Prints in Collection

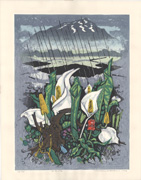

from the series The Face of Tokyo, 1949

IHL Cat. #642

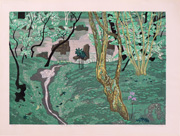

Shinjuku Garden

from the series The Face of Tokyo

IHL Cat. #2020

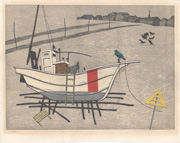

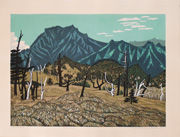

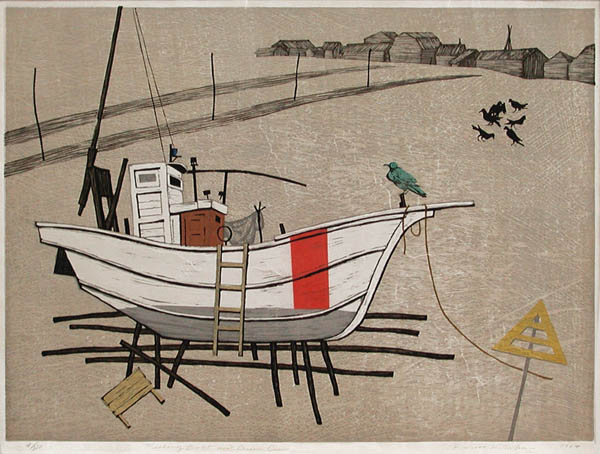

Fishing Village Fishing Village in the Afternoon, 1967 IHL Cat. #194 | IHL Cat. #1604 |

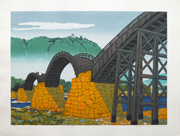

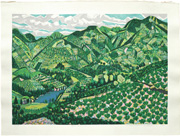

IHL Cat. #1412 | Kintai Bridge, 1979 IHL Cat. #1570 | Iyo Tangerine Mountain, 1981 IHL Cat. #1569 |

IHL Cat. #907

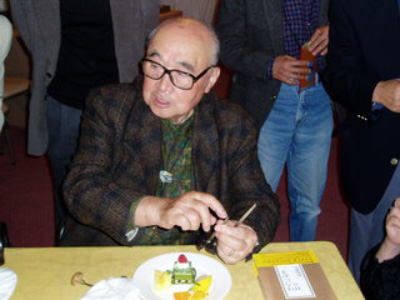

Biographical Data

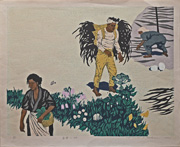

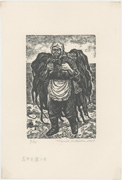

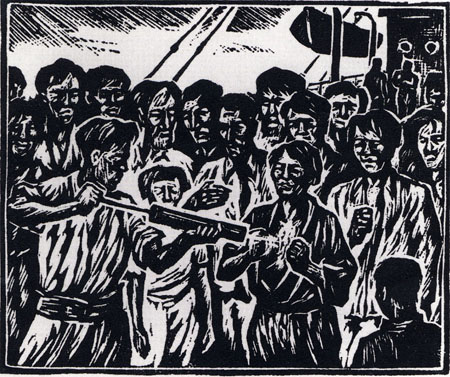

in Minneapolis. Kitaoka was a Fullbright visiting professor at the Minneapolis School of Art in 1964-65. | BiographyKitaoka Fumio 北岡文雄 (1918-2007)Sources: http://www.cartage.org.lb/en/themes/biographies/MainBiographies/k/Kitaoka/kitaoka.htm and Revisiting Modern Japanese Prints: Selected Works fromthe Richard F. Grott Family Collection, Helen M. Nagata, HelenMerritt, Northern Illinois University Art Museum, 2007, p. 93 and as footnoted. Fumio Kitaoka (Tokyo, born,1918) is one of Japan's finest woodcut masters of the latter twentieth century. He first studied printmaking techniques and drawing under Unichi Hiratsuka (1895-1997) at the Tokyo Bijutsu Gakko. Graduating during the Second World War, Kitaoka first taught art in Tokyo and in January 1945 was posted to a similar position in occupied Manchuria. His experiences in China led to the social realist series of 17 prints Journey to the Native Country (1947) chronicling his difficult repatriation to Japan. DDT Before Disembarkation (joriku mae no DDT) 1947 From the series Journey to Native Country (Sokoku e no tabi) 10.3 x 13.1cm "Journey to Native Country exposes the complete chaos caused by the collapse of Japanese colonial rule... [T]he artist finally arrives on Japanese soil but is subjected to a dehumanizing fumigation, as a DDT sprayer is fired directly onto his chest."1 |

Upon returning to Japan

In the mid-60s, Kitaoka taught at the Minneapolis School of Art and at Pratt Graphic Arts Center in New York.

For years, the woodcut art of Fumio Kitaoka has been the subject of many exhibitions in Japan, America and Europe. Museums that list his woodcuts within their permanent collections include, the Museum of Modern Art, New York, the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, The Art Institute of Chicago, the National Museum, Warsaw and the Japanese Museum of Israel. Fumio Kitaoka has been named an honorary member of the Japan Print association and has served as Director of the Japanese Artists Association.

He died of pneumonia on April 23 2007.

1 Made in Japan - The PostwarCreative Print Movement, Alicia Volk, Milwaukee Art Museum, 2005, p. 33-34.

I had thought that Kitaoka both carved and printed all his work, but recently I came across the book Contemporary Japanese Prints I: A Comprehensive Catalog (Vol 1), Kodansha International, 1983 containing three of Kitaoka's prints dated 1982 which are noted as printed by Tetsui Takayuki (b. 1936).

A Dream of Realism

Source: Orientations Asian Art Magazine Volume 38 Number 7 October 2007According to Kiyoko Sawatari, Chief Curator of the Yokohama Art Museum, Kitaoka's dream was to "revive realism in woodblock prints". Throughout his 60 years of printmaking, he “proudly traveled his own road”, leaving a legacy of works “which are the expression of the heart and soul of a devoted man”.

To quote Helen Merritt: "After passing through realistic and abstract stages, Kitaoka's mature style embraces both realistic representation and abstraction in carefully designed and often brightly colored landscapes".

Interview with the Artist

Source: Evolving Techniques in Japanese Woodblock Prints by Gaston Petit and Amadio Arboleda pub. by Kodansha International Ltd.,1977,p. 113–117.

Question: Do you have a theme or idea in mind before you start a print?

Answer: I start a print only when the theme and idea have grown clear and definite in my mind. Printmaking, because of its very nature, requires that the whole process should be precisely worked out beforehand.

Question: What is it you generally wish to express in your work?

Answer: Decayed rafts, fishing villages, rocky seasides. Whatever subjects I choose, I want to express through them the profundity of nature and the feeling of eternity. This attitude may appear too seclusive [sic] or ignorant of our actual community, yet I believe in the end that it relates to a love of mankind.

Question: What do you want your work to communicate to the viewer?

Answer: What I have stated before, a feeling of eternity. At the same time, I am interested in the viewer’s response to my technique.

Question: What aspects of the ukiyo-e tradition do you feel have value for you?

Answer: It is true that we have adopted the tools and materials of ukiyo-e, as they have been handed down to us in their finished state. As for the technique or expression, we owe practically nothing to the ukiyo-e artists, since modern printmaking started as a negation of this tradition. The techniques used by the ukiyo-e artists are still worthy of study though, for one might yet find methods that can be utilized in the making of modern prints.

Question: Does any aspect of politics or religion enter into your art?

Answer: My works are not related in any way to politics or religion. Yet, as I stated before, I stand in awe of nature and often feel an impulse to plunge into it. This feeling, in the sense that it seeks harmony between man and nature, might be called religious.

Question: Because artists are much more international, know what is being done everywhere in the world and have access to reproductions and original works of art, it is often difficult if not impossible, to relate a work of contemporary art to the nationality of the artist. In the light of this statement, do you feel you are expressing something that has a particular Japanese significance – aside from the fact that you are Japanese working in Japan – or are you more concerned with a universal or international point of view or style?

Answer: I once believed in the international style or in that way of thinking because I felt more or less obliged to do so. At present, though, I feel that I should express something Japanese, or more precisely something representing myself – who happens to be Japanese. This, however, does not mean selecting such subjects as Japanese gardens or Buddhist icons – the accomplishments of Japanese art of the past – for this appeals only to foreigners in their search of the exotica of the Orient. I feel that I should derive my creative activity from the deeper thoughts of the Orient, from a feeling that has its roots in Japanese nature and the Japanese way of living.

Question: What are your thoughts concerning content, - that is, the idea, story, theme and message, and form – plastic values, design, structure, spatial relationships and so forth? Content and form cannot be completely separated, of course; but which of the areas do you value most? How do you consciously relate the areas of content and form?

Answer: Form is meaningless without content, so I consider content more important. However, it is true that content itself cannot make a work of art unless it has an appropriate form. Form may take precedence over content in the immature state of a work of art, but in a consummate work, form and content are absolutely inseparable and should blend together in a perfect unity. Though I have a clear vision of content, I always have to suffer in search of the proper technical solution for its ideal form, encompassing the plastic values, design, structure and spatial relationships.

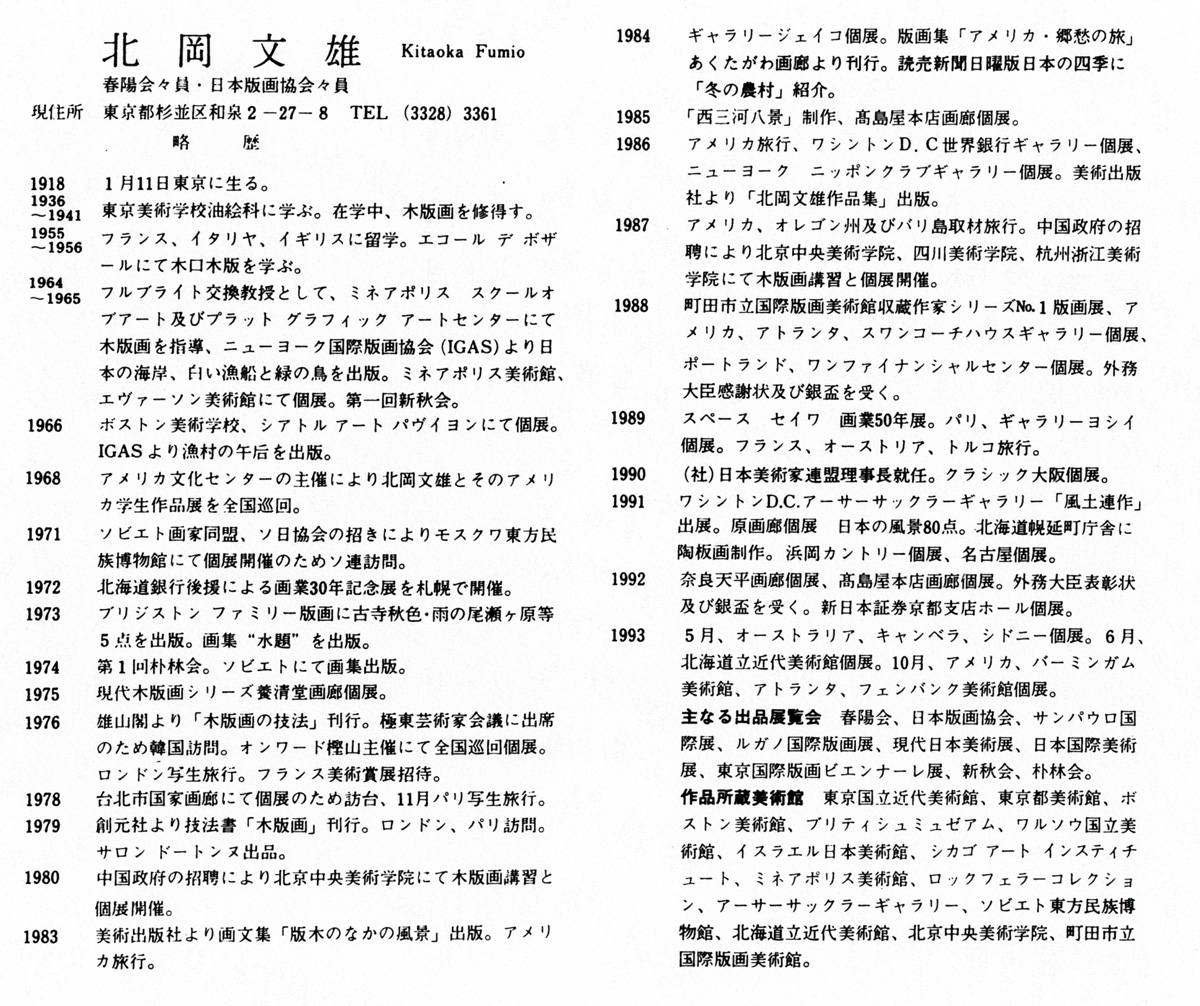

The below timeline was included with several of the artist's prints in this collection