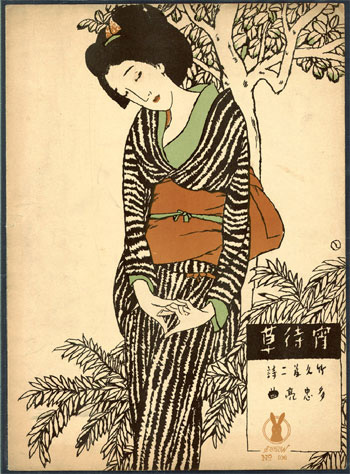

Prints in Collection

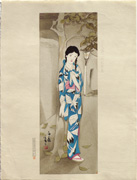

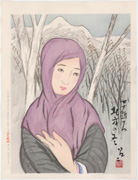

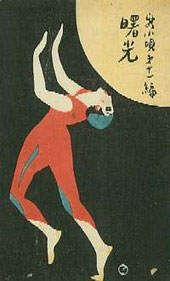

Spring Glance

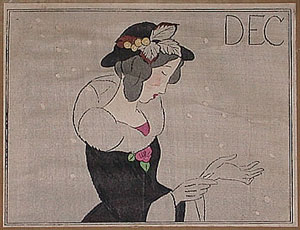

from the Magazine

The Ladies' Graphic, 1924

IHL Cat. #1725

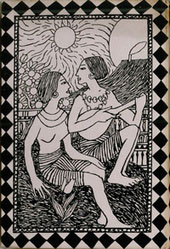

Hometown of the Sea (Furusato no umi) from the series A Collection of Poetry and Prints by Yumeji, 1941

IHL Cat. #1788

Cove of Oranges, 1963

(after a 1912 design)

IHL Cat. #344

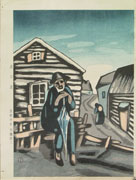

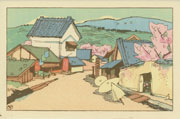

Landscape with village and two women, 1963

(after an earlier design)

IHL Cat. #358

Fireworks, undated

(after a 1915 design)

IHL Cat. #942

Early Summer, undated

(after an earlier design)

IHL Cat. #1346

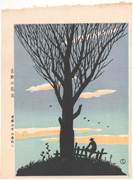

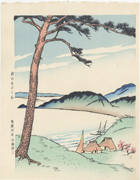

Asaki Haru, undated

(after a 1919 design)

IHL Cat. #1362

Wind, c. 1940s (undated)

IHL Cat. #1789

- intentionally left blank -

Chinese Ship Shop,

c. 1970s/1980s

(after a 1919 design)

IHL Cat. #749

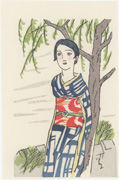

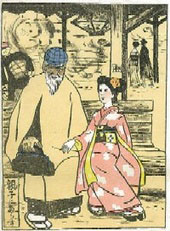

Yanagi yu,

c. 1970s/1980s

(after a 1915 design)

IHL Cat. #2230

IHL Cat. #2253

| Senow 341 Vamp, 1924 IHL Cat. #563 | Senow 365 Hakone-no-Yama, 1924 IHL Cat. #561 | Senow 623 Album-Leaf, 1925 IHL Cat. #562 |

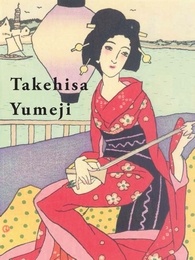

Biography

Sources: British Museum website http://www.britishmuseum.org/research/search_the_collection_database/term_details.aspx?bioId=143481; Modern Japanese Woodblock Prints - The Early Years, Helen Merritt, University of Hawaii Press, 1998,p. 23-31 and as footnoted.Born Sept. 16, 1884 in the Okayama Prefecture village of Honjo to the son of a sake wholesaler, Yumeji had no formal art training. It is said that while still a teenager he learned the art of line while working with a brush-maker. In 1901 at the age of seventeen his father sent him to Tokyo to study business at the private Waseda School where he developed a wide circle of friends that included Christians and leftists. While a student, Yumeji began submitting illustrations to magazines and by 1905 he had left Waseda, finding that he could make a living selling his art.

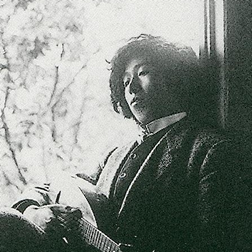

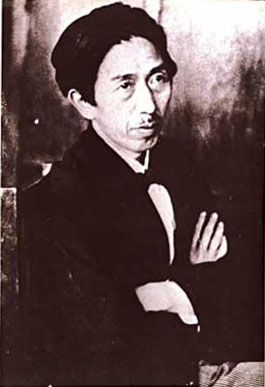

undated photo | After leaving Waseda he lived with socialists, sharing their sympathy for the working class and creating a number of political drawings. These drawings were published in the socialist paper Shukan chokugen (Weekly Plain Speaking) and he subsequently made drawings (under a pseudonym) for the socialist magazine Hikari and the socialist newspaper Heimin Shinbun. When Heinmin Shinbunwas closed down by the government in 1907, Yumeji retreated from activepolitics “and turned to the expression of poetic feelings.” He was,however, to remain deeply interested and effected by social issues theremainder of his life. In January 1907 Yumeji married Kishi Tamaki, who ran a postcard shop inTokyo. Thereafter he did a lot of design for postcards and other ephemera.Their relationship was extremely turbulent from the start and soonended in divorce in May 1909, though they remained attracted to eachother and continued to work together. |

1910 poster from first solo exhibition | In 1909 his first book of sketches and poems was published, Yumeji Picture Collection – Spring Volume (Yumeji gashu - Haru no maki). About these sketches hesaid “I am going to write a poem using pictures instead of words.” The emotional images he created were rife with nostalgia of thefloating world found in traditional ukiyo-e prints. In 1910 he had hisfirst solo exhibition. (The poster from the exhibition is shown on theleft.) The large-eyed, thin, sad beauties he created, based on his wifeTamaki and on subsequent mistresses, became the standard romantic imagefor his generation and they were eagerly bought by both young men andwomen. His style was heavily influenced by German 'Jugendstil' (as Jugendstil was itself influenced by ukiyo-e) and he studied the German magazines Jugend and Simplicissimus along with the works of the German Jugendstil artist Heinrich Vogeler (1872-1942). Yumeji was also heavily influenced by the painter Fujishima Takeji (1867-1943)whose paintings captured the romantic spirit of the times. In 1913 his celebrated book of poetry Dontaku (Holiday) was issued, with book design by Onchi Koshiro (1891-1955) who had become a friend. It included the poem Yoimachi-gusa (Evening Primrose) which was set to music in 1918 and became a big national success. I wait even though I know she will not return. My heart sinks in melancholy like the evening primrose. It seems that the moon will not appear tonight - Evening Primrose by Takehisa Yumeji |

Between 1914 and 1916 Tamaki and Yumeji founded and ran the Minato-ya shop in Tokyo which sold moku hanga (woodblock prints) and other paper goods which he designed. Yumeji created drawings specifically designed to be turned into prints. The blocks may have been carved by Igami Bonkotsu or Okura Hanbei and were printed by Hirai Koichi. Minato-ya attracted a “sophisticated clientele and became something of a gathering place for Tokyo’s more progressive artists” and Onchi’s Tsukubae group held an exhibition there soon after the shop opened.1

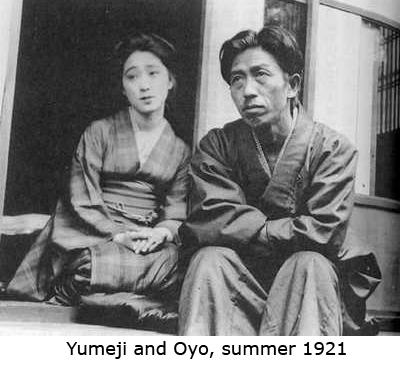

In 1914 he met Kasai Hikono, who became his mistress, but who died early and tragically in 1920 at the age of twenty-four. In 1916 he became chief editor of illustrations for the Shin-shōjo (New Girls), a magazine by the publisher of the nation's oldest women's magazine, Fujin no tomo (Woman's Friend).2 (See the heading "The Shōjo Girl" below for a discussion of the shōjo

|  |  |

| Fireworks, woodblock print for cover of the magazine "The Ladies' Graphic" 1924 | Autumn tune, woodblock print for cover of the magazine "The Ladies' Graphic" 1924 | Wind of Snow, woodblock print for cover of the magazine "The Ladies' Graphic" 1924 |

In 1931 Yumeji traveled to the United States and Europe, largely to escape the stifling effect of rising militarism in Japan. In Berlin he delivered a lecture in which he called lines the “essence of art” because they express inner life. Lines, he said, are not to depict objects but to transmit the artist’s spirit. He returned to Japan in 1933, troubled by the rise of Nazism and the parallels he saw with Japan’s militarism.

Shortly after his return he checked into a sanitarium in Nagano. He died there at the age of fifty. Yumeji Takehisa is buried in the Zoshigaya cemetery in Tokyo.

1 Images of a Changing World: Japanese Prints of the Twentieth Century, Donald Jenkins, Portland Art Museum, 1983, p. 55.

2 Website of Kodomo no kuni The International Library of Children's Literature / National Diet Library http://www.kodomo.go.jp/gallery/KODOMO_WEB/authors/takehisa_e.html

3 Being Modern in Japan: Culture and Society from the 1910s to the 1930s, Elise K. Tipton and John Clark, University of Hawaii Press, 2000, p. 204.

The Shōjo Girl

Source: "Yoshiya Nobuko, Out and Outspoken in Practice and Prose," Jennifer Robertson, appearing in The Human Tradition in Modern Japan, edited by Anne Walthall, Wilmington: Scholarly Resources Books, 2002, p. 157-158In 1915, Yumeji collaborated with Yoshiya Nobuko (1896-1973), one of Japan's most successful woman novelists, illustrating a number of her stories. Nobuko serialized novels appearing in various women's magazines were immensely popular, as was Yumeji's work, with a new audience, the shōjo, or girl. (Literally, a “not-quite-female female.”)

A “really real” female was a married woman with children. The so-called shōjo perioddefined the emergent space between puberty and marriage that began togrow into a life-cycle phase, unregulated by convention, as more andmore young women found employment in the service sector of the newurban industrializing economy. Included in the shōjo category were the “new working woman” and her jaunty counterpart, the flapper-like “modern girl,” or moga (modan garu), who was cast in the popular media as the antitheses of the “good wife, wise mother.”

Yumeji's Song Sheet Designs

| Cover for Yumeji's composition Evening Primrose (Yoimachigusa), 1918 Designed by Takehisa Yumeji |  Siz Yumeji-designed score covers make up part of this collection, IHL Cat. #s 561, 562, 563, 564, 565, 2253. |

Yumeji’s Prints

Smith states that "technically excellent prints" were produced after his paintings and drawings both during and after his lifetime. He goes on to say: "In themselves these prints represent a further conflict, for they are on the one hand reproductive and on the other genuine and successful attempts to convey the flavour of a most individual artist."2

Paper Lanterns, c. 1914

Image from Takehisa Yumeji Ikaho Kinenkan website

2 The Japanese Print Since 1900: Old dreams and newvisions, Lawrence Smith, British Museum Publications Ltd., 1983, p. 20-21.

Museums Dedicated to Takehisa Yumeji

There are at least three museums in Japan dedicated to the works of Yumeji; one in the Ueno, Yanaka area of Tokyo, one in his home prefecture of Okayama and on in Kanazawa.Takehisa Yumeji Museum, Bunkyo-ku,Tokyo

Source: Website of the Yayoi Museum & Takehisa Yumeji Museum http://www.yayoi-yumeji-museum.jp/

The Takehisa Yumeji Museum opened on November 3, 1990. The museum houses collections of Yumeji's works owned by lawyer and curator Takumi Kano, and is located in Hongo where Yumeji stayed in the Kikuhuji Hotel. Yumeji also enjoyed meeting his dear lover, Hikono Kasai, in Hongo. Hongo is surrounded by both tranquility and the greenery of trees, reminiscent of days of old. You can enjoy extensively the romance of the Taisho Era, including not only pictures of Yumeji's style of depicting beautiful women, which may remind you of the good old days, but also works reflecting attempts at modern design at our museum, which is the only museum exhibiting the works of Yumeji in Tokyo.

Exhibition Activities

We conduct a special exhibition every three months (January - March, April - June, July - September, October to December). For the special exhibitions, we plan to show various themes reflecting both the life and art of Yumeji. We explore deeply these themes as a museum which researches the works of Yumeji. We have 200-250 works of art drawn by Yumeji Takehisa on constant display.

Yumeji Art Museum, Okayama, Japan

Source: Website of the Yumeji Art Museum http://www.yumeji-art-museum.com/07_index-e.html

About Yumeji TakehisaThe Yumeji Art Museum is dedicated to Yumeji Takehisa (1884-1934), who became one of the most famous leading Japanese painters during the Taisho era. He also played an active role as a poet and illustrator.

Yumeji was born in Okayama, Japan. Yumeji’s art is believed to have been inspired by the beautiful nature of his hometown and the memories he treasured of his family and friends. During the Taisho era, the beautiful-eyed women of his paintings were popular as Yumeji Bijin-ga. His fantastic works were beloved by many people of all ages. In addition, Yumeji was called the “modern Utamaro” and became widely known as the Japanese ”Toulouse-Lautrec and Edvard Munch”. Even now, his artistry is evaluated highly not only in Japan, but also in many foreign countries.

The Yumeji Art Museum introduces the great artist Yumeji Takehisa who was born in Okayama.

Kanazawa Yuwaku Yumeji-kan Museum

Recent Exhibitions

"Takehisa Yumeji in the Memory"

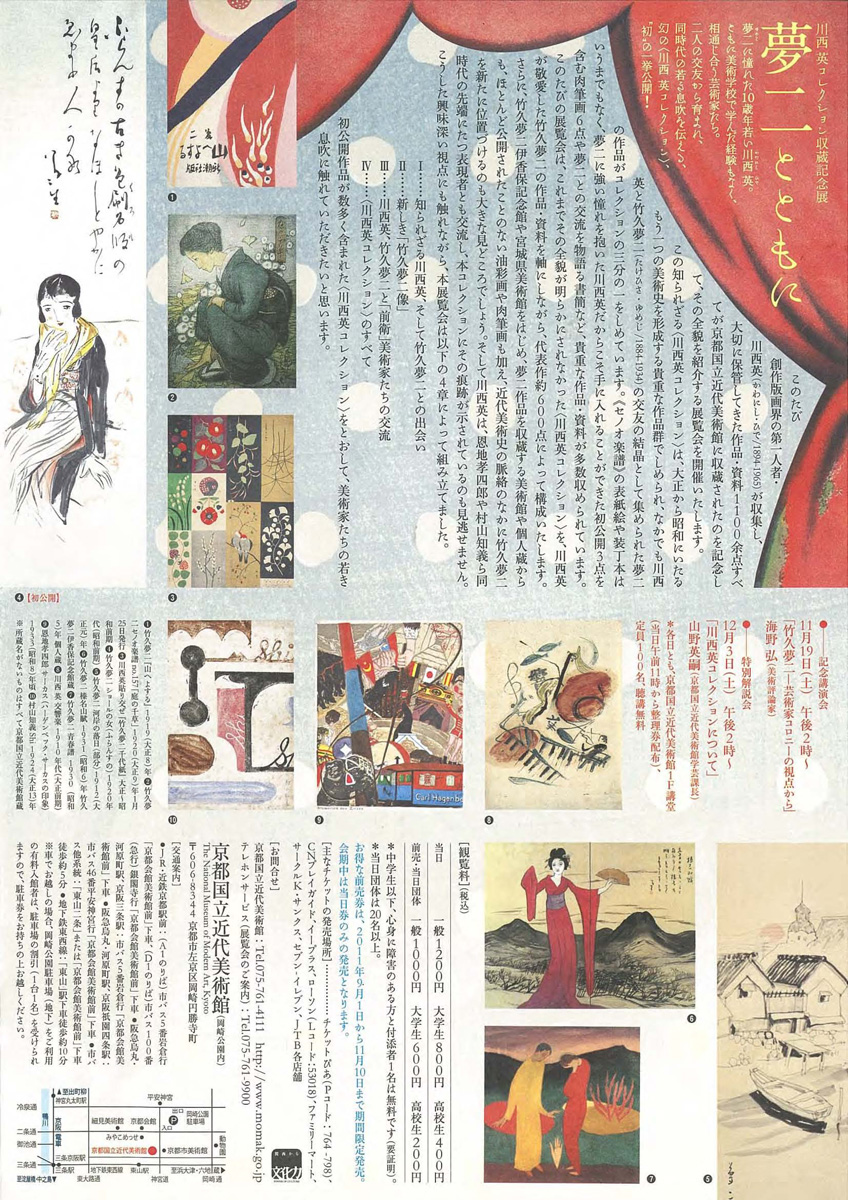

Commemoration of acquisition: The Kawanishi Hide Collection

The National Museum of Modern Art Kyoto

From 2011-11-11 to 2011-12-25Source: "Takehisa Yumeji in the Memory: Commemorate of Acquisition of the Kawanishi Hide Collection," Tomoko Hori, The Japan Times

The Kawanishi Hide Collection of some 1,100 artworks was established by the Kobe-based printmaker Hide Kawanishi (1894-1965). One of its highlights is the work of Yumeji Takehisa (1884-1934), a popular Japanese painter with whom Kawanishi exchanged letters. Kawanishi treasured and kept Takeshisa's letters in scrapbooks, and his collection of artworks is said to have been based on the artists' friendship.

To commemorate the acquisition of this collection, which the National Museum of Modern Art, Kyoto, has been working on since 2006, this exhibition showcases around 600 works by Kawanishi and Takehisa. Although many exhibitions of Takehisa's work have been held in Japan, this show presents some rarely shown oil paintings and original drawings; till Dec. 25.

"Takehisa Yumeji and Taisho Roman" Exhibition - Takehisa Yumeji Museum

From 2010-01-03 to 2010-03-28Source: Tokyo Artbeat website http://www.tokyoartbeat.com/event/2009/9272.en

| Despiteits short span of only 15 years, the Taisho Period (1912-1926) saw therise of cultural lifestyles amid the influx of Western culture and asweeping tide of modernization. Furthermore, a new female cultureburgeoned, providing women with a chance to acquire education and jobsas "new women". Centering on art and romantic records of painter and symbol of theTaisho period, Takehisa Yumeji, this exhibition introduces women'slifestyles of the time from various perspectives. |

"Yumeji Graphic" Exhibition - Takehisa Yumeji Museum

From 2009-04-03 To 2009-06-28Source: Website of the Yayoi Museum & Takehisa Yumeji Museum http://www.yayoi-yumeji-museum.jp/

In November 1905, Yumeji Takehisa started his career as a painter at the age of 22 after submitting an illustration piece to the magazine "Chugaku Sekai (the Middle School World)". At a time when nihonga painters were dominating the field of book illustration, Takehisa's work dealing with everyday motifs left a strong impression on viewers, gaining much attention from the young generation.

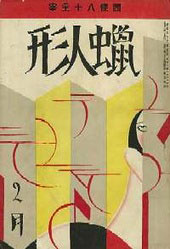

In November 1905, Yumeji Takehisa started his career as a painter at the age of 22 after submitting an illustration piece to the magazine "Chugaku Sekai (the Middle School World)". At a time when nihonga painters were dominating the field of book illustration, Takehisa's work dealing with everyday motifs left a strong impression on viewers, gaining much attention from the young generation.From the mid-Meiji through Taisho period, when the publication of magazines expanded along with the development of printing technology, Takehisa flourished as the foremost book illustrator of the time, working for over 2200 volumes of 180 magazines. By the end of the Taisho period, when the issue of "art and the masses" came to the fore, he devoted himself to the creation of innovative graphic design in the field of "commercial art", widening his appeal as an artist.

This exhibition traces the career of this prolific artist, with focus on his magazine illustrations and graphic designs.

Celebrating the 125th anniversary of his birth, this exhibition reexamines Yumeji's oeuvre from various perspectives, while also introducing the "real" Yumeji through the presentation of his previously unexhibited work.

"The 125th Anniversary -Unknown Yumeji Takehisa" Exhibition - Takehisa Yumeji Museum

From 2009-07-03 To 2009-09-27Source: Tokyo Artbeat website http://www.tokyoartbeat.com/event/2009/2990.en

This year marks the 125th anniversary of the birth of Yumeji Takehisa(1884-1934). From the Meiji through to the Showa period, Yumeji rushedthrough 49 years of his life, making an imprint on the cultural realmas both painter and poet.

While Yumeji harnessed his talent as an artist, it's said that he wasalso busy with his romantic life, and that he traveled to many placesand lived a cosmopolitan life. Since his passing, Yumeji has beenintroduced in various ways through exhibitions and books. However,there are still many previously unexhibited works and unknown sides tothis singular figure, a source of unending fascination for his audience.

"Yumeji Bound Books -the Bound Book History of Modern Japan" Exhibition

From 2009-10-01 To 2009-12-23

Takehisa Yumeji Museum

Source: Tokyo Artbeat website http://www.tokyoartbeat.com/event/2009/AD96

| This year marks the 125th anniversary of the birth of Yumeji Takehisa, as well as the 100th anniversary of the launch of "Yumeji Art Collection -Spring Edition" that he published for the first time at the age of 25. The book soon became a bestseller, bringing much fame to this emerging painter. This exhibition showcases a total of 57 books that Yumeji wrote and numerous bound books that he produced. These books also shed light on his relationships with notable figures like print artist Koshiro Onchi, poet Yu Yoshii, writers Masao Kume and Mikihiko Nagata, and many others. Also on view are beautifully bound books and original illustrations that represent the history of modern bookbinding in Japan. |

"Yumeji Takehisa -the World of Performing Arts II"

From 2008-10-02 To 2008-12-23Source: Tokyo Artbeat website http://www.tokyoartbeat.com/event/2008/0DAE.en

| Takehisa's hometown of Honjo village, Oku county in Okayama prefecture was a shukubamachi (post station) where the performing arts had long flourished. Born into a family of art lovers and growing up in a village where performing artists like Echigo lion dancers and joruri puppeteers came and went incessantly, Takehisa nurtured his own interest in Japanese traditional arts. Some of his work reflects his extensive study of and fascination with this particular genre. Takehisa experienced not only traditional Japanese arts such as joruri and kabuki, which he saw in his childhood, but also western plays performed at the Geijutsu-za, whose sponsor Hogetsu Shimamura was also his former teacher at Waseda. He also took inspiration for his work from the theatrical designs for children's plays written by Ujaku Akita. Takehisa also showed a strong interest in new forms of entertainment: cinema, as well as Ballets Russes (Russian Ballet) which created a worldwide sensation at the time. |