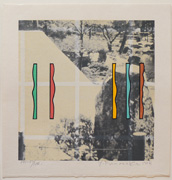

| IHL Cat. #1096 and #1097 |

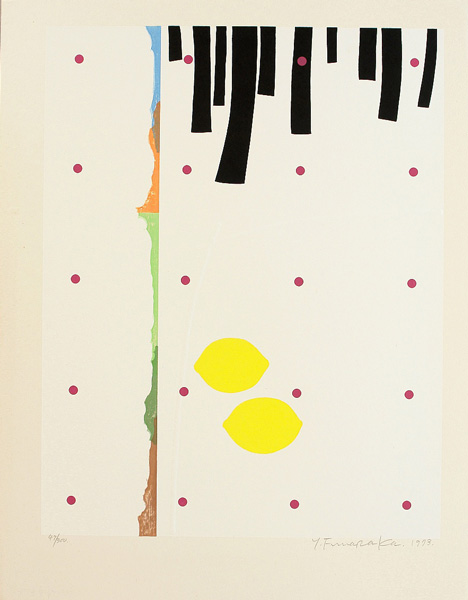

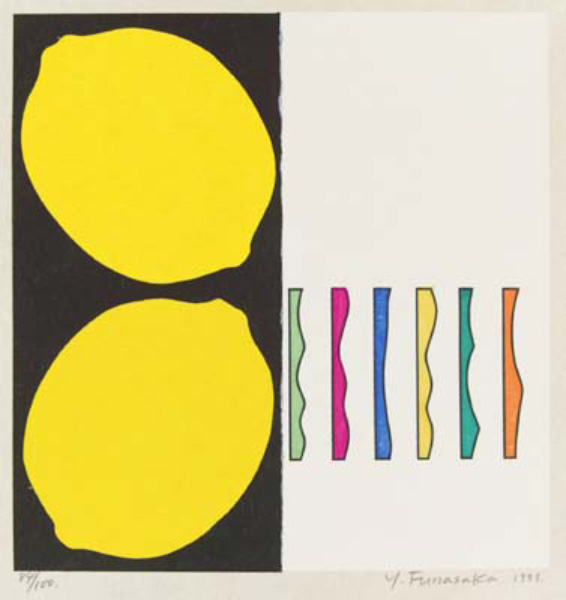

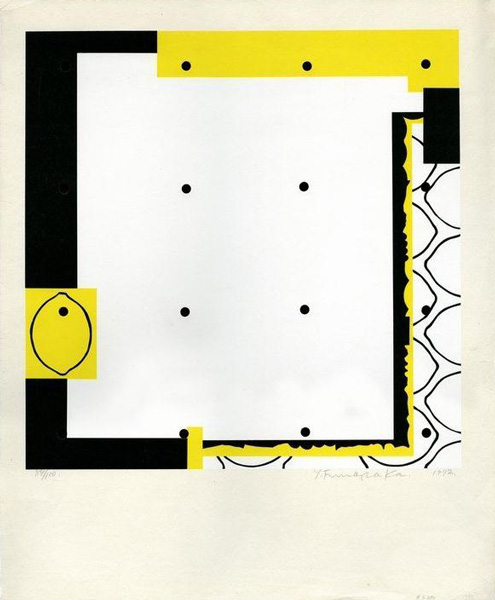

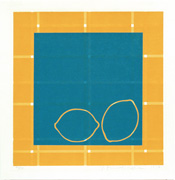

IHL Cat. #1579 | Lemon, 347, 1973 IHL Cat. #1078 | Blue and White space, No. 366, 1974 IHL Cat. #808 |

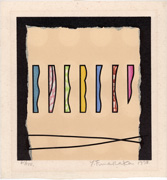

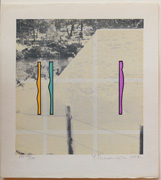

| IHL Cat. #1077 |  Mt. Fuji, No. 480, 1976 IHL Cat. #891 | My Space and My Dimension, No. 515, 1977 IHL Cat. #1335 |

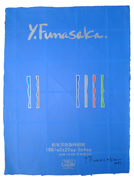

Y. Funasaka., Parco Gallery One Man Print Show (Exhibition Poster), 1981 IHL Cat. #1679 |

| IHL Cat. #1573 | IHL Cat. #987 | IHL Cat. #1049 |

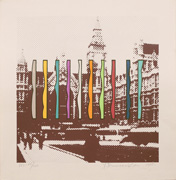

IHL Cat. #985 | 883 (British Parliament), 1885 IHL Cat. #1056 | IHL Cat. #1165 |

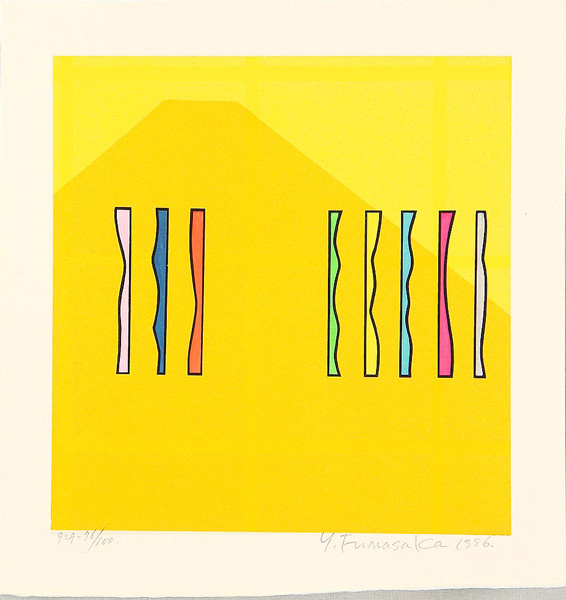

| My Space and My Dimension Prints by Yoshisuke Funasaka at Gallery Nakama (Exhibition Poster), 1986 IHL Cat. #1678 | 920, 1987 IHL Cat. #1166 |  IHL Cat. #986 IHL Cat. #986 |

| Lemon 2 (Yellow, Black, White), c. 2000 IHL Cat. #1312 | Lemon 5 (Yellow, Black, White), c. 2000 IHL Cat. #1314 | Lemon 12 (Yellow, Black, White), c. 2000 IHL Cat. #1313 |

| Lemon 17 (Yellow, Black, White), c. 2000 IHL Cat. #1341 |

Biographical Data

Biography

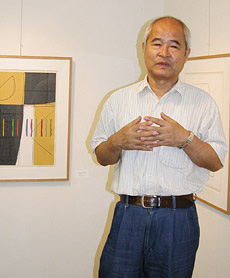

Funasaka was born in Gifu Prefecture in 1939, the son of the painter and watercolorist Funasaka Masayoshi. He graduated in 1962 from the Oil Painting Department of Tama Art University, Tokyo. While a student, Funasaka worked part-time in a linoleum store and used linoleum trimmings to make linocut prints.1 He became a Japan Print Association member in 1960 and remains a member.

Funasaka's first solo show was held in 1967 and he began showing internationally soon thereafter, winning a prize in 1970 at the Tokyo International Print Biennale. In 1976 he was awarded a fellowship by the Japanese Government Oversea Training Program for Artists and studied in the the United Sates and London for two years. He has taught printmaking since 1974, when he began teaching printmaking at the Asahi Culture Center, and has been instrumental in bringing foreign artists to Japan to learn traditional Japanese arts. Since 1979, he has exhibited regularly with the College Women's Association of Japan print show.

Recurring Objects - Lemons, Holes and Vertical Marks

Funasaka's work, which encompasses well over a thousand prints, is most recognizable by the recurring use of three objects - the lemon, the hole and a unique vertical mark created by the artist. His work is almost universally abstract, even when incorporating the lemon.

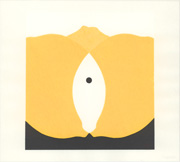

The artist has used the shape of the lemon since 1957 and it appears in groups, singly, as the outline of a breast, or as an element in an abstract composition. The familiar yellow oval, always normal in size, may contrast starkly with red-orange or black backgrounds or may almost disappear in a less dominant role.2

His lemon prints have been described as "both sensual and animated" and providing "deep meaning from the simplest of images."3 For Funasaka, the lemon is at first glance "quite simple" but growing more complex "the more you look at it."4 He likes its duality, soft but bitter and appearing smooth to the eyes, but rough to the touch, and its sensuality "when cut in the center, both halves are contoured like breasts."5 On an elemental level Funasaka states, "I like the taste, I like the smell, I like the color - it represents freshness."6

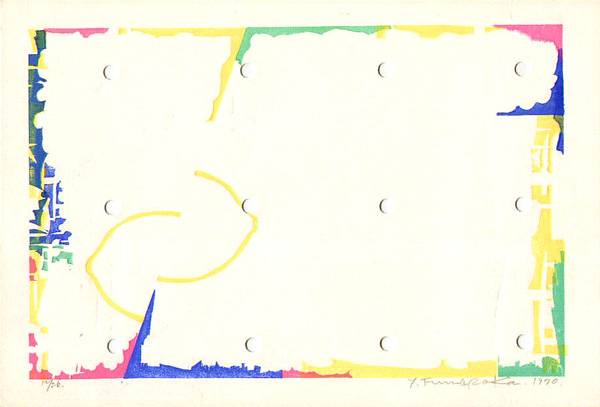

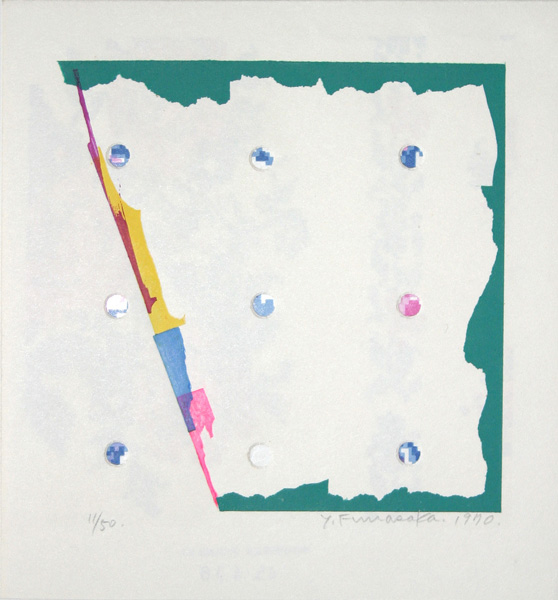

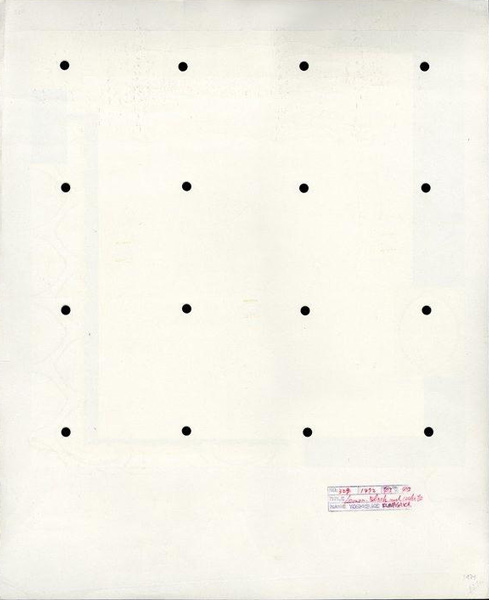

Funasaka's holes bring to his prints a third dimension that is often lost when seen on the web or in printed books. He makes his holes in various ways, including burning them through the paper with a cigarette.

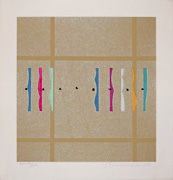

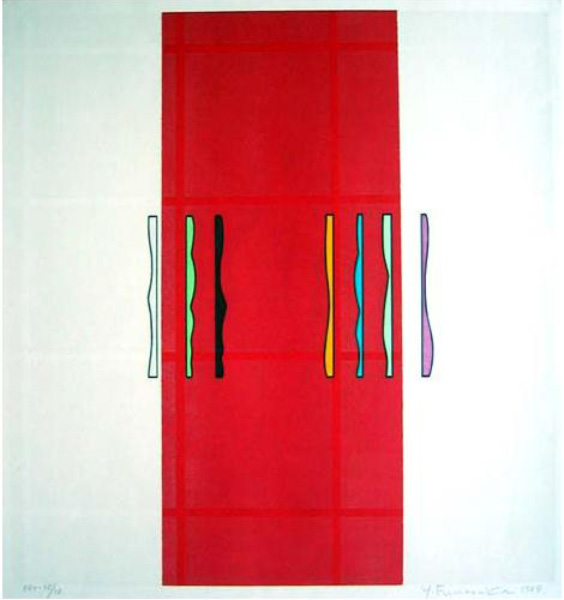

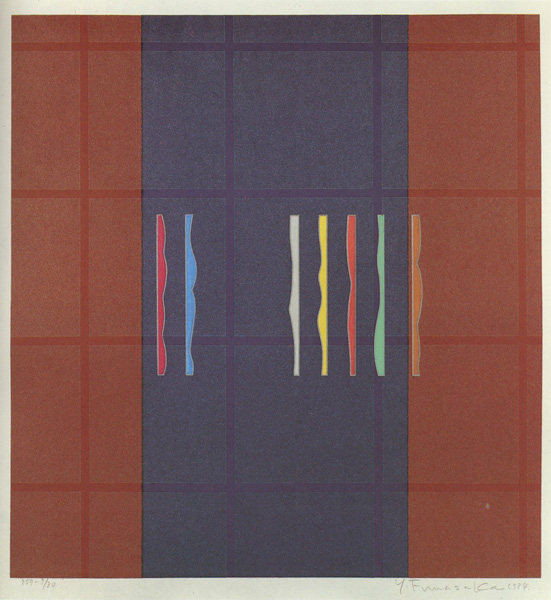

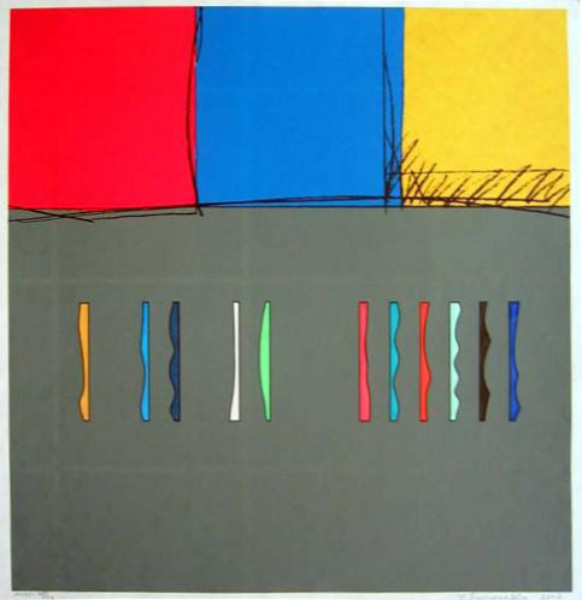

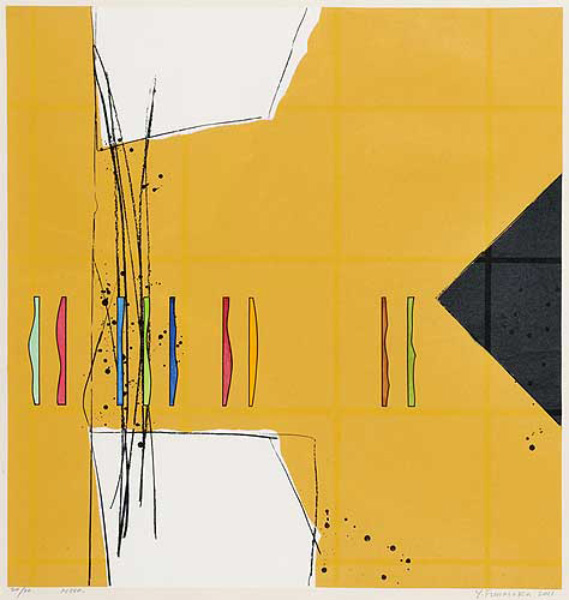

Funasaka has also made hundreds of prints using a unique vertical form that reappears with variations in color and background. These prints often carry the title "My Space and My Dimension." These shapes are printed by woodblock and the artist has "devised his own method of mounting them separately so that they can be rearranged without carving a complete block."7 In these prints, Funasaka may employ mica dust [in an emulsion with silkscreen ink], unmo, to achieve "exquisitely subtle contrasts in surfaces, reminiscent of the satin and matte patterns woven into kimono and obi silks," although the artist maintains that he is not consciously influenced by textile designs.8

| My Space and My Dimension - 857, 1984 | My Space and my Dimension - M395, 2002 | My Space and my Dimension - M880, 2011 |

Source: Japanese Prints Today: Tradition with Innovation, Margaret K. Johnson, Dale K. Hilton, Shufunotomo Co., Ltd., 1980, p. 60-63.

Woodblock is Funasaka's favorite medium. He enjoys all of its aspects; the carving, the inking, the baren-rubbing, and the printing. His earlier works were created totally with woodblock processes but later work employed silkscreening, primarily for the backgrounds, and lithography.

A favorite tool for Funasaka is the baren, a tool he uses in the traditional way to rub the ink from the woodblock onto the paper. He treasures the craftsmanship of the old baren-makers who are fast disappearing. Consequently, Funasaka has learned to make his own barens. A fine baren may have fifty or more thin layers of paper glued together to make a disk upon which is placed a finely braided bamboo spiral. Over the bamboo spiral is stretched the broad skin of a bamboo shoot. The skin is twisted together on the back of the disk in the form of a handle for gripping. The artist teaches this craft as part of his woodblock courses.

Simplicity and Purity

In Collecting Modern Japanese Prints Then & Now, the Tolman's find "the appeal of his work lies not only in its crafted simplicity but also in its formal purity. He manages to balance the shapes to carve out his own private space and to create tension with these elements."9

By using similar groups of titles for his prints and, perhaps, just adding a serial number to differentiate titles, "he dissuades his viewers from looking for explicit meaning. Instead they can concentrate on his world of pure form, an austere and even restricted world of familiar shapes which reveals great subtleties on close scrutiny."10

In their book Japanese Prints Today, Tradition with Innovation, Johnson and Hilton comment:

[H]is prints breathe with spacial expansiveness - exciting in its simplicity. The quiet presence of the regularly placed circular forms lends interest without disturbing the simplicity. One senses serenity, yet an excitement for the space itself, not unlike that of a Japanese garden or a tea ceremony room, where small spaces have been made to appear large by careful placement of objects and textures. Here, too, serene but vibrant worlds are formed from limited spaces to provide refuge from the confusion and complication of the outside world.11

Recent Exhibitions and Collections

| Fukuoka Art Museum June 2010 Ma The Space Enlightened Yoshisuke Funasaka and Katsu Murakami | The artist has had numerous gallery shows in Japan over the past 3-5 years along with a major show at the Fukuoka Art Museum in June 2010 titled Ma The Space Enlightened - Yoshisuke Funasaka and Katsu Murakami in which the artist's drawings were highlighted. In 2003, an exhibition held in Tokyo and then Kalamazoo, Michigan, showcased the work of over 40 Japanese artists who were students of Funasaka's in addition to 21 American artists, some of whom also studied with him. Collections (a partial list): Tokyo National Museum of Modern Art; Kyoto National Museum of Modern Art; Tochigi Prefectural Art Museum; Chase Manhattan Bank, Tokyo; Cincinnati Art Museum; Bibliotheque Nationale, Paris; Art Gallery of New South Wales, Australia; British Museum, London; Freer Art Museum, Washington, D.C.; Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.; Art Institute of Chicago; Library of Congress - College Women's Association of Japan Print Show Collection; Brooklyn Museum; Moscow National Oriental Museum, Russia; Phoenix Art Museum; Bibliotheque Nationale, Paris |

Artist's Statement October 2014

Prints by resins and encouragement by John Ruskin - Funasaka Yoshisuke Japan has the tradition of making woodcuts, Ukiyo-e prints, from [the] Edo period.

Japanese students of elementary school and junior high school often make New Year Greetings by woodcuts in December. These situations inspired me to get interested in woodcuts from youth. In the third grade of junior high school, I submitted my work to [a] prints competition which was held by Asahi shimbun for elementary school and junior high school students and I got a prize. [As a result, I came] to know Muto Rokuro (1907-1995) who was a woodcut artist and one of the judges of this competition. Since that time he was my woodcuts mentor officially and privately until he passed away. In those days, Munakata Shiko (1903-1975) attracted interest internationally. It made me think that woodcuts would be interesting. Woodcuts by water print, which I pursued, would lead me to the success in the future, I thought. The reason I thought so was that the technique of waterprinting [I think Funasaka is referring to water-based, rather than oil-based inks] by “baren” was unusual. The feel of wood engraving, the skin of wood and warmth…. The colour printed by “baren” enables unique expressions which cannot be seen in other printing style. I think it was lucky to be able decide which way to go at that early age.

When I came to Tokyo to take the examination for an art university, one of Mr. Muto’s acquaintances told me to go to Watanabe Woodcuts Workshop if I intended to make a living by woodcuts. Watanabe Woodcuts Workshop, as a publisher of Ukiyo-e prints, had craftsmen who made works of Ito Shinsui (1898-1972) or Kawase Hasui (1883-1957), and manufactured “Shin-Hanga”, which were different from Ukyo-e prints. Watanabe Woodcuts Workshop held the group exhibition and the meeting for the study of woodcuts once a month on the second floor. They had meetings to exchange ideas on their works to enlighten and educate young artists on prints. Mr. Watanabe, the storekeeper, sponsored these meetings and many famous artists participated in them. The meeting continued until 1969 when the building was rebuilt. Mr. Ueno Makoto, one of the members of the meeting, inspired me to submit my work to the exhibition by The Japan Print Association. It was my first public exhibition. I got linoleum from my part-time job place for my works. [Funasaka is referring to his carving on linoleum for many of his early prints.]

When I was working on my works, I found a very important book at a second hand bookstore in Kanda. The book, “A Political Economy of Art”, was written by John Ruskin (1819-1900), a British economist. The book introduced his lectures at Oxford University. It deals with the evaluation of William Turner (1775-1851), a British landscape painter, the universality of the works, the timelessness of the materials, the nature of the artist, and the sensitivity of craftsmen. It has been not only one of my favourite books, but also the important support for my view on artistic activity since then.

From 1960s to 1970s, the prints artists had great enthusiasm and were thinking what prints were, or what they could do in the category of prints. I was searching for a new method of prints: not using wood boards, but using glue. My works in early stage were made in this method. I drew pictures on the glass. In this method, it was hard to work glass into various shapes, so I chose to make the plates from synthetic resins. The liquid resins were easy to spread on the glass. The hardening agents were needed to harden the resins, and the time for making the plates could be kept by controlling the amount of the agents. When the resins were soft, I could engrave them with knives or leave my hand print or the marks of other materials. After that, I spread the oil-based paint on the plate with rollers. The extra paint on the glass was wiped by wet cloth. And then, I put a piece of paper on the glass and printed it. After printing, the plate can be scraped off by the flat knife easily.

You can see lemon shape in the works in those days. One hot day in summer, I found some lemons on the counter in a cafe. While I was gazing at those lemons, I began to think that I could use the shape of lemons in my works as my special feature. I exhibited my lemon works when I had the first exhibition of my own works at Okura gallery in Ginza. Mr. Horiuchi Yoshio, who was the advisor of the gallery and a prints artist, introduced me [to] Mr. Sherman Lee, who was a Japanese art scholar and worked at the cultural section of Japan Times. I gave him an invitation. He kindly wrote the articles on almost all of my exhibitions held in Tokyo. Unfortunately, Japanese newspapers rarely wrote about my exhibition. However, many foreigners who saw the articles by Mr. Lee visited my exhibition. He always wrote about the shape of the lemons and commented on my works. I have been called “Funasaka: Lemon”. Some English books which wrote about my works often paid attention to the works of the lemons or the works with holes. In this way, my works got acknowledged and I decided to keep making woodcuts. The articles by Mr. Lee led me to hold the exhibition in Los Angeles. After that, I kept publishing new works.

In 1970, I got a prize at the 7th International Biennial Exhibition of Prints in Tokyo, and it was the turning point of my life as a prints artist. One or two days after the judgement, the Head Judge, Mr. Peter Bird and his wife, Mrs. Birgit Skiold from the United Kingdom visited me suddenly. He was a director of an art museum in the U.K., and Mrs. Skiold ran a prints workshop in London and worked as a prints artist. In those days, she was working on the works by the etching, which were white, blind printing, uneven and wave-like. Since I was also making such kind of works at that time, they might have got interested in my works. It was great pleasure. They encouraged me to come to the U.K. and I didn’t hesitate in deciding to go there. The United Kingdom, the country of William Tuner, who was evaluated by John Ruskin. It led me to apply to the overseas training by the Agency for Cultural Affairs. In 1976, when I spent about 8 months in London, I visited [the] Tate Gallery for many times. The works by Turner were derisive [sic] and dynamic with light, air, and arising steam. During my stay in London, I had chances to hold exhibitions at 3 galleries. In addition, having workshop or demonstrations there made my training in London very meaningful. My second place for training was Western Michigan University in the United States. Mrs. Skiold introduced me Prof. Richard de Paux. At the university, I often had demonstrations and workshops. Mrs. Skiold gave me chances to hold exhibitions or get companionship with the artists in the world and widened my activity as an artist. Mr. Peter Bird and Mrs. Birgit Skiold passed away 7 or 8 years ago.

Mr. Suematsu Masaki (1908-1966) is also one of the most important people in my artistic activity. He was a teacher in charge when I was in the third grade of Tama Art University. After the Second World War, he came back from France and promptly introduced the contemporary art in France or the abstract paintings of Salon de Mai. He associated with Andre Breton (1896-1966), a French poet and a critic, and made some abstract paintings. I was affected by his works.

It is so hard to print on wide space by wood engraving that I had the wide blank space printed by silk screen. I print the one colour works or the many colours on one wood board works by myself. You can see the transparent objects which are circle or checkers in the works. I use mica in the solvent [to keep] the colours from fading. Mica reflects the light a little.

1 Images of a Changing World: Japanese Prints of the Twentieth Century, Donald Jenkins, Portland Art Museum, 1983, p. 147.

2 Who's Who in Modern Japanese Prints, Frances Blakemore, Weatherhill, 1975, p. 37.

3 website of Walsh Gallery http://www.walshgallery.com/contemporary-japanese-art-2002/

4 Ibid.

5 44 Modern Japanese Print Artists, Gaston Petit, Kodansha International Ltd., 1973, p. 104-105.

6 Op. cit, Blakemore.

7 Contemporary Japanese Prints: Symbols of a Society in Transition, Lawrence Smith, Harper & Row Publishers, 1985, p. 28.

9 Japanese Prints Today: Tradition with Innovation, Margaret K. Johnson, Dale K. Hilton, Shufunotomo Co., Ltd., 1980, p. 61.

10 Op. cit., Lawrence Smith. In regards to the artist's print titles, they often appear on the print's verso in the form of a stamped or pasted label with the artist's name and the prints "No." date of printing, size and title hand written.

11 Op, cit. Japanese Prints Today: Tradition with Innovation, p. 63.

i-39aa994048dc8c9c.jpg)