Prints in Collection

Supper Wagon, 1938IHL Cat. #5In a Kyoto Sweets Shop, 1951

IHL Cat. #12

IHL Cat. #202

Fantasy, 1964

IHL Cat. #1140

IHL Cat. #2145

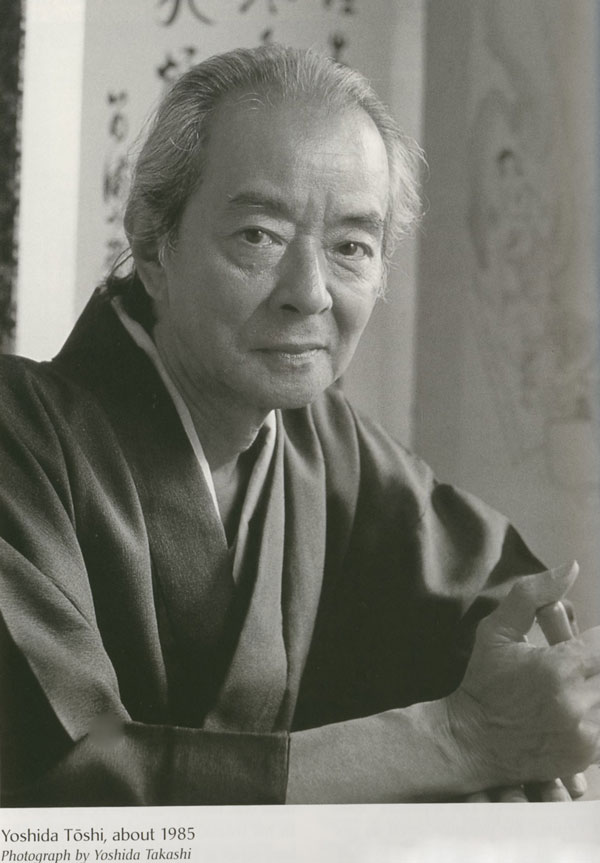

Biographical Data

woodblock | A Turn to AbstractionThe death of Hiroshi in 1950marked Toshi's total (but not permanent) break from his past and naturalism. In 1952, Toshibegan a series of abstract woodcuts, influenced by his brother, HodakaYoshida (1926-1995). In 1953, Toshi traveled to the United States,Mexico, London and the near East. He made presentations in thirtymuseums and galleries in eighteen states. From 1954 to 1973, Toshi madethree hundred nonobjective prints.In Toshi's own words “...itwas an easy – I suppose inevitable – step to abstraction, but it was astep my father could never approve. Still I could not ignore themovement of the times and I began to break away from my formerrealistic approach two or three years after the war.”1 |

1 Modern Japanese Prints, Oliver Statler, Charles E. Tuttle Company, 1956, p.169

The Real Toshi Yoshida

Source: The Real Toshi Yoshida, Pa Kou Vang, St. Olaf College website http://www.stolaf.edu/people/kucera/YoshidaWebsite/evolution/essay_pages/pa_kou_vang.htm and as footnoted.As John Koening, from the movie Space: 1999,once said, “It is better to live as your own man than as a fool insomeone else's dream.” This statement is the issue that Toshi Yoshidahad to face as a developing artist under the influence of his father,Hiroshi. The Yoshida family used a prominent and traditional stylefor their artwork. For many years, Toshi silently protested for freedomto choose what he wanted in his own art. Whether it was the theme ofhis artwork or his personal style, he had to go through his fatherfirst. Hiroshi was a demanding father wanting to shape Toshi’s artinto a second-generation version of his own, but Toshi secretly opposedthis pressure by avoiding the romanticism that exemplified hisfather’s work, and choosing subjects different from his father’slandscapes.

The Yoshida family is almost a one-family artmovement. The first artist in the Yoshida family line was KosaburoYoshida; he went to a western art school, and his incredible workdemonstrates the Italian influence in Japanese art. Kosaburo only haddaughters, and among them was Fujio, who was also a talented artist. Nevertheless, Kosaburo adopted as a son whom later became his son inlaw, the promising young man who became the famous artist HiroshiYoshida. Hiroshi worked primarily as a painter until his late fortieswhen he became fascinated with woodblock printing. Fujio and Hiroshihad two sons, Toshi and Hodaka, who carried on the family’s artisticline.

Toshi was born on July 25, 1911 just two monthsbefore his older sister Chisato, a three year old girl passed away. Forthe next fifteen years Toshi lived a lonely life, for he was the onlychild, until his brother Hodaka was born. According to Hiroshi’s plan,Toshi would become the artist, while Hodaka was meant for a career inscience. Sadly, when Toshi was a child he contacted polio meningitisfrom his nanny’s family, which paralyzed one of his legs. This tragicincident played a big role in Toshi’s life as an artist because as ayoung boy he was not allowed to play outside with other children. Thus, Toshi spent his free time making art and inventing animalstories. According to Kendall H. Brown, “Toshi also routinely sketchedwith his parents, who taught him the rudiments of life drawing”1.Toshi was taught at an early age the beauty of art.

Toshiwas the individual that Hiroshi would most deeply imprint with hissense of natural beauty and light. Kendall H. Brown mentioned thatHiroshi was Toshi’s teacher and ‘most ardent critic, sought to moldToshi and his art into a second-generation version of himself and hisown highly successful naturalism’. This explains why most ofToshi’s artwork is similar to his father’s because Hiroshi wanted Toshito fellow his technique. Still, it was hard for Toshi to please hisfather while trying to find and maintain his own identity. Toshi oncestated that he chose to put his interest in animals because hisfather’s interest was in landscape; this was a way to differentiate hiswork from his father’s. Kendall H. Brown stated that, “viewers who arefamiliar with Hiroshi’s naturalistic landscapes often see Toshi as anartist who never fully emerged from his father’s shadow”. Perhapsit is that Toshi often painted and made prints of many of the samesubjects that Hiroshi used.

Itwas not until Hiroshi’s death in 1950 that Toshi could really breakaway from his father’s demands. In order for Toshi to break away fromhis father’s naturalism and his past, he resigned from his father’sPacific Painting Society to join with his brother Hodaka's group called Plus. Toshi moved into abstract art because his brother Hodaka, who had alsobecome an artist, influenced him. Abstract art was a new and differentstyle to Toshi. Therefore, he found himself within abstraction.

AlthoughToshi Yoshida was strained to become the second-generation version ofHiroshi, his father, he eventually broke away by secretly avoidingromanticism and purposefully contradicting his father’s artisticvalues. Toshi opposed his father through his artwork with hisindependent values of what was important to show his audience. Theresult was a unique type of art where Toshi’s true character came out.

1 All Kendall H. Brown references from A Japanese Legacy: Four Generations of Yoshida Family Artists, LauraW. Allen, Kendall H. Brown, Eugene M. Skibbe, et. al., The MinneapolisInstitute of Arts, 2002, p. 72-73.

Collections

Source: Collecting Modern Japanese Prints, Then and Now, Mary and Norman Tolman, Charles E. Tuttle Company, 1994, p. 246Sydney Museum, Australia; New York Museum of Modern Art; Boston Museum of Fine Arts; Cincinnati Art Museum; Art Institute of Chicago; Tokyo National Museum of Modern Art; MOA Museum, Atami, Japan; British Museum, London; Portland Art Museum; Paris National Library, National Museum of Australia, Canberra; Seattle Museum of Art; Krakow National Museum; Los Angeles County Museum of Art; and others

Pencil vs. Printed Signatures on Toshi's Prints

Source: Shin Hanga website December 2000 anonymous posting http://shinhanga.net/flotsam2.htmAlthough the Yoshida's have not yet found their way to ShinHanga.net, I had a recent discussion about Toshi's pencil and block signatures with Eugene Skibbe, the author of the book Toshi Yoshida - Nature, Art and Peace. He provided me with an interesting statement from Takashi Yoshida, number 2 son of Toshi. "The fact is, that already during the lifetime of Toshi some prints got the printed signature instead of the pencil signature."

Due to hospitalization and the weakness of his hand, Toshi Yoshida (1911-1995) chose to use a hand printed signature with embossed seal during this period. However, he kept supervising all of the printing at his studio. So, you may find the following signatures for his prints:

1. Original Limited number with his pencil signature.

2. Original Limited number with printed signature with embossed seal.

3. Posthumous Limited number with printed signature without embossed seal.

4. Original Unlimited number with his pencil signature.

5. Original Unlimited number with printed signature with embossed seal.

6. Posthumous Unlimited number with printed signature without embossed seal.

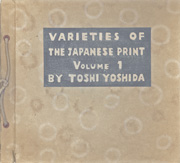

Literature

A Japanese Legacy: Four Generations of Yoshida Family Artists, Laura W. Allen, Kendall H. Brown, Eugene M. Skibbe, et. al., The Minneapolis Institute of Arts, 2002 (Produced in conjunction with the exhibition "A Japanese Legacy: Four Generations of Yoshida Family Artists," held at The Minneapolis Institute of Arts from February 2 to April 14, 2002.Modern Japanese Prints 1912-1989, Lawrence Smith, British Museum Press, 1994, p. 39

Modern Japanese Prints: An Art Reborn, Oliver Statler, Charles E. Tuttle Company, 1956. p. 168-169.