| Nature, 1974 IHL Cat. #719 | Where It All Began, 1976 IHL Cat. #892 | Mountain and Lake, undated (likely post-1980) IHL Cat. #698 |

Mini Print B, undated (c. 1980s)

IHL Cat. #1270

Mini Print G, undated (c. 1980s)

IHL Cat. #1271

Miniprint Y, undated (c. 1980s)

IHL Cat. #1269

Dockyard 造船所, undated (c. 1980s)

IHL Cat #1113

Backlit Fuji 逆光富士, undated, (c. 2000)

IHL Cat. #1112

Biographical Data

Biography

Miyashita Tokio 宮下登喜雄 (1930–2011)Sources: The Japanese Print Since 1900: Old dreams and new visions, Lawrence Smith, British Museum Publications Ltd., 1983; Japanese Prints Today: Tradition with Innovation, Margaret K. Johnson, Dale K. Hilton, Shufunotomo Co., Ltd., 1980, p. 212-219; Collecting Modern Japanese Prints, Then and Now, Mary and Norman Tolman, Charles E. Tuttle Company, 1994; p. 150, 233, Guide to Modern Japanese Woodblock Prints: 1900-1975, Helen Merritt, University of Hawaii Press, 1992, p. 93; 44 Modern Japanese Print Artists, Gaston Petit, Kodansha International Ltd., 1973, p. 46-47 and as footnoted.

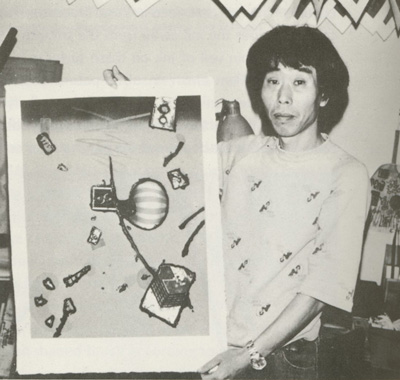

Japanese Prints Today: Tradition with Innovation, 1980, p. 218. | Best known for his intensely colored prints created from a combination of woodblock and metal plate processes, Miyashita was born in 1930 in Tokyo. He was the son of a metals dealer, giving him access to many of the tools and materials required to work on metal plates, one of several media he employed in print making. Miyashita must have shown an early affinity for woodblock prints, as a middle school teacher enabled him, while still in high school, to study woodblock print making with Hiratsuka Un'ichi (1895-1997), one of the founders of the sosaku hanga movement, from 1946 to 1948. In 1950, while attending Meiji University, he studied metal plate print making with Komai Tetsurō (1920-1976) and Sekinō Jun’ichiro (1914-1988). He went on to graduate from Meiji University’s department of literature in 1951. He was active, starting in 1955 and throughout his career, with Nihon Hanga Kyōkai (Japan Print Association) and was also a member of the Japan Copper-Plate Artist Association. In 1979 Miyashita traveled to |

Writing in 1980, in Japanese Prints Today: Tradition With Innovation, Hilton and Johnson provide this glimpse of the artist’s life:

| Miyashita lives with his wife and children in a pleasant home at the end of a long lane lined with trees, away from the center of Tokyo. His second floor studio is airy, colorful, and efficient; it reminds us of his prints. Red and blue chairs, a large table, an etching press, and racks with hanging tools dominate one side of the room. Across the room on the floor facing a window-wall is the woodblock-printing center: a zabuton (cushion) to sit on, and a low table to print on. Within reach are barens, brushes and many bowls and jars of bright-colored inks.… Miyashita’s workspaces reflect dramatically the contrasting methods he uses to create his prints; the simple baren and the massive etching press are symbolic, each one a pressure tool to get ink onto a print. |

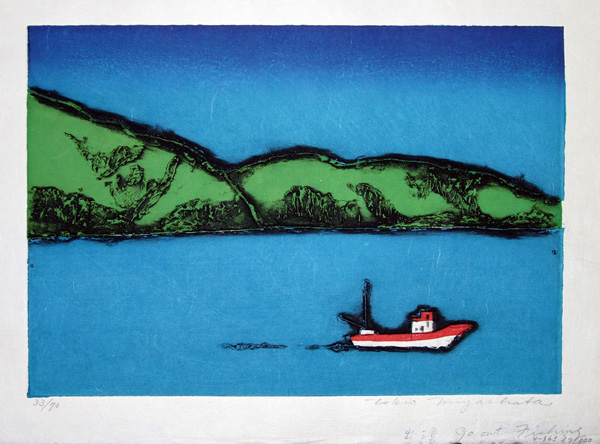

Going Out Fishing, undated | “If people see the green and water in my print and like what they see, it is enough. I do not seek philosophical meanings. I use bright colors to show the bright side of life.” - T. Miyashita. |

Combined Process Prints – “East meets West”

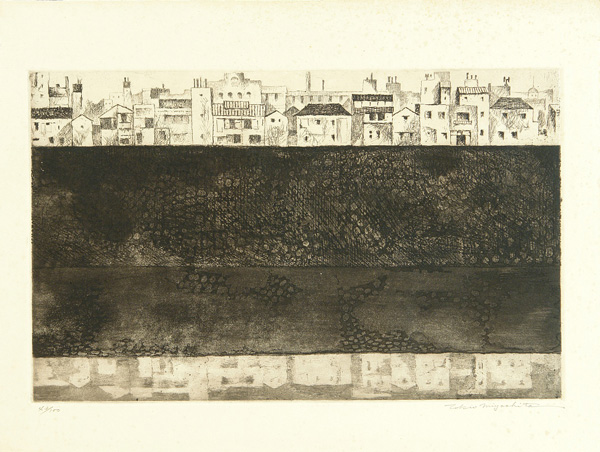

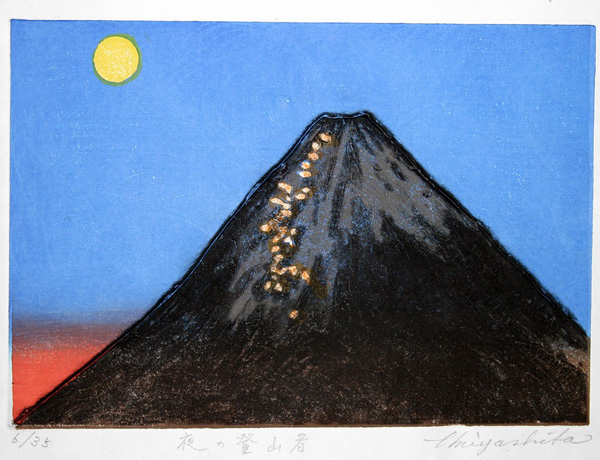

Miyashita’s “early prints, before 1962, depicted the waterfront region of Tokyo where Miyashita was born... [such as the 1959 print Kawagishi below] [L]ater prints are characterized by rugged lines made by soldering wires onto a zinc plate and printing, sometimes in combination with photoengraving, against brilliantly colored backgrounds printed by woodblock.”| Kawagishi (Riverbank), 1959 etching from "Gendai Meika Sosaku Hanga Shu" (Prints by the famous, contemporary Sosaku Hanga artists) An example of Miyashita's early work | Autumn Evening, 1975 (print is undated) An example of Miyashita's abstract work The British Museum 1982,0624,0.5 | Mountain Climbers at Night, 2006 (print is undated) Miyashita's later work moved back towards realism |

“And a challenging marriage it is, of traditional Japanese and traditional European processes. Miyashita uses the Ukiyo-e woodblock technique requiring water-based inks and absorbent paper. On the same print he uses intaglio techniques demanding oil-based inks and a paper that responds sensitively to these inks, and, at the same time is strong and resilient enough to take the pressure of the etching press. Kikuzi Kozo is the paper that has the necessary characteristics. It has tough fibers and accepts both water-based and oil-based inks. To offer the appealing characteristics of both processes, Miyashita prints color areas from woodblocks and overlays these with details and contours printed from an intaglio plate inked in black."1

The Print Process in Detail

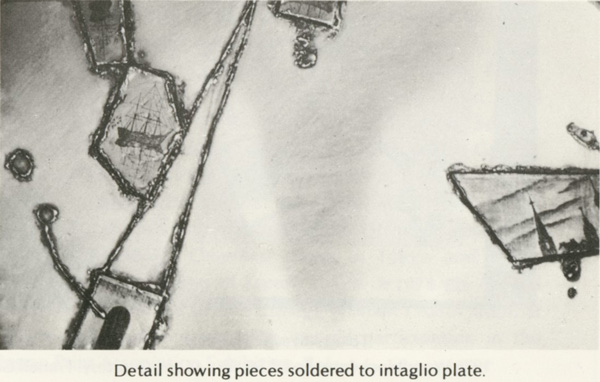

Source: Japanese Prints Today: Tradition with Innovation, Margaret K. Johnson, Dale K. Hilton, Shufunotomo Co., Ltd., 1980, p. 214-216.| He first composes and assembles the intaglio plate cut from a zinc sheet to appropriate print size. On the plate he assembles assorted sizes and shapes of zinc or copper plate with details added by etched or scratched lines. Sometimes he adds found objects, such as stamped metal fragments or even old photo-engraved plates… Miyashita moves these pieces around on the plate until he achieves an effective juxtaposition.... [W]hen Miyashita is satisfied with his composition, he solders the pieces to the plate. The next step is to decide what the colors of the shapes and background areas will be and to plan how many blocks are needed for the color separations. Where color areas are far enough apart to avoid mingling of the different colored inks, he can use one block to print several colors. Otherwise he must use a separate block for each color. The blocks must be the same size as the zinc plate. The image is then transferred from the plate to these woodblocks. To do this, he inks the plate image, wipes off the excess ink, and places the plate on the bed of the etching press. He lays a paper over this and runs both through the press, thereby transferring the inked image onto the paper. Next he places the paper, ink-side down on the woodblock, and rubs the top side with a baren to transfer the ink from the paper to the block. This transfer process is repeated for each block he will need. This method of double-transfer – from plate to paper to block – assures a positive image on the woodblocks in proper registration with the metal plate. If the image were transferred directly from plate to block, the image would be in reverse as seen through a mirror. The blocks are now ready to be carved. Miyashita cuts away the parts of the block not to be printed; the small shapes to be printed are left as islands on the plywood sheets, while the background areas are left intact except for the smaller shapes which he carves away – the same shapes that are islands on other blocks. When the blocks are cut, he is ready to ink and print them in the standard Japanese method. Miyashita uses poster-colors directly from the jar, diluting them as needed with water. He does not mix colors before applying them to the block. He does, however, merge one color into another on the block to create bokashi effects… To do this consistently from print to print in an edition, he marks his clothesbrush-shaped brush according to where to load the colors. With the colored inks in the brush he sweeps it across the block precisely along the same course for each print. To build up the pigment on the paper sufficiently in both the bokashi and the flat-color areas, Miyashita may need to brush each color onto the block many times to make repeated printings. By this means, he achieves the velvety rich colors characteristic of his work. All of the color areas must be printed on each paper of an edition before the intaglio image can be printed over them. He then hangs the paper to dry. Before printing the zinc plate he must wet the prints again using a wide brush to lightly spread the water. Miyashita then inks the zinc plate. He rubs the black oil-based ink over the entire surface, working it into all the crevices. Then he carefully wipes the ink away from the smooth surfaces. If he leaves a thin veil of ink on these surfaces by choosing not to wipe them clean, a subtle patina is added to the whole print, deepening the richness of the underlying block-printed colors. It is the different thicknesses of black ink – form the heavy black around the rough solder contours, to the delicate tones of the etched, and drypointed details – that add the jewel-like quality to the imagery. While the solder-contours may look crude on the plate, these same projecting lines, when inked and printed, make a natural looking soft outline for the shapes of color they encompass. By combing two techniques of vastly different origin and character, Miyashita has melded his own form of expression: bold, bright, rough-hewn, yet refined and singularly elegant in effect. The viewer’s imagination may bring its own meaning to the work or the visual feast itself may be enough. |

"A Superb Colorist"

In discussing Miyashita’s more abstract work, J. Thomas Rimer, American scholar of Japanese literature and drama, states:“A superb colorist, he transmutes his shapes, some recognizable, some not, into a series of visual juxtapositions that possess ultimately a formal logic all their own. Some critics have compared the abstracting techniques of Miyashita to those of Joan Miro, the Spanish painter first associated with Pablo Picasso, then with the surrealists in Paris. Both employ shape and color in compositions that reveal remarkable and subtle balances placed to a achieve a powerful formal harmony.”2

Undated Prints

Miyashita does not date his prints, making it difficult to confirm when works were created. According to Petit this lack of dating, not unique to Miyashita, is because of some Japanese artists' “uncertainty as to how to date them - according to the year the blocks were produced, or according to the year when the actual printing was accomplished.”3Exhibitions and Awards – Partial List

In 1957 showed work at the Shunyōkai exhibition, winning an award. He would continue to show work at this exhibition. Represented at the Asahi Exhibition of Outstanding Work in 1960, 1965, and 1966. Has exhibited regularly at the Tokyo International Print Biennale, winning the Minister of Education Award in 1964. Took part in the Ljubljana International Print Biennale in 1965 and the Sao Paulo Biennale in 1967; London International Print Biennale, 1968; 1973 Lugano Switzerland, international print Biennale and multiple shows of contemporary prints in the United Kingdom; 1981, World exhibition of contemporary prints [Tokyo]; 1983, Italy international print Biennale; 1984, Xylon International Print Triennale in Switzerland, Italy, Germany; 1987, granted travel-study fellowship by Japanese Cultural Affairs Agency; 1990, 20th Century Drawings exhibition, Cincinnati Museum of Art; 2006, the East/West Exchanges HANGA wave in Tokyo and the 4th International Print Biennale, Italy; 2010, Japan Print Association recognizes Miyashita's lifetime achievements.Collections (partial list)

Art Gallery University of Maryland; Art Institute of Chicago; Brooklyn Museum; Honolulu Academy of the Arts; Los Angeles County Museum of Art; Portland Art Museum, Portland, Oregon; University of Michigan Museum of Art; Art Gallery of New South Wales; National Gallery of Australia; National Gallery of Canada; University of Alberta Art Collection; British Museum; The National Museum of Modern Art, Osaka; The National Museum of Art, Tokyo.1 Japanese Prints Today: Tradition with Innovation, Margaret K. Johnson, Dale K. Hilton, Shufunotomo Co., Ltd., 1980, p. 213.

2 A Lyrical Impulse in Modern Japanese Prints and Poetry, J. Thomas Rimer, Asian Art, Volume II, Number 1, Winter 1989, pp. 29-55.

3 44 Modern Japanese Print Artists, Gaston Petit, Kodansha International Ltd., 1973, p. 225.