Prints in Collection

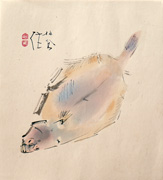

Seihō's Guide to Drawing

Seiho's Guide to Drawing Volume 1, 1901 IHL Cat. #783 | Seiho's Guide to Drawing Volume 2, 1901 IHL Cat.#784 | Seiho's Guide to Drawing Volume 3, 1901 IHL Cat. #2225 |

Seihō's Album of the Twelve Calendrical Animals

| Tiger from Seihō's Album of the Twelve Calendrical Animals, 1903 IHL Cat. #1576 | IHL Cat. #2293 | c. 1900-1915 IHL Cat. #920 |

Twelve Calendrical Animals, originally c. 1900-1915, this edition c. 1930s-1940s IHL Cat. #867 | -intentionally left blank- | -intentionally left blank- |

Scenes of China

from the portfolio Scenes of China, 1936

IHL Cat. #2458.01

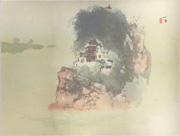

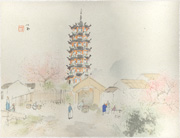

Longhua Temple, Jiangnan

from the portfolio Scenes of China, 1936

IHL Cat. #2458.02

West Lake, Hangzhou (Duan Bridge) from the portfolio Scenes of China, 1936

IHL Cat. #2458.03

from the portfolio Scenes of China, 1936

IHL Cat. #2458.04

View of the Yangtze River

from the portfolio Scenes of China, 1936

IHL Cat. #2458.05

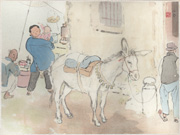

Sūzhōu Street

from the portfolio Scenes of China, 1936

IHL Cat. #2458.06

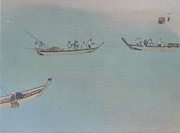

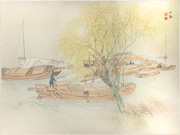

Zhenjiang, Boats at Anchor

from the portfolio Scenes of China, 1936

IHL Cat. #2458.07

Nanjing Gulou (Drum Tower)

from the portfolio Scenes of China, 1936

IHL Cat. #2458.08

Xiaogu Mountain

from the portfolio Scenes of China, 1936

IHL Cat. #2458.09

Yellow River (Huang He) Cave Dwellings from the portfolio Scenes of China, 1936

IHL Cat. #2458.10

from the portfolio Scenes of China, 1936

IHL Cat. #2458.11

Datong Ancient Temple

from the portfolio Scenes of China, 1936

IHL Cat. #2458.12

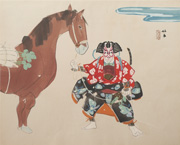

Seihō's Masterpieces

Puppy from the series Seihō's Masterpieces (set 1), 1938 IHL Cat. #914 |

| Winter Day in the Village from the series Seihō's Masterpieces (set 2), 1940 IHL Cat. #911 | River Breeze from the series Seiho's Masterpieces (set 2), 1940 IHL Cat. #843 |

| Grilled Sea Bream from the series Seihō's Masterpieces (set 2), 1941 IHL Cat. #910 | South China Scenery from the series Seihō's Masterpieces (set 2), 1942 IHL Cat. #2462 | -intentionally left blank- |

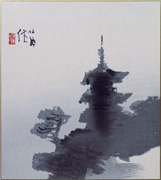

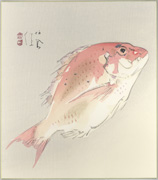

| Yanaka Pagoda in Moonlight, undated (posthumous after 1942) IHL Cat. #781 | Sea Bream, undated (after an c. 1930s ink on silk painting) IHL Cat. #2525 | -intentionally left blank- |

Fan Designs

Mount Fuji (folding fan design), undated

IHL Cat. #896

Fish, (folding fan design) undated

IHL Cat. #1577

Kakemono

Dried Persimmons, undated hanging scroll IHL Cat. #1025 |

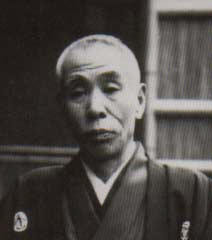

Biographical Data

ProfileTakeuchi Seihō 竹内栖鳳 (1864-1942) Takeuchi Seihō, a native son of Kyoto, was born during the turmoil towards the end of the Tokugawa Shogunate and the advent of the 1867 Meiji restoration. He was to become "the great Kyoto painter of his generation: prodigiously gifted, boundlessly curious, fearless, open, astute, articulate."1 As the "most celebrated practitioner" of the Maruyama-Shijō school of art, a realistic style of art dominant in the Edo period, he "enjoyed extraordinary fame during his lifetime..."2 He received traditional training in style and technique primarily from Shijō school painter and print designer Kōno Bairei (1844-1895). His talent was evident and he gained major commissions and public recognition at a young age. His fame continued to grow and in 1900 he was commissioned by the government to travel to Europe and study Western art. In Europe he was attracted to the Romantic masters, especially Turner and Corot, and their influence can be seen in the "lively synthesis of Western and Japanese styles" he created after his return.3 In 1937, towards the end of his career, he was awarded the prestigious Order of Cultural Merit a distinction that was to also be given to a number of his students, attesting to his prowess as a teacher. While primarily known as a painter, working with the Kyoto publisher Unsōdō, he created some of the most sumptuous print designs of the 20th century including the print series Twelve Animals of the Zodiac and a series of portfolios titled Seihō's Masterpieces completed just before his death in 1942 and called by Jack Hillier “one of the most magnificent printing achievements of the twentieth century.”4 1 Ehon: The Artist and the Book in Japan, Roger S. Keyes, The University of Washington Press with New York Public Library, December 2006, p. 252. 2 The Art of Modern Japan: From the Meiji Restoration to the Meiji Centennial 1868-1968, Hugo Munsterberg, Hacker Art Books, 1978, p. 46. 3 The Japanese Print Since 1900: Old dreams and newvisions, Lawrence Smith, British Museum Publications Ltd., 1983, p. 38. 4 The Art of the Japanese Book, Jack Hillier, Sothebys Publications, London, 1987, p. 93. |

Biography

Takeuchi Seihō (1864-1942) 竹内 栖鳳 (たけうち せいほう) and after 1901 written 竹内 恒吉

Early Life

Born Takeuchi Tsunekichi 竹内恒吉 on December 20, 1864 in one of Kyoto's textile districts, his parents ran a prosperous fish restaurant serving local craftsmen and the traffic generated by nearby Nijo Castle. As an only son who was too frail to work in the restaurant, he was doted upon, allowing him the freedom to pursue his own ambitions and pleasures.

He received his formal education at a local temple school with supplemental tutoring in Chinese literature. His early love of drawing was encouraged by the many textile designers who ate at his family's restaurant and at around the age of 13 he began studying the fundamentals of brush painting with Tsuchida Eirin, a distant relative and textile designer who lived nearby.

Training with Leading Shijō School Artist Advances Career

At the age of 17 he had exhausted his first teacher's knowledge and was sent to study with Kōno Bairei (1844-1895), a Shijō school painter and print designer and one of the foremost artists of his day. Bairei's status provided his students entry to professional painting circles and Seihō's talent quickly made him a Bairei favorite, who was to quickly confer upon him the title "Chief of Crafts"1 and, later, the artist name (gō) Seihō [ (meaning "a place where the phoenix lives."2) In 1883 Bairei secured Seihō a minor position at the Kyoto Prefecture Painting School (Kyoto-fu-Gagakkō). It was during this period at the School that his submitted work to exhibitions and fairs brought him to public notice.

In 1887, Seihō married Takayama Nami the adopted daughter of a prosperous merchant and left Bairei's studio to become an independent artist.3 Seihō's departure was brought on, at least in part, by his desire to break from Bairei's insistence "that his pupils master the Shijō-School colloquial before they try variations prompted by direct study of nature."4

Moving into a house built by his father across from the family restaurant, "Seihō was to spend the major, and most productive, portion of his career living there..."5 The house served as both studio and atelier for him.

Seihō was to have seven children with Nami after fathering two children with his family's domestic, a not unusual occurrence for "the pampered youth of that period."6 He was also to father a number of children with his devoted student Kihō, with whom he had a life-long relationship.

Through contacts and his own talent, Seihō quickly gained commissions for textile designs from prosperous textile companies, most prominently the Takashimaya Company 高島屋. The success of his textile designs led to commissions for paintings that were displayed at major nihonga 日本画(Japanese-style painting) exhibitions, winning acclaim for both the artist and his sponsors.

In 1888, with the encouragement of Ernest Fenollosa, he established the Kyoto Young Artists' Institute.7 In 1895, he became an instructor at the Kyoto Municipal School of Arts and Crafts (Kyoto Shiritsu Bijutsu Kōgei Gakkō; formerly the Kyoto Prefectural School of Painting).

A Turning Point - Travel to Europe and Romanticism

In 1900, Seihō was commissioned by the Ministry of Agriculture and Trade and the City of Kyoto to attend the Fifth International Exposition for Art and Industry in Paris "to inspect the situation of the art world in major European cities, and to collect materials for art education."8 For six months Seihō traveled through Europe visiting over 20 cities and almost every zoo, sketching animals from life, and studying, in particular, the Romantic artists. In Joseph Mallord William Turner (1775-1851) and Camille Corot (1796-1895) he discovered "a mode of expression... [having] many points in common with Oriental painting."9

While his European trip provided Seihō with the opportunity to see the actual paintings of the Romanticists, his attraction to Romanticism had its roots in his admiration for the work of the Japanese artist Kishi Chikudō (1826-1897), who created Romanticism's "Japanese equivalent."10 Seihō learned from Chikudō's work "to draw his motives directly from nature."11

After returning from Europe, Seihō explored the possibilities of a new naturalism with Japanese overtones. He wrote:

| While in Europe, I exchanged opinions with two or three painters, and it did not seem to me that there was much difference between what Europeans see and what we see. In the past the painting methods of Orient and Occident have been different, but one cannot overlook a certain spiritual link. Even in the subjective painting of the Orient, one cannot paint the true nature of something until one understands its actual form. The first step, therefore, is to learn the basic organization of form. After that, it is possible to grasp the overall meaning of things. In Japan today, however, what passes for subjective Oriental painting is a matter of copying old styles; the brush moves along by habit, and there is concern only for rules. It happens that in our times both the Orient and the Occident are concerned with subjective painting, but the Western painters are proceeding along a fundamentally sound path, while Japanese painters are blindly following the rules that have been inherited, without examining the fundamental causes and effects. If Japanese painting is to develop, we must make up for our short points by adopting the better features of European painting."12 |

Seihō's post-Europe adoption of "the better features of European painting" blended with traditional Japanese techniques led to depictions of animals and landscapes that "stunned the public."13 So taken was the public with his pictures of animals, that it was said, "Seihō can understand even what sparrows are saying.”14

Upon his return, Seihō reinforced his self-described "spiritual link" with Occidental painting by altering the manner in which he wrote his name, using the characters meaning "west" (a phonetic for sei).15

Lion (shishi 獅子), 1901-1902

Tokyo Fuji Art Museum

Note: A result of Seihō's long hours in European zoos

Tokyo Fuji Art Museum

Note: A result of Seihō's long hours in European zoos

An Interesting Anecdote

Source: "Takeuchi Seihō: Painter of Post-Meji Japan," Wallace S. Baldinger, The Art Bulletin, Vol. 36, No. 1, College Art Association, 1954

In an interesting anecdote about Seihō's desire to follow the European "principle of working directly from the object", Baldinger describes Seihō's approach to a 1910 commission by the Abbot of Higashi Honganji to create a ceiling mural of flying Buddhist angels for the Main Gate of his temple.

| He hired a model to pose nude, sometimes even suspended as though flying... As the days grew cooler the hibachi provided in Japanese fashion as the sole source of warmth inside became increasingly inadequate for a model posing nude. Long before the drapery stage was reached in the preparation of the cartoons, the model excused herself for a week-end trip to Tokyo and failed to return. Seihō persuaded another girl to pose, but the exposure was likewise too severe. She sickened and died. The story circulated...that the painter was robbing his models of their breath of life in order to incorporate it in his pictures. Every prospective model approached for the third attempt naturally refused - until at length Seihō found in the Gion Geisha District near his home a maiko who declared that even if she too were to die she could not forego the honor of posing for the master. The preliminary studies in the nude were almost completed when the maiko contracted pneumonia; anxious to see the studies finished before giving up, she continued to pose, and died of pneumonia as at least one of her predecessors had. After this, no girl would go near the shed at Higashi Honganji. |

Without models, Seihō refused to finish the work and the ceiling remained unpainted.

Woodblock Books and Prints

While not a print maker per se, the popularity of his paintings created a market for their reproduction in print form.

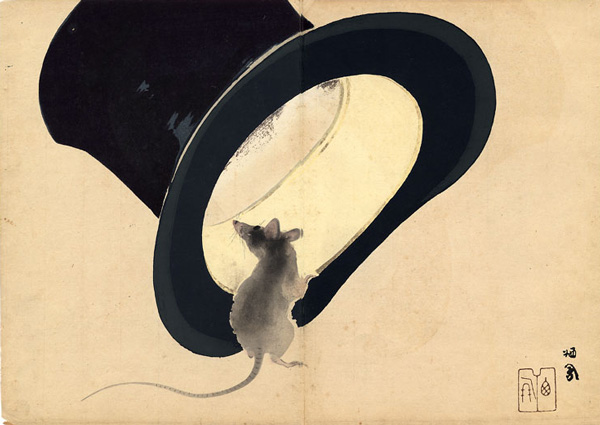

| Mouse and Top Hat, 1912 37.4 x 47.6 cm |

In 1901, working with the Kyoto-based publishing house Unsōdō, he created 4 volumes of gafu (picture albums) titled Seihō's Practice Painting Album (Seihō shūgachō), three volumes of which are in this collection. Lawrence Smith states that these volumes, "stand at the end of a tradition over a century old of gafu, consisting of woodblock reproductions of a specific artist's work and styles."16

Seihō's long association with Unsōdō continually enhanced his reputation, with print series such as Seihō's Twelve Views of Mount Fuji (Seihō jūni Fuji), 1894; Seihō's Album of the Twelve Signs of the Zodiac (Seihō-ga Haku hitsu jūnishi jo) 1900-1915; and his ultimate series of prints issued in intervals from April 1937 to November 1942, the sixty-six print opus, Seihō's Masterworks (Seihō ippin shū.)

Setting Fashion

Starting in 1907, after the institution of the Bunten (Ministry of Education exhibitions), Seihō was active as a both a judge, representing artists in Kyoto, and as a participant, winning prizes for many of his own works. At the behest of the Kyoto government, he worked to keep the major Kyoto painters united, allowing them to gain "leverage over the more numerous and divisive Tokyo cliques in national exhibitions."17 His "art and influence as a judge in government exhibitions was not just revered; it set fashions."18

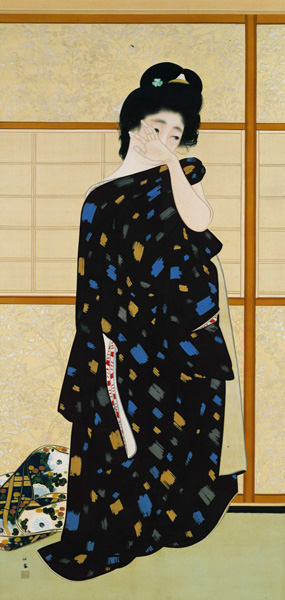

| Posing for the First Time (絵になる最初), 1913 183.2 × 87.5 cm | Seihō's 1913 painting Posing for the First Time (1913), exhibited in the 7th Bunten, "quickly gained notoriety for its suggestion of nakedness, the nude making infrequent appearance in nihonga. The kimono design that the sheepish model hides behind was subsequently worked up by the well-known department store Takashimaya in a brocade obi and named Seihō Kasuri — all the rage for the winter of 1914."19 In 2016 this painting was designated an important cultural property. In 1913 Seihō was made an Imperial Household Artist (teishitsu gigeiin) and was commissioned by the Imperial Household Agency to produce a pair of screens commemorating the coronation of the Taishō Emperor. In 1919 he was appointed to the Teikoku Geijutsu-in (Imperial Academy of Art.)20 As his artistic fame grew, so did his social status. "City officials brought their most honored native and foreign guests to visit their distinguished painter... [S]tatesmen and nobility called on him and vied to collect his works. Many foreign artists visited him, and a few became his students, including several women."21 While the artist never returned to Europe, in 1922 a painting of his was exhibited at the "Japanese Art Exhibition" held at the Salon of the National Art Association in Paris and he was recommended for membership in the Salon. In 1924, he was awarded the order of Chevalier de la Legion d'Honneur.22 |

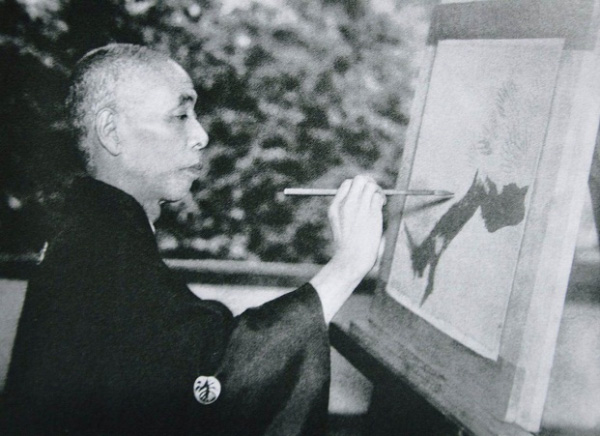

An undated photo of the artist at his easel

A Second Turning Point

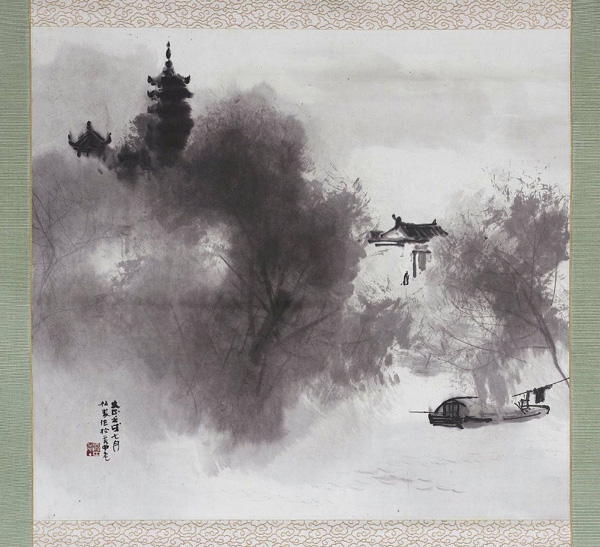

In the early 1920s, Seihō made two trips to China where he sketched extensively. Munsterberg states that from his China experiences Seihō "began working in a softer ink style based on Chinese painting of the late Sung period.." as can be seen in the below detail of his 1922 composition Chinese Landscape.23 Baldinger credits Seihō's China trip with adding a "new abstraction" to his work, stating that "the trips to China liberated him from enslavement to the object, set him back on the traditional Oriental road of ellipsis, understatement, reduction to essentials.24

Chinese Landscape 水墨山水, 1922

Hanging scroll; ink on paper

Image: 44.1 x 48 cm (17 3/8 x 18 7/8 in.)

Museum of Fine Arts, Boston Accession number: 40.725

Hanging scroll; ink on paper

Image: 44.1 x 48 cm (17 3/8 x 18 7/8 in.)

Museum of Fine Arts, Boston Accession number: 40.725

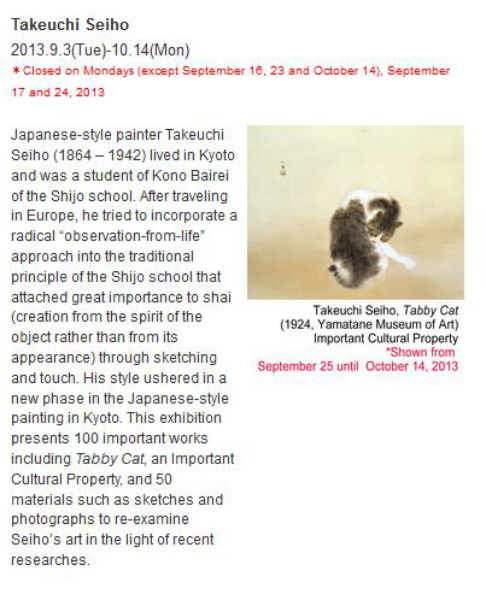

With the growing influence of contemporary French painting in Japan, a new movement formed among a younger generation of painters called Shinga or "New Painting." In November 1924 an exhibition of Shinga was held, with Seihō contributing a work titled Hambyō (A Kind of Cat) which garnered particular attention and which Baldinger describes as "approaching the exotic schemes of Toulouse-Lautrec" in its coloration.25

Hambyō (A Kind of Cat)*, 1924

Kakemono, color on silk, 32 3/4 x 40 1/4 in.

Yamatane Museum of Art

(An Important Cultural Property)

Kakemono, color on silk, 32 3/4 x 40 1/4 in.

Yamatane Museum of Art

(An Important Cultural Property)

*also known as Tabby Cat

"In order to do this work, Seihō sought for and found a cat to his liking and observed it for many days.

The vivid depiction is the result of these intimate observations."26

Despite suffering from frequent bouts of pneumonia and flu, Seihō continued to work productively throughout the 1930s, creating in the period 1937-1942 his print opus titled Seihō's Masterpieces (Seihō's ippin shū), working in conjunction with the Kyoto publisher Unsōdō. (See the article Takeuchi Seihō: Seihō's Masterpieces for images of the sixty-six prints making up this series.)

On April 28, 1937, Seihō, along with his rival Yokoyama Taikan (1868-1958), was awarded the Order of Cultural Merit for Japanese style painting (nihonga).27

When I stand in front of Seihō's painting, I find myself always exclaiming 'umai' (absolutely superb) and marvel at it from the bottom of my heart.

In the case of Taikan's painting, I am moved by the vigor of his spirit but

seldom compelled to utter 'umai'.28

- Kaburaki Kiyokata (master 20th-century nihonga painter and illustrator)

The Artist's Passing

Seihō's last years were spent in Yugawara, a hot-springs town. (Seihō was to use a seal on his work that read "Seihō at a hot spring inn" for some work during this period.) Such was Seihō's fame that while dying of pneumonia at the age of 78, the mayor dispatched a fire truck and ambulance in search of an oxygen tank to ease his suffering.29 Such was his fame that for years after his death on August 23, 1942 citizens commemorated his passing with prayers and ceremonies.30

Teaching and Students

A major part of Takeuchi Seihō's legacy were the many students who went on to achieve fame, including ten who went on to be awarded the Order of Cultural Merit. He taught at the Kyoto Municipal School of Arts for over 30 years, and at his own studio, formed in 1903, which he named Chikujōkai (Bamboo Stick Fellowship), he trained well over 100 students.

Starting with his first student, his cousin Hashimoto Shinnosuke (1873-?), artists such as Hashimoto Kansetsu (1883-1945)31, Nishiyama Suishō (1879-1958), Tsuchida Bakusen (1887-1936), Nishimura Goun (1877-1938), Uemura Shōen (1875-1949), Tokuoka Shinsen (1896-1972), Tsuji Kakō (1871-1931), Miki Suizan (1887-1957) and Ito Takashi (1894-1982) came under his tutelage.

He supported his students when they formed the Kokuga Sosaku Kyokai (National Creative Painting Society) which, "for a time raised the standard against Bunten."32 He encouraged his students, in the words of Lawrence Smith, "to express their individuality and was opposed throughout his life to the increasing formalization of Nihonga and its domination by official exhibitions."33

"Seihō honed the skills and guided the careers of countless artists and artisans of the succeeding generation - for an unmatched impact on the modern Kyoto art world."34

Recent Exhibitions

The National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo

Born in Kyoto and having studied under Kono Bairei, Takeuchi Seiho (1964–1942) influenced many younger painters including Tsuchida Bakusen as a leading modernizer of the traditional Kyoto style.

While actively incorporating techniques of other schools, Seiho tried to break with old habits in the painting circle by refusing to formally inherit stereotyped motifs and related techniques. Behind his attempts were his travels in Europe to observe the 1900 Exposition Universelle in Paris. Having been exposed to numerous works of art in Europe, the painter realized the importance of careful observation from life. However, Seiho’s vision was so broad that he did not introduce Western techniques blindly. Founded in Kyoto in the middle of the Edo period (1600–1868), the Maruyama school attached importance to naturalistic observation. The subsequent Shijo school was characterized by tastefulness with witty and refined brushwork. In the last days of the Tokugawa shogunate, however, these styles became more and more formalistic, leaving nothing but stereotyped motifs and techniques to draw them. Building upon the Western technique of observing from life, Seiho tried to unearth the original ideals of the Kyoto tradition in a spirited attempt to create art standing shoulder to shoulder with its Western counterpart.

Presenting 110 pieces including Seiho’s masterpieces, important works and those shown publicly for the first time, together with 60 materials including his sketches, this exhibition provides an overview on the painter’s art to illustrate the foundations of the modern history of Japanese art laid by Seiho.

About the Sections

1. Starting Out as an Artist, 1882-1891Takeuchi Seiho became a pupil of the Shijo school nihonga artist Kono Bairei (1844-1895), under whose strict discipline, in addition to Shijo-style painting techniques, he also acquired a grounding in Chinese classics and so on. Outside the art school, he also traveled to the Hokuetsu region to do sketches with his master and kept on training by copying old paintings.

As if to demonstrate such studies, Seiho’s works during this period are composed of traditional subjects done in a traditional touch. Among them are styles unimaginable from Seiho’s later works, suggesting how remarkably his artistic career developed from his days as an apprentice to the advanced period.

In the background of such traditional painting and unexpected styles lay a tremendous number of copies of old paintings. The works Seiho copied were not only old paintings belonging to shrines and temples or private collectors but also reduced copies of old paintings done by his teacher Bairei which remained. Content-wise, in some cases, the original can be recognized at once, while, in other cases, it is hard to identify what Seiho copied. Moreover, it was not only works by the Shijo school, to which his teacher Bairei belonged, that he copied. Such wide-ranging studies of old paintings eventually gave rise to a subject of debate and proved an opportunity for Seiho to be spotlighted on as a topic of conversation within the art circles.

Meanwhile, another point that should not be overlooked is that the works are somewhat full of freshness. The atmosphere is different from a painting of the same old subject done automatically in the same old touch. In fact, while doing copies of old paintings, Seiho was habitually enthusiastic about sketching everyday nature such as flowers and birds. The sketches of creatures done during this period concentrate on accurate portrayal of the details so that the texture of even a bird’s feathers or the soft petals of a plant are depicted in fine lines of Sumi and rich coloring. The freshness identifiable in Seiho’s works is the fruit of these sketches. Sketching developed little by little in character and later became the crux of Seiho’s work.

In 1892 (Meiji 25), Seiho submitted Byoji Fuken (Cat with Kittens) to Kyotoshi Bijutsu Kogeihinten, an exhibition of arts and crafts held in Kyoto. This painting drew many people’s attention as the brushwork of several different schools such as the Maruyama school, the Shijo school, and the Kano school were employed in a single work and Seiho was referred to as “nue-ha (chimerical).” While on the one hand, he was condemned for breaking the conventional rule of painting by mixing different schools’ techniques together, on the other hand, his challenge was anticipated as a sign of the emergence of a new school.

During this period, Seiho worked on a variety of subjects including historical events, contemporary scenes of Kyoto, and skeletons. Among them were many examples indicating that he was clearly aware of the expressions in Western paintings. Seiho was conscious of the existence of Western art from a considerably early stage and held meetings where foreign art literature was read and discussed at his own art school. Furthermore, through also being involved in the artistic textile business in Kyoto, which was looking abroad in order to participate in the International Expositions and secure a foreign market, he deepened his thoughts on the state of Japanese art in Europe.

In 1900 (Meiji 33), Seiho went to Europe to visit the Exposition Universelle in Paris. Though it was a short trip, he came in touch with a lot of Western art in several places. As soon as he returned to Japan, Seiho painted lions and European landscapes in a Western painting-like realistic style, which attracted attention. However, what he came to emphasize most through his experiences in Europe was a blending of portrayal based on observation of the real thing, which was the strong point of Western art, and representation of the true nature of the subject rather than the external shape, which was a forte of traditional painting in Japan.

Seiho endeavored to reconsider the expressions in traditional painting with a broad field of vision aiming to be on a par with Western art. This idea also provided an impetus to the artists in Kyoto in those days. Seiho, who was one of the young artists in Kyoto that was interested in Western art, grew to become the driving force of the art circles with his eyes fixed on the world.

In this period, Seiho had already established a standing in the art circles as a teacher at the art school, proprietor of the private art school Chikujokai, where he had many pupils, and judge at the Bunten (Ministry of Education Fine Arts Exhibition), which began in 1907 (Meiji 40). Tsuchida Bakusen and other pupils also came to the fore and when they formed Kokuga Sosaku Kyokai in 1918 (Taisho 7), Seiho became advisor to that group.

Even though Seiho was now in a position watching over the efforts made by his juniors, he did not fail to eagerly study his own new expressions. For example, regarding the representation of animals, which he had always been good at, he was not satisfied at simply depicting the external shape or texture. He grasped the character of the individual animals such as their ferocity, the forcefulness of their movement, or their alertness towards human beings and tried to express such features in a momentary movement made by those animals.

As for landscape paintings, he created works that were neither the conventional tradition of representing hills and waters nor scenery expressions employing Western painting-like perspective, which he had acquired after visiting Europe. Seiho traveled to China twice from 1920 (Taisho 9) and these trips triggered a deepening in his landscape paintings from the point of view of subject and that of sense of coloring.

It should not be overlooked that though for a brief time, he studied figure painting during this period. He tried to reveal the form-wise most beautiful instant of a person from a sequence of movements, to capture a person’s feelings in a momentary gesture, or represent a three-dimensional illusion of human figures on the two-dimensional plane of a ceiling in a building. The subjects were human figures, but to Seiho, they were more than figure paintings. Topics leading to expression in general were integrated in this series of studies.

In the Showa period, Seiho often became indisposed and in 1931 (Showa 6), he went to Yugawara for a change of air. Once he recovered his health, he worked even more enthusiastically than before by undertaking paintings for the walls and fusuma (sliding doors) of Higashi-Honganji. As Yugawara suited him, he moved his base there and continued painting until his death by coming and going between Yugawara and Kyoto.

During this period, Seiho captured his subject swiftly and accurately in a touch that had become all the more refined. Looking at his sketchbooks, unlike the detailed sketching of the subject he did in the old days, in many cases, the movement and volume of the subject are captured broadly in speedy lines. He also came to do numerous works in which his eyes were cast warmly on small animals living in accord with the changes of the seasons. Needless to say, he did not fail to continue research on expression and it is noteworthy that, even in his later years, he produced experimental works such as, for example, a case in which he represented the glow of the sunlight in gold leaf.

Seiho’s work consistently began from sketches based on observation of the real thing. However, upon detailed observation of his works, we notice that from when he began sketching to the actual painting, at each stage of production, he picked and chose a variety of elements and that the way he selected changed as he grew older. This change was no other than the transition of Seiho’s artistic style. In his later years, Seiho sometimes worked on a subject he had painted in his young days again. However, the expression was never the same as the old days. His volition to constantly capture the subject with a new eye and represent that in his picture was what gave him the strength to refuse adhering to a single expression and continue, even in his later years, opening up expressions rich in variety.

Yamatane Museum of Art

The 70th Memorial: Tribute to Takeuchi Seihō and His Fellows in Kyoto

29 September (Sat.) - 25 November (Sun.) 2012

The 70th Memorial: Tribute to Takeuchi Seihō and His Fellows in Kyoto

29 September (Sat.) - 25 November (Sun.) 2012

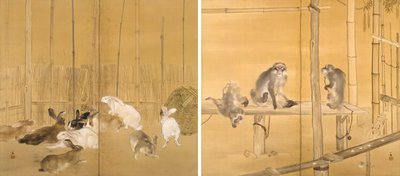

Takeuchi Seihō, Monkeys and Rabbits, National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo

Source: Yamatane Museum website http://www.yamatane-museum.jp/english/index.html

"Taikan in the east, Seihō in the west": Yokoyama Taikan and Takeuchi Seihō are inevitably included in any discussion of Nihonga or Japanese-style painting. The year 2012 is the 70th anniversary of the death of Seihō (1864-1942). This Kyoto-born artist quickly revealed his genius, becoming, by the time he was in his thirties, one of the leading painters in Kyoto art circles. His works elegantly capture the fleeting motions of living creatures and other aspects of the natural world and remain brilliantly fresh and captivating to this day.

In 1900, when the Exposition Universelle was held in Paris, Seihō toured Europe. Greatly stimulated by the experience of encountering Western art in its context, he created a new style that combined the Maruyama-Shijō school techniques of sketching from nature with aspects of Western art. His sophisticated sensitivity and superb brushwork enable him to address a variety of subjects, including animals, landscapes, and the human figure, in dedicatedly, energetically modernizing Nihonga.

This exhibition presents the works of Seihō as a leader of the modern Kyoto art world through the masterpieces he created from his early period to the final years of his life, including Monkeys and Rabbits, Posing for the First Time, Cockfighting, Tabby Cat (an Important Cultural Property), and Young Ducks.

We also focus on the historical development of the Kyoto art world, introducing Edo-period works, including paintings by Maruyama Ōkyo, the founder of the Maruyama school, a fount of creative inspiration for Seihō, and attempting to reveal the core DNA of the Maruyama-Shijō school during Japan's transition from the Edo to the modern period through the work of Seihō's students such as Uemura Shōen and Nishimura Goun.

_______________________________________________

Kyoto Municipal Museum of Art

"Masterpieces from the Permanent Collection: The Studio of Painter Takeuchi Seiho"

February - March 2009

"Masterpieces from the Permanent Collection: The Studio of Painter Takeuchi Seiho"

February - March 2009

How do painters discover themes and transform them into visual art? The essence of works by Takeuchi Seihō, one of the master painters in the collection, is revealed in this exhibition of his sketchbooks and rough drafts, which follow the various stages of the process through to the finished pictures.

_______________________________________________

A large collection of Seihō's works is held by the Kyoto Municipal Museum of Art

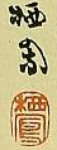

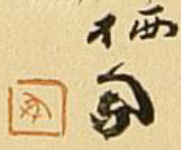

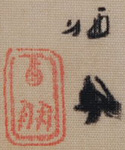

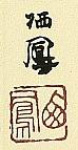

Signatures and Seals

Eric van den Ing reports that over 280 different seals as associated with Seihō and goes on to say I have been told that he actually used twice that number."34 A sampling of these seals along with the artist's various script signatures follows.

seal: unread signature: Seihō |  signature: Seihō |  signature: Seihō |  seal: unread seal: unreadsignature: Seihō |

seal: unread signature: Seihō |  seal: unread signature: Seihō |  signature: Seihō |  seal: unread seal: unreadsignature: Seihō |

seal: unread seal: unreadsignature: Seihō saku |  seal: unread signature: Seihō saku |  seal: unread signature: Seihō saku |  seal: unread seal: unreadsignature: Seihō |

seal: unread seal: unreadsignature: Seihō saku ? |  signature: Seiho Utsusu |  seal: Seihō signature: Seihō |  seal: unread seal: unreadsignature: Seihō |

seal: hō signature: Seihō |  seal: Seihō seal: Seihōsignature: Seihō |  seal: unread seal: unreadsignature: Seihō |  signed: Seihō Utsusu |  seal: Seihō signature: Seihō |

seal: unread seal: unreadsignature: Seihō saku |  seal: unread signature: Seihō |  seal: unread signature: Seihō |  seal: hō signature: Seihō |  seal: unread signature: Seihō |  seal: unread signature: Seihō |

signature: unread |  seal: unread seal: unreadsignature: unread |  seal: Seihō signature: unread |  signature: unread |  signature: unread |  signature: Seihō |

seal:unread |  seal: Seihō |

1 "Takeuchi Seihō: Painter of Post-Meiji Japan," Wallace S. Baldinger, The Art Bulletin, Vol. 36, No. 1, College Art Association, March 1954, p. 47.

2 "Western Japan's eclectic master," Matthew Larking, The Japan Times, February 6, 2009.

3 There are conflicting accounts of just how long Seihō stayed at Bairei's studio. Eric van den Ing reports in his article "One of Seihō's Lions," that Seihō "chose to attend the Kyoto Prefectural School of Painting between 1884-87, where he studied Kanō and Northern Chinese painting under Suzuki Hyakunen..." and that after his attendance "he returned to Bairei's studio and stayed there as his best student until Bairei died in 1895." Conant states "In August 1887, he used the occasion of his marriage to secure Baire's permission to become an independent artist." I've taken this to mean that he left Bairei's studio.

4 op. cit., Baldinger, p. 48.

5 "Cut from Kyoto Cloth: Takeuchi Seiho and His Artistic Milieu," Ellen P. Conant, Impressions The Journal of the Japanese Art Society of America, Number 33, 2012, p. 79.

6 For a fuller account of Seihō's love life see Ellen P. Conant's "Cut from Kyoto Cloth: Takeuchi Seiho and His Artistic Milieu," appearing Impressions The Journal of the Japanese Art Society of America, Number 33 2012, p. 71-93.

7 Guide to Modern Japanese Woodblock Prints: 1900-1975, Helen Merritt, University of Hawaii Press, 1992, p. 147. Note: As the Kyoto Young Artists' Institute, I have found no other mention of it and I wonder if it is being confused by Merritt with the Kyoto Young Painters Study Group founded in 1886. For more info on this group see Conant's article "Cut from Kyoto Cloth" footnote 9, p. 90.

In addition, the extent of the contact between Seihō and Fenollosa is unclear. I have only found a few references to their having crossed paths. One is to a 22 year old Seihō attending a Fenallosa lecture and another, a diary entrance of Mrs. Fenollosa, to the Fenollosa's purchase of two Seihō sketches at Takashimaya. I also have not found any other reference to the Kyoto Young Artists' Institute.

8 "One of Seiho's Lions," Eric van den Ing, Andon 61, Society for Japanese Arts, Leiden, 1999 p. 5.

9 Modern Currents in Japanese Art, Michiaki Kawakita, Weatherhill/Heibonsha, 1974, p. 92.

10 op. cit., Baldinger, p. 50.

11 op. cit., Baldinger, p. 50.

12 op. cit., Kawakita, p. 92.

13 op. cit. Larking.

14 "Seiho of the West", Mariko Okada, Chanintr Living, Spring 2011, p. 11.

15 Biographical Dictionary of Japanese Art, Yutaka Tazawa, Kodansha International, Ltd. in collaboration with the International Society for Educational Information, Inc., 1981, p. 250.

16 The Japanese Print Since 1900: Old dreams and newvisions, Lawrence Smith, British Museum Publications Ltd., 1983, p. 38.

17 op. cit., van den Ing, p. 90.

18 op. cit., Larking.

19 ibid.

20 op. cit., Tazawa, p. 250.

21 op. cit., van den Ing, p. 90.

22 op. cit., Okada, p. 11.

23 The Art of Modern Japan: From the Meiji Restoration to the Meiji Centennial 1868-1968, Hugo Munsterberg, Hacker Art Books, 1978, p. 46.

24 op. cit., Baldinger p. 54.

25 ibid., p. 55.

26 Contemporary Japanese-Style Painting, Tanio Nakamura, Tudor Publishing Company, 1969, p. 35.

27 The Order of Culture, based on the Government Ordinance on the Order of Culture issued in February 1937, is a national honor awarded to those persons with outstanding contributions to the advancement of culture.

28 Nihonga Transcending the Past: Japanese-Style Painting, 1868-1968, Ellen P. Conant, The Saint Louis Art Museum, 1995, p. 323.

29 op. cit., Baldinger, p. 45.

30 ibid.

31 Kansetsu Hashimoto is reported to have said that he "didn't gain anything from being in Seihō's school," and the two remained in conflict and competition throughout their careers. ["Looking Back as Japan Advanced...," Matthew Larking, The Japan Times, January 16, 2009]

32 op. cit., Tazawa.

33 op. cit., Connant, p. 73.

34 Nihonga: Traditional Japanese Painting 1900-1940, Lawrence Smith, British Museum Press, 1991, p. 80.

35 op. cit., van den Ing, p. 13.

.jpg)

Drum Tower pr-fabefcdce05b7c4a.jpg)