Prints in Collection

Himeji Castle, Evening. 1928

IHL Cat. #28

Park in Canton, 1941

IHL Cat. #1013

Biographical Data

Biography

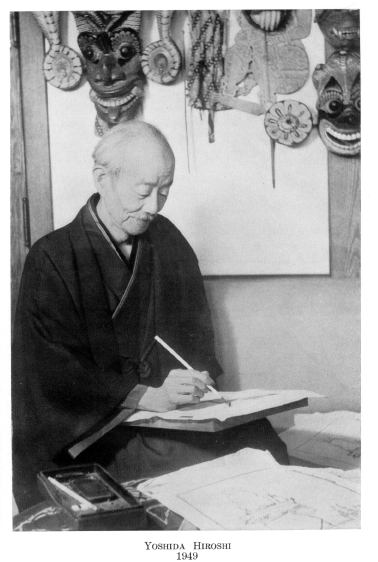

Yoshida Hiroshi 吉田博 (1876-1950)

Woodblocks

In 1920 Yoshida began to design woodblock prints for the publisher Watanabe Shozaburo (1885-1962), who was looking for a Western-style artist to design prints. In September 1923 all the blocks for his prints and existing stock were lost in the Great Kanto earthquake when Watanabe’s shop was destroyed. Soon after he left for the USA once more to raise funds for himself and for others; he toured through the western USA and realized that good prints were eagerly sought after in North America. On his return he set up his own establishment to produce his designs in print form.From 1925 onwards Yoshida devoted his career mainly to prints, supervising all aspects of their production to very high standards. Many of his prints portrayed foreign landscapes and subjects, including the USA and Canada, Europe, Egypt, India (visited 1930-1), and Korea and China (visited 1936). In 1938 he went on the first of three trips to China as an official war artist. He designed his last print in 1946 but continued to paint. He was the prime Japanese organizer of the Toledo Exhibitions in 1930 and 1936, and as a result many of his prints were included: nine were shown in the first and sixty-six in the second. Both exhibitions increased his existing popularity in the USA and led to his being widely collected there. His orientation towards a Western audience is shown in the publication of the book Japanese Woodblock Printing (Sanseido, Tokyo and Osaka, 1939) in English. Yoshida’s sons Toshi (1911-1995) and Hodaka (1926-1995) both became print artists, with Hodaka also working in other print media. Hodaka's wife Chizuko (b.1924) also made prints as did Yoshida’s wife, Fujio (1887-1987).

Experimentation

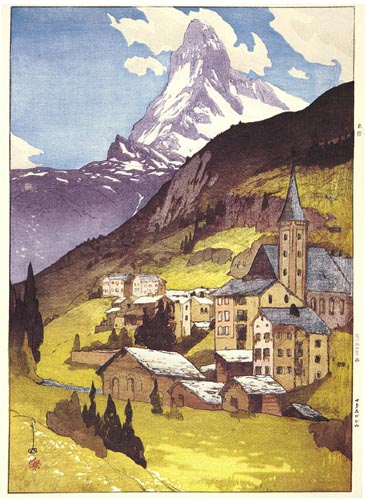

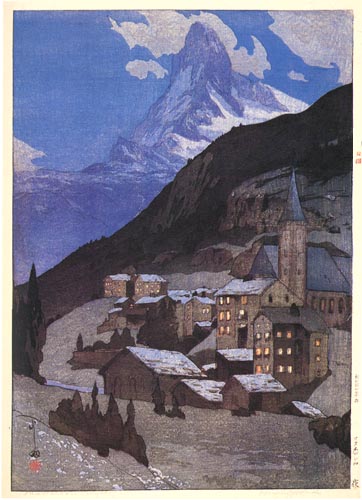

Source: Yoshida Hiroshi: His Personality and Art, Yasunaga Koichi, from The Complete Woodblock Prints of Yoshida Hiroshi, Tadao Ogura, Abe Corporation, 1996, p. 26Yoshida experimented with several art media. In his house were self-created mosaic floors, marble sculptures, inlaid cork pictures, and stained glass windows. His curiosity and experimentation also extended to his printmaking. Sometimes he printed on silk instead of paper and cut blocks from woods other than the standard cherry. He even used zinc plates for intricately detailed parts of fifty or more prints. His inquiring spirit and creativity clearly can be seen in the technique he used to create variant impressions using the same blocks by changing colors, as seen in Matterhorn, Day and Matterhorn, Night below.

Matterhorn, Day 1925 |  |

Death

Source: The Complete Woodblock Prints of Yoshida Hiroshi, Tadao Ogura, Abe Corporation, 1996, p. 193At the age of 73, Yoshida took his last sketching trip to Izu and Nagaoka and painted his last works The Sea of Western Izu and The Mountains of Izu. He became sick on the trip and returned to Tokyo where he died April 5, 1950 at his home. He was buried at Ryuun-in Temple, Kosihikawa, Tokyo.

A Shin Hanga Artist in Control of Print Production Process

Source: A Japanese Legacy: Four Generations of Yoshida Family Artists, LauraW. Allen, Kendall H. Brown, Eugene M. Skibbe, et. al., The MinneapolisInstitute of Arts, 2002, p. 30, 31In making his prints, Hiroshi often likened himself to a conductor or architect, who directed every step of the production. He would say that he needed to have more skills than the artisans he supervised to be able to fully use their talents. The first block carver he employed was Yamagishi Kazue and later Maeda Yujiro, who carved the blocks for most of his prints.

He did not have any specific printers. Not only did he constantly strive to expand his own knowledge of woodblock carving and printing techniques, he was meticulous about the quality of the finished impressions. Only after he was satisfied that a print was unflawed in paper quality, registration, and color did he stamp it with his seal and then sign it in pencil.

In a way, Hiroshi established a third school of modern prints in Japan, combining the artist-carver-publisher system of ukiyo-e with the sosaku hanga artist's total control of the final image. This was one reason why he separated himself from the Watanabe Print Shop, because he realized the supreme importance of the painter in the process. In the Watanabe Print Shop, painters, carvers, and printers had equal input, with the publisher as the ultimate director. But Hiroshi believed that the painter, as the initial creator of the design, should have supreme authority, and that he, as the painter, should supervise the carvers and printers and is so doing also assume the role of director. This why he always printed the notation "self-print" (jizuri) on his works, as a way to distinguish his prints from those of other shin hanga artists.

The woodblock prints produced in this way had the perspectives and compositions of Western-style paintings with the highly refined and precise techniques of ukiyo-e woodcuts. Consequently, Hiroshi was unlike any of the woodblock artists associated with Watanabe, such as Kawase Hasui or Ito Shinsui, who worked in the Japanese style. By taking Western painting into the realm of traditional Japanese woodblock printmaking, Hiroshi opened up a new frontier in Japan that was unprecedented and thoroughly original to him.

Artist's Jizuri 自摺 Seal (self-printed)

The jizuri seal (left) is usually found in the left-hand margin of the print, above the Japanese title and date characters. On a few prints, it is stamped in the right margin or bottom margin.

Prints made after Hiroshi's death do not have the jizuri seal and are considered less valuable then those having the self-printed seal.

Prints made after Hiroshi's death do not have the jizuri seal and are considered less valuable then those having the self-printed seal.