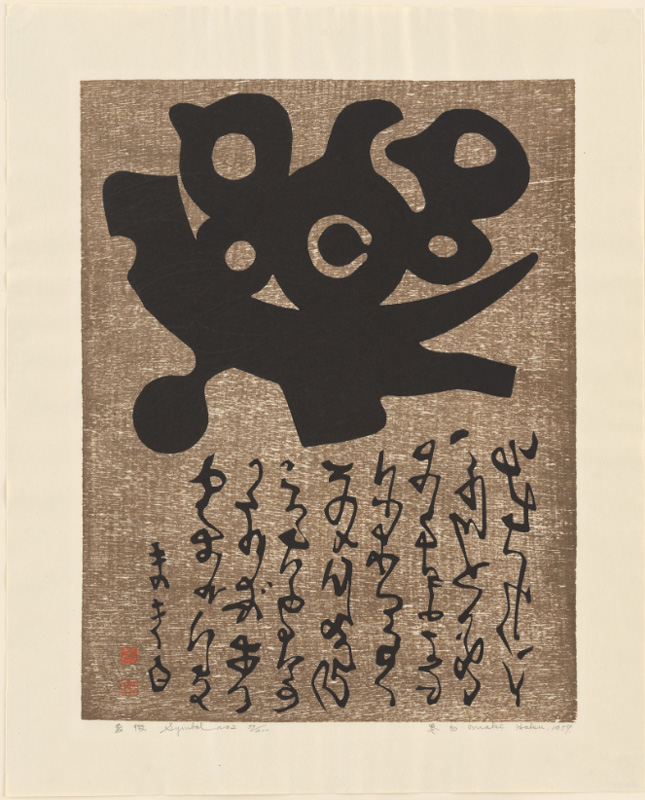

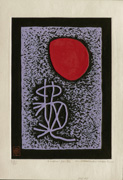

Symbol No 2, 1957

IHL Cat. #2050

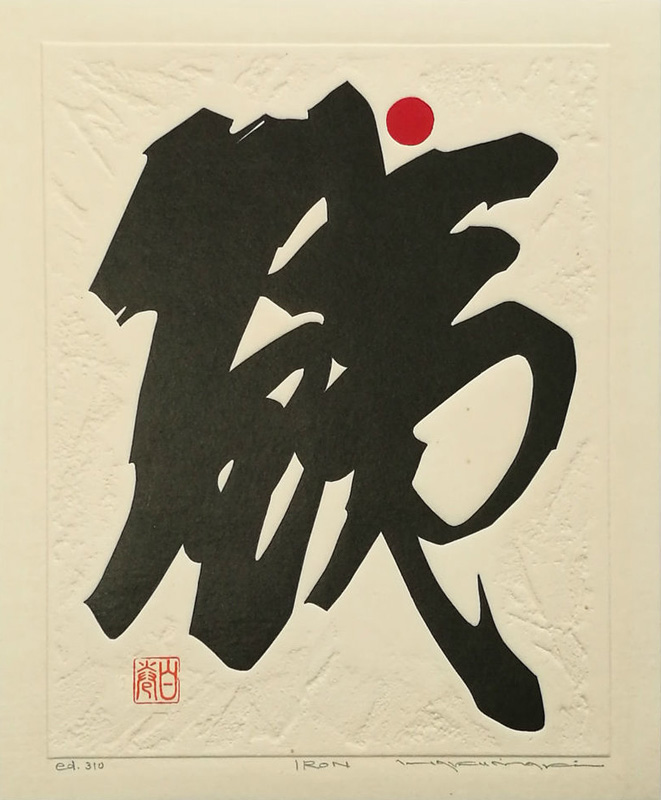

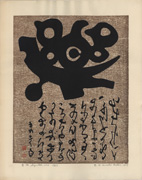

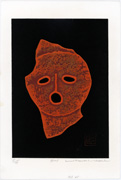

Ox, 1962

IHL Cat. #1336h

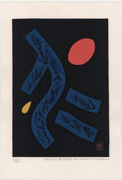

71-1, 1971

IHL Cat. #1717

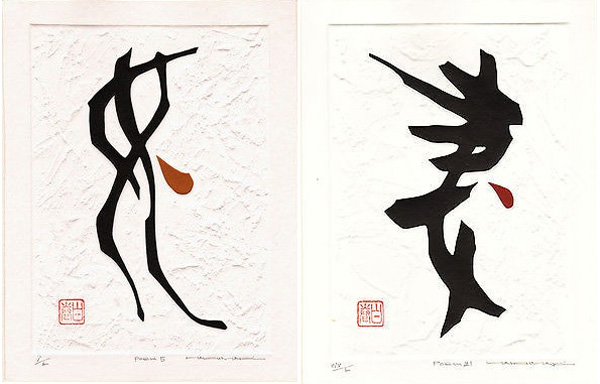

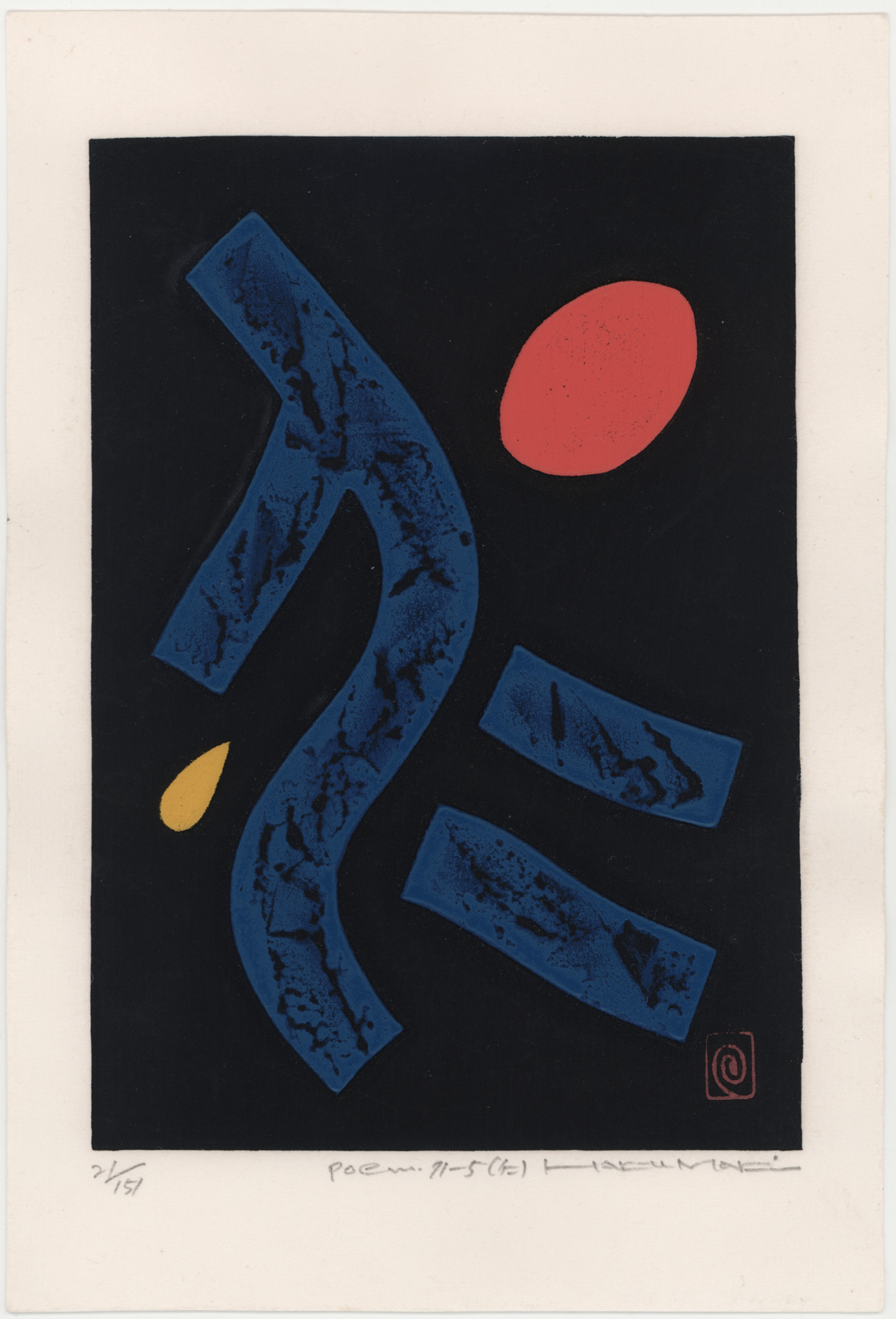

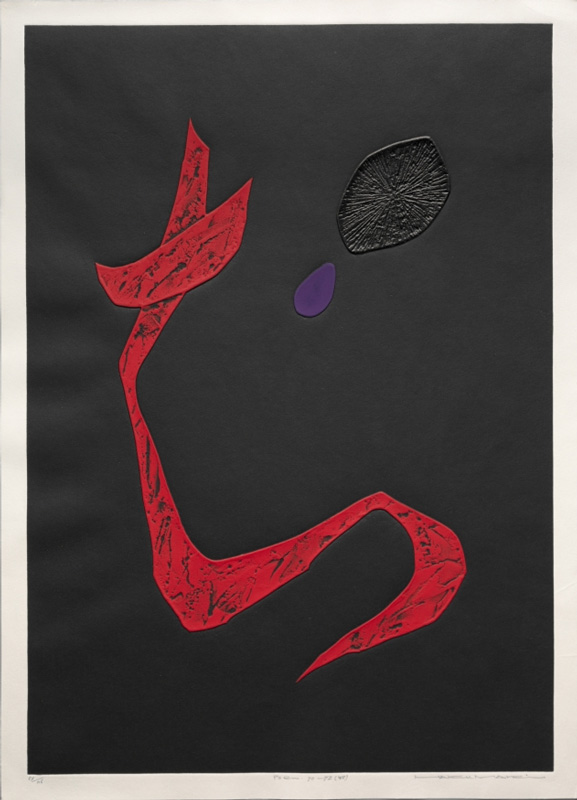

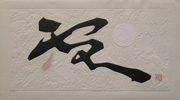

Poem 71-5 (仁), 1971

IHL Cat. #1718

Poem 72-3, 1972

IHL Cat. #2516

Poem 73-112 (Snow), 1973

IHL Cat. #2048

IHL Cat. #2275

IHL Cat. #1982

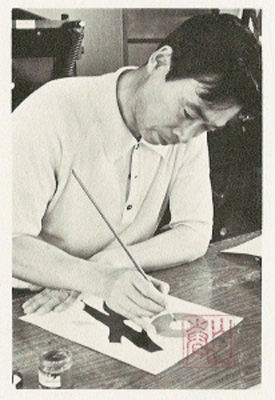

Profile

photo, mid-1990s CWAJ 1997 Print Catalog | Most of Maki Haku’s prints are immediately recognizable by their subject matter – often stylized kanji characters, ceramic vessels or fruit – and their deeply embossed images and velvety colors. During his almost fifty year career, Maki created approximately 2000 different print designs, with an average edition of 100 prints. His work was, and still is, extremely popular with collectors world-wide and is held by major museums around the world. | Tortoise 亀, 1977 |

Biography

Maki was born in the small town of Asomachi in Ibaraki Prefecture, about 80km northeast of Tokyo, on September 27, 1924 with the birth name of Maejima Tadaaki. His father likely died before he was born and he was raised by his mother. Towards the end of WWII he was trained as a kamikaze pilot, but was saved by the war’s end. After the war he graduated from Ibaraki Teachers' College in 1945 and became vice-principal of an elementary school there. In 1954 he married Takako Umeno. They would remain married throughout his life and were childless. Takako assisted her husband throughout his printmaking career along with her sister, who assisted in the printing process until sometime in the 1980s when Maki began hiring local assistants.

c. 1960s | While Maki had no formal art training, according to Petit he first started oil painting as a child and made his first prints as New Year’s cards, a popular custom of the time. What training he did receive was from two years of study with the pioneering sōsaku-hanga artist Onchi Kōshirō (1891-1955) attending meetings of the Modern Print Study Society (Gendai Hanga Kenkyūkai 現代版画研究会), founded in 1950 by Onchi and Kitaoka Fumio (1918-2007) under the auspices of the Nippon Hanga Kyōkai.1 He also may have participated in the last of Onchi’s First Thursday Society (Ichimokukai), meetings. In the late 1950s, he selected the art name (gō) Haku Maki (literally, “white roll,” with connotations similar to “airhead”) to promote himself as an eccentric artist who lacked academic training.2 According to Tretiak “Maki had few friends among the Japanese modern art community,” quoting his wife and his niece as saying “he had no close relationships with his contemporaries.”3 |

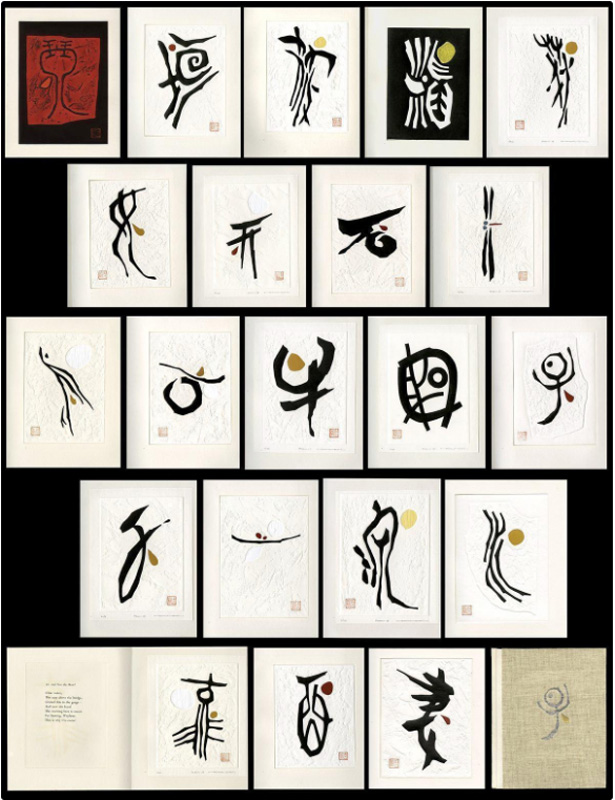

Maki first started making single-sheet prints, initially woodblock prints, in the mid-to-late 1950s and continued almost up until his death in 2000. Maki’s wife remembers his most prolific years as the twenty year period from 1964 to 1984, although sometime in the 1970s he developed pain in his arms, hands and shoulders that impeded his work, leading him in the mid-1970s to favor printing from carved woodblocks, a printmaking method he used early on in his career, rather than more arduous printing required using his blocks of molded/carved cement over wood. In 1975, again likely in response to physical limitations, Maki started working on a group of small (with images as small as 2” x 2”) woodblock prints which were issued into the 1980s in eight sets of twelve prints each with the overall title of San Mon Ban.4 The prints included in volume 1, issued in 1975 in an edition of 365, are shown below along with the cloth covered box containing the prints, each of which was tipped to an 8 x 8 inch mat board. His wife Takako remembers that “San Mon Ban was created using as models certain large prints he liked and [he] made them into smaller prints for San Mon Ban or used San Mon Ban creations to make larger prints later.”5

An early Maki woodblock print Symbol 2, 1957 16 1/8 × 12 3/8 in. (40.9 × 31.5 cm) sheet: 19 11/16 × 16 1/16" in. (50 × 40.8 cm) woodcut Museum of Modern Art, 64.1959 | San Mon Ban (portfolios of small prints) Volume 1, 1975 each image 2 x 2 in. (5.1 x 5.1 cm) |

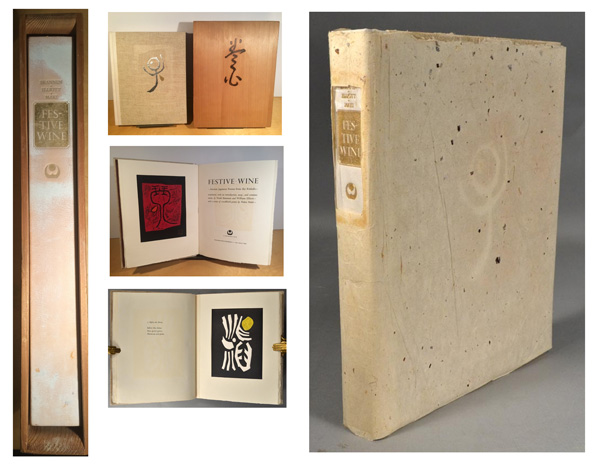

In 1962 his woodblock print Ox (see this collection’s print IHL Cat. #1336h) was one of ten prints chosen for James Michener’s seminal work and portfolio of prints The Modern Japanese Print: An Appreciation. This book along with the 1969 award-winning (receiving the Mainichi International Publishing Culture award) book Festive Wine, a translation of twenty-one 5th to 9thcentury poems, each accompanied by a Maki print, popularized his work internationally and increased the audience for his prints.

Festive Wine: Ancient Japanese Poems from the Kinkafu

The works he is best known for are his prints of kanji characters drawn in calligraphic form, sometimes producing characters that bear minimal resemblance to the actual character. In commenting on Maki’s style, one of the authors of Festive Wine wrote:

Maki himself referred to the style he based his hanga on as shōkei moji which is the Japanese translation of hieroglyphics. What he meant by this was that he took kanji in their current shape and used his imagination to create what he thought may have been the original pictograph behind them. This is especially evident in his renderings of the character for Woman 女 (Poem 5) and Wife 妻 (Poem 21) [both shown below], where he imbues them with feminine grace and suppleness.6

Donald Jenkins in Images of a Changing World: Japanese Prints of the Twentieth Century tells us that Maki was “Not a calligrapher in the strict sense of the word, Maki is a student of ancient Chinese ideograms and characters. He derives ideas for prints from them, although he may alter the characters to enhance the overall design.“7

Maki himself in discussing his print Ox states: “I have here tried to give our cultural heritage of such ideographs a modern feel, but in an Oriental style. This means trying to capture the typically Japanese expression of the beauty of space, the sense of reverence for and persistent pursuit of boundless space, while at the same time taking advantage of the boundary provided by the beauty and life of the paper itself.”8

This kanji is easier to read than most of the stylized characters appearing in Maki's prints. Like many of his calligraphic kanji, it looks like the "seal script" form of this character. Maki has also used the character in the print's title, something rather rare to find in one of his print titles.

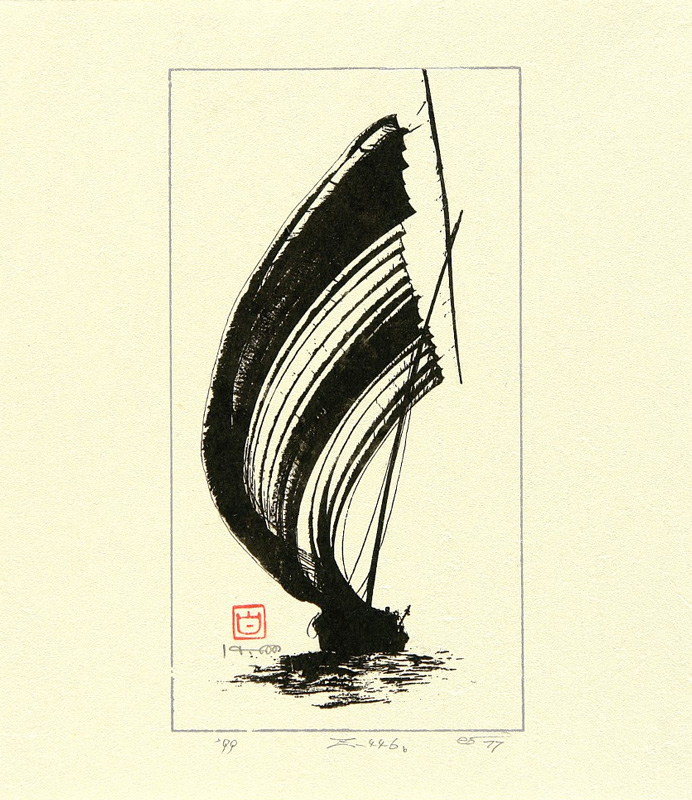

Beyond these “kanji” prints, Maki chose pottery (particularly, ceramic vessels such as tokkuri, sake cups, tea bowls), ancient clay funerary figures and fruit (particularly pomegranates) as favorite subjects for many of his prints. Large numbers of his prints also carry the title “Poem” followed by a number, perhaps in homage to his mentor Onchi many of whose prints carry the title poem or were inspired by poetry. Late in his career Maki also produced prints depicting multi-color go boards and some geometric pattern works and a small number of prints depicting Mount Fuji. His last known prints were simple woodblocks of traditional sail boats.

While Maki created some prints from woodbocks, both early and late in his career, the bulk of his works were created from his unique combinations of woodblock, cement and sometimes cardboard as a printing block. These amalgamations consisted of a base of plywood, or sometimes cardboard, covered with a mixture of Portland cement, water and a bonding agent, which he molded and carved to create images and backgrounds. The resulting prints show deep embossing of images and, on some prints, a deeply embossed pattern as background. It is a different look than what can be achieved through woodblock printing. On occasion, he will cut shapes from heavy cardboard and glue them to the woodblock, creating a collage of forms.

Several authors have offered slightly varying descriptions of Maki’s printmaking process. The below brief description is drawn from Gaston Petit’s detailed description in Evolving Techniques in Japanese Woodblock Prints.

In the early 1960s Maki developed his own process of relief printmaking using woodblocks and cement. He first carved a conventional woodblock and then placed a cement mixture around the areas raised in relief onthe block. Before the cement was set, Maki would texture it and after it dried he carved and chiseled the cement into the desired shape. After the cement completely dried, the entire surface of the plate was shellacked.

He would then roll his colors, which could include poster paints, oil paints and offset printing inks, onto the relief areas of the block, using stencils to define the areas to be inked. He often applied a film of red oil paint or cobalt blue slightly diluted with turpentine over his colors, which added a deep velvety appearance to the final print.

Paper is placed on the inked block and is first hand-rolled with a soft roller to adhere it to the printing block and then passed through an etching press, where heavy pressure was applied to emboss the paper and print the images. He then would take a second piece of paper covered with diluted rice paste and hand bond it to the printed paper using a hand-roller. He followed this with two additional passes of the bonded papers through the etching press, laminating the two sheets and creating even deeper embossing on the paper. On three sheets of paper would be laminated together.

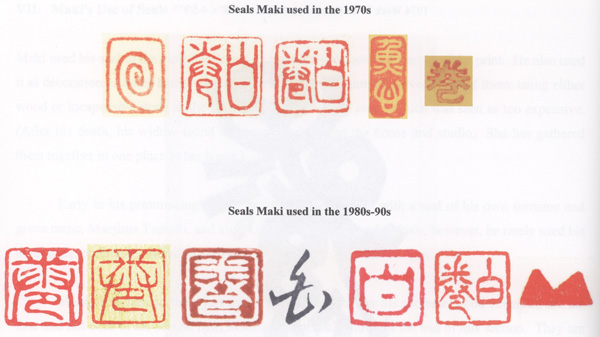

Occasionally, he would hand-apply color to specific areas of the print. As a last step, Maki added his artist seal. which he viewed as part of the composition.

Tretiak quotes a number of Maki acquaintances, all of whom saw Maki as modest, kind and gentle. Lawrence Smith describes him as “A man of very independent spirit” who “remained devoted to large editions at low prices available to ordinary people…” even as his fame grew.9

In 1998, Maki underwent surgery for stomach cancer, which was to take his life in 2000. He worked, with the assistance of his wife, almost until his death.

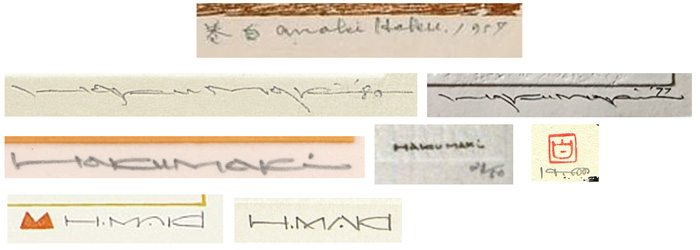

Signatures and Seals

Maki used a number of seals, many of which he carved himself. Tretiak reports that early on in his career he used a seal with his given name, Maejima Tadaaki, as well as his artist’s name, but gave that up by the early 1960s. Maki, as did many Japanese artists, considered his seal part of the design.

Organizations, Galleries and Museums

During his career Maki’s work was shown in at least fifteen galleries in Japan, including the well-known Red Lantern and Yoseido Galleries in Tokyo. Starting in 1957 he consistently participated in the Japanese Print Association (Nihon Hanga Kyōkai) Exhibition), an organization which he became a member of in 1958, and in the College Women's Association of Japan (CWAJ) annual print show starting in 1960. He also participated in international shows wining several prizes and representing Japan in the 1967 Venice Biennale.10

In 1991 he and his wife visited San Francisco for a gallery exhibition and followed that with a visit to Yosemite National Park. Maki visited the US again in 1995 and 1996 for shows in a Seattle gallery.

Maki’s work is held by museums world-wide including the British Museum; Art Gallery of Greater Victoria; Museum of Modern Art, New York; Brooklyn Museum; The Philadelphia Museum; Honolulu Museum of Art; Art Institute of Chicago; Cleveland Museum of Art; Hood Museum of Art, Dartmouth College; Harvard Art Museums; Museum of FineArt, Boston; Los Angeles County Museum of Art; Portland Art Museum, Portland Oregon; Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco; Tikotin Museum of Japanese Art, Haifa.

Online Resource

- Item Title:

- Haku Maki Catalog Raisonné database.

- Author(s):

- Craft, Robert ; Tretiak, Dan

- Imprint:

- http://haku-maki.com/

- Language:

- English

- Illustrations:

- numerous color ills.

- Concordance:

- No

- Bibliography:

- No

- Index:

- No

- Exhibition List:

- No

- Chronology:

- No

- Link to digital online content:

- https://n442.fmphost.com/fmi/webd#Maki%20Catalog

- Content Note:

- The database was revised and uploaded in 2018. It now contains over 1,400 records, and will be continually updated and supplemented.

Entries give catalogue number (based on date and number within year for the period 1960-1980, with modified dating patterns for other "named" print series), year, title, edition, keyword, dimensions in inches, original DT file label.

There is a search and find function allowing sorting by selected critera.

- Public Note:

- The online catalogue is a work in progress. Information is based on the research of Dan Tretiak (who published a first monograph on the artist in 2007) and his wife, Lois Tretiak.

This research was put up on the present website by Robert Craft.

last revision:

ihl2275 thumb web.jpg)