Prints in Collection

Novel Growth No. 2, 1958

IHL Cat. #1231

Ground No. 3, 1959

IHL Cat. #148Stone Garden of Kyoto, undated

IHL Cat. #386

Biographical Data

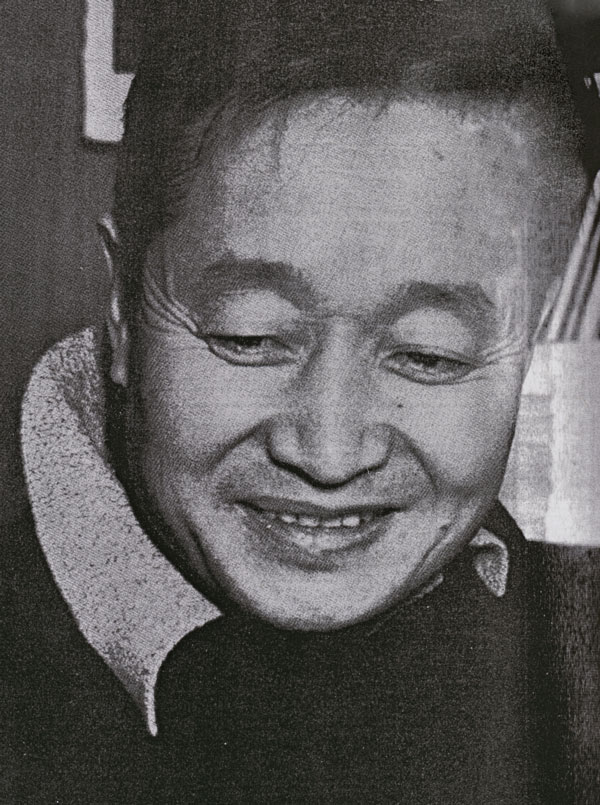

(Source: The Contemporary Artist in Japan, David Kung, East-West Center Press, Honolulu, 1966, p. 159) | ProfileYoshida Masaji 吉田政次 (1917-1971) Source: John Fiorillo's website http://www.viewingjapaneseprints.net/texts/sosakutexts/sosaku_pages/masaji3.htmlMasaji Yoshida was one of the most skilled pupils of Onchi Kōshirō (1891-1955), a founder of the sosaku hanga movement. Onchi encouraged his students to experiment with woodblock carving, printing, and compositional techniques. One of Masaji's early print series was a set of bold black and white geometrical prints, titled Fountain of Earth. As Masaji continued to explore new approaches toward abstract design, he turned toward softer shapes in subdued colors. He developed a method of cutting his various color blocks from a single board and then fitting them back together within a frame that permitted raising each piece separately when it was needed to print a specific color area. Masaji did not use the typical registration method (kentō); rather, he tacked the paper to the edge of the frame. Masaji used heavily dampened, unsized paper to make the colors spread and produce a blotting-like effect, while also imparting soft edges to the shapes. He also printed muted shades of gray over his principal colors to add further depth and interest to his designs. |

Biography

Masaji Yoshida was born in Wakayama and lived there until he finished middle school, when he moved to Tokyo. After studying drawing from casts for a year at a private preparatory school he entered the government art academy at Ueno. It was in this period that Hiratsuka (a founder of the sōsaku hanga movement) was teaching his extra curricular course in hanga. "I enjoyed the class," says Yoshida. "I had no idea of making prints, but I liked them and I thought it would be interesting to know more about them."

Graduating from Ueno in 1942, Yoshida was immediately drafted into the army. Within a week he was on his way to China, and after a month's basic training there he was sent to the front. A year later he was back in Kyushu for six months officers' training, and he returned to China as a warrant officer. This time he drew a commanding officer who liked art, and for the first time since Ueno he was given some free time to sketch. He was promoted to sublieutenant and then, seriously wounded in action, was hospitalized for six months, still in China.

With the armistice, his unit became prisoners of war and it was more than half a year before they were returned to Japan. Although a captive, he had freedom to roam about and sketch, and often he exchanged a drawing for a bowl of noodles. When he found he would be allowed to bring no sketches back to Japan he gave them all to the peasants.

He was repatriated in March 1946, and after a couple of weeks at home he went back to Ueno for a year of postgraduate work. "We lived like vagrants in that first postwar year," he remembers. "Some of us lived in what had been one of the school's tearooms, and we burned wood in open fires on the floor to get a little warmth."

During this postgraduate year he began to teach art at a public high school on a part-time basis, and when he had finished at Ueno he became a regular teacher. "Because I'm a print-maker, I suppose I've slanted my course toward hanga," he says."My students are very enthusiastic about making prints, and they're doing fine work." Samples by seventh and eighth graders indicate that the standard is extraordinarily high in both black and white and color. Yoshida is proud of their work, proud that he is usually consulted on any international exchange of students' prints, and proud that, in a successful book on scenes of Tokyo illustrated by children, all but two or three of the prints were made in his classes.

Turning to Prints

Asked how he happened to turn to prints after starting out in oil, Yoshida replied that there were a number of reasons. "A minor one is that after the war the available oil paints were of very poor quality. More important, Kitaoka [Kitaoka Fumio (1918-2007)] began to make prints in earnest and his work showed so much improvement over his oils that I couldn't help but be impressed. Furthermore, my own work was progressing toward the abstract and two dimensional, and I became convinced that for what I was trying to do the print is more suitable than oil." He pointed to some of his own abstract oil paintings in tones of grey, and to nearby prints in the same manner. "Those oil paintings fail completely--the whole effort comes perilously close to house painting--and yet in prints the same ideas are effective."Abstraction

"I first became interested in abstract art at Ueno before the war. But it was Onchi [Onchi Kōshirō (1891-1955)], after the war, who gave me the impetus to do abstract work. Within the Hanga Association we set up a study group with Onchi as the leader. As I listened to him I found that he expressed many ideas I had long felt, and this gave me the confidence I needed.I'm the kind of artist who wants, not to develop new ideas, but to do something new. For many years my style was molded by reaction against my wartime experience. Life in the army was rough, confused, and violent. I'd had more than enough of that, but when I returned to Tokyo and went to see a large major exhibition I found that the whole show was battle itself. It set me to thinking. I wanted something orderly and serene and peaceful, and I decided on quiet grays in simple vertical and horizontal forms. My titles give a clue as to what I was seeking: some of my earliest work is a series called Silence.

As I look back it's as though I had fled from the chaos of war to the peace and quiet of the desert. It was good for me, but after a while I needed something else and I left the desert for the forest. My new prints are conceived with a feeling of vigor and growth. From small prints I turned to big ones and from muted grays to the force of black and white. It was a major transition and it took me six months to resolve the design for the first one."

A Choice: Woodblock Prints over Oil Painting (The Artist's words)

Source: The Contemporary Artist in Japan, David Kung, East-West Center Press, Honolulu, 1966, p. 158"Why did I switch from oil to woodblock prints? There is no clear answer. I was subconsciously attracted by the effect of lines produced in woodblock work. I found a great sense of reward in seeing the traces of my chisel and knife. Woodcut lines are tender and warmer and are very human and Japanese in sentiment, while etching is basically a free-hand exercise on a copper plate.

My long career of woodblock prints could be divided chiefly into three phases. The first phase was a period of optimism. My lines were straight and geometric in design - bold and exhilarating. Then, in my second stage, my work became more withdrawn. During this period I was very much affected by the death of our only son. My lines tended to become nervous, sensitive, oblique. The lines developed into sharp needle points. My colors are dark - a shade of brown mixed with light red, Indian-red,and white - and they represented the colors of sorrow and destruction. Ironically, my work began to gain acclaim both at home and abroad. This style, which served as a safe island where I could hide my wounds, persisted until recently. Now I feel that I should come out of this self-imposed seclusion. I want to bring out a sense of space, which is difficult in woodblock prints."

Critiques

James Michener

Source: The Modern Japanese Print - An Appreciation, James Michener, Charles E. Tuttle Co., 1968, p. 48-49Masaji is the most intellectual of the print artists, a man of exquisitely refined tastes who has been encouraged by a small coterie of admirers to pursue his highly individualistic art. He makes his living teaching in public schools, for his prints have never sold in large enough quantities to support him, and his influence is widely felt in the school system.

Four Categories of Work

His mysterious prints, for it would be impossible to describe them in any other way, fall into four clear categories.First Category: At the end of the war, when he found destruction throughout his city and color running wild in the paintings of his friends, he retreated to a severely cauterized world of gray marked by symbolic figures. These prints were distinguished by an autocratic control which stood in contrast to the chaos he saw and felt about him. They are handsome works, large and clean and impressive.

Second Category: Masaji progressed to an even more austere vision of the world, depicted in a series of brilliant, immense prints titled "The Fountain of Earth." These consist of rigidly disposed series of straight black-and-white lines dominated here and there by large black or white circles. They are stunning prints, some of the most dramatic ever to have been released in Japan, and as decoration they are superb.

Third Category: Masaji’s third kind of print [of which Novel Growth No. 2 is an example] formed a radical departure and was occasioned, as such new forms ought to be, by a personal crisis within the conscience of the artist. The prints appear mostly in purple and black and always with a swarm of closely knit lines… The designs are tortured, involuted, brooding, and the mysterious colors effectively represent the spirit of the work. These are most distinguished prints, not widely favored by collectors but cherished by those who know the artist and who are concerned with the artistic problems inherent in the modern school of woodblock prints. What dark experience of the soul called forth this series I do not know, but during its issue Masaji’s son died, and the prints form a fitting memorial to this tragedy, although they were not originally called forth by it. Connoisseurs of the exquisite in art should know these prints, for they are some of the most expert issued in Japan, veritable masterpieces of printing and color. They exhibit no quick allure and one comes to them quietly after having known other prints that on the surface are much more enticing; but when one has discovered their quiet mastery one recognizes in them a milestone in contemporary Japanese woodblocks.

Fourth Category: They have the subdued color harmony of the first type, the exquisite control of design that marked the second, and the mysterious lines and color harmonies of the third, all blended to produce a simplicity that is compelling. [Ground No. 3 is an example of this category.]

Lawrence Smith (Former Keeper of Japanese Antiquities and Keeper Emeritus, The British Museum)

Source: Modern Japanese Prints 1912-1989, Lawrence Smith, British Museum Press, 1994, p. 61.In the early 1960s Yoshida was doing a lot of work of great density and intensity using only one main ink block carved with considerable detail in herringbone patterns and printed over one or two grainy colors. His earlier practice of carving all of his blocks from one surface. like a jigsaw puzzle, had given him a notably unified approach to the production of his prints. Unlike Onchi or any of his other main pupils, whose work was characterized by elegant, lyrical and even detached abstraction, Yoshida's work increasingly displayed a sense of menace, despair or unease.

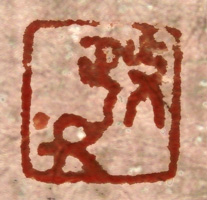

Artist's Seals

seal on Ground No. 3 |  |

Literature

The Modern Japanese Print: An Appreciation, James Michener, Charles E. Tuttle Company, 1968, p. 48-50Modern Japanese Prints 1912-1989, Lawrence Smith, British Museum Press, 1994, pp. 16, 38, & 61; plates 103-106

Modern Japanese Prints: An Art Reborn, Oliver Statler, Charles E. Tuttle Company, 1956, p. 148-152; plates 84-85.

Contemporary Japanese Prints, Michiaki Kawakita, Kodansha International Ltd, 1967, p. 187, plates 18, 76