Sino-Japanese War (日清戦争) Prints in Collection

(Presented in rough chronological order of military engagements)Battle of Songhwan 成歓作戦 (and occupation of Asan): July 26-29, 1894 (the first major land battle)

Great Imperial Victory at the Fierce Battle at Pyong-Yang, November 1894 IHL Cat. #305 |

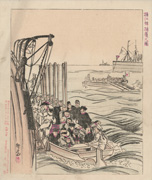

Naval Battle of the Yellow Sea 黃海海戰: September 17, 1894 (a decisive naval battle)

Note: The Battle of the Yellow Sea was also known as the Battle of Haiyang Island, Battle of Dadonggou, Battle of Taigozaoki and Battle of Yalu, all landmarks near the engagement.

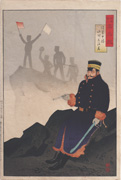

The Manchurian Campaign, Part 1: October 23 - December 1894 (Japanese troops conquered Hushan, Kiuliencheng, and Fenghuangcheng in quick succession, but upon reaching Sauhoku, they were spied on and attacked by mounted Manchurian soldiers)

Kiuliencheng, October 1894 Nobushige (active 1894-95) IHL Cat. #350 | IHL Cat. #1356 |

Valiant Battle at Kiuliencheng, October 1894 IHL Cat. #1948 Unread (Hōei?) | | IHL Cat. #110 |

The Manchurian Campaign, Part 2: December 8 - March 9, 1895 (preparations for Weihaiwai campaign)

| The Attack on Weihaiwei: The Taking of the Hundred Foot Cliff, 1895 [Captain Higuchi saves a child] IHL Cat. #2163 | Captain Higuchi, in the Midst of the Attack, Personally Holds a Lost Chinese Child, July 1895 IHL Cat. #1811 |

| Japanese Forces Overpower Taiwanese Bandits Near Xinzhu, August 1895 Kobayashi Kiyochika (1847-1915) IHL Cat. #97 | | |

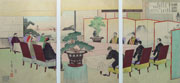

Kubota Beisen's "Illustrated Account of the Sino-Japanese War"

| | Illustrated Account of the Sino-Japanese War, Volume 5, 1895 Kubota Beisen (1852-1906) IHL Cat. #548 | Illustrated Account of the Sino-Japanese War, Volume 7, 1895 Kubota Beisen (1852-1906) IHL Cat. #1012 |

Illustrated Account of the Sino-Japanese War, Volume 8, 1895 Kubota Beisen (1852-1906) IHL Cat. #549 | Kubota Beisen (1852-1906) IHL Cat. #906 |

Asai Chū's "Some Sketches of the Japan-China War"

| Some Sketches of the Japan-China War, Volume 1 IHL Cat. #871 | Some Sketches of the Japan-China War, Volume 3 IHL Cat. #872 | Some Sketches of the Japan-China War, Volume 4 IHL Cat. #873 |

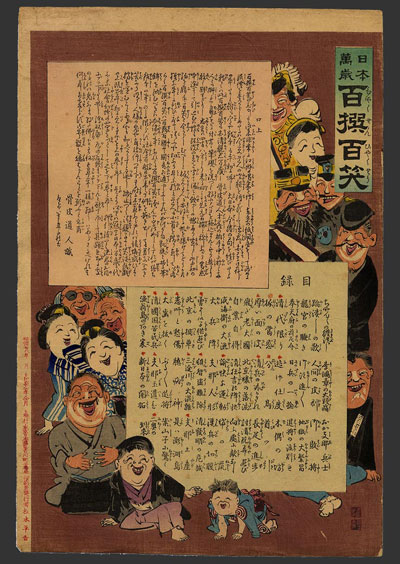

Kobayashi Kiyochika's Satirical Print Series "Long Live Japan: One Hundred Victories, One Hundred Laughs."

To go to the article on this print series click on the above image

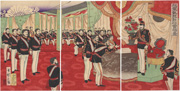

Sino-Japanese War Prints (Senso-e)

The historian Donald Keene has estimated that an average of ten new prints were created every day during the ten months (July 1894 - April 18951) of the Sino-Japanese War, amounting to around 3000 different images. Woodblock publishers recognized the opportunity for revitalizing flagging sales of prints and pushed production of war related prints. As stated in the literary journal Waseda bungaku in its November 1894 issue, "The nishiki-e, formerly devoted chiefly to actor portraits and the depiction of mores, now treat almost nothing but the Sino-Japanese war or related persons and incidents."2Immense Popularity

In May 1895, Lafcadio Hearn wrote, "The announcement of each victory resulted in enormous manufacture and sale of colored prints, crudely and cheaply executed, and mostly depicting the fancy of the artist only." It seemed that "[a]ny thing having to do with the war would sell" and it was only the government "censors who were slow to clear works for printing" that slowed down sales.3 "Great crowds gathered before the print shops, and pickpockets thrived.”4The famous author Tanizaki Jun'ichirō (1886-1965) remembers his excitement over the war prints:

| The Shimizu-ya, a printshop at the corner of Ningyō-chō, had laid a large stock of triptychs depicting the war, and had them hanging in the front of the shop. They were mostly by Mizuno Toshikata, Ogata Gekkō, and Kobayashi Kiyochika. There was not one I didn't want, boy that I was, but I only rarely got to buy any. I would go almost every day and stand before the Shimizu-ya, staring at the pictures, my eyes sparkling.5 |

2 "Crows, Cranes & Camellias. The NaturalWorld of Ohara Koson 1877-1945. Japanese Prints from the Jan PerreeCollection", Amy Reigle Newland, Jan Perree & RobertSchaap, Amsterdam Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam 2001, p. 15.

3Professor Edward Seidensticker as quoted by Robert Vergez in his article "Images of the Sino-Japanese War – A Book Review," Ukiyo-e Art: A Journal of the Japan Ukiyo-e Society, No. Vol. 79, 1983, p. iii.

4 Ibid.

5 "Prints of the Sino-Japanese War," Donald Keene, appearing in Impressions of the Front: Woodcuts of the Sino-Japanese War, Okamoto, Shumpei, Philadelphia Museum of Art, 1983, p. 10.

"It is difficult to evaluate the artistic importance of the Sino-Japanese War prints. The Japanese critic Yoshida Susugu enthusiastically proclaimed Kiyochika's works to be at the very summit of the art of the wood-block print as developed in Japan, but surely no one would prefer to own one than a ukiyo-e by Utamaro, for example. In any case, they are not what most Westerners turn to when they begin to collect Japanese art. I began to collect them some fifteen years ago, when all other prints had soared in price beyond my range, although my taste for them had to be acquired. I have gradually come to savor these last manifestations of a great tradition.... The wartime prints, quickly made and inexpensively sold, represent a Japanese ideal, now all but lost, of making beautiful even the least expensive and least obviously artistic objects."

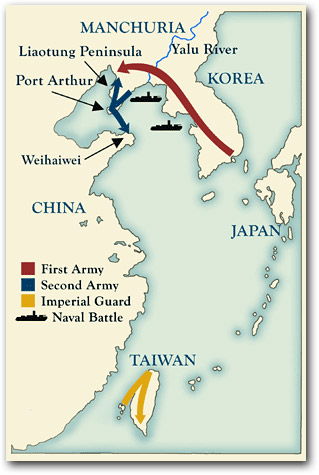

The Sino-Japanese War of 1894-95 was a result of Japan's emulation of the Western imperialism which sought to establish spheres of influence and seek territorial gain throughout Asia. The murder of Kim Ok-kyun, a pro-Japanese Korean leader, and Japan’s refusal to recognize China’s alleged suzerainty over the Korean Kingdom, provided the pretext for the one-sided Sino-Japanese War of 1894-1895. With three columns of army troops originating from, respectively, Seoul, Sak-ryong and Gen-san, and converging on Pyong-yang, Japan won a succession of decisive battles, and subsequently invaded the Liaotung peninsula in South Manchuria. However, the victory was largely determined by sea power. The vessels of the Ch’ing empire were no match for the modern Japanese fleet. In the major engagement off the Yalu River (also known as the Battle of the Yellow Sea), the Japanese navy virtually decimated the Peiyang (Northern) squadron, and thereafter took control of North China waters. Port Arthur, at the extreme end of the Liaotung peninsula, was captured from the landward side. Whatever was left of the Chinese fleet was bottled up at Weihaiwei in Shantung Province, south of Port Arthur across the Gulf of Pechili. The Japanese army surrounded the harbor by land, captured the forts, and bombarded the Chinese fleet which was sunk ingloriously in February 1895, essentially ending the war.

The 1894-5 war in Korea between China and Japan wasa key event in defining the politics of south Asia at the end of thenineteenth century. Japan'smilitary intervention in Korea was certainly not a sudden decision: itrepresented the culmination of more than a decade of pressure byadvocates of foreign expansion to mount a military campaign in Korea.Pro-war sentiment in Japan was fueled by a desire to secure Japan'sstrategic borders, which were defined in relation to the expansionistaims of Russia and the Western powers. Depending on the sympathies ofthe historian, Japan's Korean policy of the 1880s and 1890s has beenvariously interpreted as a classic example of aggressive imperialistexpansion, or as a sincere but misguided attempt to extend to theKoreans the benefits of reform and economic development that Japan hadenjoyed since the Meiji restoration of 1868 opened the country to theoutside world.

Collecting Prints of the Sino-Japanese War

Source: "Prints of the Sino-Japanese War," Donald Keene, appearing in Impressions of the Front: Woodcuts of the Sino-Japanese War, Okamoto, Shumpei, Philadelphia Museum of Art, 1983, p. 10"It is difficult to evaluate the artistic importance of the Sino-Japanese War prints. The Japanese critic Yoshida Susugu enthusiastically proclaimed Kiyochika's works to be at the very summit of the art of the wood-block print as developed in Japan, but surely no one would prefer to own one than a ukiyo-e by Utamaro, for example. In any case, they are not what most Westerners turn to when they begin to collect Japanese art. I began to collect them some fifteen years ago, when all other prints had soared in price beyond my range, although my taste for them had to be acquired. I have gradually come to savor these last manifestations of a great tradition.... The wartime prints, quickly made and inexpensively sold, represent a Japanese ideal, now all but lost, of making beautiful even the least expensive and least obviously artistic objects."

Comic Prints of the Sino-Japanese War

Artists, particularly Kobayashi Kiyochika (1847-1915), created numerous comic prints mocking the enemy during the war. For the most famous series of these comic prints (manga or giga) see the article The Series “One Hundred Victories, One Hundred Laughs.”Sino-Japanese War (1894-1895) - A Summary

Source: "Images of the Sino-Japanese War – A Book Review," Robert Vergez, Ukiyo-e Art: A Journal of the Japan Ukiyo-e Society, No. Vol. 79, 1983, p. ii.The Sino-Japanese War of 1894-95 was a result of Japan's emulation of the Western imperialism which sought to establish spheres of influence and seek territorial gain throughout Asia. The murder of Kim Ok-kyun, a pro-Japanese Korean leader, and Japan’s refusal to recognize China’s alleged suzerainty over the Korean Kingdom, provided the pretext for the one-sided Sino-Japanese War of 1894-1895. With three columns of army troops originating from, respectively, Seoul, Sak-ryong and Gen-san, and converging on Pyong-yang, Japan won a succession of decisive battles, and subsequently invaded the Liaotung peninsula in South Manchuria. However, the victory was largely determined by sea power. The vessels of the Ch’ing empire were no match for the modern Japanese fleet. In the major engagement off the Yalu River (also known as the Battle of the Yellow Sea), the Japanese navy virtually decimated the Peiyang (Northern) squadron, and thereafter took control of North China waters. Port Arthur, at the extreme end of the Liaotung peninsula, was captured from the landward side. Whatever was left of the Chinese fleet was bottled up at Weihaiwei in Shantung Province, south of Port Arthur across the Gulf of Pechili. The Japanese army surrounded the harbor by land, captured the forts, and bombarded the Chinese fleet which was sunk ingloriously in February 1895, essentially ending the war.

Japanese lines of attack

MIT Visualizing Cultures websiteJapan's Involvement in Korea

Source :Glimpses of the Sino-Japanese War in Korea, 1894-5, Beth McKillop and Hamish Todd, curators in theOriental and India Office Collections at The British Library, published on theFathom Knowledge Network website http://www.fathom.com/feature/122225/The 1894-5 war in Korea between China and Japan wasa key event in defining the politics of south Asia at the end of thenineteenth century. Japan'smilitary intervention in Korea was certainly not a sudden decision: itrepresented the culmination of more than a decade of pressure byadvocates of foreign expansion to mount a military campaign in Korea.Pro-war sentiment in Japan was fueled by a desire to secure Japan'sstrategic borders, which were defined in relation to the expansionistaims of Russia and the Western powers. Depending on the sympathies ofthe historian, Japan's Korean policy of the 1880s and 1890s has beenvariously interpreted as a classic example of aggressive imperialistexpansion, or as a sincere but misguided attempt to extend to theKoreans the benefits of reform and economic development that Japan hadenjoyed since the Meiji restoration of 1868 opened the country to theoutside world.

The Treaty Ending the War and the Tripartite Intervention

Source: "Images of the Sino-Japanese War – A Book Review," Robert Vergez, Ukiyo-e Art: A Journal of the Japan Ukiyo-e Society, No. Vol. 79, 1983, p. ii.With the defeat of the Chinese fleet, the war was over. Li Hung-chang, the Viceroy of Tientsin, was forced to negotiate with Japanese Prime Minister Ito Hirobumi and sign the Treaty of Shimonoseki (17 April 1895). This brought Japan not only Taiwan, the Pescadores, and a foothold in South Manchuria, but also a handsome indemnity (two hundred million taels), the recognition of Korea’s independence, and most importantly, the same privileges that the Western powers were enjoying in China. Korea became a Japanese protectorate in 1905 and was annexed in 1910.

Sources: Emperor of Japan: Meiji and His World, 1852-1912, Donald Keene, Columbia University Press, 200, p. 502-510; The Sino-Japanese War of 1894-1895: Perceptions, Power, and Primacy, S. C. M. Paine, Cambridge University Press, 2003, p. 287-293.

Before the ink was dry on the Treaty, Russia, Germany and France "suggested" to Japan that they had taken too much, were destabilizing East Asia, and should give up the Liaotung Peninsula (see above map) in exchange for an additional indemnity. This intervention, known as the Tripartite Intervention, backed by the veiled threat of military action and the possibility of losing all territorial gains, led to Japanese acquiescence (justified by the government as a "magnanimous gesture") and public and press outrage at the government's impairment of the "national honor and dignity."

Subjugation of Taiwan

The Taiwanese were not eager for their island to become a Japanese possession and several thousand irregulars, termed "bandits" by the Japanese, put up stiff resistance for almost five months (May 21 - October 21, 1895.) While only 396 Japanese were killed in action, over 10,000 succumbed to tropical diseases, including Prince Yoshihisa. The securing of Taiwan as part of the Japanese empire served as a salve on the damaged national pride caused by the Tripartite Intervention.Literature

Conflicts of Interest: Art and War in Modern Japan, Philip K. Hu, et. al., Saint Louis Museum of Art, 2016

In Battle's Light: Woodblock Prints of Japan's Early Modern Wars, Elizabeth de Sabato Swinton, Worcester Art Museum, 1991.

"New Wine in Old Casks: Sino-Japanese andRusso-Japanese War Prints," Elizabeth de Sabato Swinton, article in Asian Art Volume VI, Number 1, Winter1993, Oxford University Press.

The Sino-JapaneseWar, Nathan Chaikin, self-published, 1983

last revision:

6/11/2020

11/10/2018