| Readings: |

Tycho Brahe Galileo and Newton Gravity |

Tycho Brahe:

Tycho Brahe (1580's) was astronomy's 1st true observer. He built the Danish Observatory (using sextant's since telescopes had not been invented yet) from which he measured positions of planets and stars to the highest degree of accuracy for that time period (1st modern database). He showed that the Sun was much farther than the Moon from the Earth, using simple trigonometry of the angle between the Moon and the Sun at 1st Quarter.

The Earth's motion, as a simple matter of dynamics, was extremely perplexing to the medieval thinker. The size and mass of the Earth was approximately known since Eratosthenes had measured the circumference of the Earth (thus, the volume is known and one could simply multiple the volume with the mean density of rock to obtain a rough mass estimate). The force required to move the Earth seemed impossible to the average medieval natural philosopher.

Brahe had additional reason to question the motion of the Earth, for his excellent stellar positional observations continued to fail to detect any parallax. This lack of annual parallax implied that the celestial sphere was "immeasurably large". Brahe had also attempted to measure the size of stars, not understanding that the apparent size of a star simply reflects the blurring caused by the passage of starlight through the atmosphere. Brahe's estimate for the size of stars would place them larger than the current day estimate of the size of the Earth's orbit. Such "titanic" stars are absurd according to Brahe's understanding of stars at the time.

Copernican model Ptolemic model

Beyond Tycho Brahe's accomplishments in the observational arena, he is also remembered for introducing a compromise solution to the solar system model now referred to as the geoheliocentric models. Brahe was strongly influenced by the Egyptian idea of Mercury and Venus revolving around the Sun to explain the fact that their apparent motion across the sky never takes them more than a few tens of degrees from the Sun (called their greatest elongation). The behavior of inner worlds differs from the orbital behavior of the outer planets, which can be found at any place on the elliptic during their orbital cycle.

Egyptian model Tycho Brahe model

Brahe proposed a hybrid solution to the geocentric model which preserves the geocentric nature of the Earth at the center of the Universe, but placed the all planets in orbit around the Sun. This configuration resolves the problem of Mercury and Venus lack of large angular distances from the Sun, but saves the key criticism of the heliocentric model, that the Earth is not in motion. In other works, Brahe's geoheliocentric model fit the available data but followed the philosophical intuition of a non-moving Earth.

Neither the Egyptian or Tycho's models successfully predicts the motion of the planets. The solution will be discovered by a student of Tycho's, who finally resolves the heliocentric cosmology with the use of elliptical orbits.

Kepler:

Kepler (1600's) a student of Tycho who used Brahe's database to formulate the Laws of Planetary Motion which corrects the problems of epicycles in the heliocentric theory by using ellipses instead of circles for orbits of the planets.

Galileo:

Kepler's laws are a mathematical formulation of the solar system. But, is the solar system `really' composed of elliptical orbits, or is this just a computational trick and the `real' solar system is geocentric. Of course, the answer to questions of this nature is observation.

The pioneer of astronomical observation in a modern context is Galileo. Galileo (1620's) developed laws of motion (natural versus forced motion, rest versus uniform motion). Then, with a small refracting telescope (3-inches), destroyed the the idea of a "perfect", geocentric Universe with the following 5 discoveries:

spots on the Sun

mountains and "seas" (maria) on the Moon

Milky Way is made of lots of stars

Venus has phases

Jupiter has moons (Galilean moons: Io, Europa, Callisto, Ganymede)

Aristotelian Universe:

With the discoveries of Galileo, and the mathematical formulation of orbits by Kepler, a complete kinematic description of the solar system was accomplished. While this provided a very accurate predictor of the motions of the planets, and the size of the Solar System, it gave us no understanding of why the Universe is this way or what causes the planets to move (Newton will answer with gravity). Also, a solar system model does not address the question of the stars or what is beyond the stars.

Another key aspect of the Aristotelian Universe is that it was finite in size. The reasoning here is that the outer boundary of stars rotates around the Earth. If the heavens were infinite, and revolve in a circular path, then they would traverse an infinite distance in a finite time. By the same reasoning, straight lines must be an illusion since they can not be of infinite length or they would extend beyond the Universe. All lines are incomplete and imperfect, only circles are complete and therefore perfect.

In addition, an Aristotelian Universe is steady state, meaning that it has existed unchanging through eternity and its perfect motions had no beginning or end. This will be modified by the Church to allow for Creation and God as the First Cause.

Aristotle's Laws of Motion:

With Galileo's observations and Kepler's laws of Planetary Motion, the heliocentric models begins to dominant scientific thinking by the 17th century, despite its theology problems. However, this is a kinematic description of cosmology, a contains only information about positions and motion. What is missing from 17th century cosmology is a dynamical description of the Universe, i.e. one that includes the cause of motion. Rationalism requires a logical progress from cause to effect. Cosmology will also require some cause for the motion of planets and stars. But first, ancient cosmologists needed to get straight the idea of motion on the Earth. The first work in this area was done, of course, by Aristotle.

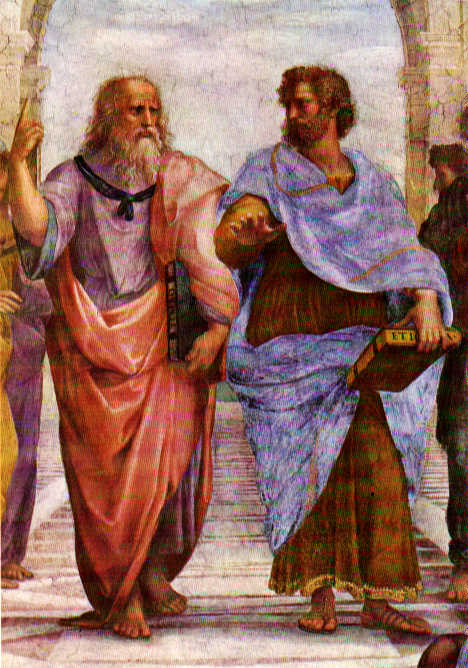

In the center of the `School of Athens' by Raphael are Aristotle and Plato, Aristotle's hand level to the Earth symbolizing his realism view of Nature; Plato's hand pointed towards the heaven symbolizing the mystical nature to his view of the Universe. This image symbols the sharp change in the meaning of how `natural philosophy' or physics will be done for the 2,200 years.

Aristotle stands in the Greek philosophical tradition which asserts that nature is understandable. This tradition, opposed to the idea that nature is under the control of capricious deities which are to be appeased rather than understood, is one of the roots of science.

Aristotle constructed his view of the Universe based on a intuitive feeling of holistic harmony. Central to this philosophy was the concept of teleology or final causation. He supposed that individual objects (e.g. a falling rock) and systems (e.g. the motion of the planets) subordinate their behavior to an overall plan or destiny. This was especially apparent in living systems where the component parts function in a cooperative way to achieve a final purpose or end product.

Aristotle also provides a good example of the way in which what one knows or believes influences the way one understands new information. His theory of motion flows from his understanding of matter as constituted of four elements: air, earth, fire, and water. Objects, being solid like earth, would tend to clump together with other solids (earth), so objects tend to fall to earth, their natural place. Thus, falling is a natural motion.

|

|

|

objects to fall on the Earth | fall to Earth |

The difficulty comes in thinking about horizontal motion. Making an object move usually has a pretty obvious cause. What's difficult is explaining why something continues in motion.

|

|

projectiles moved | "really" move |

Think of a spear being thrown. At first, it is not in motion, but then the thrower's arm provides an impetus which accelerates it (our vocabulary, not Aristotle's). But then, what keeps it going after it leaves the thrower's hand? It should fall to earth immediately since there's nothing obvious pushing it!

Aristotle's answer was that as the spear flies through the air, it leaves a vacuum behind it. Air rushing in pushes the spear forward until its natural motion (falling) eventually brings it to earth.

Aristotle also thought about the causes which start things moving. In the spear scenario, it's easy to say that the thrower's arm moves the spear, but what moves the thrower's arm? Aristotle said that another motion moved the arm (muscle contraction?) but he also realized that some earlier motion must cause the muscle to contract and that earlier motion must also have its own initiator.

To avoid the idea that there is an infinite chain of causes, Aristotle argued that there must be an "unmoved mover," something which can initiate motion without itself being set in motion. This view was preserved by medieval Church during the Dark Ages and became the ruling paradigm.

Galileo's laws of Motion:

Aside from his numerous inventions, Galileo also laid down the first accurate laws of motion for masses. Galileo realized that all bodies accelerate at the same rate regardless of their size or mass. Everyday experience tells you differently because a feather falls slower than a cannonball. Galileo's genius lay in spotting that the differences that occur in the everyday world are in incidental complication (in this case, air friction) and are irrelevant to the real underlying properties (that is, gravity). He was able to abstract from the complexity of real-life situations the simplicity of an idealized law of gravity.

Key among his investigations are:

Much of this thinking dealt with objects on the Earth. Galileo didn't extend his ideas to beyond the Earth's surface, that was for an astronomer named Kepler.

Newton:

Newton expanded on the work of Galileo to better define the relationship between energy and motion. In particular, he developed the following concepts:

Newton's laws of motion:

Example: You are trapped on a lake of ice with a sandbag. Remembering Newton's 3rd law, how do you escape?

Newton's Law of Universal Gravitation:

Galileo was the first to notice that objects are ``pulled'' towards the center of the Earth, but Newton showed that this same force (gravity) was responsible for the orbits of the planets in the Solar System.

Objects in the Universe attract each other with a force that varies directly as the product of their masses and inversely as the square of their distances

|

|

|