Prints in Collection

| The Arraignment of Oyama Tsunayoshi, 1877 IHL Cat. #445 | Kagoshima senki, 1877 IHL Cat. #449 | Illustration of the Rebels Being Suppressed at Kagoshima, 1877 IHL Cat. #450 |

| Mr. Saigo's Amazing Charm to Ward Off Cholera, 1877 IHL Cat. #777 |

Mirror of Portraits of All Sovereigns in the World, 1879 IHL Cat. #2467 |

IHL Cat. #383

Sino-Japanese War Chronicle, 1895

IHL Cat. #158

Taiwan War: Illustration of the Battle

of Baguashan, 1896

IHL Cat. #1802

A Lady in Waiting Hands The Noh Mask

to an Actor

from the series Chiyoda Inner Palace, 1895

IHL Cat. #322After the Bath

from the series Chiyoda Inner Palace, 1895

IHL Cat. #302

Reading from the series Edo Brocades, 1902

IHL Cat. #355

Biographical Data

Profile

Yōshū Chikanobu 楊洲周延 (1838-1912)

Yōshū Chikanobu was a leading artist1 of the Meiji period (1868-1912), a time when Japan saw the reinstatement of the emperor as ruler and was undergoing rapid westernization. He was one of the most prolific woodblock print artists of this period, working with both traditional subjects, such as actors, courtesans, scenes of famous sites, beautiful women, and with topical subjects, such as the Satsuma Rebellion (1877) and the Sino-Japanese War (1894-1895.)2 Chikanobu used the flat planes and decorative patterning of the ukiyo-e tradition to striking effect, adding brilliant colors, especially reds, purples, and blues to his compositions. He worked in a style that often reflected western conventions in art. 1 Along with Yoshitoshi Tsukioka (1839-1892), Kobayashi Kiyochika (1847-1915) and Toyohara Kunichika (1835–1900).

2 There is speculation that due to the weak composition and effect in some of the Sino-Japanese War prints attributed to Chikanobu that a number of them may have been produced by his students rather than by the artist himself.

Artist Names

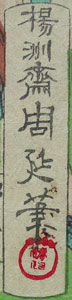

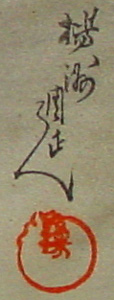

In addition to Yōshū Chikanobu (楊洲周延) he used the artist names (gō) Ikkakusai (一鶴斎), Yōshūsai (楊洲斎), Hashimoto Chikanobu (橋本周延) and Toyohara Chikanobu(豊原周延).Biography

Source: Chikanobu: Modernity and Nostalgia in Japanese Prints, Bruce A. Coats, Hotei Publishing, 2006Little is known about Chikanobu’s early life. Born in Niigata Prefecture as Hashimoto Naoyoshi (橋本直義), he was the eldest of two children. His father was Hashimoto Naohiro (died 1879) who was a lower level retainer of the Sakakibara daimyo. As a youth Chikanobu trained in the martial arts and in the late 1860s fought in the Boshin Civil War (1868-1869) with the Shōgitai, supporting the Tokugawa shogun’s military government against those seeking to install a modern government under the auspices of the emperor. In 1868, he was captured during the fighting, but was let go when it was confirmed he was a well-known artist.

As a child, he showed a talent for painting and he trained in a private studio teaching Kano School painting. He first studied print design with disciples of Keisai Eisen (1790-1848) and then around 1852, at the age of fourteen or fifteen, with Ichiyusai Kuniyoshi (1797-1861). During his time at Kuniyoshi’s studio Chikanobu may have known Yoshitoshi Tsukioka (1839-1892), who joined the studio in 1850. In about 1855 or 1856, Chikanobu moved to the studio of Utagawa Kunisada I (1786–1865). Coats states that Chikanobu’s earliest works were influenced by Kunisada’s style, “but he moves away from the Kunisada figural models by the 1880s. Over time Chikanobu’s women become taller, thinner and more graceful in their gestures, establishing a new canon of beauty for the mid-Meiji period that reflected a revival of interest in prints of a hundred years earlier.”1

In about 1862, Chikanobu began working with Toyohara Kunichika (1835–1900) studying actor portraiture, which Kunichika, his contemporary, was famous for. Later on Chikanobu and Kunichika would compete in designing actor prints for the same kabuki plays, but Chikanobu would go on to an expanded range of subject matter.

In 1871 Chikanobu established himself in Tokyo as a woodblock print artist, designing prints of familiar subjects such as the Yoshiwara pleasure quarters, scenic views and actor prints. In tracing the evolution of Chikanobu's actor prints, Coats writes, “…he moved away from the Utagawa school models he had been taught by Kunisada and Kunichika. Chikanobu’s actor prints changed from being posters in the 1870-80s, like others produced in the Utagawa school tradition, to compositions in the late 1890s that are individual works distinctly in his own style.”

In the mid-1870s, Chikanobu, like many other artists, designed kaika-e, prints that documented Japan's modernization and the Emperor Meiji and the imperial court's promotion of that modernization.

In 1877, Chikanobu would document, in over 45 triptych prints, the events around the Satsuma Rebellion, a short-lived samurai insurrection, led by Saigo Takamori (1827-1877).

In 1884, Chikanobu created at least ten triptychs on the attempted assassination of Japan's representative in Korea, Hababusa Yoshitada and the burning of the Japanese legation. These prints, issued very shortly after the incident, brought him "enormous success."2

By the late 1880s he and much of his audience were becoming dismayed by the rapid changes taking place in Tokyo and were increasingly nostalgic about the lost world of the shogun. Throughout the 1890s, Chikanobu produced single sheet prints, diptychs and triptychs, which promoted traditional values and highlighted aspects of Japanese culture that were being forgotten. He created prints about filial piety and neighborhood festivals to provide an alternative to what many saw as the deterioration of Japanese society caused by imported ideas and modern methods. Chikanobu's last works in the early years of the 20th century featured brave samurai and heroic women of Japan's past, models of appropriate behavior for the future. By 1905, his print production had dwindled.

Chikanobu died at the age of seventy-five from stomach cancer in 1912.

1 Chikanobu: Modernity and Nostalgia in Japanese Prints, Bruce A. Coats, Hotei Publishing, 2006, p. 16.

2 The Sino-JapaneseWar, Nathan Chaikin, self-published, 1983, p. 34.

Signatures

The following are representative signatures from this collection. For additional signatures see the website http://www.chikanobu.com/signature.asp |  |  1877 |  |  |

|  |  |

Print Series

Chiyoda Inner Palace (Chiyoda no Ooku)1895-1896

Chikanobu's series of forty prints depicting the lives of the ladies of the Chiyoda Inner Palace is considered by many his masterpiece. For additional details on this series, see the following print pages:

A List of Major Print Series

Source: Wikipedia http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Toyohara_ChikanobuSeries in the ōban yoko-e (landscape) format, which were usually then folded cross-wise to produce an album:

| Date | # Prints | Title |

| 1880 | 12 | Twelve Months at Home with the Royal Ladies kanke jūni kagetsu no uchi (冠化十二ヶ月の内) |

| 12 | The Education of Beautiful Women in Edo throughout the Whole Year kyōiku azuma bijin jūni kagetsu zen (教育東美人會十二ヶ月全) | |

| 1898 | The Tale of the Heike heike monogatari (平家物語) | |

| 1901 | 15 | An Annal of Eastern Pastimes azuma fūzoku mokuroku (東風俗目録) |

| 1903-1905 | 30 | Edo Brocade edo nishiki (江戸錦) |

| 1905 | Childhood Flowers yōchi hana (幼稚) | |

| 1906 | 4 | Educational Pictorial Album of History kyōiku rekishi gafu (教育歴史画布) |

At least one series was published in chuban yoko-e format:

| Date | # Prints | Title |

| 1882 | An Instruction Manual Depicting the Two Heads of Good and Evil zen'naku ryōtō kyōkun kagami (善悪両頭教訓鑑 |

and there is one series, attributed to Chikanobu, in chuban tate-e format:

| Date | # Prints | Title |

| probably a hikifuda (advertising circular) for cloth/clothing, published by Tōkyō hatsubaimoto (Tokyo sales agency) miyako no hana iro (都の花色) |

In addition there is at least one harimaze-e series in yatsugiri format:

| Date | # Prints | Title |

| 1879 | Contrasting the Flowers of Tokyo Tōkyō hana kurabe (東京花竸) |

as well as one harimaze-e series in koban yoko-e format:

| Date | # Prints | Title |

| 1882 | A Mirror of Valor in our Country honcho buyū kagame (本朝武勇鑑) |

A partial list of his single panel ōban tate-e series includes:

Two of his well-known ōban tate-e diptych series are:

| Date | # Prints | Title |

| 1893 | Very Tall Stories about Famous Women of Japan nihon meijo to (日本名女吐) | |

| 1897-1898 | An Exposition of Beautiful Women in Scenic Places meisho bijin kai (名所美人合) |

This is only a partial list of his triptych series:

| Date | # Prints | Title |

| 1885 | Sands of Edo - Annual Events Edo sunago nenjū gyōji (江戸砂子年中行事) | |

| 1885 | Scenes from a Chrysanthemum Festival Chōyō no zu (重陽之圗) | |

| 1887 | Scenes of Various Women's Ceremonies Fujin shoreshiki no zu (婦人諸禮式の図) | |

| 1889 | Daily Life in Edo Throughout Twelve Months edo fūzoku jūni kagetsu no uchi (江戸風俗十二ヶ月の内) | |

| 1889 | Looking into the Past: The Pride of the East onko azuma no hana (温故東の花) | |

| 1892 | A Collection of West Country Elegance saigoku ga shū (西国雅集) | |

| 1892 | Three Famous views of Japan nihon sankei no zu (日本三景の内) | |

| 1892 | Customs of Old Japan yamato fūzoku (倭風俗 | |

| 1894-1896 | 40 | Court ladies of Chiyoda Palace (The Imperial Ladies' Quarters at Chiyoda Palace or The Customs of the Inner Palace of the Chiyoda Castle) chiyoda no o-oku (千代田の大奥) |

| 1896 | Ladies of the Tokugawa period Tokugawa jidai kifujin (徳川時代貴婦人) | |

| 1898 | Chiyoda Palace: Outside the Walls chiyoda no on-omote (千代田の御表 | |

| 1898 | Handbook of Ladies' Etiquette joreishiki ryaku zu (女禮式略の図) | |

| 1898 | Then and Now ima to mukashi (今とむかし) | |

| 1898 | Verses of the Middle Rank take no hitofushi (竹乃一節) | |

| 1884 | A Report of the Korean Disturbance chōsenhen hō (朝鮮變報) | |

| Inside Snow, Moon, Flower settsu gekka no uchi (雪月花の内) | ||

| Complete Lessons of Japanese History nihon reikishi kyōkun jin (日本歴史教訓尽) |

Recent Exhibitions 2007-2008

Chikanobu: Modernity and Nostalgia in Japanese Prints

Source:http://collegerelations.vassar.edu/2007/2358/ and http://www.denison.edu/campuslife/museum/chikanobu.htmlThisexhibition, composed of nearly 60 prints produced during the Meiji period(1868-1912), explores the 30-year career of the popular woodblock designer Yoshu Chikanobu. The exhibition was organized by Bruce A. Coats, a Professor of Art History and the Humanities at Scripps College, in conjunction with colleagues at several liberal arts colleges in the United States. Funded by the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, the exhibition opened in August at Scripps College, followed by showings at Carleton College, Vassar, Denison University, Boston University, DePauw University, and the International Christian University in Tokyo. An extensive catalogue by curator Bruce Coats shares the exhibition's name, and features additional essays by Allen Hockley, Kyoko Kurita, and Joshua S. Mostow (Hotei Publishing).

"The Obiturary of Yōshū Chikanobu" Miyako Shinbun (Capital City Newspaper), October 2, 1912

trans. by Kyoko Iriye Selden, Senior Lecturer, Department of Asian Studies, Cornell University, ret'd.Yōshū Chikanobu, who represented in nishiki-e the Great Interior of the Chiyoda Castle and was famous as a master of bijin-ga, had retired to Shimo-Ōsaki at the foot of Goten-yama five years ago and led an elegant life away from the world, but suffered from stomach cancer starting this past June, and finally died on the night of September 28th at the age of seventy-five.

His real name being Hashimoto Naoyoshi, he was a retainer of the Sakakibara family of Takata domain in Echigo province. After the collapse of the Tokugawa Shogunate, he joined the Shōgitai and fought in the Battle of Ueno. Thereafter he fled to Hakodate, fought in the Battle of the Goryōkaku under the leadership of Enomoto Takeaki and Ōshima Keisuke, and achieved fame for his bravery. But following the Shōgitai’s surrender, he was handed over to the Takata domain. In the eighth year of Meiji, with the intention of making a living in the way that he was fond of, went to the capital and lived in Yushima-Tenjin town. He became an artist for the Kaishin Shinbun12, and on the side, produced many nishikie pieces. Regarding his artistic background: when he was younger he studied the Kanō school of painting, but later switched to ukiyo-e and studied with a disciple of Keisai Eizen; and next joining the school of Ichiyūsai Kuniyoshi, called himself Yoshitsuru. After Kuniyoshi’s death, he studied with Kunisada. Later he studied nigao-e with Toyohara Kunichika, and called himself Isshunsai Chikanobu. He also referred to himself as Yōshū.

Among his disciples were Yōsai Nobukazu (楊斎 延一), Gyokuei (楊堂玉英)(Yōdō Gyokuei as a uchiwa-e painter), and several others. Gyokuei produced Kajita Hanko. Since only Nobukazu now is in good health, there is no one to succeed to Chikanobu’s bijin-ga, and thus Edo-e, after the death of Kunichika, has perished with Chikanobu. It is most regrettable.

1 the party organ of the Rikken Kaishinto, the Constitutional Reform Party.

last revision:

last revision:

1/6/2019