nurture its growth. These efforts, from the acceptance of such prints at the Government show of 1927 to the formation of the Nippon Hanga Kyokai in 1931, are described by Onchi in his Nippon Gendai Hanga (of which a partial translation in English appeared in Ukiyo-e Art, No. 11, 1965) and by Fujikake in his book, Japanese Wood-Block Prints (1938).

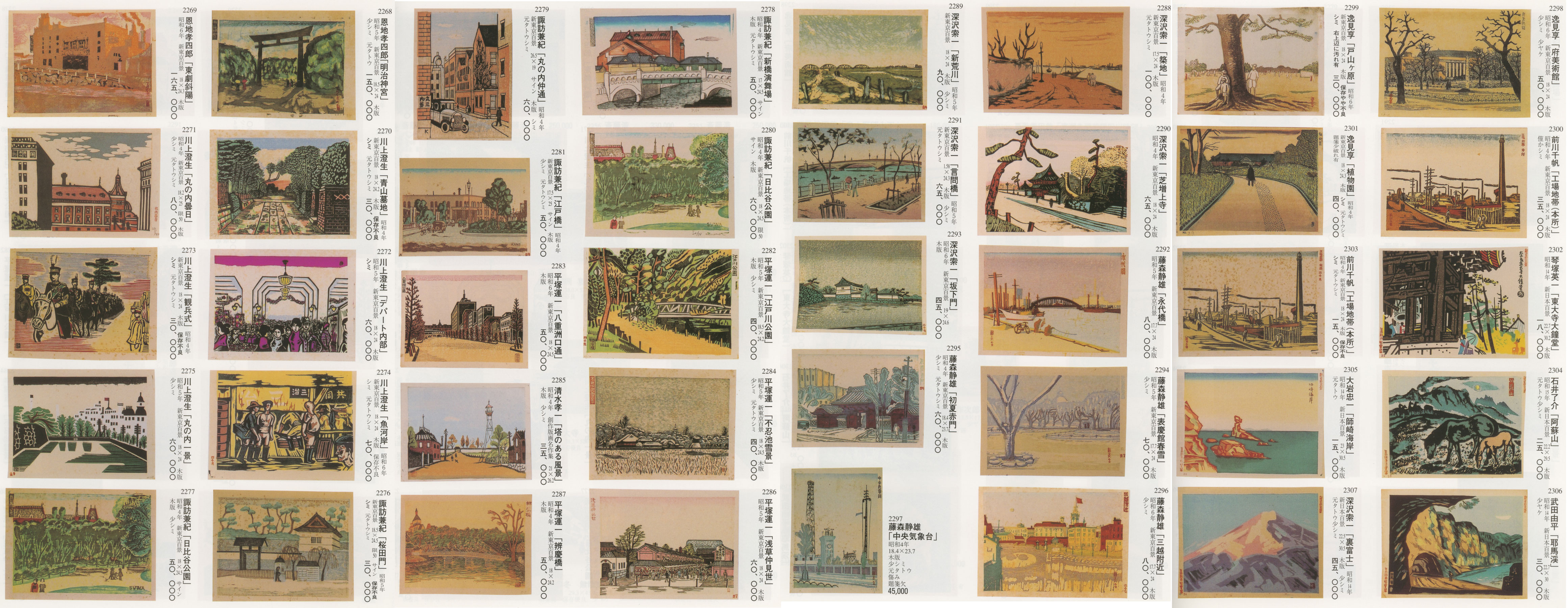

An interesting and revealing example of this tendency was a group of eight artists who, in 1928, banded together to publish, over the next four years, a series of prints entitled Shin Tokyo Hyakkei (One Hundred Views of New Tokyo). These artists were Hiratsuka Un-ichi, Onchi Koshiro, Fukazawa Sakuichi, Kawakami Sumio, Maekawa Sempan, Fujimori Shizuo, Hemmi Takashi and Suwa Kanemori. Hiratsuka recalls that this series was planned so that many aspects of Tokyo could be “remembered by people for a long time.” In this connection, one must keep in mind that much of Tokyo had been destroyed in the great earthquake and fire of 1923 so that the city and its life which the artists wished to depict were, in many respects, rather new. One cannot help wondering whether they were intending, consciously or unconsciously, to record the current scene against the possibility of new disasters. They were, in a way, repeating what Hiroshige had done 75 years before in his Meisho Edo Hyakkei series.

At any rate, the group apparently decided that each artist would make 12 or 13 prints in an edition of 50 copies. Hiratsuka was asked to make the first print which was to be, as one might expect, Nihonbashi, for centuries the central point of the city from which all distances were measured. The group obviously shared the Edokko’s long-standing fascination with bridges because many prints of the series show bridges either as the main feature or at least as a prominent part of the design. Moreover, most of the old canals still existed then and were an essential part of Tokyo life. Today, as one looks at these prints and realized how many of the canals and bridges have disappeared or been smothered by freeways, it is easy to understand what these artist wished to preserve.

Writing about the series in the Bulletin of the Hanga Club in February 1932 (p. 2), Maekawa Sempan [Senpan] reported the following:

The Shin Tokyo Hyakkei series was issued on a subscription basis. There were 50 sets, each of them numbered. Each print appeared in a mat accompanied by a mimeographed slip of paper giving the name of the artist, the title, and, in most instances, the date. The set described here is No. 31.

The individual prints vary in subject, in technique, and in the kind of paper and colors used. Some prints look back, as for example, Hiratuska’s print of Shinobazu Pond in Snow (No. 56). Fukazawa’s view of Shiba Zozoji Temple (No. 76) might well have been taken from one of Hiroshige’s prints of the same place. Others look ahead, as in Onchi’s view of the interior of a cinema (No. 29) or Fukazawa’s of a Shell gasoline station (No. 84) which reminds one strongly of some of the Pop art of today. Many prints are pure landscape; others tend more to the ukiyo-e tradition of showing the people at their amusements. Strangely enough, some of the latter are (to my taste, at least) among the least successful artistically of the series. For example, Fukazawa’s depiction of a baseball game (No. 86) and Sempan’s print of miniature golf (No. 10) seem to me to be less successful than many of the others, though they have an appeal as records of the pastimes of the early 1930’s.

There are many tricks of technique, such as the use of gaufrage to indicate rain or the wires of utility poles. There was clearly a great deal of experimentation with colors and with paper.

Some of the designs in the series have been noted before. Thus, three of them appear to have been at the show of the Art Institute of Chicago early in 1960: Fujimori’s Tsukishima (No. 32 in the AIC catalogue), Fukazawa’s Shinjuku (No. 80) and Suwa’s Fukagawa (No. 82). In addition, eight of the designs were reissued in 1945 as part of a set of fifteen entitled Tokyo Kaiko Zue, published for the Nippon Hanga Kyokai by Fugaku, with assistance in printing by Takamizawa.

In the following descriptive listing, the format of each print is indicated by H for horizontal and V for vertical. The dimensions, given in millimeters, are the average for each print size, in many cases, the edges of the print are uneven. The thickness of the paper, also in millimeters, is given after the dimensions. Again it is an average value but serves to show the relative thickness of the different papers used. The symbols UR, UL, LR and LL stand, respectively, for upper right, upper left, lower right and lower left. As a rule, the date, when given, is that supplied originally with the print. The sequence of the listings is generally chronological, e.g., Sempan, the oldest artist, appears first and Suwa, the youngest, appears last. As far as possible, the prints under each artist are listed in chronological sequence. The numbers shown at the left are merely identification numbers assigned by the present cataloguer. The prints themselves bear no numbers as to sequence in the series. References to the sources of biographical data are to the Reference Bibliography shown on page 14.

It is a pleasure to acknowledge the help received from Mr. C. H. Mitchell and Mr. Osamu Ueda. I am also indebted to Mr. Un-ichi Hiratsuka and to his daughter, Mrs. L. L. Moore. And thanks are also due to Miss Emily Biederman of the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston.

DESCRIPTIVE LISTING

MAEKAWA SEMPAN (1888-1960)

Born in Kyoto. Largely self-taught as an artist. Attained early fame as a cartoonist, and worked successfully in Tokyo for many years as a cartoonist and illustrator. During the latter part of his career, he devoted most of his time to print-making. Sempan was the oldest of the artists represented in Shin Tokyo Hyakkei; he was in his early 40’s at the time the series was published. Ref: Onchi (p. 15), Statler (pp.45-9), Fujikake (pp. 146-8), Oka (p. 10).

1. HYAKKEN-TEN, SHIBUYA (V; 242X170; 0.175). A view of the main street of Shibuya: shops on right; many dark grey figures. Signature “Maekawa Sempan” stamped in red characters, LL corner. January 19, 1929.

2. HONJO FACTORY DISTRICT (H; 242X181; 0.30). A view of the factory district on the east side of the Sumida. Roadway left with buildings on the right. Same red signature as No. 1, LL corner. May 25, 1929.

3. YATSUYAMA, SHINAGAWA

4. TORI-NO-ICHI FAIR

5. VEGETABLE MARKET, KANDA

6. LUMBERYARD, FUKAGAWA

7. SUIJO PARK

8. MEIJI-ZA

9. NIGHT SCENE AT SHINJUKU

10. MINIATURE GOLF

11. SUBWAY

12. GOTANDA STATION

FUJIMORI SHIZUO (1891-1943)

A native of Kyushu, and a close friend of Onchi’s, who shared many of Onchi’s interests and enthusiasms. Fujimori’s work ran parallel to Onchi’s up to a certain point, but never developed into abstraction. One of the senior artists of the group, Fujimori was in his late 30s at the time the Shin Tokyo Hyakkei series was published. Ref: Onchi (p. 23), Statler (pp. 155-6), Oka (p. 6)

13. ATAGOYAMA RADIO STATION

14. AKAMON, TEIKOKU UNIVERSITY

15. CENTRAL METEROLOGICAL OBSERVATORY

16. DISTANT VIEW OF NICOLAI CATHEDRAL

17. TSUKISHIMA

18. KYOKEI-KAN IN SPRING SNOW

19. KABUKIZA AT NIGHT

20. TEIDAI HALL

21. EITAIBASHI

22. YASUKUNI SHRINE

23. EARTHQUAKE MEMORIAL HALL

24. MITSUKOSHI DEPARTMENT STORE

25. UENO STATION

ONCHI KOSHIRO (1891-1955)

Undoubtedly the most forceful personality of the group, and the one with the widest intellectual interests and the deepest intellectual convictions. Although by this time Onchi was firmly committed to the creed of non-objective art, he reverted to representation in all thirteen of the prints in the Shin Tokyo Hyakkei series (such reversions occurred not infrequently in his later work as well). Onchi was in his late 30s at the time the Shin Tokyo Hyakkei series was published. Ref: Onchi (p. 21), Statler (pp. 21-34), Fujikake (pp. 139-42), Oka (pp. 6-7).

26. NIJUBASHI (H; 242X186; 0.15). A view of the famous bridge leading to the Imperial Palace. Signature “Koshiro Onchi” in hiragana with a small seal reading jizuri (“self-printed”) stamped underneath in red. March 13, 1929.

27. UENO ZOO-EARLY AUTUMN (H; 241X182; 0.27). A view of the famous zoo. At the right a family looks at a cage which appears to contain a blue seal; grey rocks behind. A tan building at the left. Signature and seal, as above, stamped in red, LL corner. September 13, 1929.

28. STREET SCENE IN FRONT OF BRITISH EMBASSY

29. HOGAKU-ZA

30. DANCE HALL

31. COFFEE SHOP

32. KYUJO HIROBA

33. HIBIYA OPEN AIR CONCERT

34. INOGASHIRA PARK

35. TOKYO GEKIYO

36. TAKEBASHI IN SNOW

37. MEIJI SHRINE

38. TOKYO STATION (V. 185X246; 0.25). A view of the entrance to the station. A canopy on columns over the entrance; above the canopy, a clock. Various figures entering or leaving. No signature or seal. Date unknown.

HEMMI TAKASHI (1895-1944)

A native of Wakayama, and a poet as well as an artist. Although Hemmi was one of the minor artists of the group he was a skillful worker and his prints are neatly and cleanly done. He was in his middle 30s at the time the series was published. Ref: Onchi (p. 23), Fujikake (p. 151), Oka (p. 9)

39. BOTANICAL GARDENS, UENO

40. KAGURAZAKA

41. MEIJI KAIGA-KAN

42. HIJIRI-BASHI

43. REINANZAKA

44. RAINY DAY AT YOTSUYA-MITSUKE

45. IMPERIAL HOTEL

46. TOKYO METROPOLITAN ART MUSEUM, UENO

47. VIEW OF PARK, HONGO MOTOMACHI

48. TOYAME-GA-HARA

49. AVENUE AT MEIJI SHRINE

50. KINSHI PARK

51. USHIGOME-MITSUKE

HIRATSUKA UN-ICHI (B. 1895)

Born in Matsue, a town made famous by Lafcadio Hearn’s sojourn there a few years before Hiratsuka was born. Studied under Ishii Hakutei, and learned engraving from the famous Igami Bonkotsu. Hiratsuka was probably the finest technician of the group; his prints stand out from the others for their technical beauty and perfection. Basically he was perhaps the most conservative artist of the group. He was in his middle 30s at the time the series was published. Ref: Onchi (p. 16), Statler (pp. 35-44), Fujikake (pp. 142-6), Oka (p. 10).

52. NIHONBASHI (H; 240x180; 0.12) – A fairly representational rendering of this famous bridge, which was for hundreds of years the hub of the city – and even Japan. Red tower and wharf, right; boats, left; many reflections on the water. The bridge is now smothered by a freeway. The print has a black border, the only Hiratsuka print in this series to have one. Sealed with character “Un” reserved on brown, upper left corner, April 25, 1929.

53. UENO PARK

54. AKASAKA GOSHO

55. BENKEI BASHI

56. SHINOBAZU POND IN SNOW (H; 242x181; 0.20) – This pond is at the southern end of Ueno Park. The print shows the Benzaiten shrine on the island in the pond, and the top of the famous five-storied pagoda in Ueno Park appears above the trees on the hill in the background. Small seal with characters “Un-ichi” in reserve on brow, lower right corner. March 5, 1930.

57. ASAKUSA NAKAMISE

58. KUROMON

59. SUKIYABASHI

60. SHIMBASHI

61. EDOGAWA PARK

62. YOYOGI-GA-HARA

63. YAESUGUCHI-DORI

KAWAKAMI SUMI (B. 1895)

Born in Yokohama. Always an experimentalist, Kawakami seems, during the period of the Shin Tokyo Hyakkei, to have been infatuated with the gaudy colors and bold stylization of Matisse, and the designs of Ginza (no. 65), At a Department Store (No. 67) and Theatre at Asakusa (No. 69) were apparently done under a strong Matisse influence. This was a passing phase, however, and there are hardly any traces of it in Kawakami’s later work. He was in his middle 30s when the Shin Tokyo Hyakkei, series was published. He is now living in Utsunomiya. Ref: Onchi (p. 17), Statler (pp. 90-3), Fujikake (pp. 152-3), Oka (p. 11).

64. AOYAMA CEMETARY

65. GINZA (H; 240X180; 0.30). A rather violently colored design of figures strolling on the Ginza, with part of an auto on the left and buildings on the right. The characters “Sumio han” appear on a sign, UR corner. August 7, 1929.

66. EMPEROR’S PARADE

67. AT A DEPARTMENT STORE

68. WASEDA UNIVERSITY

69. THEATRE AT ASAKUSA

70. VIEW OF MARUNOUCHI

71. CHRYSANTHEMUM SHOW, HIBIYA PARK

72. HAMARIKYU PARK

73. FISH MARKET

74. CLOUDY DAY AT MARUNOUCHI

75. AZABU SAN-RENTAI

FUKAZAWA SAKUICHI (1896-1946)

Although Onchi gives the date of his death as 1946, Hiratsuka believes it was January 1947. According to Hiratsuka, in his early years Fukazawa tried to express himself in Western style using mostly oil-based inks. Later he changed to Oriental style and used water-based colors. For several years before his death he designed some excellent book covers. He became a member of Nippon Sosaku Hanga Kyokai in 1928. He was in his early 30s at the time the Shin Hyakkei tokyo, series was published. Ref: Onchi (p. 24).

76. SHIBA ZOJOJI TEMPLE

77. YANAGIBASHI

78. TSUKIJI

79. HAMACHO PARK

80. KIYOSU-BASHI

81. KITOTOGI-BASHI

82. SHIN ARAKAWA

83. SHINJUKU

84. SHOWA-DORI

85. SAKASHITA-MON

86. MEIJI BASEBALL STADIUM

87. KYOBASHI

88. SENJU-OHASHI

SUWA KANENORI (1897-1932)

Hiratsuka, who was a friend of Suwa’s, has written the following about him: “He died in April, 1932. Suwa’s prints have a feeling of poetry, perhaps because he was a great poet all his life. In his early days he used to illustrate a magazine called Roman Letter Zappo, which was published in Kobe. Later this magazine became famous because of Suwa’s beautiful illustrations. He became a member of the Nippon Sosaku Hanga Kyokai in 1928. He worked as a designer for Shiseido, the cosmetics company, until his death. Since he died at such an early age, there are very few prints by him available today.” Ref. Onchi (p. 12).

89. SHIMBASHI EMBUJO

90. HIBIYA PARK

91. MUKOJIMA

92. MARUNOUCHI NAKA-DORI

93. SAKURADA-MON

94. ASAKUSA

95. EDOBASHI

96. FUKAGAWA FACTORY

97. CITY HALL, HIBIYA

98. SHIBAURA

99. NATIONAL DIET BUILDING

100. MARUNOUCHI: TOKYO STATION

REFERENCE BIBLIOGRAPHY

For images of the entire series see MIT's Visualizing Cultures website http://ocw.mit.edu/ans7870/21f/21f.027/tokyo_modern_03/kk_gal_03_thumb.html

The Modern Japanese Print, by Koshiro Onchi, Ukiyo-e Art, No. 11, 1965. (This is a translation of the central portions of Onchi’s book, Nippon Gendai Hanga, Tokyo, 1953.)

Modern Japanese Prints: An Art Reborn, by Oliver Statler. Rutland, Vt., and Tokyo, Japan, 1956.

Japanese Wood-Block Prints, by Shizuya Fujikake, Tokyo, 1938 (rev. ed. 1959)

Notes About the Taisho Print Artists, by Isaburo Oka, Ukiyo-e Art, No. 4, 1963.

An interesting and revealing example of this tendency was a group of eight artists who, in 1928, banded together to publish, over the next four years, a series of prints entitled Shin Tokyo Hyakkei (One Hundred Views of New Tokyo). These artists were Hiratsuka Un-ichi, Onchi Koshiro, Fukazawa Sakuichi, Kawakami Sumio, Maekawa Sempan, Fujimori Shizuo, Hemmi Takashi and Suwa Kanemori. Hiratsuka recalls that this series was planned so that many aspects of Tokyo could be “remembered by people for a long time.” In this connection, one must keep in mind that much of Tokyo had been destroyed in the great earthquake and fire of 1923 so that the city and its life which the artists wished to depict were, in many respects, rather new. One cannot help wondering whether they were intending, consciously or unconsciously, to record the current scene against the possibility of new disasters. They were, in a way, repeating what Hiroshige had done 75 years before in his Meisho Edo Hyakkei series.

At any rate, the group apparently decided that each artist would make 12 or 13 prints in an edition of 50 copies. Hiratsuka was asked to make the first print which was to be, as one might expect, Nihonbashi, for centuries the central point of the city from which all distances were measured. The group obviously shared the Edokko’s long-standing fascination with bridges because many prints of the series show bridges either as the main feature or at least as a prominent part of the design. Moreover, most of the old canals still existed then and were an essential part of Tokyo life. Today, as one looks at these prints and realized how many of the canals and bridges have disappeared or been smothered by freeways, it is easy to understand what these artist wished to preserve.

Writing about the series in the Bulletin of the Hanga Club in February 1932 (p. 2), Maekawa Sempan [Senpan] reported the following:

| Looking back over the Shin Tokyo Hyakkei series, it now seems to have been a very ambitious, long-term undertaking. It was in the autumn of Showa 3 (1928) when the first print by each of the eight artists represented in the series was displayed at the first exhibition of Takujo-sha. We are now in the fifth year since that time, and a five-year job is a very big one in this busy age of ours. Although the Shin Tokyo Hyakkei series was organized by Mr. Nakajima Hanga (Jutaro), it was really a cooperative venture and not an individual undertaking. Now that we are reaching the end of the series, I must express the thanks of all the eight artists who participated, not only to Mr. Nakajima Hanga but to all the others who supported the plan and assisted in the distribution, from the first term through to the final fourth term. Incidentally I must remark that Tokyo today is developing and changing very rapidly. Yesterday’s Tokyo has already changed, and there are many prints in the early part of the series showing places that have changed. So they are really “Old” Tokyo and not “New” Tokyo. Indeed, we could start on another series of Shin Tokyo Hyakkei! I can sympathize with the spirit of the older artists who turned out series of Edo Hyakkei subsequent to the Hiroshige series. Those prints have a very nice taste in accordance with the spirit of the times. It might be a good idea to start another series of Tokyo Hyakkei by other artists; this might make clearer the real width and depth of the great city. |

The individual prints vary in subject, in technique, and in the kind of paper and colors used. Some prints look back, as for example, Hiratuska’s print of Shinobazu Pond in Snow (No. 56). Fukazawa’s view of Shiba Zozoji Temple (No. 76) might well have been taken from one of Hiroshige’s prints of the same place. Others look ahead, as in Onchi’s view of the interior of a cinema (No. 29) or Fukazawa’s of a Shell gasoline station (No. 84) which reminds one strongly of some of the Pop art of today. Many prints are pure landscape; others tend more to the ukiyo-e tradition of showing the people at their amusements. Strangely enough, some of the latter are (to my taste, at least) among the least successful artistically of the series. For example, Fukazawa’s depiction of a baseball game (No. 86) and Sempan’s print of miniature golf (No. 10) seem to me to be less successful than many of the others, though they have an appeal as records of the pastimes of the early 1930’s.

There are many tricks of technique, such as the use of gaufrage to indicate rain or the wires of utility poles. There was clearly a great deal of experimentation with colors and with paper.

Some of the designs in the series have been noted before. Thus, three of them appear to have been at the show of the Art Institute of Chicago early in 1960: Fujimori’s Tsukishima (No. 32 in the AIC catalogue), Fukazawa’s Shinjuku (No. 80) and Suwa’s Fukagawa (No. 82). In addition, eight of the designs were reissued in 1945 as part of a set of fifteen entitled Tokyo Kaiko Zue, published for the Nippon Hanga Kyokai by Fugaku, with assistance in printing by Takamizawa.

In the following descriptive listing, the format of each print is indicated by H for horizontal and V for vertical. The dimensions, given in millimeters, are the average for each print size, in many cases, the edges of the print are uneven. The thickness of the paper, also in millimeters, is given after the dimensions. Again it is an average value but serves to show the relative thickness of the different papers used. The symbols UR, UL, LR and LL stand, respectively, for upper right, upper left, lower right and lower left. As a rule, the date, when given, is that supplied originally with the print. The sequence of the listings is generally chronological, e.g., Sempan, the oldest artist, appears first and Suwa, the youngest, appears last. As far as possible, the prints under each artist are listed in chronological sequence. The numbers shown at the left are merely identification numbers assigned by the present cataloguer. The prints themselves bear no numbers as to sequence in the series. References to the sources of biographical data are to the Reference Bibliography shown on page 14.

It is a pleasure to acknowledge the help received from Mr. C. H. Mitchell and Mr. Osamu Ueda. I am also indebted to Mr. Un-ichi Hiratsuka and to his daughter, Mrs. L. L. Moore. And thanks are also due to Miss Emily Biederman of the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston.

DESCRIPTIVE LISTING

MAEKAWA SEMPAN (1888-1960)

Born in Kyoto. Largely self-taught as an artist. Attained early fame as a cartoonist, and worked successfully in Tokyo for many years as a cartoonist and illustrator. During the latter part of his career, he devoted most of his time to print-making. Sempan was the oldest of the artists represented in Shin Tokyo Hyakkei; he was in his early 40’s at the time the series was published. Ref: Onchi (p. 15), Statler (pp.45-9), Fujikake (pp. 146-8), Oka (p. 10).

1. HYAKKEN-TEN, SHIBUYA (V; 242X170; 0.175). A view of the main street of Shibuya: shops on right; many dark grey figures. Signature “Maekawa Sempan” stamped in red characters, LL corner. January 19, 1929.

2. HONJO FACTORY DISTRICT (H; 242X181; 0.30). A view of the factory district on the east side of the Sumida. Roadway left with buildings on the right. Same red signature as No. 1, LL corner. May 25, 1929.

3. YATSUYAMA, SHINAGAWA

4. TORI-NO-ICHI FAIR

5. VEGETABLE MARKET, KANDA

6. LUMBERYARD, FUKAGAWA

7. SUIJO PARK

8. MEIJI-ZA

9. NIGHT SCENE AT SHINJUKU

10. MINIATURE GOLF

11. SUBWAY

12. GOTANDA STATION

FUJIMORI SHIZUO (1891-1943)

A native of Kyushu, and a close friend of Onchi’s, who shared many of Onchi’s interests and enthusiasms. Fujimori’s work ran parallel to Onchi’s up to a certain point, but never developed into abstraction. One of the senior artists of the group, Fujimori was in his late 30s at the time the Shin Tokyo Hyakkei series was published. Ref: Onchi (p. 23), Statler (pp. 155-6), Oka (p. 6)

13. ATAGOYAMA RADIO STATION

14. AKAMON, TEIKOKU UNIVERSITY

15. CENTRAL METEROLOGICAL OBSERVATORY

16. DISTANT VIEW OF NICOLAI CATHEDRAL

17. TSUKISHIMA

18. KYOKEI-KAN IN SPRING SNOW

19. KABUKIZA AT NIGHT

20. TEIDAI HALL

21. EITAIBASHI

22. YASUKUNI SHRINE

23. EARTHQUAKE MEMORIAL HALL

24. MITSUKOSHI DEPARTMENT STORE

25. UENO STATION

ONCHI KOSHIRO (1891-1955)

Undoubtedly the most forceful personality of the group, and the one with the widest intellectual interests and the deepest intellectual convictions. Although by this time Onchi was firmly committed to the creed of non-objective art, he reverted to representation in all thirteen of the prints in the Shin Tokyo Hyakkei series (such reversions occurred not infrequently in his later work as well). Onchi was in his late 30s at the time the Shin Tokyo Hyakkei series was published. Ref: Onchi (p. 21), Statler (pp. 21-34), Fujikake (pp. 139-42), Oka (pp. 6-7).

26. NIJUBASHI (H; 242X186; 0.15). A view of the famous bridge leading to the Imperial Palace. Signature “Koshiro Onchi” in hiragana with a small seal reading jizuri (“self-printed”) stamped underneath in red. March 13, 1929.

27. UENO ZOO-EARLY AUTUMN (H; 241X182; 0.27). A view of the famous zoo. At the right a family looks at a cage which appears to contain a blue seal; grey rocks behind. A tan building at the left. Signature and seal, as above, stamped in red, LL corner. September 13, 1929.

28. STREET SCENE IN FRONT OF BRITISH EMBASSY

29. HOGAKU-ZA

30. DANCE HALL

31. COFFEE SHOP

32. KYUJO HIROBA

33. HIBIYA OPEN AIR CONCERT

34. INOGASHIRA PARK

35. TOKYO GEKIYO

36. TAKEBASHI IN SNOW

37. MEIJI SHRINE

38. TOKYO STATION (V. 185X246; 0.25). A view of the entrance to the station. A canopy on columns over the entrance; above the canopy, a clock. Various figures entering or leaving. No signature or seal. Date unknown.

HEMMI TAKASHI (1895-1944)

A native of Wakayama, and a poet as well as an artist. Although Hemmi was one of the minor artists of the group he was a skillful worker and his prints are neatly and cleanly done. He was in his middle 30s at the time the series was published. Ref: Onchi (p. 23), Fujikake (p. 151), Oka (p. 9)

39. BOTANICAL GARDENS, UENO

40. KAGURAZAKA

41. MEIJI KAIGA-KAN

42. HIJIRI-BASHI

43. REINANZAKA

44. RAINY DAY AT YOTSUYA-MITSUKE

45. IMPERIAL HOTEL

46. TOKYO METROPOLITAN ART MUSEUM, UENO

47. VIEW OF PARK, HONGO MOTOMACHI

48. TOYAME-GA-HARA

49. AVENUE AT MEIJI SHRINE

50. KINSHI PARK

51. USHIGOME-MITSUKE

HIRATSUKA UN-ICHI (B. 1895)

Born in Matsue, a town made famous by Lafcadio Hearn’s sojourn there a few years before Hiratsuka was born. Studied under Ishii Hakutei, and learned engraving from the famous Igami Bonkotsu. Hiratsuka was probably the finest technician of the group; his prints stand out from the others for their technical beauty and perfection. Basically he was perhaps the most conservative artist of the group. He was in his middle 30s at the time the series was published. Ref: Onchi (p. 16), Statler (pp. 35-44), Fujikake (pp. 142-6), Oka (p. 10).

52. NIHONBASHI (H; 240x180; 0.12) – A fairly representational rendering of this famous bridge, which was for hundreds of years the hub of the city – and even Japan. Red tower and wharf, right; boats, left; many reflections on the water. The bridge is now smothered by a freeway. The print has a black border, the only Hiratsuka print in this series to have one. Sealed with character “Un” reserved on brown, upper left corner, April 25, 1929.

53. UENO PARK

54. AKASAKA GOSHO

55. BENKEI BASHI

56. SHINOBAZU POND IN SNOW (H; 242x181; 0.20) – This pond is at the southern end of Ueno Park. The print shows the Benzaiten shrine on the island in the pond, and the top of the famous five-storied pagoda in Ueno Park appears above the trees on the hill in the background. Small seal with characters “Un-ichi” in reserve on brow, lower right corner. March 5, 1930.

57. ASAKUSA NAKAMISE

58. KUROMON

59. SUKIYABASHI

60. SHIMBASHI

61. EDOGAWA PARK

62. YOYOGI-GA-HARA

63. YAESUGUCHI-DORI

KAWAKAMI SUMI (B. 1895)

Born in Yokohama. Always an experimentalist, Kawakami seems, during the period of the Shin Tokyo Hyakkei, to have been infatuated with the gaudy colors and bold stylization of Matisse, and the designs of Ginza (no. 65), At a Department Store (No. 67) and Theatre at Asakusa (No. 69) were apparently done under a strong Matisse influence. This was a passing phase, however, and there are hardly any traces of it in Kawakami’s later work. He was in his middle 30s when the Shin Tokyo Hyakkei, series was published. He is now living in Utsunomiya. Ref: Onchi (p. 17), Statler (pp. 90-3), Fujikake (pp. 152-3), Oka (p. 11).

64. AOYAMA CEMETARY

65. GINZA (H; 240X180; 0.30). A rather violently colored design of figures strolling on the Ginza, with part of an auto on the left and buildings on the right. The characters “Sumio han” appear on a sign, UR corner. August 7, 1929.

66. EMPEROR’S PARADE

67. AT A DEPARTMENT STORE

68. WASEDA UNIVERSITY

69. THEATRE AT ASAKUSA

70. VIEW OF MARUNOUCHI

71. CHRYSANTHEMUM SHOW, HIBIYA PARK

72. HAMARIKYU PARK

73. FISH MARKET

74. CLOUDY DAY AT MARUNOUCHI

75. AZABU SAN-RENTAI

FUKAZAWA SAKUICHI (1896-1946)

Although Onchi gives the date of his death as 1946, Hiratsuka believes it was January 1947. According to Hiratsuka, in his early years Fukazawa tried to express himself in Western style using mostly oil-based inks. Later he changed to Oriental style and used water-based colors. For several years before his death he designed some excellent book covers. He became a member of Nippon Sosaku Hanga Kyokai in 1928. He was in his early 30s at the time the Shin Hyakkei tokyo, series was published. Ref: Onchi (p. 24).

76. SHIBA ZOJOJI TEMPLE

77. YANAGIBASHI

78. TSUKIJI

79. HAMACHO PARK

80. KIYOSU-BASHI

81. KITOTOGI-BASHI

82. SHIN ARAKAWA

83. SHINJUKU

84. SHOWA-DORI

85. SAKASHITA-MON

86. MEIJI BASEBALL STADIUM

87. KYOBASHI

88. SENJU-OHASHI

SUWA KANENORI (1897-1932)

Hiratsuka, who was a friend of Suwa’s, has written the following about him: “He died in April, 1932. Suwa’s prints have a feeling of poetry, perhaps because he was a great poet all his life. In his early days he used to illustrate a magazine called Roman Letter Zappo, which was published in Kobe. Later this magazine became famous because of Suwa’s beautiful illustrations. He became a member of the Nippon Sosaku Hanga Kyokai in 1928. He worked as a designer for Shiseido, the cosmetics company, until his death. Since he died at such an early age, there are very few prints by him available today.” Ref. Onchi (p. 12).

89. SHIMBASHI EMBUJO

90. HIBIYA PARK

91. MUKOJIMA

92. MARUNOUCHI NAKA-DORI

93. SAKURADA-MON

94. ASAKUSA

95. EDOBASHI

96. FUKAGAWA FACTORY

97. CITY HALL, HIBIYA

98. SHIBAURA

99. NATIONAL DIET BUILDING

100. MARUNOUCHI: TOKYO STATION

REFERENCE BIBLIOGRAPHY

For images of the entire series see MIT's Visualizing Cultures website http://ocw.mit.edu/ans7870/21f/21f.027/tokyo_modern_03/kk_gal_03_thumb.html

The Modern Japanese Print, by Koshiro Onchi, Ukiyo-e Art, No. 11, 1965. (This is a translation of the central portions of Onchi’s book, Nippon Gendai Hanga, Tokyo, 1953.)

Modern Japanese Prints: An Art Reborn, by Oliver Statler. Rutland, Vt., and Tokyo, Japan, 1956.

Japanese Wood-Block Prints, by Shizuya Fujikake, Tokyo, 1938 (rev. ed. 1959)

Notes About the Taisho Print Artists, by Isaburo Oka, Ukiyo-e Art, No. 4, 1963.