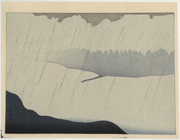

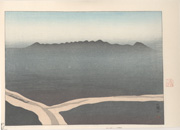

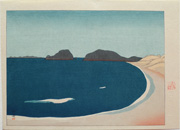

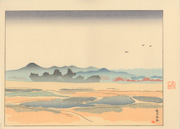

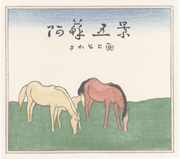

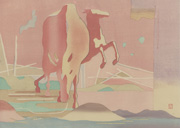

from the series Five Views of Aso, 1950

(envelope image and top print)

IHL Cat. #2379 and 2310

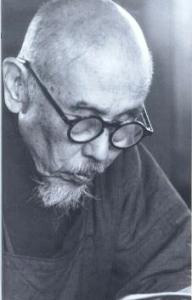

Profile

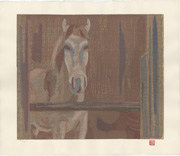

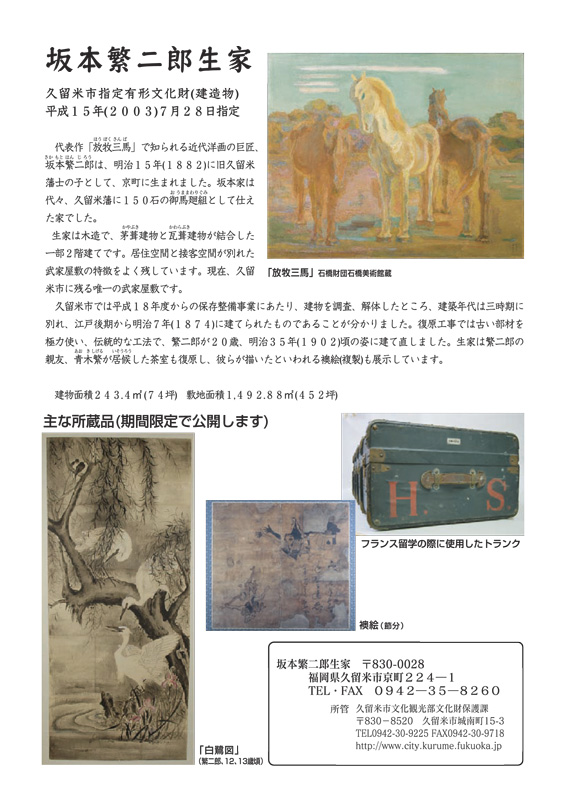

| Best known as a Western-style (yōga) painter who established his own style early in his career, his three years in Paris (1921-1924) reinforced that style. Despite gaining acclaim after moving from his hometown of Kurume City in Fukuoka Prefecture to Tokyo, he was never comfortable in the limelight and returned home shortly after his return from Paris at the age of 42, where he was to remain until his death at the age of 87. In 1956 Sakamoto received the government's Order of Cultural Merit. Sakamoto is best known for his paintings and prints of horses through which, in the artist's words, he "express[ed] my world formed in my mind." Sakamoto came to prints early in his career through his association with the art and literary journal Hōsun and the artists Yamamoto Kanae and Ishii Hakutei. As with other painters of the period who made prints, his prints were created with the cooperation of carvers and printers and were generally not self-carved and printed. |

Biography

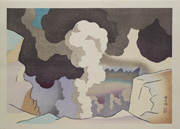

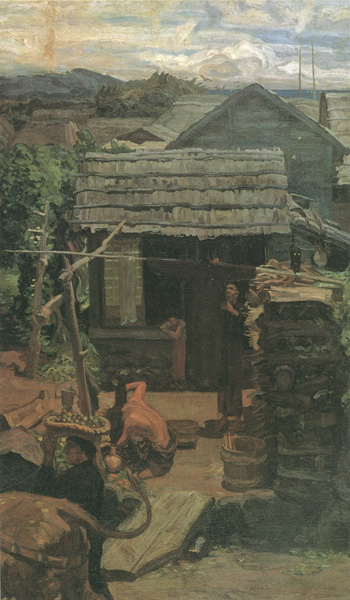

| A Section of Oshima Island, 1907 Sakamoto Hanjiro (1882-1969) oil on canvas, 116.3 x 73.0 cm Fukuoka Art Museum | "In the summer of 1906, Sakamoto, then aged 24, took a sketching trip to Izu Oshima with his artist friend Morita Tsunetomo (1881-1933). [A Section of Oshima Island] is one of the works which ensued as a result of this trip. With a smoking volcano, Mt. Mihara, in the background, the painting depicts a scene full of customs particular to the Izu Oshima region at that time - the tight-sleeved black kimonos and the way of carrying goods on one's head, for example. While the contrast of colors in this painting is relatively subdued, the objects are finely sketched in detail, revealing how the artist had already developed an acute eye for observation and a strong interest in expression."2 In 1910, Hanjirō was to marry and send for his mother to live with him and his wife in Tokyo. Exhibiting painting in the Ministry of Education’s Fine Arts Exhibition, Bunten, he was to win prizes in 1910 and 1911. In 1912, his painting Usurebi (Dim Sum) won extravagant praise from the great novelist Natsume Sōseki (1867-1916) and he gained sudden fame. In 1914 the now well-known Hanjirō participated, with a number of Western-style artists including Yasui Sōtarō (1888–1955) and Umehara Ryūzaburō (1888-1986), in the formation of the Nikakai (Second Division Society) which was founded in opposition to the conservative Bunten and welcomed European avant-garde ideas. |

Just as they say, Paris is indeed a city of flowers. But it is a flower without any scent. The moon glows, the snow falls. But those are just natural phenomena. One can draw nothing that speaks to a person’s heart … And especially when it comes to an abundance of natural beauty, no country is as blessed as Japan. – the artist3

Despite believing that he had already “established his method of creation,” Hanjirō, at the age of 39, departed for France in July of 1921, arriving in Paris in September. He moved into a house with a studio in the 14th aarrondisement already occupied by several other Japanese artists and entered the progressive Académie Colarorossi where he studied for six months with Charles Guérin (1875-1939), a leading figure in the Société des Artistes Français. For the remainder of his three years in Paris he “wandered the streets and outskirts of Paris, and visited museums and galleries…” and painted.4 Two noted works created during his Paris sojourn are Burutanyu fūkei (Brittany Landscape) and Bōshi o moteru onna (Woman with Hat), pictured below.

Summing up Hanjirō’s time in France, curator and art historian Shunrō Higashi wrote, while many Japanese artists “were bent on imitating the forms of Cubism and Fauvism…” [Sakamoto] “understood the gap between Japan and the West, especially with France” and was clear on his “own position on art from the outset. From his standpoint, Sakamoto’s concern was to express on canvas ‘human beings,’ a goal that had been lost after the advent of Cézanne. His discovery of Corot as a pioneer who had carried out this task doubtless achieved the objective of Sakamoto’s overseas study. From that period to his final years Sakamoto repeatedly talked about Corot, for whom his esteem never waned.”5

Return to Japan

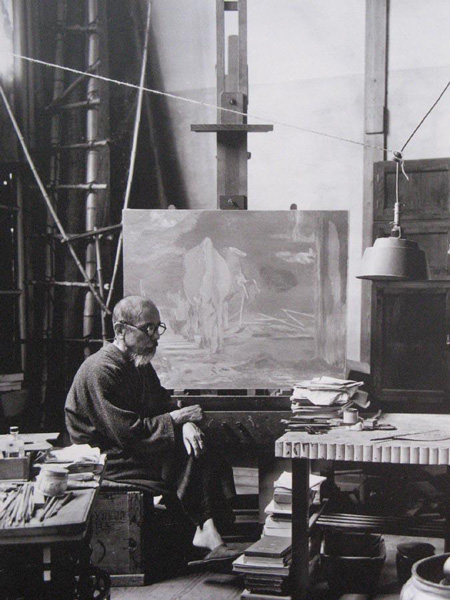

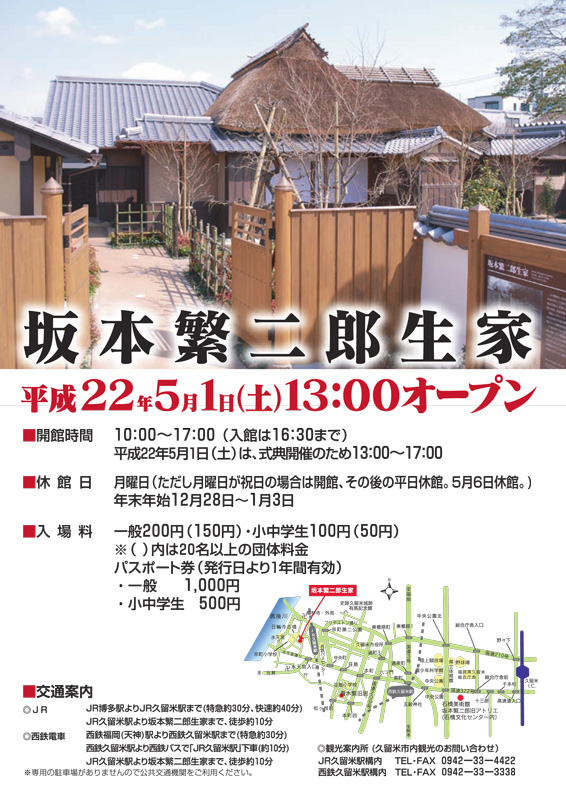

Leaving France in 1924 and returning to Tokyo, “Sakamoto mounted a successful show of works he had painted in France” at that year's Nikakai exhibition, leading a contemporary critic to comment that “he had ‘transcended the ‘-isms' and was able to express his own personality.”6 Yamamoto Kanae wrote: "As everyone says, his paintings are spiritual. Still they are nothing but pictures. They do not imply anything literary. Mr. Sakamoto painted only what he saw with his eyes. . . . However, 'seeing' is of immense significance, and lies therein a reality that has been depicted by Mr. Sakamoto for the first time."7Despite being well received in Tokyo, the center of Western-style painting in Japan, Sakamoto was most happy out of the limelight and longed for his pastoral childhood home of Kurume where he returned in 1924 and, near which he was to remain for the rest of his life, establishing a studio in Yame in Fukuoka in 1931.

“Painting became for him a mystical experience having little relevance to the world of galleries, admirers, journalists, museums, and patrons.”8 Pursuing his love of horses, he dedicated himself almost exclusively to their depiction, so much so that he “won an unenviable notoriety as a painter ‘picturing nothing but horses.’”9

As I am painting only horses, it has been said that my production is merely repetitive. If I am laughed at for this, I am not hurt at all, bit if the meaning of such criticism is that the essence of my pictures remains somehow merely conservative, I will be dismayed indeed. I do not care if I repeat the same subject. If this repetition can endlessly improve the content of my art, then, as a painter, I am, rather, proud. I do not necessarily disregard the opinion that painters, as members of society, should take up social problems as motifs, but what matters after all is the intrinsic nature of their work. Even if a painter pictures one stone, his work, depending on his attitude, many act on contemporary society.10

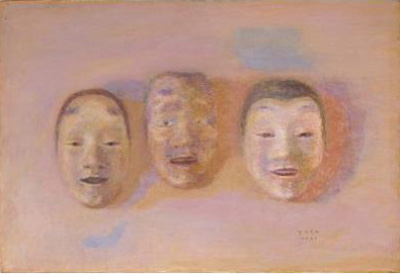

During the Second World War Hanjirō painted numerous still lifes. In the postwar period his work took on a distinctive Eastern feeling in his paintings of Nō drama masks, with their strangely unreal quality.

In 1944 Hanjirō left the Nikakai. In 1946 he was offered membership in the Japan Art Academy, but he declined and after the war remained unattached to any organization, exhibiting independently. In his late years he was much honored, being awarded the Awarded the Asahi Prize in 196211, the Mainichi Fine Arts Grand Prize in 196312 and the Order of Cultural Merit in 1956, but throughout he was unchanging in his rigorous way of life and independent course.

In 1944 Hanjirō left the Nikakai. In 1946 he was offered membership in the Japan Art Academy, but he declined and after the war remained unattached to any organization, exhibiting independently. In his late years he was much honored, being awarded the Awarded the Asahi Prize in 196211, the Mainichi Fine Arts Grand Prize in 196312 and the Order of Cultural Merit in 1956, but throughout he was unchanging in his rigorous way of life and independent course.

Until his death in Yame on July 14, 1969, "Sakamoto’s palette remained austere and his subject matter ever more tightly controlled, yet many Japanese viewers found, and continue to find, a quiet and searching authenticity in his work that places him at the forefront of the modern Japanese masters.”13

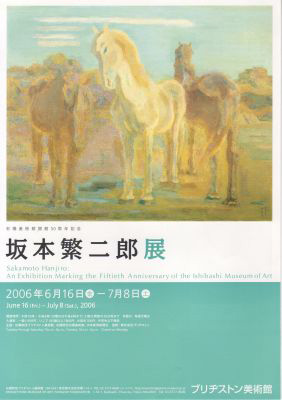

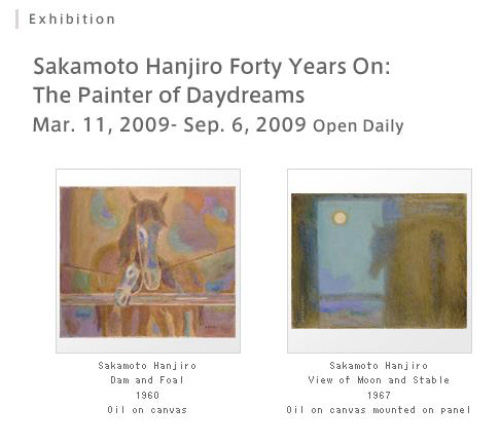

Recent Exhibitions

Hanjirō |  |  Sakamoto |  Sakamoto |  Sakamoto |  Sakamoto |  |