About These Prints

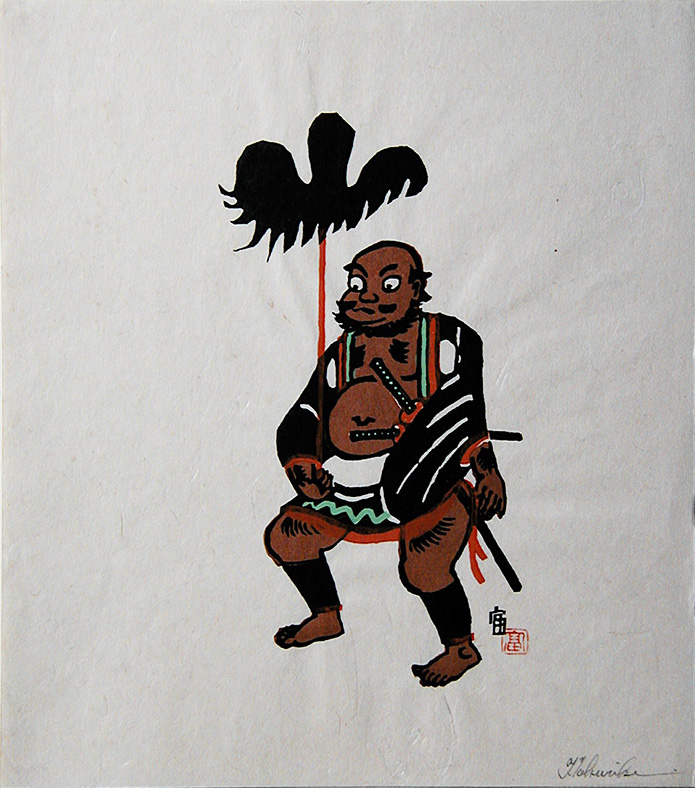

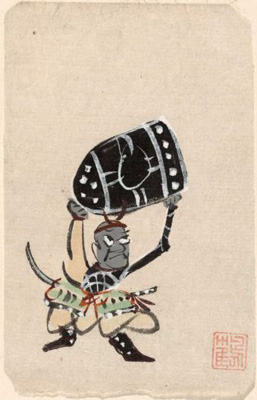

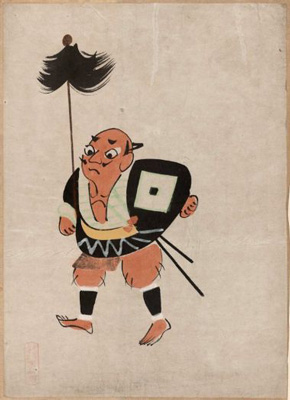

These three prints are Tokuriki's modern-day take on the traditional folk Ōtsu-e paintings and prints that take their name from the town of Otsu, where they originated in the mid-17th century. Each of the above prints takes it theme from earlier works, several of which are shown below. Subjects were generally taken from "Buddhist themes, andlater by a wide variety of folk heroes, Shinto kami, sages, and demons; popular womenappearing in ukiyo-e..." [ref. the section "Ōtsu-e" below for source]Each figure in the above prints serves as a talisman:

Wisteria maiden (Fuji musume) - adds to your amiability and helps you get a good romantic partner.

Standard bearer (Yarimoichi yakko) - provides safety during travel. These unpopular figures led the traveling daimyo processions, ordering all bystanders to bow down as noblemen passed with their long retinues.

Benkei and the Bell (Tsurigame Benkei) - provides physical strength. The story is told of how the monk-warrior Benkei took the famous bell of Mii-dera and dragged it up to the summit of mount Hiei. He struck the bell and then got angry when he heard it ringing “eeno eeno”, which means “I want to go back” in the Kansai dialect. In his anger, Benkei threw the bell down to the bottom of the valley.

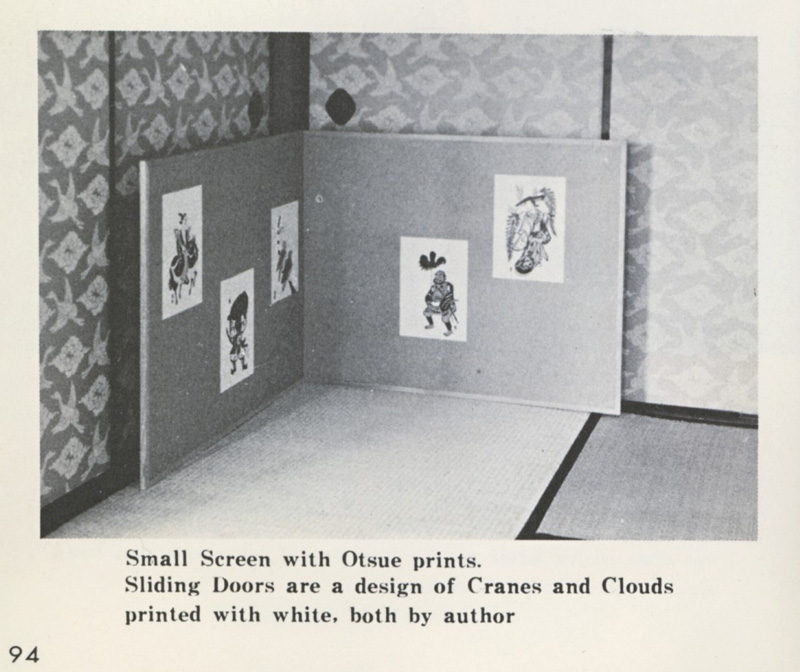

| This collection's ōtsu-e in a photo from the artist's 1968 book Wood-block Printing. | Tokuriki's shikishiban (square) format edition of this collection's print, #678 Standard Bearer(Yarimochi yakko) |

Ōtsu-e

Source: Review of: Ishimaru Shōun 石丸正運, Ōtsu-e: Kaidō ni umareta minga 『大津絵-街道に生まれた民画』 [145-46], Harrie A. Vanderstappen, appearing in Asian Ethnology 1056 http://nirc.nanzan-u.ac.jp/publications/afs/pdf/a1056.pdf"The name Ōtsu-e derives from the town of Otsu, a community at the southern tip of Lake Biwa that was the last station on the old Tokaido before one reached Kyoto. On the outskirts of the town the road forked, with one branch leading to Kyoto and the other to the more southerly area of Fushimi. It was in shops near this fork that the Ōtsu-e paintings were produced, giving rise to an earlier alternative name ofoiwake-e (fork pictures). The place is still marked by a sign. These shops are already mentionedin the Omi yochi shiryaku of 1734, and pictures of them appear in early- and mid-Edo illustrative scrolls, such as the Ise sangu meisho zue of 1797.

The first Ōtsu-e are believed to have been produced in the middle of the seventeenth century or slightly earlier, but some writers place the date as late as the second half of the seventeenth century. Dated prints from this early period are not extant, however. It is generally agreed that the early Ōtsu images were largely Buddhist in content. It is hard to imagine that giga or manga (cartoon) images might have preceded these Buddhist images. Some scholars have suggested that the appearance of these popular, quickly produced Buddhist images was connected with the persecution of Christianity - housesearches for hidden Christians supposedly made it necessary to display Buddhist images to prove one's Buddhist faith. But there is little evidence to support such a Christian connection, and the earliest records of Ōtsu Buddhist images are from no earlier than the 1660s, decades after the Christian persecution.

Three basic features characterized the Ōtsu-e. First, they were a mass-produced localproduct sold, as mentioned above, at a well-known intersection near Otsu. Second, theirsubject matter was characterized in the early phase by an emphasis on Buddhist themes, andlater by a wide variety of folk heroes, Shinto kami, sages, and demons; popular womenappearing in ukiyo-e became part of the Ōtsu-e repertoire in the eighteenth century, anddidactic poems were added in the genre's final phase. Thirdly, throughout the history of the Ōtsu-e there is a consistency in the manner of production. One or more sheets of handmade paper (called makotorinoko or maniaigami) were used, and stencils were employed for areas of color. At times the images were partially wood-block printed, but final finishing was almost always done with brush and ink to add lively strokes emphasizing shape and outline."

The first Ōtsu-e are believed to have been produced in the middle of the seventeenth century or slightly earlier, but some writers place the date as late as the second half of the seventeenth century. Dated prints from this early period are not extant, however. It is generally agreed that the early Ōtsu images were largely Buddhist in content. It is hard to imagine that giga or manga (cartoon) images might have preceded these Buddhist images. Some scholars have suggested that the appearance of these popular, quickly produced Buddhist images was connected with the persecution of Christianity - housesearches for hidden Christians supposedly made it necessary to display Buddhist images to prove one's Buddhist faith. But there is little evidence to support such a Christian connection, and the earliest records of Ōtsu Buddhist images are from no earlier than the 1660s, decades after the Christian persecution.

Three basic features characterized the Ōtsu-e. First, they were a mass-produced localproduct sold, as mentioned above, at a well-known intersection near Otsu. Second, theirsubject matter was characterized in the early phase by an emphasis on Buddhist themes, andlater by a wide variety of folk heroes, Shinto kami, sages, and demons; popular womenappearing in ukiyo-e became part of the Ōtsu-e repertoire in the eighteenth century, anddidactic poems were added in the genre's final phase. Thirdly, throughout the history of the Ōtsu-e there is a consistency in the manner of production. One or more sheets of handmade paper (called makotorinoko or maniaigami) were used, and stencils were employed for areas of color. At times the images were partially wood-block printed, but final finishing was almost always done with brush and ink to add lively strokes emphasizing shape and outline."

Older Ōtsu-e

Print Details

| IHL Catalog | #677, #678, #679 |

| Title | #677 Wisteria Maiden (Fuji musume) #678 Standard Bearer (Yarimochi yakko) #679 Benkei Carrying Bell(Tsurigame Benkei) |

| Series | |

| Artist | Tokuriki Tomikichirō (1902-2000) |

| Signature | stamped (or carved) Tomoe |

| Seal | |

| Date | c. 1955 |

| Edition | assumed original edition |

| Publisher | self-published |

| Impression | excellent |

| Colors | excellent |

| Condition | good - foxing present in #677 and #678 |

| Genre | Otsu-e; sosaku hanga |

| Miscellaneous | |

| Format | chuban |

| H x W Paper | 11 x 7 7/8 in. (27.9 x 20 cm) each print |

| Collections This Print | |

| Reference Literature | |