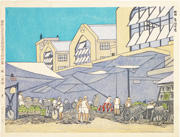

Falling Star Pine Tree at Zenyoji Temple #64 from the series One Hundred Pictures of Great Tokyo in the Showa Era, 1935 IHL Cat. #99 | IHL Cat. #974 | |

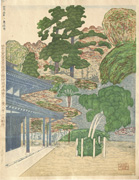

Shower at Nezu Shrine #81 from the series One Hundred Pictures of Great Tokyo in the Showa Era, 1936 IHL Cat. #975 |

Biography

Koizumi Kishio 小泉癸巳男 [こいずみ きしお] (1893-1945)Source: British Museum website http://www.britishmuseum.org/research/search_the_collection_database/term_details.aspx?bioId=146500

Print artist Koizumi Kishio was born in Shizuoka. He was the son of a specialist in calligraphy who commissioned woodblock-printed manuals and he learned the craft from his father's block-carver Horigoe Kan'ichi. In common with many sosaku hanga (creative print) artists he studied Western-style water-colour, in his case under Ishii Hakutei (1882-1958) and Maruyama Banka (1867-1942), at the Nihon Suisaiga-kai (Japan Watercolour Institute) in Tokyo. The three founders of the Institute [Ishii Hakutei (1882-1958), Tobari Kogan (1882-1927) and Nakazawa Hiromitsu (1874-1964)] were also woodblock printmakers and Koizumi was naturally led along that path, especially by Tobari Kogan, whom he knew as a colleague in carving blocks for newspaper illustration. He was an early member of the Creative Print Association from 1919 and an activist in it and its successors. Like Tobari he was a practical carver of blocks and like him wrote a practical manual much used by other artists, Mokuhanga nohorikata to surikata (The method of carving and printing woodblockprints, 1924).1 He is best known for his series Showa dai Tokyohyakkei zue (One Hundred Views of Great Tokyo in the Showa Era) whichhe produced himself between 1928 and 1940. Although artistically interesting only in parts, the series is a detailed and nostalgic survey of pre-war Tokyo, including a poignant view of Frank Lloyd Wright's old Imperial Hotel. Koizumi was influential on the sosaku hanga movement through his manual and through carving and printing for other artists. He was forced to leave Tokyo by the Pacific War, and died in Saitama in 1945 before he could return.

1 According to Helen Merrit in Modern Japanese Woodblock Prints - The Early Years,University of Hawaii Press, 1998, Koizumi was encouraged by Yamamoto Kanae (1882-1946), considered the founder of the sosaku hanga movement, who was anxious to spread knowledge of how to make hanga, to write Mokuhan no horikata-surikata.

The Series - One Hundred Pictures of Great Tokyo During Showa (Showa dai Tokyo hyakuzue)

Koizumi's most ambitious project was a series entitled Showa dai Tokyo hyakuzue (One Hundred Pictures of Great Tokyo During Showa) which he designed and carved. He began this series in 1928 and completed it twelve years later in 1940. In the series Koizumi documented the architectural styles and cityscapes of the times- the new Diet building, art deco structures on business streets,industrial sites, and traditional temples.

Koziumi was an accurate recorder of the scenes around him. His hundred pictures of Tokyo are a valuable historical record of the architecture and life of the city, doubly valuable today because so much of the city he knew is no longer there.

Source: Beyond the Great Wave: The Japanese Landscape Print, 1727-1960, James King, Peter Lang AC, International Academic Publishers, 2010, p. 179-180.

"From 1929 to 1937, Koizumi was preoccupied with his Tokyo series. The growing militarism of Japan in the thirties can be clearly seen in the several images in which soldiers stand guard outside buildings or one in which they take target practice at a range in Toyama... Several prints show the new buildings that have been erected since the earthquake [Great Kanto Earthquake of 1923], and there are colour-filled views of various public parks in Tokyo. Yet urban angst also is suggested...

...[T]hese prints may have been intended not so much as social commentary but as a gesture on the artist's part toward inclusivity. Ultimately, that is exactly what Koizumi accomplishes - using a wide variety of methods ranging from realism to quasi-surrealism, he shows a city resurrected from a great natural calamity. In accomplishing that aim, Koizumi encapsulates poverty, growing militarism, and urban malaise. Physically, the city has recovered, he suggests, but that does not mean that its psychic health has been renewed."

The Publisher of the Series

Most sources, including the definitive work on this series1, credit the carving, printing and publishing of this series to the artist. However, Merritt, in Modern Japanese Woodblock Prints, makes two references to Asahi Press as the publisher of some or all of the prints.2 The Carnegie Museum of Art also credits Asahi Press as the publisher of the seven prints from this series in their collection.

1 Tokyo: The Imperial Capital Woodblock Prints by Koizumi Kishio,1928-1940, Marianne Lamonaca, The Wolfsonian-Florida International University, 2004.

2 According to Merritt on p. 74, "some new prints published by Asahi Press were substituted in 1940." On p. 249 in "Notes on Selected Prints and Series" she writes, in referencing the entire series "Carved and printed by the artist; published by Asahi Press."

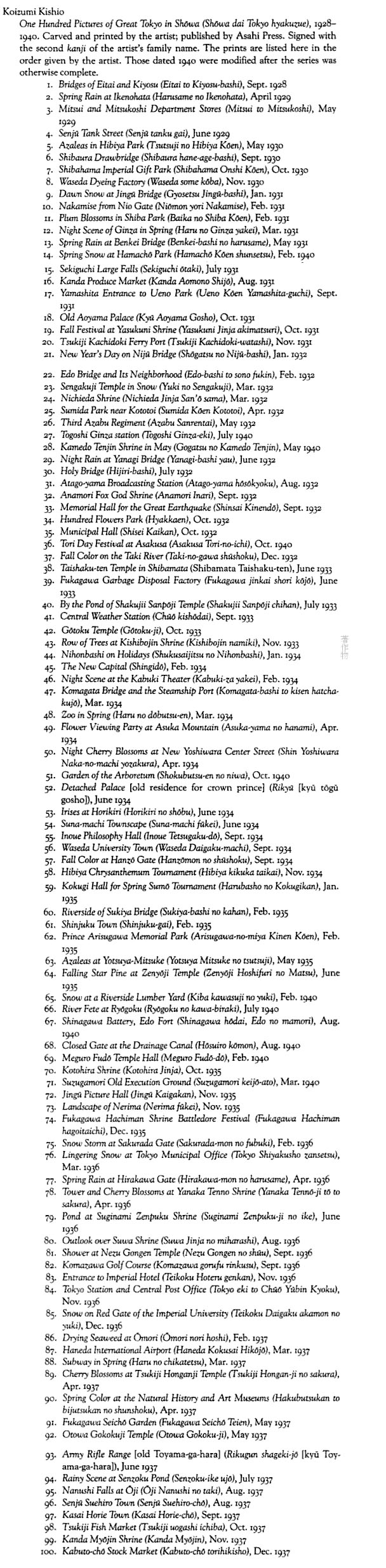

List of prints

Source: Guide to Modern Japanese Woodblock Prints: 1900-1975, Helen Merritt and Nanako Yamada. University of Hawaii, 1992, p. 249-252

Recent Exhibitions

"Tokyo in Transition" - Tokyo Edo Museum 1996

In 1996 the Tokyo Edo Museum held an exhibition Tokyo in Transition, showing Koizumi prints and other Tokyo-related series from the 1920s and 1930s.These prints have become an important document of urban development."Tokyo: The Imperial Capital: Woodblock Prints by KoizumiKishio, 1928-1940" - Wolfsonian-Florida International University 2003

In 2003, Florida International University's Wolfsonian Museum held the exhibition Tokyo: The Imperial Capital: Woodblock prints by Koizumi Kishio, 1928-1940 which showed selected prints form his series One Hundred Pictures of Great Tokyo in the Showa Era (Showa dai Tokyo hyakuzue).TOKYO: THE IMPERIAL CAPITAL: WOODBLOCK PRINTS BY KOIZUMI KISHIO, 1928-1940

Wolfsonian-Florida International University Exhibition

November 21, 2003–May 2, 2004

Introduction

At 11:58 a.m. on 1 September 1923 an earthquake struck Tokyo and eastern Japan with devastating force. A vigorous rebuilding campaign restored the city and transformed it into Japan's imperial capital, despite the rigors of economic depression both locally and abroad.

One of the woodblock-print artists who captured the drama of its rebirth was Koizumi Kishio (1893–1945), who created One Hundred Pictures of Great Tokyo in the Showa Era (Showa dai Tokyo hyakuzue) from 1928 to 1940. The Wolfsonian's portfolio of Koizumi's prints depicts the transformation of a key Asian city as it embraced modernity, maintained traditions, and became the backdrop for the militaristic ambitions of empire.

A Biographical Note

Koizumi Kishio was born in 1893 in Shizuoka, on Japan's southern coast. His father, a master calligrapher, recognized his son's talent for drawing and encouraged him to pursue a career as an artist, or more literally in Japanese, one who draws pictures (e-kaki). During this period, an artist could make a reasonable living as an illustrator or as a designer for textiles, ceramics, and lacquer wares.

Koizumi moved to Tokyo in 1909 or 1910, where he enrolled in the Japan Watercolor Academy (Nihon Suisaiga Kenkyusho), founded in 1907 by artists interested in the artistic culture of the West. The school was at the heart of the new printmaking movement in Japan, in which artists single-handedly conceived and produced their own prints.

Koizumi exhibited with the emerging organizations that accepted the new style of printmaking and was among the first members of the Nihon Sosaku-Hanga Kyokai (Japanese Guild of Creative Printmakers). In 1920 he produced a twelve-print series of Tokyo that depicted mainly nostalgic views of the old eastern part of the city around Asakusa. Between 1928 and 1937 Koizumi produced One Hundred Pictures of Great Tokyo in the Showa Era (Showa dai Tokyo hyakuzue). In the late 1930s, despite declining health, he began work on thirty-six views of Mount Fuji. At the time of his death on 7 December 1945 he had completed work on twenty-three of the Mount Fuji prints. In the following year, they were exhibited at the Mitsukoshi Department Store in Tokyo.

One Hundred Pictures of Great Tokyo in the Showa Era

One Hundred Pictures of Great Tokyo in the Showa Era (Showa dai Tokyo hyakuzue), by Koizumi Kishio, provides contemporary audiences with an opportunity to explore the rebirth of Tokyo in the years following the Great Kanto earthquake of 1923.

Since the thirteenth century, the organizing principle of "one hundred" had been used to canonize auspicious themes in Japanese poetry (and later in art). In printmaking this form reached its peak in the first half of the nineteenth century. Koizumi's personal list of one hundred sites in the newly rebuilt Tokyo mixed popular choices with selections that are obscure and arcane. His highly personalized interpretations of the city and depictions of settings that carried great meaning for him are a pantheon of important views—from modern facilities such as Haneda Airport to nostalgic renderings of revered ancient temples. Koizumi's role as a nominator of new places, and as a subtle provocateur who presented politically charged suggestions in a highly traditional format, may be seen as a unique contribution to the Japanese printmaking genre.

Press Release for the Exhibition

Source: website of Florida International University's Wolfsonian Museum http://www.wolfsonian.org/visitus/press/06.26.03.html

TOKYO: THE IMPERIAL CAPITAL OPENS NOVEMBER 21, 2003 AT THE WOLFSONIAN–FLORIDA INTERNATIONAL UNIVERSITY IN MIAMI BEACH; A SELECTION OF WOODBLOCK PRINTS FROM A PORTFOLIO BY KISHIO KOIZUMI REVEALS TRANSFORMATION OF A CITY

On September 1, 1923, at 11:58 a.m., an earthquake struck eastern Japan with devastating force. Tokyo suffered vast damage and loss of life. Attempts to reconstruct the metropolis were complicated by domestic and international economic depression in the late 1920s. Ultimately, however, a vigorous rebuilding program, particularly robust during the 1930s, virtually transformed the city's face and patterns of life.

This fall, The Wolfsonian–Florida International University will present Tokyo: The Imperial Capital, an exhibition of woodblock prints by Japanese artist Kishio Koizumi (1893-1945). The exhibition will run from November 21, 2003 to May 2, 2004. Koizumi captured the drama of the rebirth of the imperial Japanese capital in the portfolio One Hundred Pictures of Great Tokyo in the Showa Era (Showa dai Tokyo hyakuzue), produced in installments from 1928 to 1940. The Wolfsonian's Koizumi prints form the core of an exhibition that will examine the shape and texture of a great Asian city as it manifested the modern, searched for stability in tradition, and became the site of ultimately disastrous political policies.

For most of the twentieth century Tokyo has embodied dramatic transformations. Soon after Koizumi documented the post-earthquake renewal, Tokyo was again reshaped following the Second World War. These images provide a snapshot of a city striving toward imperial splendor.

"Only in recent years have social and art historians begun to carefully study the art produced in Japan during the sixty or so years of extraordinary social change between the 'reopening' to interaction with the world in the 1860s and the debacle of the Pacific war. Within this huge body of visual material are fascinating indicators and clues about larger cultural and political shifts," comments James T. Ulak, the chief curator of the Freer Gallery of Art and the Arthur M. Sackler Gallery of the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C., who co-curated the show with The Wolfsonian's assistant director for exhibitions and curatorial affairs, Marianne Lamonaca. Ulak also serves as head of the collections and research division for the Freer and Sackler.

"Kishio Koizumi used as his framework the well-known nineteenth-century print series The Hundred Views of Edo by Hiroshige," Lamonaca explains. "But in this case he records the period following the Great Earthquake of 1923, when Tokyo was being rebuilt according to Westernized ideas about what a modern, international city should be."

Through these prints he embraces the modern spirit of the times but also maintains certain aspects of traditional Japanese culture, she adds. "It's evident in the content, but it's also based in the time-honored technique of printmaking. He accepts modern amenities but insists on respecting the past." For example, new facilities such as the Haneda International Airport are juxtaposed with traditional structures, such as the Asakusa Kannon Temple, whose main building was spared in the earthquake and became a symbol of survival.

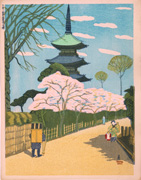

Rather than portray the actual devastation and resulting pain and dislocation caused by the earthquake, Koizumi's prints look forward, to a future bright with promise. Yamashita Entrance to Ueno Park, completed in September 1931, depicts the area once associated with the enormous refugee camp created in September 1923 to manage the displaced residents of Tokyo. Koizumi contrasts the memory of turmoil with the peacefulness of 1931, a time when women can walk alone at night and in Western dress.

In both of the prints Yamashita Entrance to Ueno Park and Subway in Spring (March 1937), "we also see how women enjoyed new freedoms in Koizumi's depictions of this newly modern city," Lamonaca observes. Subway in Spring portrays young girls traveling to a modern department store, eager to participate in consumer culture, and unescorted by men.

"Along with the introduction of modern amenities, such as a subway and department stores, the creation of this imperial city included an airport and other facilities implicated in the military buildup that led to the Second World War," Lamonaca says.

By the time Koizumi developed Haneda International Airport in March 1937, Japan had become an aviation powerhouse, and claimed a substantial airplane manufacturing capacity. Military aircraft had already been victorious in numerous excursions over China and Manchuria.

When Koizumi produced Army Shooting Range at Okubo in August 1937, the China war had already started. Koizumi was so impressed that the elite soldiers of Japan were training at such a firing range that he wrote, "The sound of live fire is invigorating."

Representative of the individual artist-printmaker sosaku hanga (creative print) movement that was emerging at the time, Koizumi worked directly with the materials, actually carving the blocks himself and making the prints. The resulting prints reveal highly personalized interpretations of the city and its meanings.

"The Koizumi series is a perfect fit for The Wolfsonian and its mission: a neglected group of prints that can be studied for the multiple stories they tell about the many roles of art as observer, critic, and enabler of social change as a society encounters modernity," notes co-curator James T. Ulak.

Photographs and contemporaneous documents will complement the print display. A catalogue co-authored by Ulak, Lamonaca, and Frederic A. Sharf, collector and independent scholar, will consider the Koizumi ensemble in the context of art history and the social trends of the period.