Haniwa (4), c. mid-late 1950s

IHL Cat. #1922

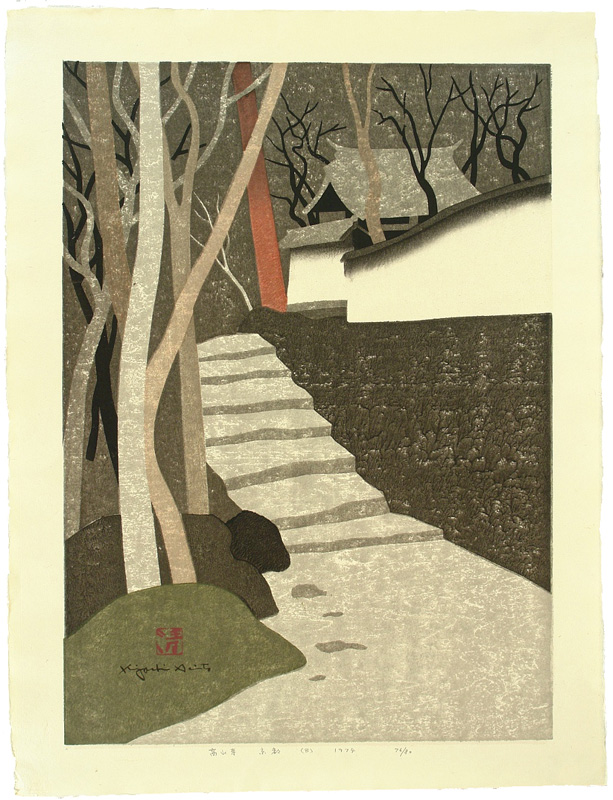

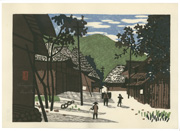

Village of Mito, c. 1959

IHL Cat. #1648

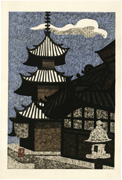

Pagoda, c. 1960-1980

IHL Cat. #1910

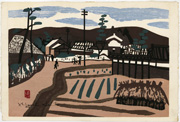

Plowing the Rice Field (The Seasons: Spring), c. 1960-1970

IHL Cat. #984

Summer in Aizu (The Seasons: Summer), c. 1960-1970)

IHL Cat. #636

Bunraku samurai, undated

IHL Cat. #1514

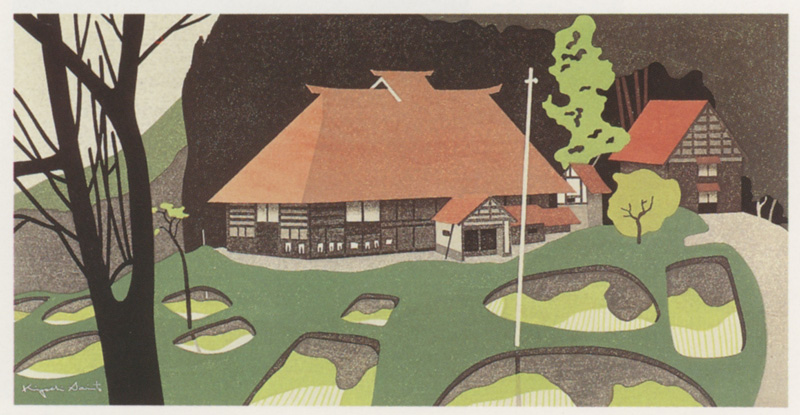

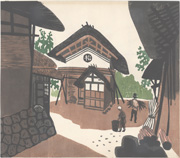

Village Storehouse, undated (c. 1959?)

IHL Cat. #2380

Biographical Data

Profile

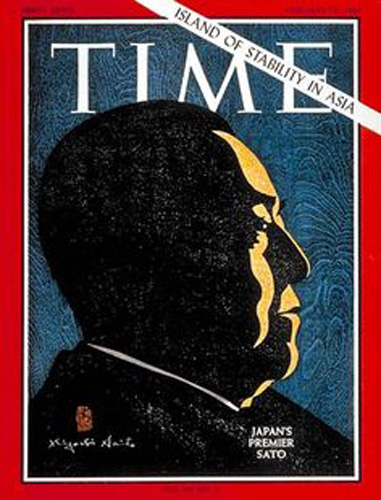

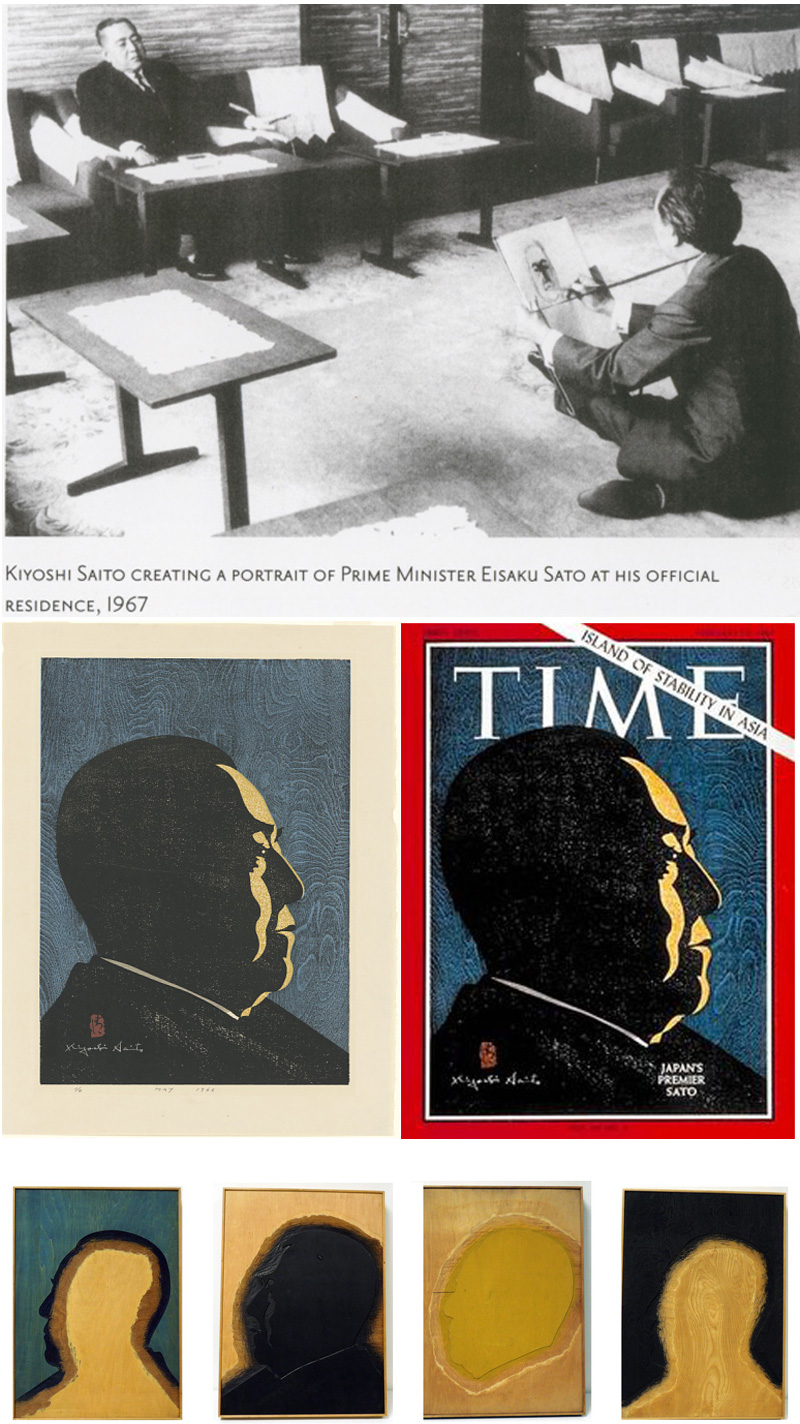

| Aseminal figure in the resurgence of the Japanese woodblock print after WorldWar II, Saitō was a mostly self-taught artist who first worked in oils and thendedicated himself to woodblock prints. With his winning of a special prize for Japanese artists at the FirstBiennial Exhibition of the Modern Art Museum of Sao Paolo in 1951 he waslaunched onto the world stage. He becamea favorite of American collectors and in 1967 his woodblock print of then PrimeMinister Eisaku Sato appeared on the cover of Time Magazine. His woodblock prints are known for theirprominent display of woodgrain, simple forms, and wide variety of subjects, allof which are uniquely Japanese. Whilehis subject matter is Japanese, the artist credits Gaugin, Munch, Redon, Mondrianand other Western artists as important influences on his work. Honored as bunka kōrōsha (Person of CulturalMerit) in 1995, Kiyoshi passed away at the age of 90 in November 1997, shortlyafter opening the Kiyoshi Saitō Museum of Art in Yanaizu.

|

Biography

Sources: 44 Modern Japanese Print Artists, Gaston Petit,Kodansha International Ltd., 1973; Modern Japanese Prints: An ArtReborn, Oliver Statler,Charles E. Tuttle Company, 1956; Modern Japanese Woodblock Prints -The Early Years, Helen Merritt, University of Hawaii Press, 1998;Masterful Images: The Art of Kiyoshi Saito, Barry Till, Pomegranate Communications, 2013 and asfootnoted.

Early Childhood

Born in the small village of Aizubange, Kawanuma inFukushima prefecture on April 27, 1907, Saitō knew poverty as a child. He was four or five when his father lost hisbusiness and moved the family to Yubari, Hokkaido where he found work in the Otarucoal mines. His mother died when he wasthirteen and he was sent off to be the ward of a Buddhist temple twelve hundredmiles from home. Unhappy at the temple he tried to buy a railway ticket home. A sympathetic priest interceded and sent him back to Yubari.

Moving to Tokyo

Displaying an aptitude for drawing, Saitō was taken on asan apprentice sign painter in Otaru and by the age of twenty set up hisown business designing signs for storefronts which provided him with a modestincome. In Otaru he studied drawing withNarita Gyokusen 成田玉泉 (1902-1980) and experimentedwith painting in oil (i.e. Western-style or yōgapainting.) “Determined to avoid thepoverty of his parents, he thought the only route open to him was that ofcommercial art. But he also dreamed ofbeing an oil painter”1 and in 1931-1932moved to Tokyo taking work as a sign painter and studying Western-stylepainting at the private Hongō Kaiga Kenkyūjo [Hongō Painting Institute, foundedin 1912 by Okada Saburōsuke (1869-1939) and Fujishima Takeji (1867-1943).] He was also drawn to Tokyo by the thought ofjoining Munakata Shikō’s (1903-1975) group of struggling young artists which he heard aboutthrough a local elementary school art teacher. While living in Otaru it is reported that he personally met Munakata,one of the towering figures in the sosakuhanga (creative print) movement.

Print Making

In Tokyo, his oil paintings were exhibited under theauspices of a number of societies including Hakujitsukai (Midday Society),Nikakai (Second Division Society, in which Yasui Sōtarō participated), Kokugakai (National Picture Association) and Tokōkai (EasternLight Society). However, his paintings didnot receive the acclaim he hoped for, leading him to experiment with woodblockprintmaking, at first using a single block which he carved himself and printedprogressively, a self-taught skill. In describing Saitō’s prints during thisinitial phase of printing, curator Barry Till notes “…his methods were quiteunusual. He started out making only oncecopy of each work but soon realized that he could produce many copies.” Petit relates that while at the Hongō PaintingInstitute he discovered that “the woodblock prints he had been experimenting with werea well-established form which could be produced in editions and could use morethan one block.”3

Crediting the “clear vivid colors” in the woodblock printsof Western-style painter Yasui Sōtarō (1888–1955),Saitō began seriously producing his own prints in 1936 at the age 29. It was not long before his prints wereaccepted for showing at the 1936 5th annual exhibition of the prestigious Nihon Hanga Kyōkai (Japan PrintAssociation). While print makingsupplanted painting as Saitō’s main oeuvre, he maintained a somewhat ambivalentattitude towards the physical creation of a print, telling Statler in 1956 that“For me, the joy of making a print is not in working with the materials but increating the design” and “when I’m trying for a new or complicated effect Ihave to do the work myself even though I don’t especially enjoy it.”4 A similarsentiment was conveyed to Gaston Petit in 1973 who writes “[Saitō] felt nourgent compulsion to make prints; he simply wanted to create a work of art.”5

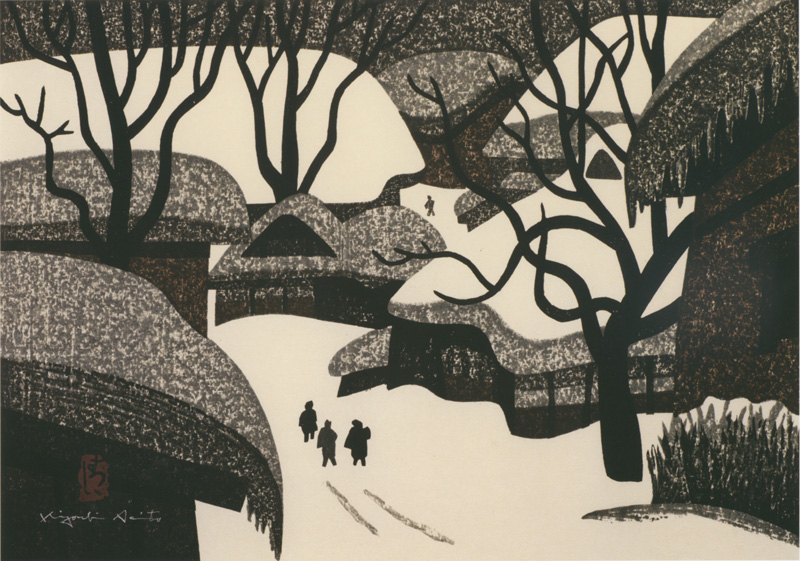

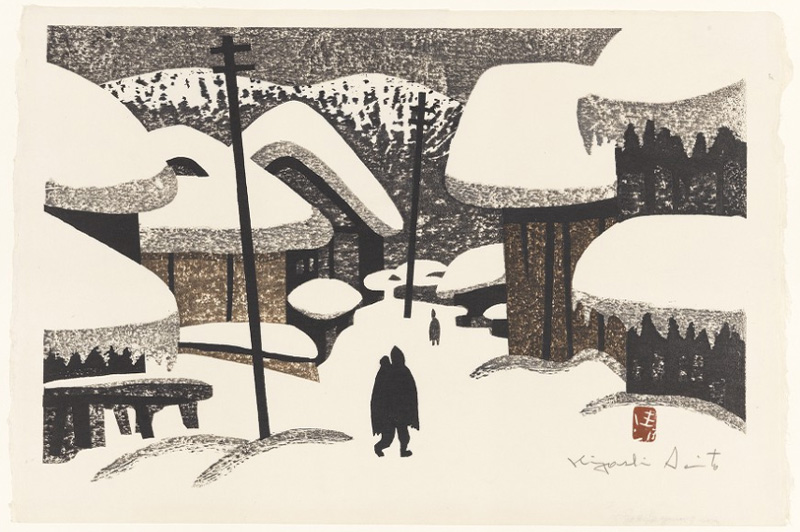

Winter in Aizu (会津の冬)

In 1937 the print division of the Kokugakai accepted one ofhis prints (along with one of his oil paintings) for showing at their 12thexhibition, but in 1938 he was stung by the Kokugakai’s rejection of his printsand paintings. Returning to Aizu in 1938he began his print series Winter in Aizu depictinghis childhood village until the age of four or five. These early prints began to establish his unique,easily recognizable style and were the basis for his first solo show in 1942 atthe Kyūkyodō brush shop gallery in Ginza. Saitō would continue to make prints depicting winter scenes in Aizu eithertitled Winter in Aizu or untitled throughouthis career and there are over 100 prints that carry that title or depict Aizuunder a blanket of snow.6 Some of these prints were made in numberededitions and some were made in open editions.

In speaking about these first prints Oliver Statler relates:

These were important prints, but it took them a long time to assert themselves. The war intervened; he washed the pigments out of his canvases so that his wife could make them into clothing, but he guarded the blocks for the Aizu prints. "No matter how rough things were," he says, "or how often we had to move to keep a roof over our heads, I held on to those blocks. I couldn't say why, but I did."7

Untitled [Winter in Aizu (B)], 195317 15/16 x 23 7/16 in. (44 x 59.5 cm)University of Michigan Museum of Art 1958/2.2

Winter in Aizu (5), 1958

15 x 20.7 in. (38 x 52.7 cm)

Winter in Aizu (13), 1969

Sheet: 14 9/16 x 20 /12 in. (37 x 52 cm)

Art Gallery of Greater Victoria 1969.102.001

Untitled, Winter in Aizu (3)

John J. Burns Library, Boston College MS.2013.043

In 1939 he joined Zōkei Hanga Kyōkai (Formative Print Society– also translated as Plastic Print Society) at the invitation of its founder, print maker Tadashige Ono (1909-1990). Tadashige’sgroup “imposed no standards to be met and offered Saitō the support group heneeded in order to develop in his own way.”8

Post-War

In 1944 Saitō took work at the Asahi Newspaper Company(most likely as an illustrator) where he was employed until 1954. It was while working at the Asahi in about1945 that he met Onchi Kōshirō (1891-1955), a foundingfather of the creative print (sosakuhanga) movement and the leading abstract print artist, who invited him to hisFirst Thursday Society (Ichimokukai) where many of the sosaku hanga artists regularly met. Onchi included Saitō’s print Ginzain his second issue of Ichimokushū, a collection of prints by Ichimokukai members, published in May 1946. Saitō’s associationwith Onchi, who was courted by Western print lovers, would help him gain entryto various post-war exhibitions targeted at Western audiences.

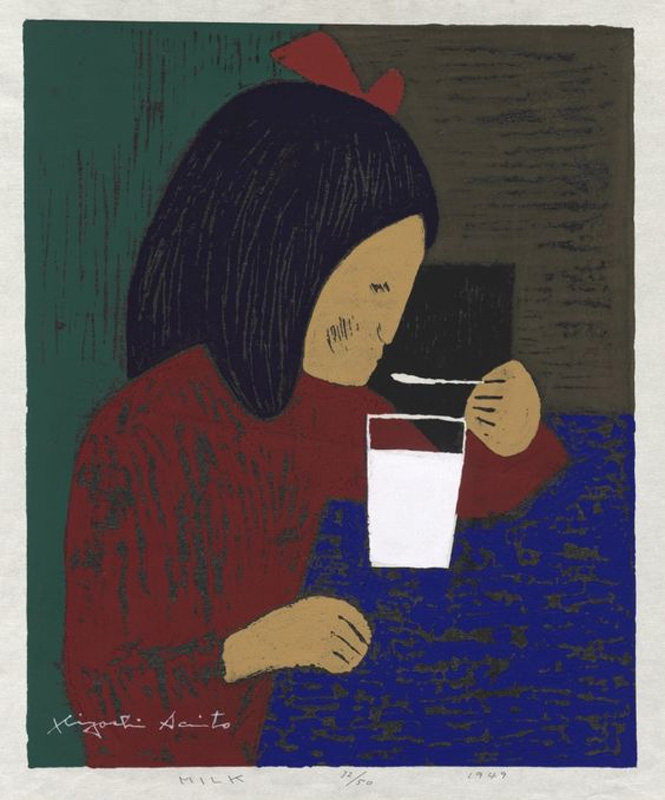

Milk, 1949 Image: 14 1/4 x 11 3/4 in. (36.3 x 29.84 cm) Cleveland Museum of Art 1985.497 | In the period following the end of the Pacific War artists struggled to get the supplies they needed, but with the Occupation and the influx of Americans fascinated with Japanese prints, print making began to revive. Americans were enchanted by images of “exotic” Japan and Saitō’s work was immediately appealing to them. He was invited to exhibit his work in 1945 or 1946 in a three-man show along with Hiratsuka Un'ichi (1895-1997) and Kawanishi Hide (1894-1965) in a new gallery near the Imperial Hotel where it was a hit with Americans, surprising the artist and leading to his first sales. By 1948 his Winter in Aizu prints were sought after and in 1949, at the age of 41, he received first prize for his print Milk at the Salon Printemps Exhibition which had been organized to support young Japanese artists with the backing of wives of senior GHQ officials.9 Saitō contributed to several multi-artist print series issued during the early years of the Occupation, the best known being Scenes of Last Tokyo (Tokyo kaiko zue), a portfolio of fifteen prints created by nine artists, all members of Nippon Hanga Kiyōkai (the Japan Print Association), and spearheaded by Onchi Kōshirō. Now an accomplished and recognized print maker, he became a member of the Nihon Hanga Kyōkai (Japan Print Association) in 1947 and the Kokugakai (National Picture Association) in 1950. |

TheBreakthrough

U. S. State Department. In 1957 he was awarded a prize at the 2nd Ljubljana Biennial Graphic Arts. In the late 1950s and through the 1960s, hetravelled to Paris, Europe, New York, Hawaii, Australia, India, Canada andother international destinations for various exhibitions. His travels would continue into his early 80s.

Front Page of Time Magazine

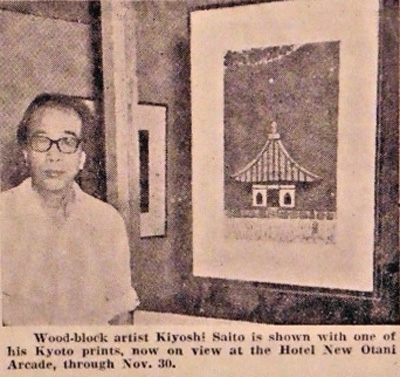

| While the Time magazine cover certainly increased his reputation abroad, a few months earlier The Japan Times noted in a review of his exhibition in the Hotel New Otani Arcade, "There are few Japanese artists living in Japan who are so widely known abroad as Kiyoshi Saito. He is also exceptional in that his name in Japan proper is not so readily recognized ..."14 Gradually this would change and his "popularity abroad was reimported into Japan...." 15 At the age of 74 he was honored with the Fourth Class Order of the Sacred Treasure by the Japanese government and in 1995 at the age of 88 he was honored as bunka kōrōsha (Person of Cultural Merit), an honor bestowed on men and women by the emperor who have made an outstanding contribution to the development and advance of science and culture. |

His Oeuvre

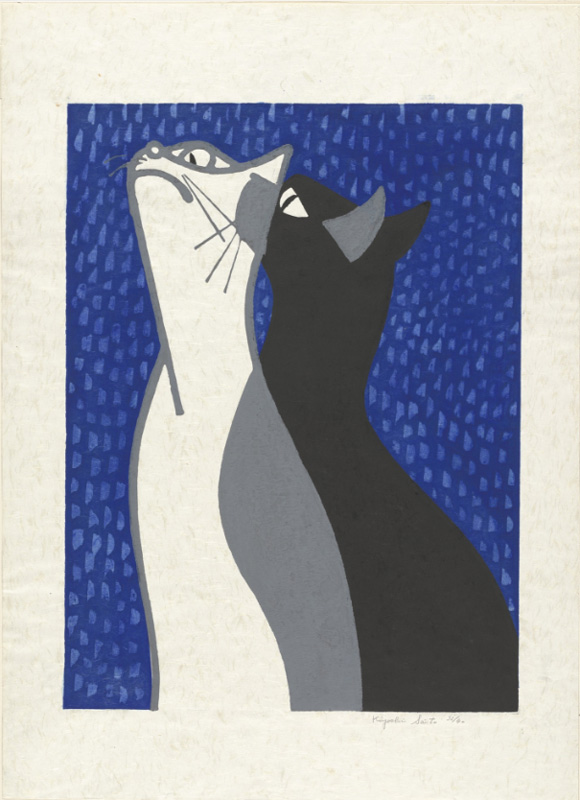

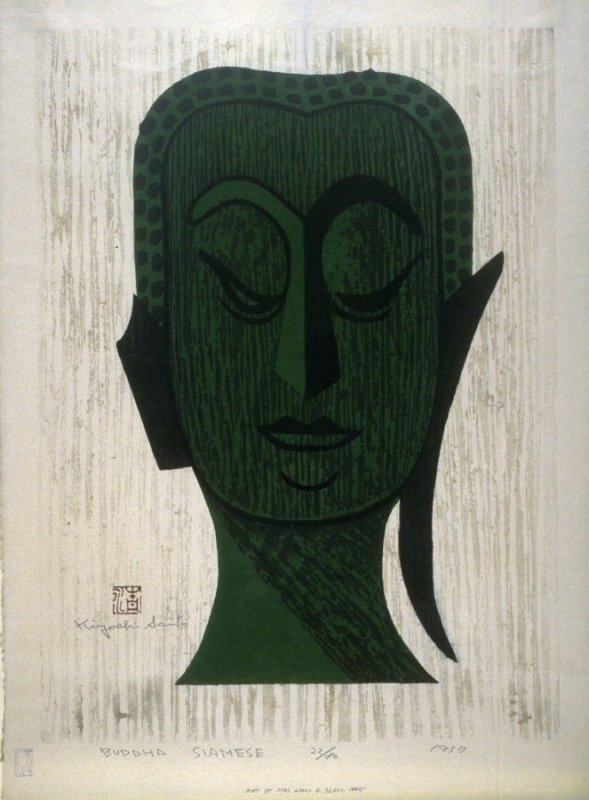

In an attempt to definethe first twenty years of Saitō’s prints, Statler tells us ““Saitō himselfdivides his work into three periods” - an early period dominated by the Aizusnow scenes, a period of realism beginning in 1945 typified by portraiture “andby 1950, a move toward simplification…”16 His later work merged modern elements ofmodernism, cubism, abstraction, and impressionism with Japanese tradition,after having been influenced by famous modern artists such as Piet Mondrian,Pablo Picasso, Henri Matisse, Wassily Kandinsky, Paul Gauguin, and EdvardMunch. His subject matter was diverse including Buddhist subjects, the buildings and culture of Kyoto, studies of ancient pottery (e.g., Haniwa burial figures), animals (particularly cats), flowers, bunraku, andlandscapes of the countryside, most often with several anonymous solitaryfigures going about their everyday business and an array of prints based on his overseas travels. Saitō's prints, with their flatareas of color and solid textures, were the result of his search for theessentials of nature.

Bunraku Puppet,

c. 1970-1980

sheet: 16 1/2 x 11 1/4 (42.2 x 28.7 cm)

Artelino 53293

In the words of author and print connoisseur James Michener, “Neverstatic, he has progressed through many styles, always with distinction.”17

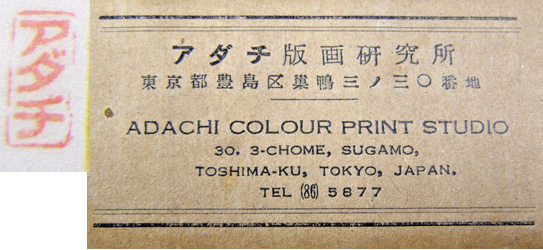

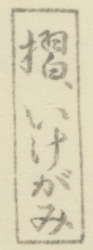

Assistance in PrintProduction

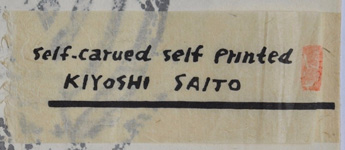

Saitō created over 1000prints during his lifetime. As thenumber of his works grew he must have used multiple assistants, at least in theprinting of large editions. Kazuyuki Ohtsu(b. 1935), now a woodblock artist in his own right, was his assistant for fortyyears from 1958 until Saitō’s death and printed many of his works. The AdachiPrint Institute (Adachi Colour Print Studio) also printed a number of hisworks, including print IHL Cat. #1514 in this collection and their mark, sometimes accompanied by a label pasted to the verso, appears on those prints, as shown below. “Suri Ikegami” (Printer Ikegami) 摺 いけがみ appears on a number of Saitō’s works, as shown below, but beyond thepresence of his stamp on the verso of some of Saitō’s prints (see IHL Cat. #1648) nothing appears about him in theliterature. As also shown below, a "self-carved self printed KIYOSHI SAITO" label can be found on a number of his earlier prints.

In his interview with Statler in 1956, Saitō commented on his use of “artisans”– “It’s not that I object to artisans in principle. I’m perfectly willing that they copy mysimpler things. But when I’m trying fora new or complicated effect I have to do the work myself even though I don’tespecially enjoy it.”18

It is not clear to me at what age Saitō stopped designing and/or producing prints. The last dated prints of his that I've come across are from his May in Aizu series that he created from 1988 into 1994 (see May in Aizu (I), 1988 and May in Aizu (9), 1994 above) when he was in his eighties.

Kiyoshi Saitō died on November 14, 1997 at theconclusion of a major retrospective in Tokyo at the Wako Department Store andshortly after he opened the Kiyoshi Saitō Museum of Art in Yanaizu which housesa collection of 850 of his works. (Go to https://www.town.yanaizu.fukushima.jp/bijutsu/tocurators/en/profile/)

In1956, Saitō told Statler “I’ve always done the kind of work I want to.” Perhapsthis is a fitting epitaph for his long and distinguished career.

Collections

Saitō donated prints and blocks to variousmuseums in Japan and the United States throughout his lifetime. His work can be found in numerous collectionsincluding The Ringling (whose collection includes a number of early and rare works); The Museum of Modern Art, New York; National Portrait Gallery, Washington D.C.,National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.; Cincinnati Art Museum, Museum ofFine Arts, Boston; Philadelphia Museum of Art; Fine Arts Museums of SanFrancisco; New York Public Library; Art Institute of Chicago; Carnegie Museum of Art; Indianapolis Museum of Art; Portland ArtMuseum, Portland, Oregon; Cleveland Museum of Art; University of Michigan Museum of Art; Fukushima Prefectural Museumof Art; Kanagawa Prefectural Museum; British Museum; Art Gallery of GreaterVictoria; Gallery of New South Wales; Tikotin Museum of Japanese Art, FukushimaPrefectural Museum of Art, Kanagawa Prefectural Museum of Art; The NationalMuseum of Modern Art, Tokyo

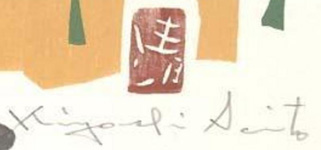

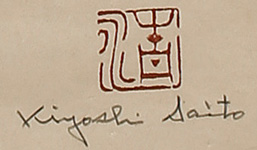

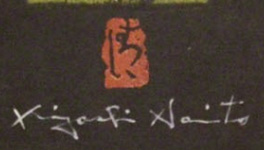

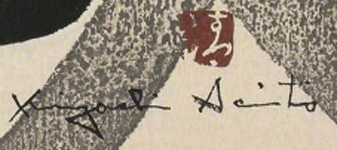

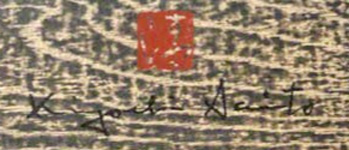

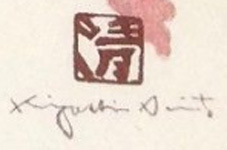

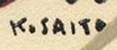

Signature and Seals

Saitō's works are generally signed or printed with his name "Kiyoshi Saito" and carry his "kiyoshi" 清 seal. A stamped "K. Saito" generally appears on the woodblock cards he created.

7 Kiyoshi Saito 齋藤清版画集 [Saitō Kiyoshi hangashū], Oliver Statler and Chisaburō F. Yamada, Kōdansha, 1957.

8 Op. cit., Merritt, p. 244.

9 Kiyoshi Saitō Museum of Art, Yanaizu website https://www.town.yanaizu.fukushima.jp/bijutsu/en/about/profile/]10 The Bienal de São Paulo was initiated in 1951 and is the second oldest art biennial in the world after the Venice Biennial, which was set up 1895 and served as its role model. http://www.biennialfoundation.org/biennials/sao-paolo-biennialv/11 A critique that could better be leveled at the idyllic prints of the shin hanga movement.12 Op. cit., Statler, p. 54.13 Op. cit, Till, p. 4.

14 Kiyoshi Saito Holds Unique Place In History of Contemporary Prints, appearing in The Japan Times, October 29, 1967, p. 5.

15 Ibid.

16 Op. cit., Statler, p. 57.

17 The Modern Japanese Print - An Appreciation, James Michener, Charles E. Tuttle Co., 1968, p. 13.

18 Op. cit. Statler, p. 54.

Last revision:

3/19/2020

9/13/2018

1938 UofM 800x697 web.jpg)

1938 UofM 800x687 web.jpg)

untitled19-959cc28b8c81e624.jpg)

1958 800x606 web.jpg)