Biography

Family name: Ishiwata or, possibly, Ishiwatari1

Given name: Shōichirō 庄一郎

Artist names: Kōitsu 江逸; Yoshimi 芳美よしみ; Shōichirō 庄一郎 and Tōkō 東江 or 東光2

Born in Shiba, Tokyo into a family of kimono designers, Ishiwata’s given name was Shōichirō 庄一郎, a name that would appear on many of his prints for the Tokyo publisher Katō Junji 加藤潤二 later in his career. After graduating from primary school he studied design, fabric dying and nihonga painting under his brother-in-law, the kimono designer Igusa Senshin, who had studied under the ukiyo-e artist Utagawa Kuniyoshi.3 His first recorded job was as a textile designer for the Yokohama department store Nozawaya which he joined following the 1923 Great Kantō Earthquake and where he won “considerable recognition” for his designs.4 He worked there until 1930 when he left to design prints for Watanabe Shōzaburō (1885-1962), the publisher who birthed the shin hanga genre.

While Ishiwata’s brother-in-law may have introduced the techniques of traditional woodblock design to him, his long association with the shin hanga designer Kawase Hasui (1883-1957) must have been instrumental in Ishiwata’s changing of career paths at the age of 33. First meeting in 1917, the year Hasui was approached by Watanabe to design some experimental landscape prints for him, the two artists must have maintained contact throughout the 1920s, as it was Hasui who recommended that Ishiwata come to work for Watanabe in 1930. While a catalog published by the Yokohama Museum of Art states that Ishiwata “became an earnest student of Kawase” in 1930, I imagine he became one of the introspective Hasui’s few students prior to that date.5 Certainly Ishiwata’s first prints for Watanabe, released in 1931under his artist’s name of Kōitsu 江逸,were stylistically heavily influenced by Hasui. Ishiwata would design prints for Watanabe until 1935 when both he and Hasui started creating designs for the Tokyo publisher Katō Junji. While Hasui would return to Watanabe, Ishiwata may have finished his career with Katō, although he would work with several other publishers along the way such as Doi Sadaichi (using the art name Tōkō) and Kawaguchi.

For an artist who seemingly dedicated his career to printmaking after 1930, surprisingly few prints, less than fifty, have been identified as being designed by the artist with the bulk of those published by Watanabe (approximately 25) and Katō (approximately 10). I imagine that in the coming years more of his prints may well be discovered.

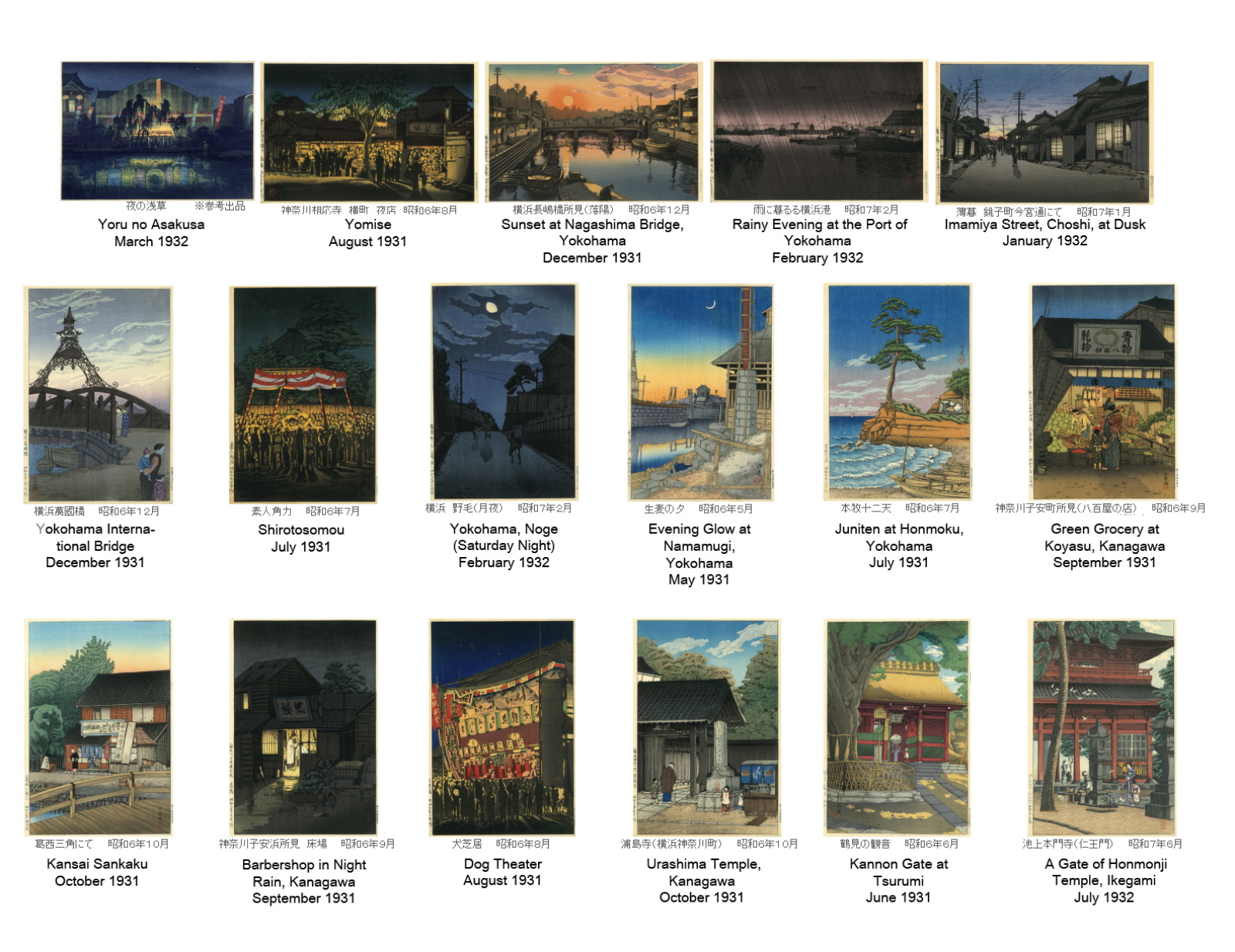

Seventeen of approximately twenty-five designs for the publisher Watanabe Shōzaburō

Many of the artist's designs were landscapes employing settings in and around Yokohama, an area he was intimately familiar with, but he also created a series depicting toys [Collection of Pictures of Toys (Omacha eshū), ca. 1935] and a series showing various hot-spring resorts [Hot Spring Landscapes (Onse fūkei), ca. 1940.]6 His handling of light has been compared to that of Inoue Yasuji (1864-1889) a pupil of Kobayashi Kiyochika (1847-1915), considered the Meiji-era master of light and shadow.7 Smith states that Ishiwata’s “subtle, dark and low-key subjects seem not to have been successful with Western customers, and around 1935 he switched to working with Katō Junji” who is described as being “more receptive” to Kōitsu’s work.8 [I imagine that Kōitsu’s move was also influenced by Hasui’s starting to design prints for Katō in the same year.] While working for Katō, Ishiwata would occasionally combine stenciling techniques with woodblock, certainly a throw-back to his textile design days.9

With the exception of several prints published by Katō in 1950, I was not able to find any information on Ishiwata’s activities after WWII, although additional research may reveal more about the artist’s later activities.

Samples of the Artist's Signatures and Seals  Kōitsu 江逸 seal Kōitsu 江逸 seal |  |  Kōitsu 江逸 with Kōitsu seal |  Shōichiro 庄一郎 with Shō seal |  芳美画 |  | Tōkō 東江 with Shō 庄 seal |  |  庄一郎 |

1 The British Museum website http://www.britishmuseum.org/research/search_the_collection_database/term_details.aspx?bioId=147386