| |

| New Year's Outing Before a Suspension Bridge, 1877 IHL Cat. #493 | The seventh month: Suketakaya Takasuke IV from the series Famous Views for the Twelve Months, 1882 IHL Cat. #688 |

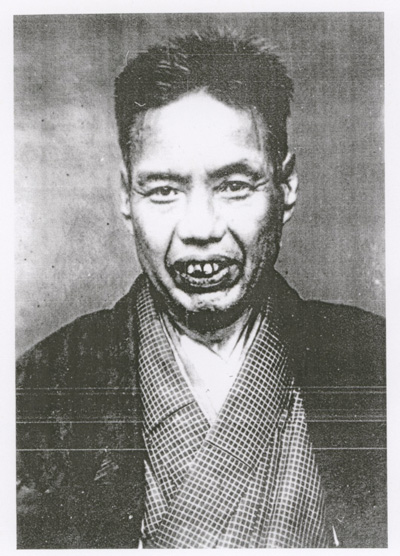

Photograph of Kyosai (undated) | ProfileKawanabe Kyōsai 河鍋暁斎 (1831-1889) Source: Kawanabe Kyosai Memorial Museum websitehttp://www2.ocn.ne.jp/~kkkb/ENG/about.htm This great artist has grown in stature as we have been able to better get the Meiji period (1868-1912) into perspective. He studied at an early age under Kuniyoshi (1798-1861) and later under Kanō masters, but eventually he went his own independent way. Essentially a nationalistic painter, he was nonetheless fully aware of Western art - indeed, he dealt with it quite broad-mindedly in his book Kyōsai Gadan published in 1887 - but he was robust enough not to succumb, as so many of his contemporaries did, to the blandishments of foreign styles, and was one of the last great painters in the truly Japanese tradition. If he has a fault, it is over-exuberance: he paints vigorously with a full brush, but his immense bravura and skill are sometimes a little overpowering. But this very impetuousness and daring is often more economically used in smaller sketches and drawings and they have always elicited greater Western praise than many of his more important works. Kyōsai, because of the warmth of his personality, his eccentricities and his known love for sake over and above his gifts as a painter, was a legend in his lifetime, and by great good fortune we have two intimate Western accounts of him at work: one by Emile Guimet (1836-1918), who with Felix Regamy, visited him in Japan in 1876, and wrote about him in Promenades Japonaise, published in 1881; the other by Josiah Conder (1852-1920), the British architect, who studied painting under Kyōsai in the 1880s, and who, in his Paintings and Studies by Kawanabe Kyōsai, published in 1911, gave a very full account of the artist's methods. ---- (Jack Hillier) |

Biography

Kawanabe Kyōsai 河鍋暁斎 and 河鍋狂斎 (1831-1889)Sources: Comic Genius: Kawanabe Kyōsai, Oikawa Shigeru, Clark Timothy and Forrer Matthi, Tokyo Shinbun, 1996;

Demon of Painting: the Art of Kawanabe Kyōsai, Timothy Clark, British Museum Press, 1993

Kyōsai was born on the seventh day of the fourth month, Tempo 2 (1831) to Kawanabe Kiemon (Kawanabe Nobuyuki 河鍋陳之), a samurai retainer of the Koga fief. He was given the childhood name Shūzaburō (周三郎). In 1832 his family moved to Edo where his father purchased the samurai family name Kai, and joined the official firefighters to the Shogunate.

Early Training

Showing an early ability for sketching, he began his formal artistic training in 1837, at the age of six, when he entered the school of the famous ukiyo-e artist Utagawa Kuniyoshi (1798-1861). The two years he spent studying with Kuniyoshi are considered seminal. In 1840 he entered the studio of the Kanō painter Maemura Towa (?-1841) who gave him the nickname "Shuchu gaki" (“Demon of Painting”). (Gaki is a pun on the ‘hungry demons’ of medieval Buddhism and also the word ‘kid’). The name stuck and became a persona proudly promoted by Kyōsai in many of the seals he used to the end of his career. In 1848 he progressed to the studio of Kanō Tohaku (?-1851), head of the Surugadai branch of the Kanō school and completed his first known work, Bishamon. In 1849 he completed his formal studies and was given the art name Kanō Tōiku Noriyuki.During his time in the Kanō school Kyōsai discovered his taste for sake and visiting brothels.

Pursuing an Independent Career

Following graduation he was adopted by Tsuboyama Tozan, painter to the Akimoto fief, but they parted ways at the end of 1852 due to Kyōsai’s dissolute behavior. In 1854, after the deaths of his earlier instructors, he severed the link with the Kanō school and established himself as an independent artist, although for the rest of his life Kyōsai revered both Kuniyoshi and his Kanō teachers. It is reported that he visited the Surogadai Kanō school regularly around 1859 to receive further training. His early independent career was founded on his development of the genre known as kyōga (‘crazy pictures’) – from which his own name Kyōsai derived.The year Kyōsai left the Kanō school to pursue an independent career, 1854, saw the Shogunate forced to sign a treaty with Commodore Matthew Perry opening diplomatic relations between Japan and the outside world under threat from eight US warships in Edo Bay.

In 1857 he married the first of four wives, Okiyo, established a shop at Hongo Daikonbata and succeeded to the Kawanabe name. He began to use the gō (artist name) Seisei Kyōsai 惺々狂斎 and paint kyōga in the style of Toba Sojo. The fundamental meaning of the character sei, repeated twice in Seisei, a name Kyōsai would use for the rest of his life, is ‘enlightenment’. Kyō means ‘wild’ or ‘crazy’, and the name Kyōsai (‘Crazy Studio’) is clearly linked to his production of kyōga.

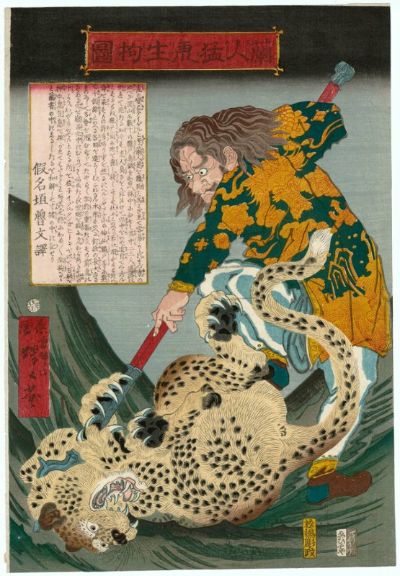

Kyōsai’s earliest-known group of color prints are the several designs he did for the publisher Ebisuya of a leopard, thought to be displayed in Japan in the summer of 1860.

In 1860 his son Shōzaburō was born, followed by the death of his second wife and his father and in 1861 his elder brother died.

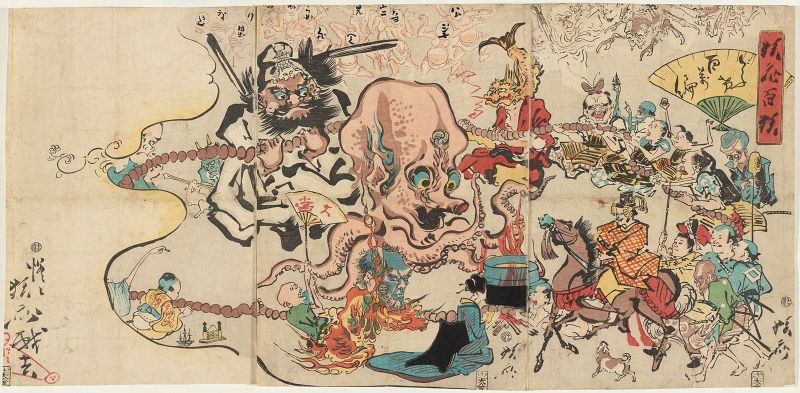

The year 1863 saw the start of Kyōsai's major period of woodblock production creating close to sixty designs that year, including works for the Go-jōraku Tōkaidō (Gyōretsu Tōkaidō) series which treated the Shogun’s visit to Kyoto and for the kyōga series Kyōsai hyakuzu (One Hundred Pictures by Kyōsai) [represented by a number prints in this collection.] He would go on to collaborate with Kunisada and other artists on print designs, supply designs for novels, and contribute to the album A Journey Around Hell and Paradise.

Arrested for Satire

In October 1870, Kyōsai was arrested after taking part in a shogaki held by the haiku poet Kikakudo Ujaku at a restaurant on the banks of Shinobazu Pond at which he got very drunk and painted works that satirized the authorities. He was held in detention for several months and then sentenced to fifty lashes in January 1871. Kyōsai gadan says the works in question showed shoes being put on inhabitants of the island of long-legged people and inhabitants of the island of long-armed people pulling hairs from a large statue of the Buddha – both of which were interpreted as satirizing officials’ sycophancy towards foreigners.After his release Kyōsai changed the first character kyō of his name from ‘crazy’ to one meaning ‘dawn’ or ‘enlightenment’. For health reasons, he was not able to begin working again until the end of 1871.

Contact with Famous Westerners

When Westerners came into the country, Kyōsai came into contact with several of them including Ernest Fenollosa, the American art historian of Japanese Art who helped found the Tokyo School of Fine Arts and the Tokyo Imperial Museum. Two foreigners who became especially important in documenting Kyōsai's life were Emile Guimet and Josiah Conder. Emile Guimet visited him in 1876 in Japan and later wrote his memories down in an essay titled Promenades Japonaises and the British architect Josiah Conder (1852-1920), who became his student in 1877 and documented Kyōsai's life and works, and who stayed with Kyōsai until his death in 1889. In 1911, after returning to England, Conder wrote Paintings and Studies by Kawanabe Kyōsai which contributed to Kyōsai's growing fame overseas.Reminiscences by Westerners

Studying a Severed HeadSource: “Some Phases of Japanese Art.” Leon Mead, appearing in The Craftsman, Volume III: October 1902-March 1903, United Crafts

Mrs. Hugh Eraser, in her delightful Letters from Japan, states that Kyōsai at nine "captured the severed head of a drowned man from a swollen river, and brought it home to study in secret, as any other child would treasure a toy or a sweetmeat. The horror was discovered by his family, and he was ordered to take the grisly thing back to the stream and throw it in. Reluctantly the little boy trudged back to the river bank, the poor head in his arms; but before he threw it away, he spent long hours, sitting on the ground, copying every line of the awful countenance." Other curious stories are told of his early passion for drawing and of the many ways in which he justified his later reputation as one of the greatest artists Japan has produced.

A Charitable Man

Source: Japan, The Place and the People, George Waldo Browne, Dana Estes & Company, 1901, p. 394.

Though he received large sums for his work, he gave it nearly all to the poor. He could bear to see no one suffer while he had a crumb to give. At one time he was stopping at one of those pretty little wayside inns so common in Japan, and called there tea-houses, which was kept by a poor widow. On that day she was feeling especially unhappy, having just been ordered to give up the house for an old debt. No sooner had she told this than the artist began to cover the stainless paper walls with grotesque figures and strange images. Alarmed at the disfiguration of her house, the frightened woman begged him to stop, and finding her protestations useless, she called upon others to take the madman away. But her entire demeanor changed at the whispered utterance of the name "Kyōsai," and her joy knew no bounds as she saw him cover with his matchless brush not only walls but ceiling. She realized enough from the sale of those walls to pay all her debts and leave her a comfortable sum besides.

Display of His Work Abroad

His work was exhibited at the Vienna International Exposition in 1873 and at the Exposition ofParis in 1883.

Death and Summation

The year Kyōsai died, 1889, saw the promulgation by the Emperor of a new constitution, instituting a conservative system of representative democracy modeled on Imperial Germany that was designed to demonstrate to the USA and European powers that Japan was now ‘civilized’ and worthy to join their ranks.Kawanabe Kyōsai was a drinker and a genius, a painter and printmaker of the weird, the comic and the obscure. He belonged to the generation of ukiyo-e artists in transformation from the Edo to the Meiji period, from the Middle Ages to a Modern Industrialized Society.

Kawanabe Kyōsai was an eccentric who exaggerated everything he did - from his consumption of sake wine to his painting and printmaking style. With his fellow artists Kunichika and Kobayashi Kiyochika (1847-1915), Kyōsai frequently went on drinking binges. Like Kunichika, he was great in inventing great stories.

The output of Kawanabe Kyōsai's creativity was enormous. At the end of his life, he had produced hundreds of paintings, prints and illustrated books.

The paintings and print subjects of Kyōsai range from traditional to bizarre and fantastic. His drawing style was unique and at the same time he was capable of painting in the finest traditional style of an 18th century painter. Many of his designs are comic, satiric, humorous and sketchy. Others are strange, weird and frightening. He had a lively interest in Western art, but was never interested in imitating it.

In August 2000 a painting by Kawanabe Kyōsai on a two-fold screen was hammered at 400,000 British Pounds at Christie's in London, the highest price everpaid for a painting of the Meiji era.

Kyōsai Woodblock Prints

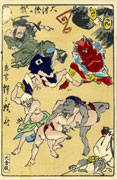

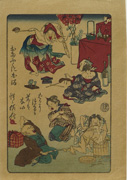

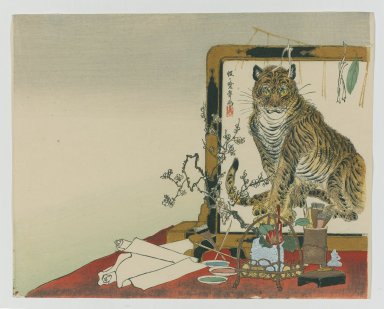

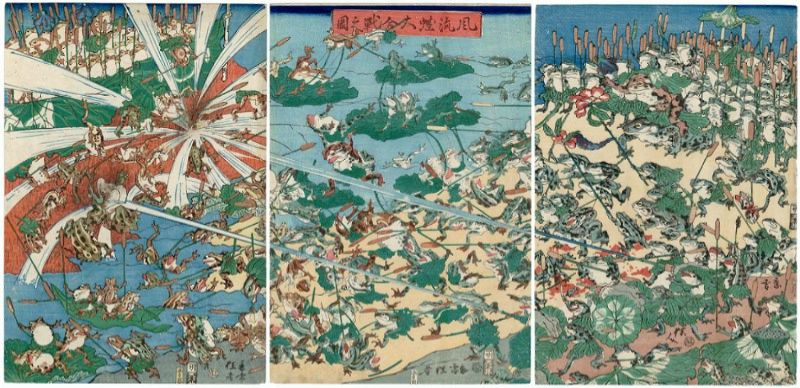

A Dutchman Capturing a Ferocious Tiger Alive 1860 |  Standing Screen of a Tiger 1878 |  Cartoons, date unknown |

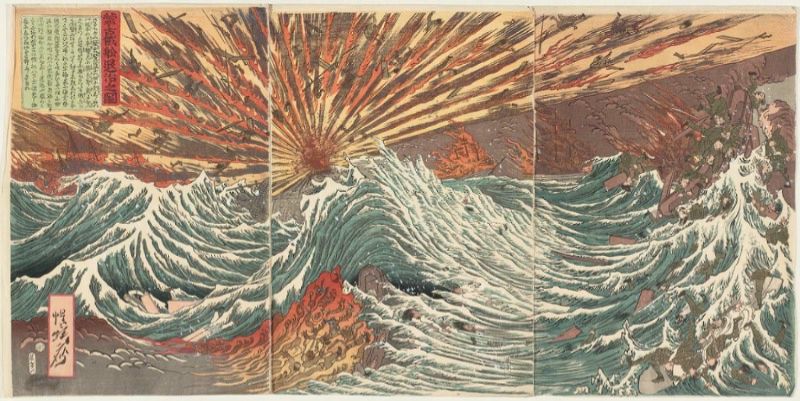

1864 |  Repelling the Mongol Pirate Ships 1863 |  Comic One Hundred Turns of the Rosary 1864 |

Kyōsai Gadan (暁斎画談), or "Kyōsai's Treatise on Painting"

(an autobiographical painting manual)

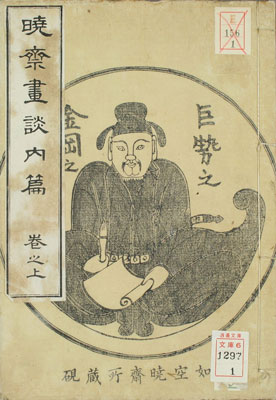

Issued in four volumes with each volume approximately 27.4 x 17.5 cm.

Source: Copying the Master and Stealing His Secrets: Talent and Training in Japanese Painting, Brenda G. Jordan and Victoria Weston, University of Hawaii Press, 2002, p.95-102.

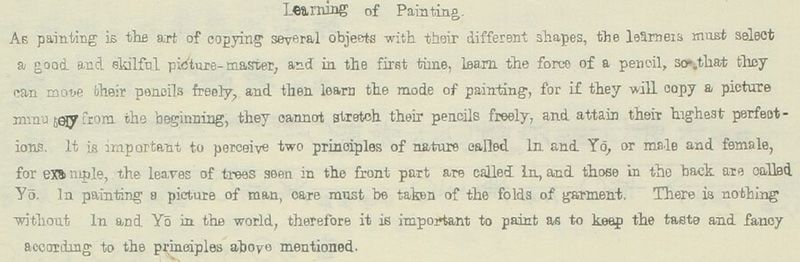

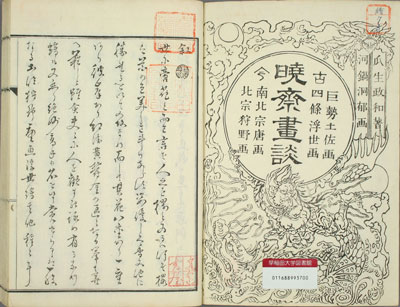

Kyōsai embraced a pedagogy that included the essential elements of copying and studying the works of former painters. His preface to the Kyōsai gadan of 1887 begins with the words, “Wanting to understand both old and new masters, I copied down any genuine major work that caught my eye.” Later in the same preface, he continued, “The most important part of this book is to show to beginners of the younger generation the essentials of brush technique [hitsui] of famous masters of past and present, and, in addition, to cause the development of their own technique [dokuji no gijutsu], ultimately allowing them to master a skill that surpasses the men of old.”

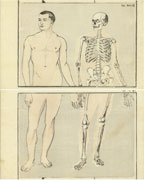

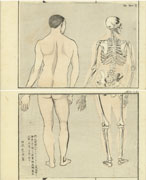

Kyōsai wanted his students to see the larger picture involved in a life devoted to painting – the inseparable character of one’s personality and one’s art, the importance of shasei (drawing from nature), the study of old and new masters, training in brush techniques, and, ultimately, the development of one’s own style. This manual for aspiring students contains some 165 illustrations, 66 in the biography portion and 99 in the painting manual. The manual uses the writing of the Kyoto Kanō painter Eino (1631-1697) as a source for the section “Learning to Paint.” Initial illustrations in this section begin with samples of Kanō brushwork and examples of the work of Kanō painters are included throughout, particularly the paintings of Kanō Tan’yu. However, the Kyōsai gadan also freely draws on sources from nearly all schools of Japanese painting for this purpose, from medieval times to the nineteenth century, in addition to Chinese and Western examples.

Among the copies from foreign sources is the figure of Lacoon struggling with serpents (see IHL Cat. #298), based on an image of the marble sculpture Lacoon and His Two Sons in the Musei Vaticani, Rome. (The sculpture may date anywhere from the second century B.C. to the first century A.D.) In Kyōsai’s copy, the figure is bald and drawn with the major muscle groups revealed as if it were a type of anatomical study. Examples of the work of Japanese painters range from the Muromachi ink painters Bunsei (fl. mid-fifteenth century) and Shubun (fl. 1414-1463) (see IHL Cat. #299)to Maruyama Okyo, Nagasawa Rosetsu (1754-1799), and Kitagawa Utamaro (1753-1806).

Beginning with the fourth illustration, Kyōsai offered his readers a series of anatomy drawings showing the alignment of muscles or the underlying skeletal structure of the human body. (See Kyōsai Gadan, Anatomical Drawing of Front Facing Man IHL Cat. #297 and Kyōsai Gadan, Anatomical Drawing of Rear Facing Man, IHL Cat. #298.)

The publication of painting manuals was a quite well-established practice by the 1880s. However, the Kyōsai gadan was unusual in several respects. First, the compilation of an autobiographical text and painting manual that contained a special focus on personal revelations was uncommon. Second, the book includes text in English on how to paint, including a description of colors. A note at the end in Japanese states that part of the text is based on the writing of Kanō Eino, as mentioned above; however, the accompanying English text inexplicably substitutes the name of Nishikawa Sukenobu (1671-1751), an ukiyo-e painter who had been a pupil of either Eino or his son Eikei (1662-1702). Finally there is information, or rather advertisement, on where one could purchase painting materials. As the Kyōsai gadan was published for public consumption, interested parties could take advantage of the examples and advice presented and use the book for personal study.

Thus, the Kyōsai gadan amplified the tradition of woodblock-printed painting manuals, following the idea of a copybook but also including a wealth of new types of material The gadan presents to the reader the story of one man’s passion for painting but also delivers a theoretical foundation on which students should base their studies. Shasei is to be attended to first and practiced often, but the pupil should also focus on brush technique and works by well-known painters and print designers. The manual was meant to be a tool for achieving technical excellence but with the end in mind that the student would strive to develop a superior, and clearly personal, technique.

Cover of Volume 1 Cover of Volume 1 |  Inside Front Page |

click to enlarge

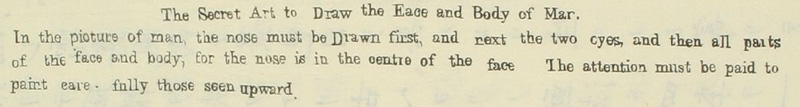

English translation appearing in Volume 1

Obituary

Source: Kawanabe Kyōsai Research Community website http://kyosai-en.blogspot.com/2006_05_01_archive.htmlMay 18, 1889, The Japan Weekly Mail, p. 477-479

KYŌSAI [communicated] [by Josiah Conder]

“KAWANABE KYŌSAI died on the evening of the 26th (April). In him Japan has lost a great painter, undoubtedly the most talented of his time. What the studied writings of the polished author are to the inspired uttering of the born orator, such were the most successful works of other painters of his day compared with the marvelous conceptions and vigorous creations of this powerful artist.

A patient student of nature and reverential copyist of all that was worthy in the works of the past, his own productions always bore the impress of originality and genius. Of Kyōsai it may be truly said that from birth to death he was a devoted servant of the painter's art. His first infant efforts with the brush were made with nature as his model.

Three days before he died the desire to paint once more seized him irresistibly, and he sketched upon the paper slide behind his bed a weird outline of his own emaciated form bent and tottering as he stood to paint, and suffering from the symptoms of his fatal disease. A few straight lines below the knees, suggesting too plainly the square shell in which he was soon to be enclosed, showed that he knew well this sketch would be his last. Heartrending and horrible, shaky and imperfect, these touches contain some of the genius of Kyōsai. In their own weird way they tell the story of his untimely death: and where in the history of all art has such a story been so briefly, and strangely expressed? But a short time before his spirit departed, and after he had been barely able to utter a few feeble words to his wife and children, with an agonizing cry and almost supper natural effort he called for his old kyoji-ya, and gave him instructions about the mount of one of his latest works. Thus his last despairing struggle was that of severance from the art he loved.[・・・]

From force of education a follower of the methods and many of the conventions of his native art as practiced by his great predecessors, Kyōsai never considered that this art had attained its final limits. He regarded with unlimited respect the scientific knowledge of anatomical form, perspective and sciography revealed to him in foreign works and the more realistic developments of nature painting and landscape as developed in the West. To him there always existed a great El Dorado of art beyond the limit of the lights into which he was born and within the radius of which his own opportunities compelled him to work.

In the rules which he laid down for the guidance of his pupils he first insisted upon a careful and attentive copying of natural life. The small garden of his studio was filled with all manner of animal, bird, fish, and insect life. Copying from nature he called the foundation or basis of painting and the mannerism of the touch an ornamental adjunct equally necessary though secondary in the art. He urged also the study of photographs and oil paintings as an aid to correct and faithful representation; but nature was in all cases to be the first master.

Such faithful copies from nature were to be regarded simply as studies and as aids to observation and memory. With a mind and memory well stored with all natural forms, and a hand skillfully trained to the production of powerful and expressive lines, the painter, seeking inspiration, would produce extempore his best works. Slavish copying for reproduction of the ideas of former painters he condemned, and though regarding many of the past artists of the old schools with profound reverence, he considered those schools as now dead all but in name, and represented only by powerless slaves to method and indifferent imitators. His independence of character and versatility had long severed him from the outward conventions of a school of which the letter and not the spirit remained. Modest to the degree of humility, and full of veneration for talent, he found but little in contemporary art to venerate, and lived alone as a painter in the society of his own powerful conceptions and in communion with the past great spirits of art whose closer company he has now joined.“

Josiah Conder the British architect, designer of the Ueno Museum, who studied with Kyōsai for the last eight years of Kyōsai's life, was at his bedside when he died of stomach cancer.1 He is buried in Zuirin-ji Temple, Yanaka Tokyo.

1Demon of painting: the Art of Kawanabe Kyōsai, Timothy Clark, British Museum Press, 1993, p. 29

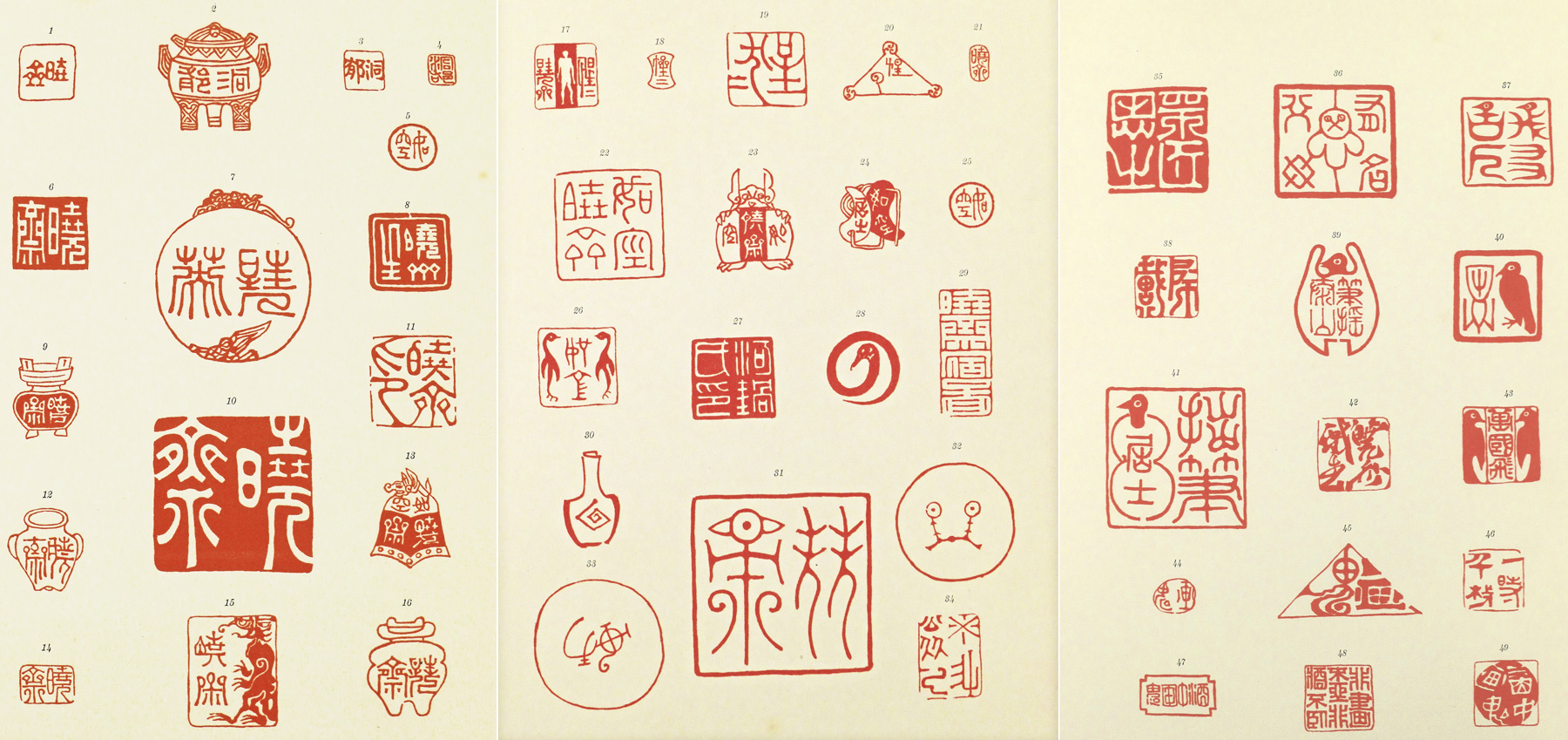

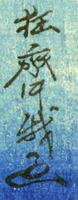

Kawanabe Seals, Art Names and Signatures

Seals as pictured in Paintings and Studies by Kawanabe Kyosai by Josiah Conder1

(images taken from the collections of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston and the British Museum and this collection)

Kyōsai Kyōsai狂斎 |  Kyōsai 狂斎 |  Kyōsai gi Kyōsai gi狂斎戯 |  Kyōsai gi Kyōsai gi狂斎戯 |  Kyōsai giga Kyōsai giga狂斎戯画 |

惺々暁斎 |  惺々暁斎 |  惺々暁斎 gaki 画鬼 seal |  惺々暁斎 gaki 画鬼 seal |  惺々暁斎 gaki 画鬼 seal |  惺々暁斎 unread seal |  惺々狂斎画 unread seal |

惺々狂斎 |  惺々狂斎 ? Seisei ?惺seal |  惺々狂斎 with Jokū Kyōsai 如空暁斎 and Kyōsai 暁斎 seals |  惺々狂斎 unread seal |  惺々狂斎画 unread seal |

惺々狂斎 |  |  惺々暁斎 stylized seal |  惺々暁斎 Kyōsai gaki 暁斎画鬼 seal |  惺々狂斎 入堂 Seisei Kyōsai 惺暁 seal |  惺々狂斎 Tōiku 洞郁 seal |

unread seal |  惺々狂斎戯画 with triangular shaped sealed and characters reading Seisei (惺々) |  応需 惺々狂斎 Seisei 惺々 seal |  応需 惺々狂斎 Seisei 惺々 seal |  ōju Seisei Kyôsai 応需惺々狂斎 triangular shaped sealed Seisei 惺々 |

ōju Kyōsha 応需狂者 |  応需惺々暁 triangular shaped sealed Seisei 惺々 |  応需惺々暁 |  応需惺々暁斎 |  応需惺々狂斎 |  応需狂惺々 |  応需惺々暁斎 |

応需惺々暁斎 |  應需惺々暁斎 Seisei Kyōsai 惺二暁斎 seal 二 used in place of 々 |  如空暁斎図 Bankoku tobu 萬國飛 (with crows) and Jokū 如空 seals |  惺々狂斎洞郁 triangular shaped seal Seisei 惺々 |

Chikamaro 周麿 |  応需周麿 |  応需周麿 |  応需周麿 |  応需惺々周麿 |  応需惺々周麿 |

Kawanabe Kyosai Memorial Museum

Source: Kawanabe Kyosai Memorial Museum website http://kyosai-museum.jp/ENG/about.htmThe Museum houses over 3,000 of Kyōsai's preparatory drawings and studies.

ABOUT KAWANABE KYOSAI MEMORIAL MUSEUM

Welcome addresses of the director and about the museum:

I am pleased to have your visit to marvelous arts of Kyosai Kawanabe, my great-grandfather and one of the most talented painters in the latter half of the 19th century in the world. The Kawanabe Kyosai Memorial Museum was established in 1977, based on the collection of Kyōsai's drawings and paintings along with his daughter Kyosai's works. I believe the revaluation of Kyōsai is sure to open up a new field in Japanese art; he has hitherto been unduly depreciated as merely eccentric by narrow-sighted art historians.

Recent Exhibitions

The British Museum: "Demon of Painting: The Art of Kawanabe Kyosai" (December 1, 1993 - February 13, 1994)

Source: The Independent website http://www.independent.co.uk/arts-entertainment/exhibitions--crazy-like-a-badger-the-japanese-demon-painter-kawanabe-kyosai-overindulged-in-sake-for-arts-sake-iain-gale-inspects-the-damage-1406806.html

Iain Gale inspects the damage by Iain Gale, Friday, 14 January, 1994

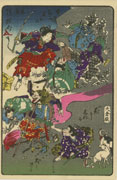

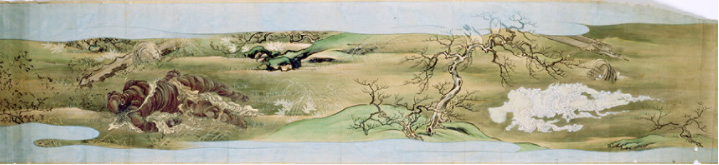

Atabout 11 o'clock in the morning on 30 June 1880, the renowned Japanese painter Kawanabe Kyōsai started work on his great curtain for the Shintomi theater. It was to be a version of the classic subject the One Hundred Demons, and as Kyōsai wielded his huge painting broom, their faces began to take shape. But there was something different about them. These were not the elegant forms of the ukiyo-e painters. They were wild-eyed, manic creatures who moved across the picture in a frenzy of diabolical abomination. The writer Kanagaki Robun, who happened to be watching, remarked pithily that this was kyōga, 'crazypainting'. And he wasn't wrong. His old friend Kyōsai was quite drunk. Since 10 o'clock that morning he had downed three bottles of sake. That wasn't bad going, even for a man whose personal daily intake of 1.8 litres of the powerful rice wine was delivered to his house every morning. Sake was vital to Kyōsai's art and under its spell he produced the most extraordinary works of his 35-year career, many of which are currently on view at the British Museum. According to his pupil, the English architect and traveler Josiah Conder, while 'under the influence of Bacchus some of his strangest fancies, freshest conceptions and boldest touches were inspired'.

Kyōsai was the wild-man of 19th-century Japanese art and fully deserved his sobriquet Shuchu gaki (demon of painting). He is recorded as having assaulted fellow artists and in 1870 was imprisoned for his scurrilous depictions of western visitors. While his contemporaries of the Meiji period chose to depict the elegant society of ukiyo-e, the 'floating world', Kyōsai plumbed the depths of his own drink-addled mind to create a fantastic menagerie of animals, ghosts and demons which rivals the most excessive grotesqueries of Disney's Fantasia or Marvel comics.

Born in 1831, the son of a rice-merchant turned Samurai, Kyōsai was always able to appreciate the funnier side of life. From the age of six he was trained as a painter in the ukiyo-e tradition and his earliest works are accomplished examples of that genre. From 1857, however, when he dropped his given name of Shuzaburo in favour of the agnomen Seisei Kyōsai, meaning literally 'enlightenment crazy studio', his true calling was revealed. Setting the 'tone' for the kyōga so relished by his friend Robun, one of Kyōsai's earliest mature works depicts an old man whose testicles have become entangled in the strings of a young boy's toy. The old man contorts himself in agony, the little boy grins and the level of Kyōsai's humour is immediately apparent. By the time of his outrageous Fart Battle of 1867 and its companion piece the self-explanatory Phallic Contest, his wit had ripened to an all-time low. In the former, two teams spray each other with vividly-depicted noxious fumes as the courtesans, for whose entertainment the spectacle has been devised, swoon under the dreadful stench. But there is more to Kyōsai than mere bawdiness.

The 'demon paintings' of the 1870s, with which the painter made his name, are inspired fantasies of impish excess whose Tolkein-esque monsters cavort in the fantastic landscapes of the artist's psyche. Often they ape human activity. In Shojo Drinking Sake, little, hairy mythical creatures mirror the artist's favorite pastime, while in the Bosch-like School for Spooks of 1874 the demons are instructed in ways of tormenting their human prey.

In this latter work, which also parodies the Japanese adoption of Western teaching methods, Kyōsai hints at the more serious, satirical aspect of his art. However, it is as the painter of such comic tours de force as Cat on a Flying Fish, Frolicking Animals and the Battle of the Badgersand the Rabbits that Kyosai enters western popular consciousness alongside such icon-makers as Disney, Arthur Rackham and E H Shepherd. Although, as far as we know, they did it without the sake.

Kyoto National Museum: "Commemorating the 120th Memorial of Kawanabe Kyosai,Bridge to Modernity: Kyosai's Adventures in Painting" (April 8 - May 11, 2008)

Thursday, April 24, 2008One hell of a time: Meji Period 'Demon of Painting' looked West

What wasn't to like about an artist who painted the scroll "Hard Times in Hell," in which the king of Hell and his coterie of demons ascend to paradise in search of more suitable employment?

Laughter from official quarters was decidedly muted when the same acute satirical eye focused on contemporary society and its fondness for all things Western. Whether Kawanabe Kyōsai(1831-1889) really did depict an act of sodomy between foreigners and Japanese at a shogakai (a drinking and painting party) in 1870 is unsubstantiated. The jail time Kyōsai spent in the event's aftermath, however, is historical record.

Kyōsai's distinct sarcasm, playful virtuosity and extraordinary inventiveness are the themes of Kyoto National Museum's spring exhibition, "Bridge to Modernity: Kyosai's Adventures in Painting," showing till May 11.The artist lived in a time of extraordinary nationaland cultural tumult as Japan transformed itself from a feudalist society into a modern nation state. While his contemporaries were searching for methods to modernize Japanese-style painting — later given the name nihonga — or adopting more vanguard expressions in oil paint and imported Western styles, Kyōsai was a bastion of tradition.

Precious little about Kyōsai, however, is conventional. His apprenticeship as an artist began at the age of 7 in the studio of ukiyo-e(genre painting) artist Utagawa Kuniyoshi. Kyōsai had penchant for sketching from "life" that is illustrated by a macabre, apocryphal tale of the precocious student fishing a severed head out of a river — when he was 8 years old — to use as a subject for sketching practice.

From his 11th year through to his late teens, he was enrolled in the Surugadai branch of the revered Kanō School. The surplus of skill he exhibited earned him the nickname the "Demon of Painting" from Maemura Towa, his first Kanō teacher, which the artist later amended to "Intoxicated Demon of Painting" to convey his fondness for alcohol.

Kyōsai graduated from his Kanō training when still a teen, and the exhibition starts with a work from that time, "Bishomonten" (1848). While he revered the Kanō school, his allegiance to its principals slackened as he later took on other styles. The most significant deviation was a comic, vulgar style, often satirical and certainly eccentric.

An early precedent for the genre is seen in the "Scrolls of Frolicking Animals," attributed to Toba Sojo (1053-1140), a Buddhist priest. Kyōsai updated the style to notable effect, particularly in his "Fart Battle" (1867). Also shown in the Mori Art Museum's "Smile" exhibition last year, the scroll depicts participants being fed from a caldron of root vegetables to provoke a battle of gas as entertainment for palace courtiers. As the amusements progress, the passing of wind intensifies to the wind-powered launching of hay bales as missiles between the opposing teams. Spectators will note the essential qualities of manga here, which a concurrent event at the Kyoto International Manga Museum also showing till May 11, "Kyosai Manga Festa," makes even more explicit.

In larger paintings, Kyōsai depicted ferocious creatures of lore and legend. In "Ghost" (1883) he uses kaki-byoso (painted borders) in place of the conventional silk borders of the picture mounting, making it appear as if the ghost were rising free from the painted surface by appearing to extend beyond the customary painting space. In an even larger, 17-meter work, a curtain made for the Shintomi Theater called "Actors as the One Hundred Demons" (1880), Kyosai combined portraits of actors working at the theater with another of his favored themes, the "Night Procession of the Demons." Fortified with a few bottles of rice wine, Kyōsai completed the work in four hours. The result was a sensation.

With all this, it is remarkable to note — as Kanō Hiroyuki, the exhibition's supervisory curator, does in his catalog essay — that Kyōsai is generally unknown in Japan. Despite a memorial museum dedicated to the artist in Warabi, Saitama Prefecture, the present exhibition is the first large scale retrospective in this country of the his work.

A more persistent interest in Kyōsai has been taken up in the West, and the reason for this in part was Kyōsai's interactions with foreigners in the early years of the Meiji Period (1868-1912). In particular, Englishman Josaiah Condor was a student and intimate of the artist, and the one who held Kyōsai's hand on his deathbed. Early publications in English, such as Condor's "Paintings and Studies by Kawanabe Kyosai" (1911), which concentrated on the author's personal collection, spurred the affection.

Hopefully, Kyōsai's slippage into oblivion will be halted by this exhibition, and the free-spirited artist will be remembered as the "Intoxicated Demon" rather than another, late signature he used: "Nyoku (Like Emptiness)."

last revision: