Overview

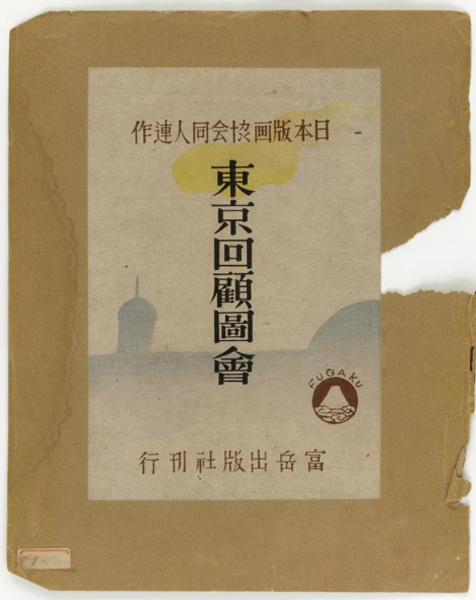

Tokyo kaiko zue 東京回顧圖會, a portfolio of fifteen prints created by nine artists [all members of Nippon Hanga Kiyōkai (the Japan Print Association)], is variously translated as Scenes of Last Tokyo, Recollections of Tokyo, Retrospective Scenes of Tokyo, and Scenes of Lost Tokyo. (The cover of the portfolio containing the prints carries the translation Scenes of Last Tokyo but "Last Tokyo" is thought to be a "typographical error" for "Lost Tokyo.")1 Though the target audience for the portfolio was the Occupation forces2 the portfolio, according to Lawrence Smith3, contained "a coded message to Japanese readers" in the subjects depicted in some of the prints and in its introductory message (see Statement of the Artists below.) This coded message, composed shortly after the surrender of the Japanese in August 1945, by the leading sosaku hanga (creative print) artist Onchi Koshiro (1891-1955), was a hope for the retention of some of the imperial institutions in the remaking of Japan.Published in December 1945 by the Tokyo publisher Uemura Masurō, Tokyo kaiko zue was designed to be very similar in spirit to the 1929-1932 series Shin Tokyo hyakkei (One Hundred Views of New Tokyo) which was also a collaboration between multiple artists4. Four of the same artists, Koshiro Onchi, Un’ichi Hiratsuka, Maekawa Senpan and Kawakami Sumio participated in both collaborations. Onchi rushed the prints for Tokyo kaiko zue into production working with the publisher Uemura Masurō, proprietor of Fugaku Shuppansha, a newly formed company that Onchi helped establish.

1 The Artist's Touch, The Craftsman's Hand: Three Centuries of Japanese Prints from the Portland Art Museum, Maribeth Graybill, Portland Art Museum, Oregon, 2011, p. 294.

2 The artists agreed to allow reissuing the prints for sale at the U.S. Army Post Exchange in Tokyo.

3 Japanese Prints During the Allied Occupation 1945 – 1952, Lawrence Smith, The British Museum Press, 2002, p. 23–24.

4 Due to shortages after the war, the paper is quite different from that used for the originals published in the 1929-1932 series Shin Tokyo hyakkei (One Hundred Views of New Tokyo), and the effect is consequently flatter and less vibrant than in the first state.

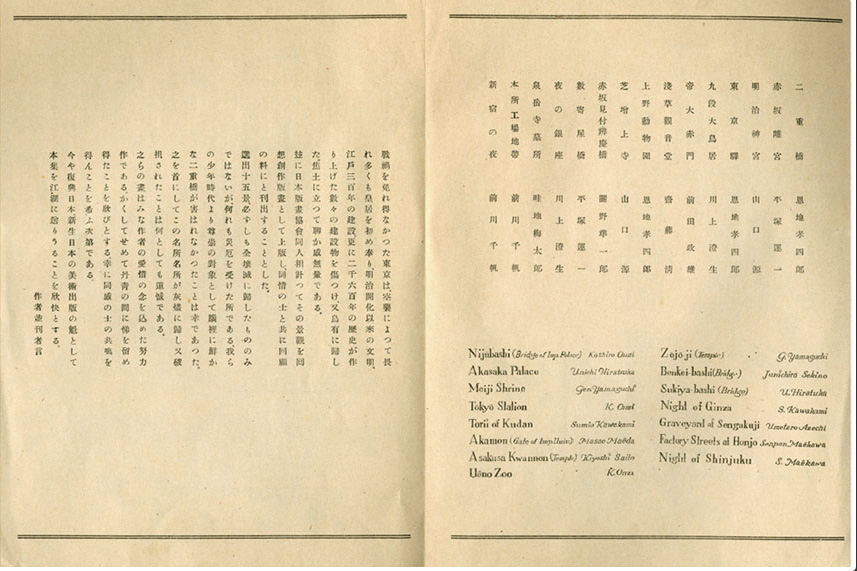

Statement of the Artists (a coded message)

Source: Japanese Prints During the Allied Occupation 1945 – 1952, Lawrence Smith, The British Museum Press, 2002, p. 23–24.While the print titles are provided in English, as well as Japanese, the introduction included in the portfolio is in Japanese only. The following translation is provided by Lawrence Smith and is described as being "as literal as is possible, given the poeticnature of the language used."

| As for Tokyo, which did not escape the ravages of war, an awesomenumber of buildings were damaged or reduced to ashes by air raids,starting in reverence with the Imperial Palace, then those of the MeijiEnlightenment, of 300 years of the Edo period, and furthermore thestructures produced by 2,600 years of history. To stand on the burntearth is an unfathomable feeling. Here, members of the Japanese Print Association planning together haveput those scenes into woodblocks as a reminiscence of Creative Prints,and have decided to publish them as a retrospective document for thosewho share those regrets. The fifteen selected views were not all ofcourse totally destroyed, but all of them received some misfortune. Itwas a lucky thing that Nijubashi, remaining so vividly in our heartsfrom our childhood as a revered object of worship, was not damaged. This apart, it is deeply regrettable that these famous places wereeither completely destroyed or damaged. These pictures are all theproducts of the efforts of artists motivated by this sadness throughloss. We in the art world rejoice that we can serve our elders withfilial piety in this way. We are happy to be able to request thesympathetic understanding of those with the same feelings. Now, as thefirst artistic banner of a revived Japan with a new life, we arepleased to offer this collection to the public for sale. The artists and publishers. |

The fifteen places chosen for this set were mostly new editions ofdesigns which had appeared in the series One Hundred Views of New Tokyo(Shin Tokyo hyakkei), originally published in the years 1929-1932, andwere to date the most ambitious project of the Creative Print artistsin the Japanese Print Association. This in part explains the referenceto ‘a reminiscence of Creative Prints’ (kaiso Sosaku Hanga.) Theoriginal one hundred views had covered many aspects of Tokyo life, andno more than ten could be considered to have had imperial ormilitaristic connotations. This makes all the more noticeable thechoice in 1945 of six places with serious imperial resonances out of atotal of only fifteen, especially as the titles are given in English. The six are the Nijubashi Bridge at the Imperial Palace referred to inthe above text, the Akasaka Palace (residence of the Crown Prince), theMeiji Shrine, the Torii (Gateway) at Kudan, the Gate of the ImperialUniversity (alma mater of the most senior bureaucrats of the militaristera), and the Graveyard of Sengaku-ji, burial place of Japan’s mostcelebrated paragons of loyalty. The inclusion of Kudan is particularlyaudacious, but also poignant, for it was there that Onchi’s son killedin the war would have been enshrined, as well as the war dead relatedto others of the artists. This inclusion could not be a mistake, forit was not a design from the old series, and had to be added, howeverantique and apparently innocuous the sentiment with which it isloaded. The remainder are of scenes of Tokyo from around 1930, mostlyby then vanished.

The innovation of short English titles is obviously intended to attractpotential customers from among the occupying forces and, possibly forthat reason, too, the rather dark and apprehensive atmosphere of theoriginals is softened and lightened. This does seem a preview of thesunnier mode of the future, which was to prove attractive to foreigncustomers. However, there seems little doubt that the set is aimed at nostalgic native buyers, for scenes of Tokyo, new orold, were not to be much produced after this for many decades.

It is necessary to ask who actually wrote this significant paragraph. It can hardly have been anyone but Onchi Koshiro. He was by far themost literary of all the print artists, and was the acknowledged leaderof the Creative Print movement. He was the only one who, as the son ofa Court official, would have known and revered the Nijubashi,‘remaining so vividly in our hearts sine our childhood’. Nobody elseinvolved would or could have written with such oblique authority of aJapan which he assume would not be changed substantially by theOccupation.

Statement of the Artists - Alternate Translation

Source: Modern JapaneseWoodblock Prints - The Early Years, Helen Merritt, University of Hawaii Press, 1998pp. 282-283| During the war, air attacks destroyed or damaged much of the city ofTokyo, including many valuable structures which held a special meaningfor us. Among these were, regrettably, the Imperial Palace, which hasbeen held in much veneration, and many landmarks of Meiji culture andof the three hundred years of the Edo Period. Beyond this, a number ofstructures which spanned the whole 2600 years of our history weredamaged or lost. As we stand in the midst of this devastation, we aresilent because our feelings are inexpressible. The Japan Print Association has, therefore, through the cooperation ofits members, decided to publish a series of prints to commemorate someof the features of Tokyo which have now disappeared. In addition, itwould be a pleasure for us should we be successful in restoring thewood-block print to even a vestige of its former glory. Of the fifteen subjects selected, some were fortunate enough to retaintheir form, though all suffered some damage and are situated in areasin which there was great destruction. It is a great relief that theNijubashi, which has been deep in our hearts since childhood, was notspoiled. Yet it is regrettable that so much of our preciousarchitecture was destroyed during the conflict. These works are all the result of our sincerity, enthusiasm, and lovefor art. We are happy that others will share this pleasure with us. Japan is now well on the way to reconstruction. We are pleased that weare able, by the publication of this set of prints, to make an artisticcontribution to our land. - The Artists |

Information on Colophon

The set was issued with a four page leaflet (see cover and pages 2 and 3 below), page 4 of which contained the colophon (written in Japanese) with the following information:

Nihon Hanga Kyōkai Dōjin Jikoku Rensakuhin

[A Joint Work, Self-Carved, by Members of the Japan Print Society]

Shōwa nijūnen jūnigatsu jūgonichi insatsu

[printed on Showa 20, 12th month, 15th day (Printed December 15, 1945)]

昭和二十年十二月二十日版行

Shōwa nijūnen jūnigatsu hatsuka hankō

[published on Showa 20 [1945], 12th month, 20th day (Published December 20, 1945)]

Tōkyō-to, Suginami-ku, Kamiogikubo 2-148

[Publisher: Uemura Masurō]

Tōkyō-to, Suginami-ku, Kamiogikubo 2-148

[Publishing House: Fugaku Shuppansha]

電話荻窪五六〇一番

[Telephone Ogikubo 5601]

[With assistance in woodblock printing from Takamizawa Mokuhan Honsha Kōbō]

The Set as Originally Issued

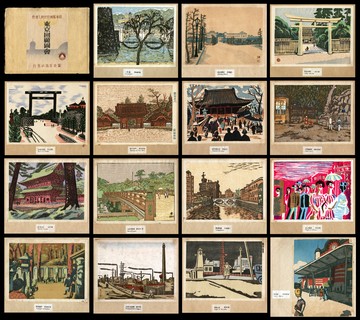

| Cover, Table of Contents and Statement of Artists and Colophon from the accompanying 4 page leaflet | Entire Print Set and portfolio case |

List of Prints in Series

| Artist | Print Title | Blocks Used for Printing |

| Onchi Kōshirō (1891-1955) | Nijubashi (Bridge to the Imperial Palace) | recut blocks of 1929 design1 |

| Onchi Kōshirō (1891-1955) | Tokyo Station | original blocks for 1929 design1,2 |

| Onchi Kōshirō (1891-1955) | Ueno Zoo | recut blocks of 1929 design1 |

| Hiratsuka Un'ichi (1895-1997) | Akasaka Palace | recut blocks by Maeda Masao of 1929 design1 |

| Hiratsuka Un'ichi (1895-1997) | Sukiya Bridge (Sukiyabashi) | recut blocks by Maeda Masao of 1929 design1 |

| Maekawa Senpan (1888-1960) | Factory Street at Fukagawa | recut blocks of 1929 design1 |

| Maekawa Senpan (1888-1960) | Night at Shinjuku | recut blocks of 1929 design1 |

| Kawakami Sumio (1895-1972) | Night at Ginza | recut blocks of 1929 design1 |

| Kawakami Sumio (1895-1972) | Torii at Kudan | new design and blocks |

| Yamaguchi Gen (1896-1976) | Zozoji (Temple) | new design and blocks |

| Yamaguchi Gen (1896-1976) | Meiji Shrine | new design and blocks |

| Azechi Umetarō (1902-1999) | Graveyard at Sengakuji | new design and blocks |

| Maeda Masao (1904-1974) | Red Gate, Tokyo University | new design and blocks |

| Kiyoshi Saitō (1907-1997) | Asakusa Kannon Temple | new design and blocks |

| Sekino Jun’ichirō (1914-1988) | Benkei Bridge | new design and blocks |

1 designs from the 1929 - 1932 series Shin Tokyo hyakkei (One Hundred Views of New Tokyo)

2 according to Amy Newland, "The block for Onchi's print Tokyo Station, a building which still stands today, was the only selection from the original set (the 1929-1932 Shin Tokyo hyakkei series) which did not require recarving." (Source: Ukiyo-e to Shin hanga - The Art of Japanese Woodblock Prints, Amy Newland and Chris Uhlenbeck, Brompton Books Corporation, 1990 p. 208.)