Bijinga Kuchi-e and Taishō-era Popular Magazines

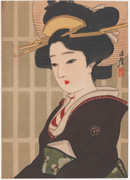

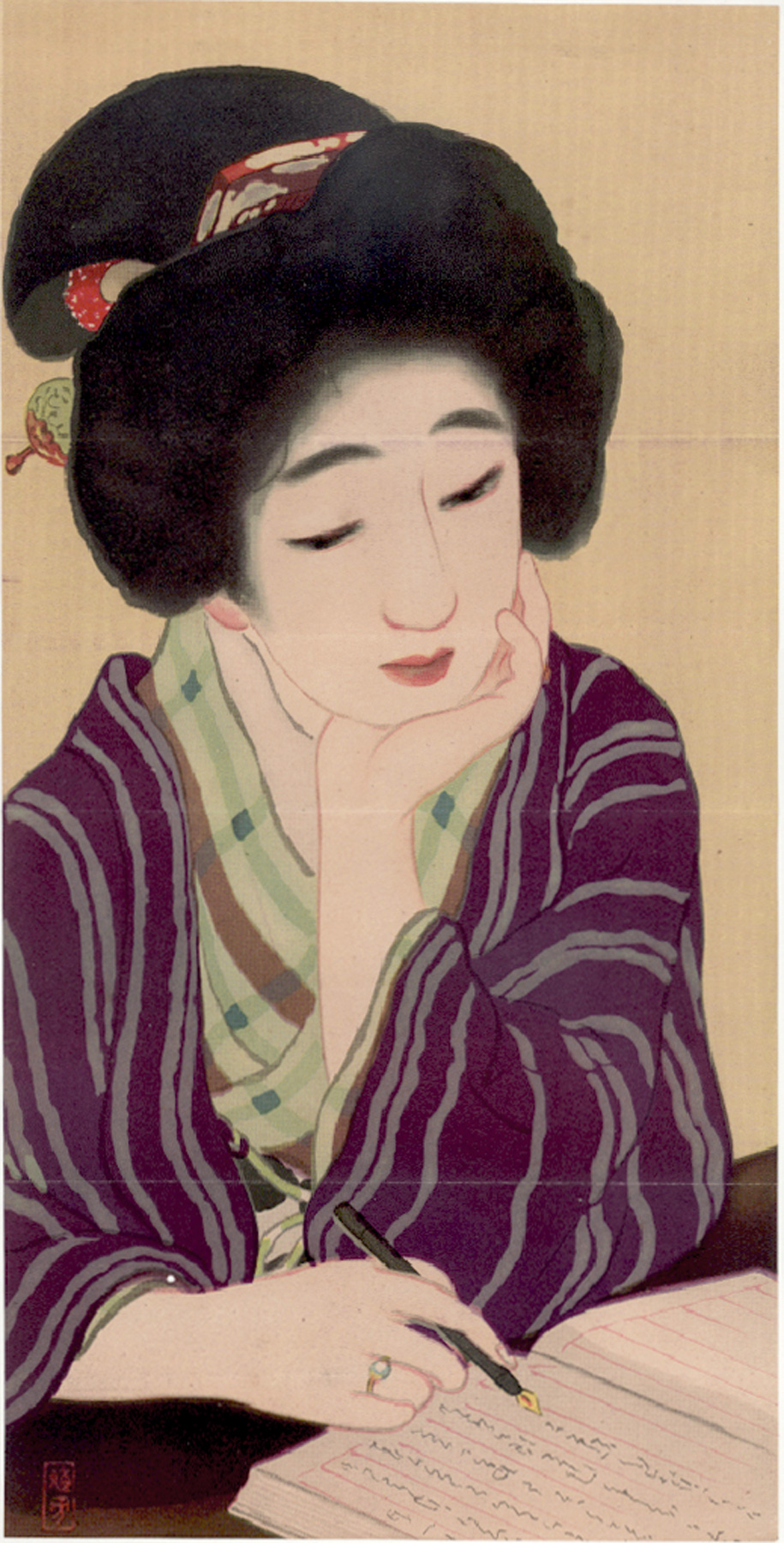

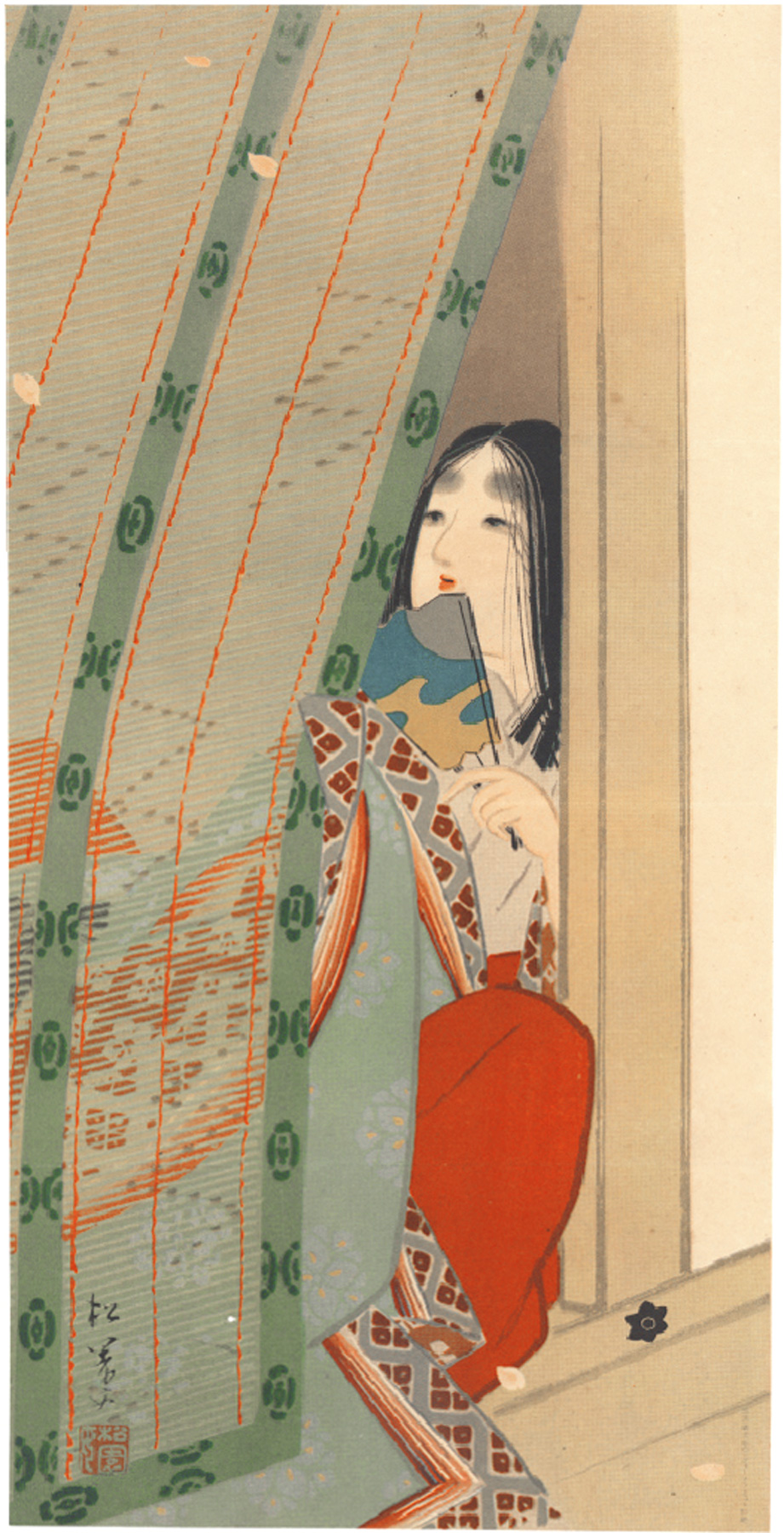

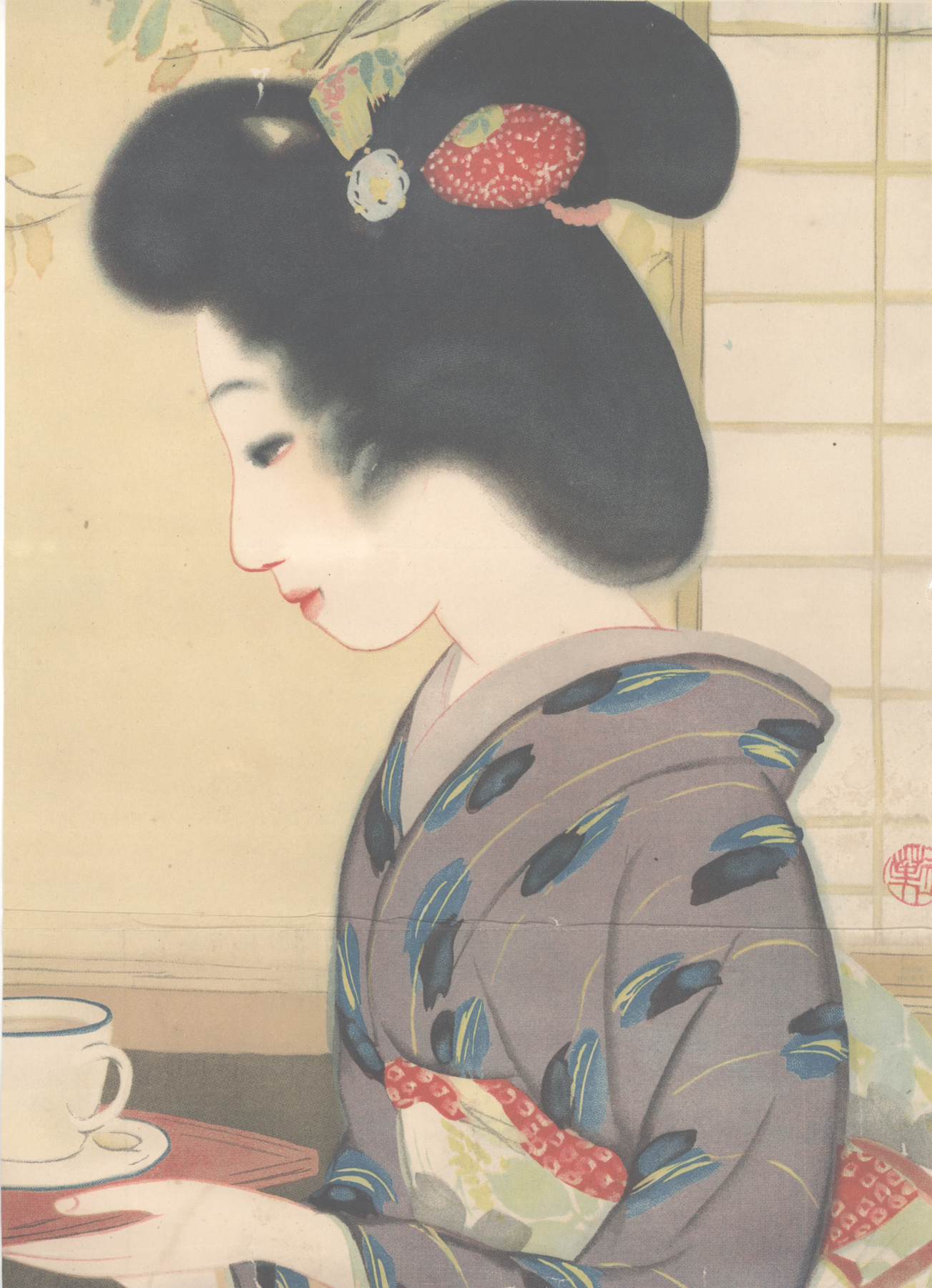

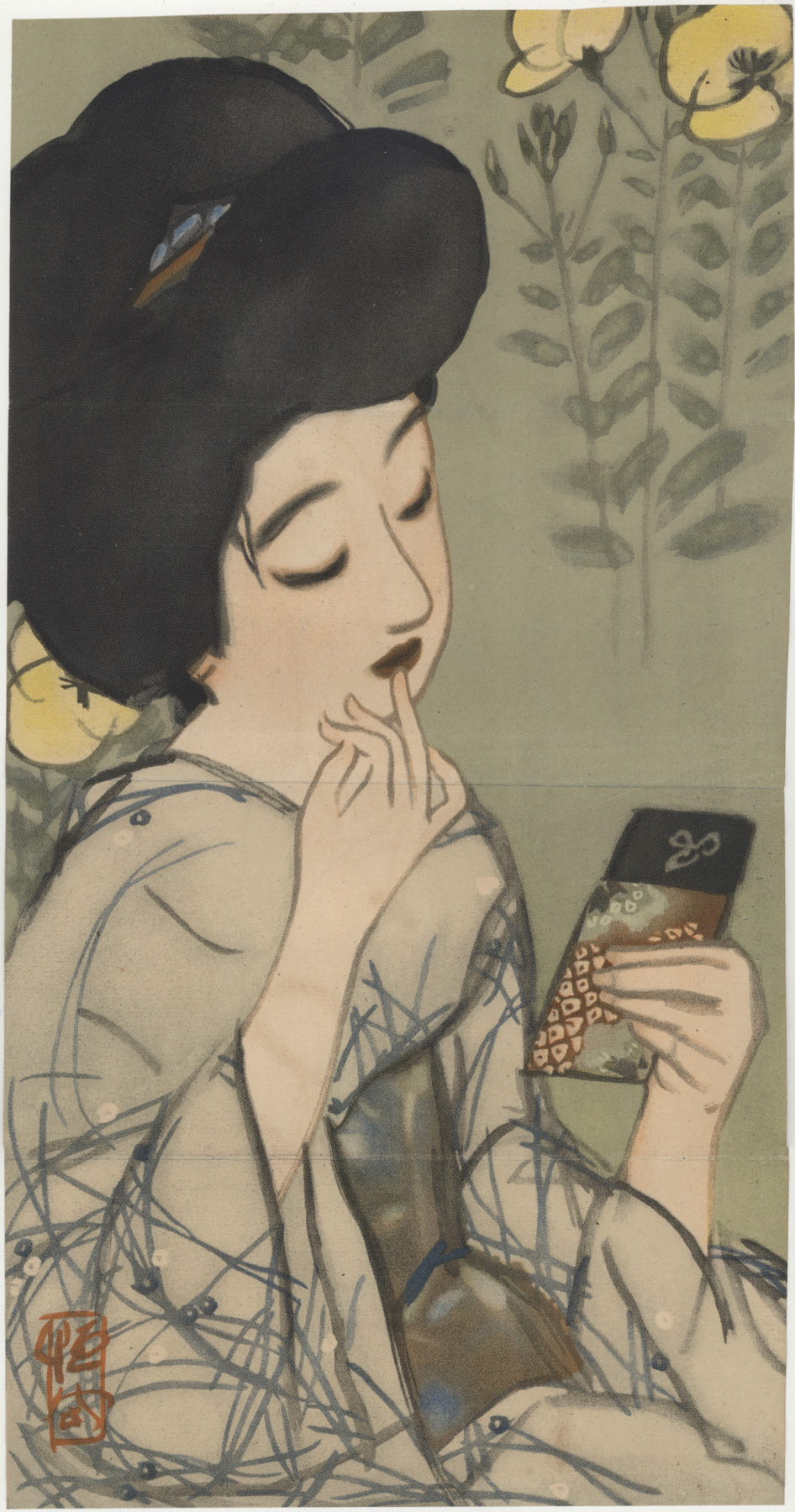

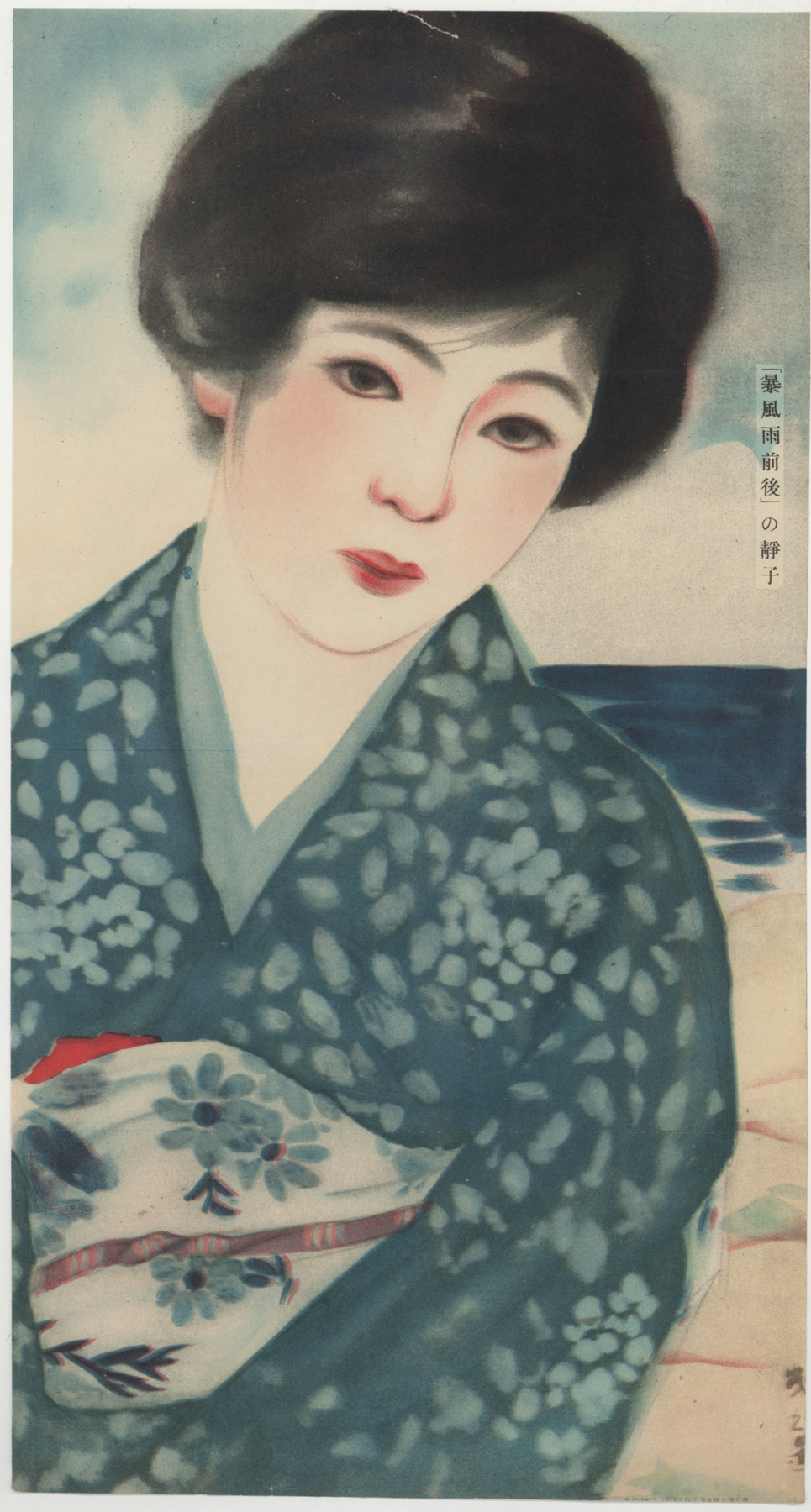

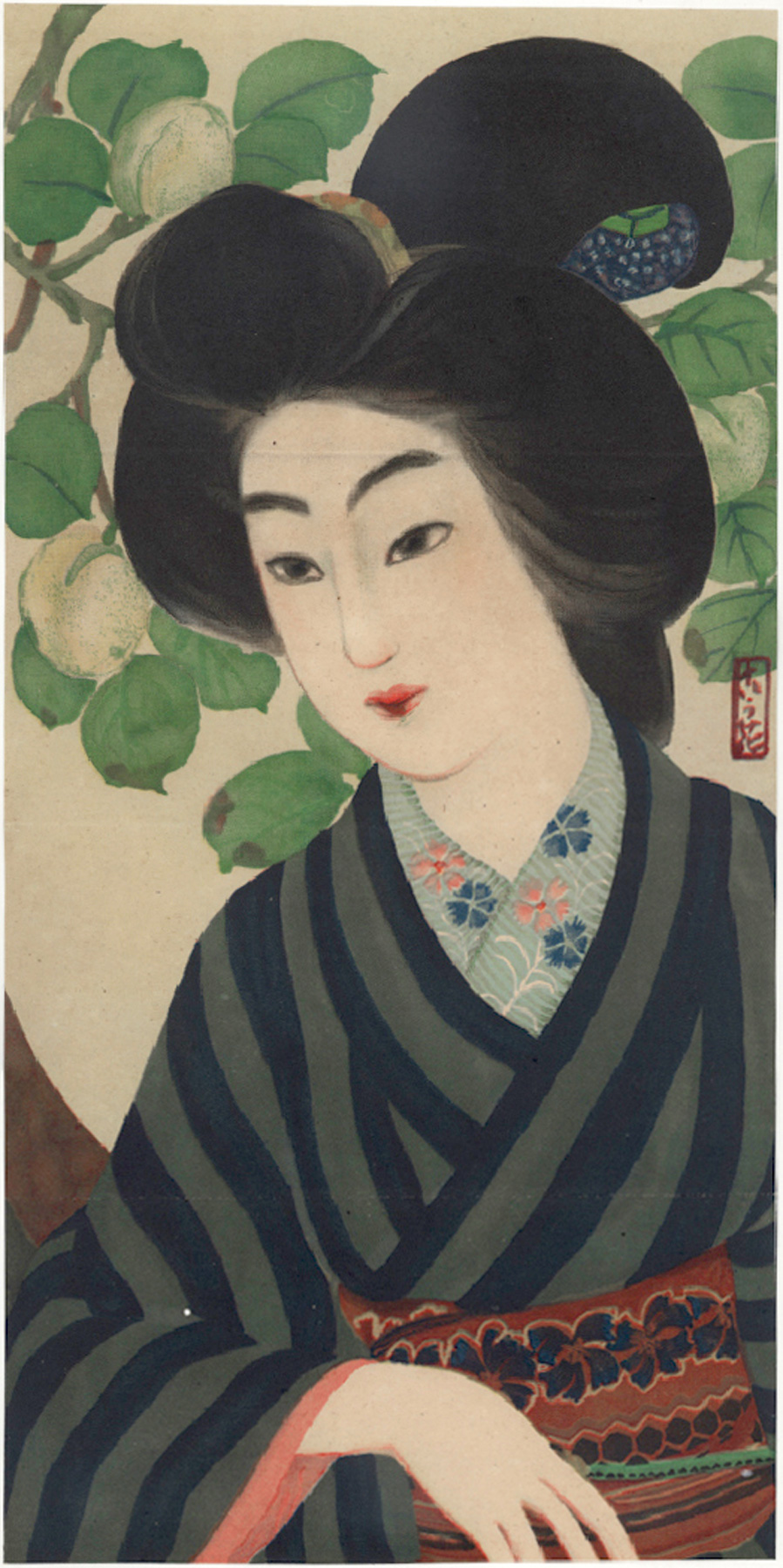

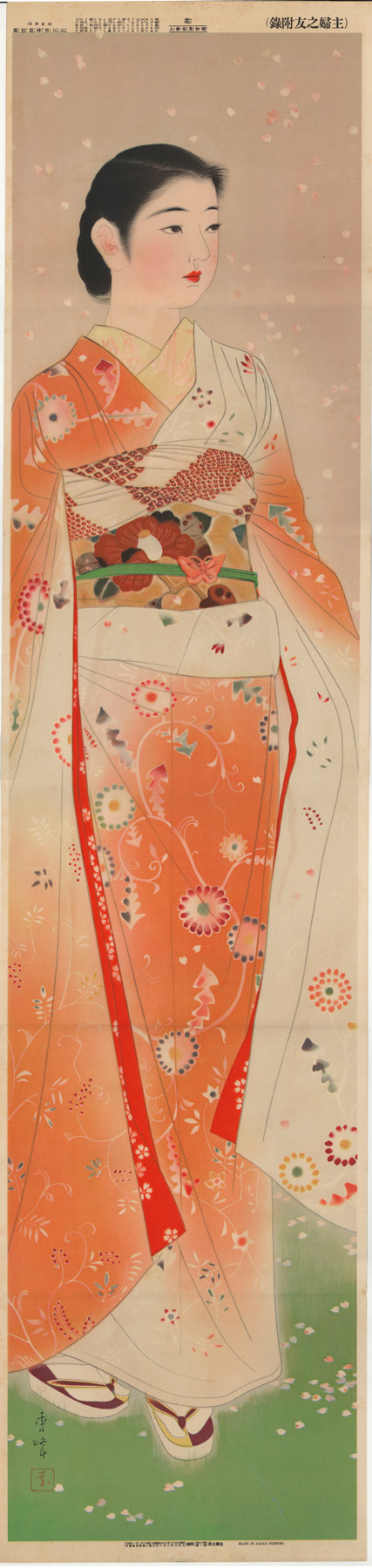

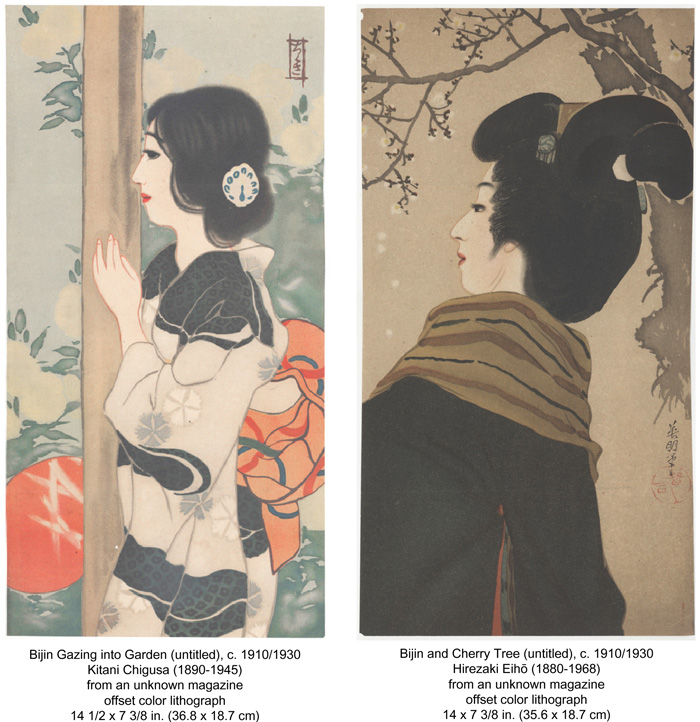

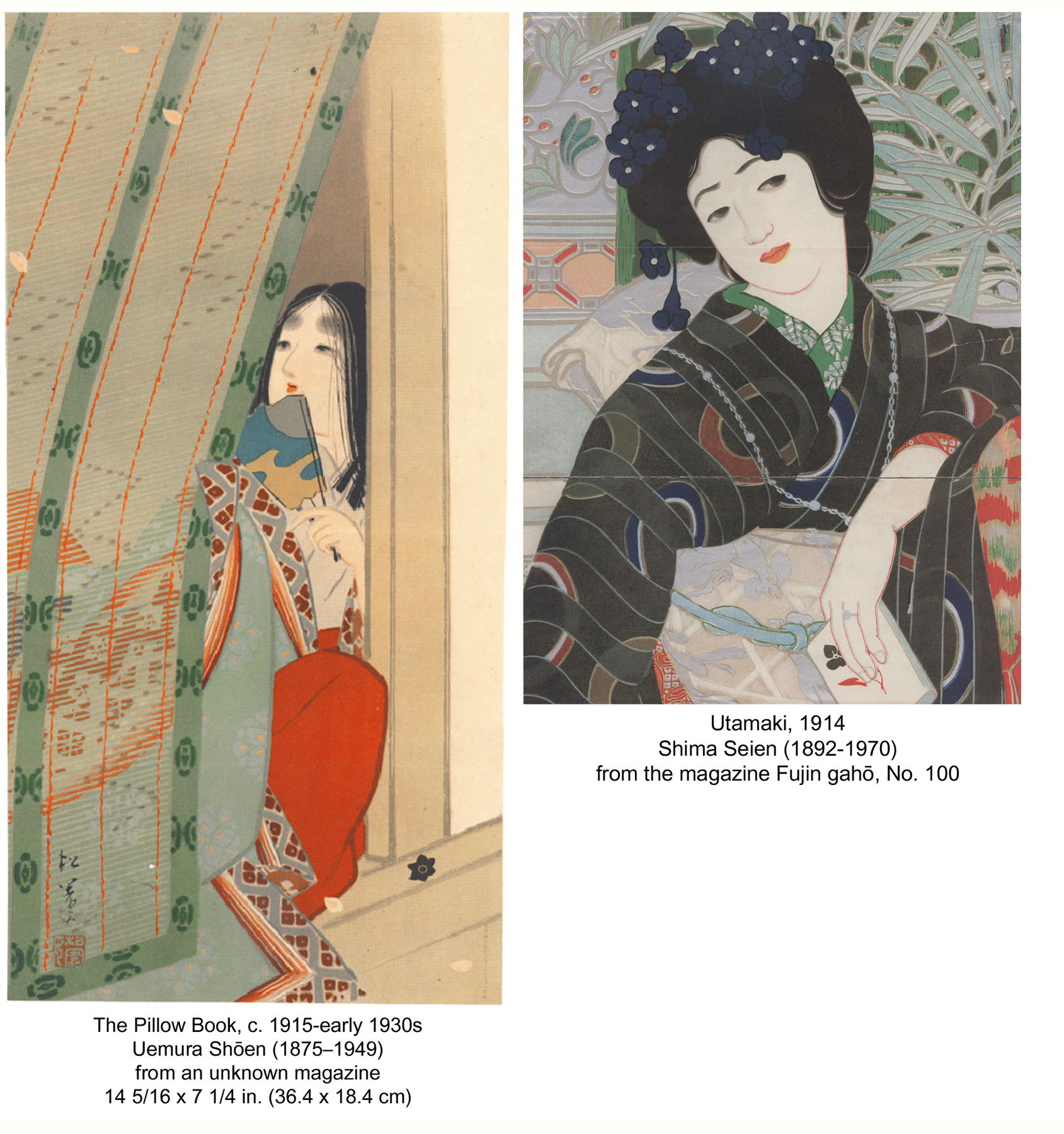

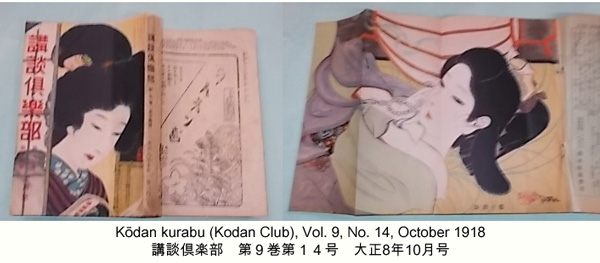

The period 1914 through 1921 has been called by Kendall Brown the "'golden age' of bijin kuchi'e”.1 During this golden age (and continuing into the 1930s), thousands of inserted pictures (kuchi-e), mostly printed using metal plate lithography and photo-offset printing, were commissioned from both well-known and little-known artists by publishers of mass-market popular culture magazines (taishū zasshi). The vast majority of these illustrations depicted beautiful women (bijin) and they appeared as inserted frontispieces, illustrations to serialized novels, advertisements, promotional supplements, as well as cover illustrations.

While employing new technology, the use of inserted pictures in both magazines and novels during this golden age was a continuation of the use of woodblock-printed multi-color illustrations in magazines and novels of the prior late Meiji period, c. 1890-1912, during which time the use of traditional woodblock printing technology for mass reproduction dramatically declined.2

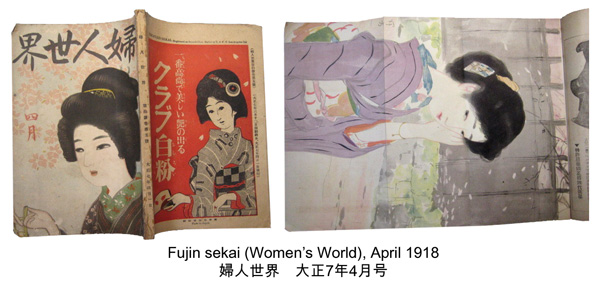

Unfortunately most of the bijin kuchi-e foundfor sale today, as with all but two of this collection’s prints, have become separatedfrom the original magazines they were inserted in, making it impossible todetermine what they may have been illustrating. In collecting these affordableprints, expect to see a characteristic tri-fold as many of the prints werelarger than the dimensions of the magazines they were inserted into.

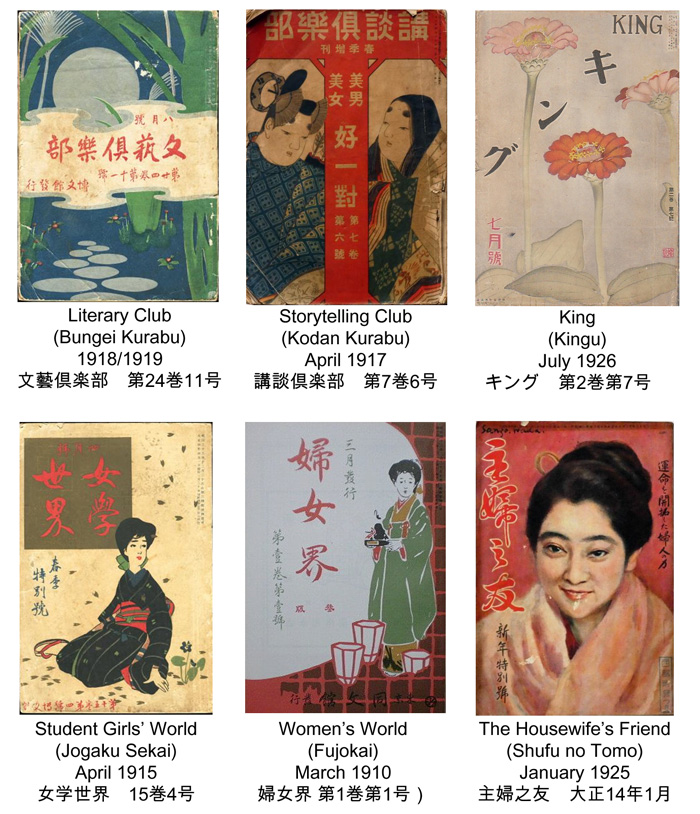

The Magazines Bijin kuchi-e appeared in both general audience magazines, such as Bungei kurabu 文芸俱楽部 (Literary Club, 1895-1933, publisher Hakubunkan), Kōdan kurabu 講談倶楽部 (Storytelling Club, 1911-1962, publisher Dai Nihon Yūbenkai Kōdansha) and Kingu キング (King, 1925-1943, publisher Dai Nihon Yūbenkai Kōdansha), Japan’s first million selling magazine, and magazines specifically targeted at girls and women such as Jogaku Sekai 女学世界 (Student Girls’ World, 1901-1925, publisher Hakubunkan), Fujokai 婦女界 (Woman's Sphere, 1910-1943, 1948-1950, 1952 Dō bunkan; later, Fujokai), Fujin sekai 婦人世界 (Women's World, 1906-1933, publisher Jitsugyō no Nihonsha) and Shufu no tomo 主婦之友 (The Housewife's Friend, 1917-2008, publisher Tokyo kaseikai; later, Shufu no tomosha ), whose monthly circulation was to reach 200,000 in 1927 and grow to over 1,000,000 in the mid-1930s.3 Between 1911 and 1930 over 200 women's magazines and journals began publication, although not all featured bijin kuchi-e.4

The Subject Matter of Women's Magazines

While the Taish ō era (1912-1926) brought with it material benefits and status improvement for many women and saw the emergence of the "new woman" (atarashii onna), mass market magazines targeted for women had an ambivalent attitude about these changes. Source: Yumeji Modern: Designing the Everyday in Twentieth-Century Japan, Nozomi Naoi, University of Washington Press, 2020, p. 102.

The types of articles then featured in women's magazines reveal the inconsistency between traditional roles for women and women's liberation. In 1920, for example, Fujin kōron (Ladies forum) published articles such as "What If Women Were Allowed in Politics?," "The Unavoidable Need for Contraception and Our Nation," and "Bad Wife, Dumb Mother" (a play on the expression ryōsai kenbo, or "good wife, wise mother"). That same year articles in Shufu no tomo (Housewife's companion) included "What Maidens Expect in Marriage," "Words of Advice for Parents: How to Ensure Your Child Enters the Best Middle School or Girls School," and "Reorganizing a Wedding Ceremony and Banquet." While feminist movements were becoming active during the first decades of the twentieth century, the above sampling of articles is indicative of what Frederick [Sarah Frederick in "Girls' Magazines and the Creation of Shōjo Identities"] describes as the contradictory content found in these publications: "They defined women's roles - housewife, school-girl, mother - in newly restrictive ways, but they also generated new possibilities for different identities." |

Of course serialized novels and stories (some written by the magazine's readers) were a constant and, being commercial ventures, women's magazines “touted the newest fashions, household goods, and cosmetics” directing their readers to the department stores where these items could be bought.5 In describing the typical themes for many of the woodblock illustrations appearingin popular women's magazines in the late Meiji period, Julia Meech-Pekarik speaks of the "romantic introspection" of the women depicted, going on to say, "Thestories these prints illustrate typically center on a series of incrediblyfragile and beautiful women from good families who confront personal tragedywith pride and fortitude. Some are driven to avenge the death of a family member,while others commit suicide rather than compromise themselves in love."6 In looking at these Taishō era illustrations we see the persistence of these themes. Source: Dangerous Beauties and Dutiful Wives: Popular Portraits of Women in Japan, 1905-1925, Kendall Brown, Dover Publications, Inc., 2011, p. IX.

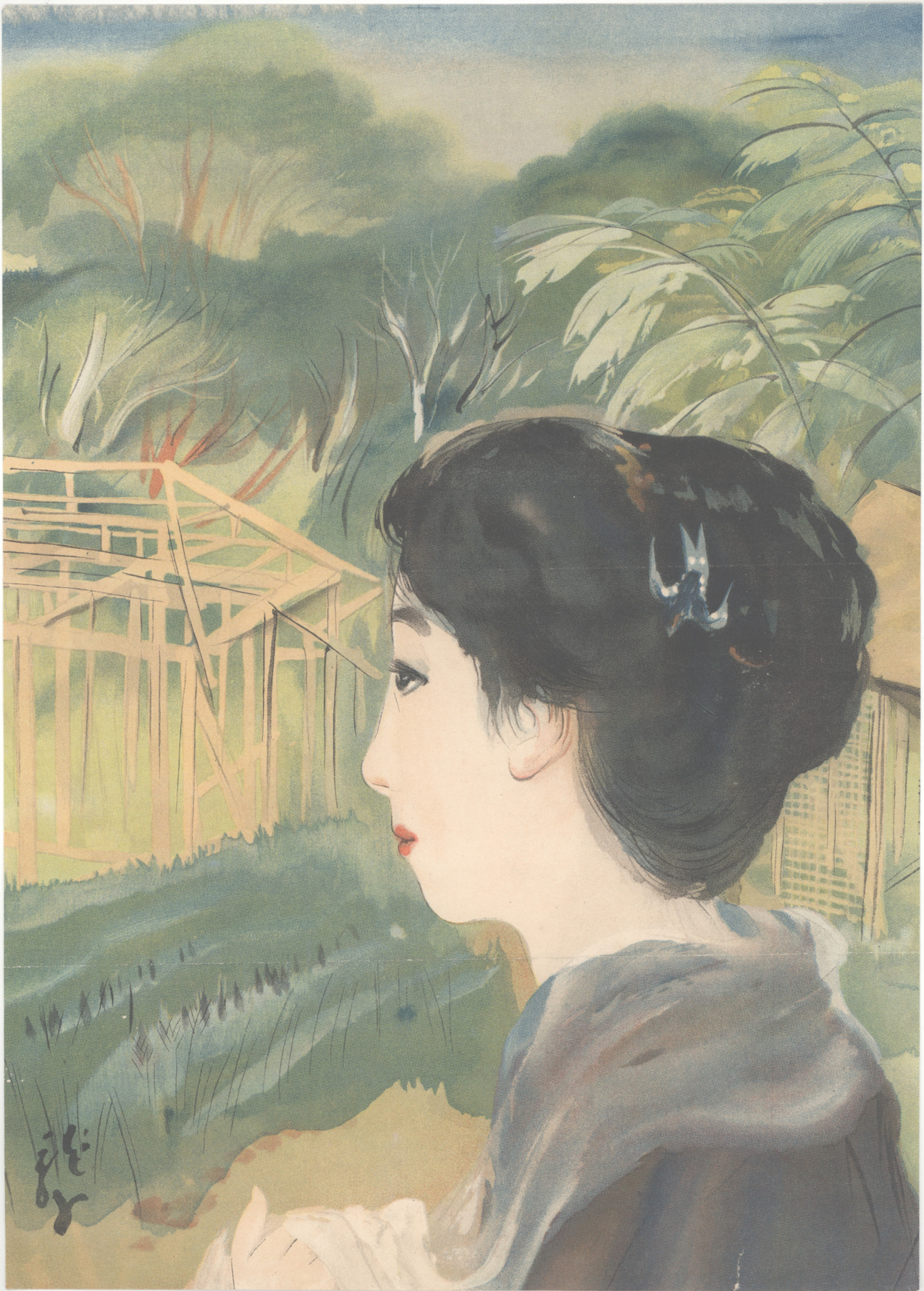

In Taishō kuchi-e, bijin often look out a window to a nearby landscape or to gaze at plants, pose in front of flora, or, in a few cases, pick flowers or tend them. In nearly every image there is a seasonal reference so that the woman stands for the season and for the appreciation of it. Because the clothing of the bijin is linked to the season, the relationship is harmonious. These images invoke an ideology of naturalness by which the particular construct of feminine beauty, and its associations, are naturalized - seen as existing without contrivance. Nature also may function allegorically, so that fresh snow symbolizes purity and cherry blossoms evoke transience. The typical downward cast of the eyes suggests a gaze inward, as is to imply that the lessons of the season are being internalized by the bijin, who is, fundamentally, reflective. This quality of "romantic introspection" to suggest personality and an inner life was carried over from Meiji kuchi-e, where it often expressed melancholy or world weariness. |

Increasing Literacy and Economic Security for Women The great increase inliteracy among women, ushered in by the Ministry of Education’s 1872 compulsoryeducation ruling, specifying that both girls and boys should receive elementaryeducation, along with the growth of private and missionary schools, coupled with improved economic situations for many women in the cities, “allowed an increasingnumber of women to purchase magazines.”7

Teaching Young Girls to Write, c. 1915 Whilethe targeted women’s magazines initially looked to middle and upper class womenfor readership, they also found an audience with working-class women and womenliving in rural areas. And, while the vast majority of readers were women, thesemagazines also attracted curious men.8

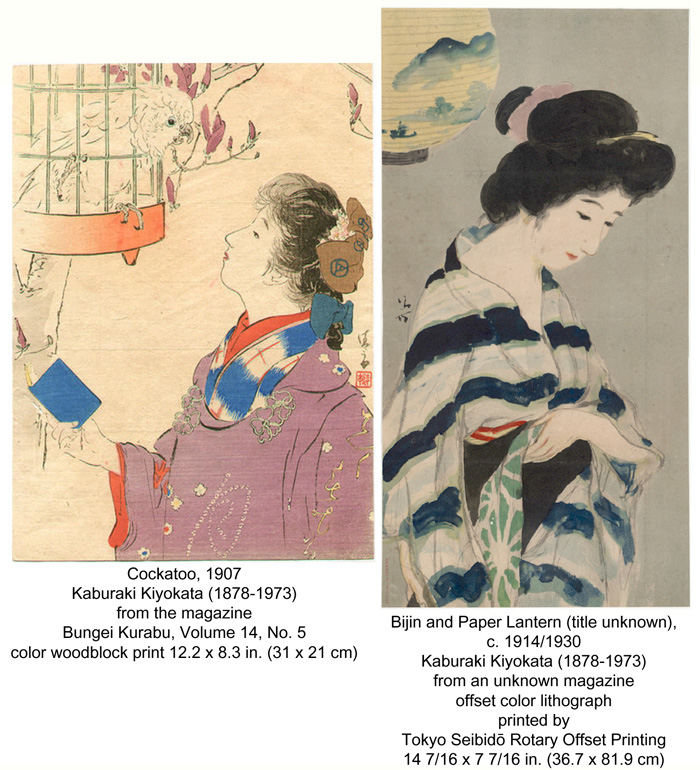

The Artists

From the best-known artists of the day, such as the painter and print designer Kaburaki Kiyokata (1878-1972) and the painter and shin hanga artist Itō Shinsui (1898-1972), to artists working in relative obscurity, the large number of designs required for magazines demanded a large pool of artists to draw from. Both more traditional nihonga (Japanese style) and yōga (Western style) painters found work as illustrators.

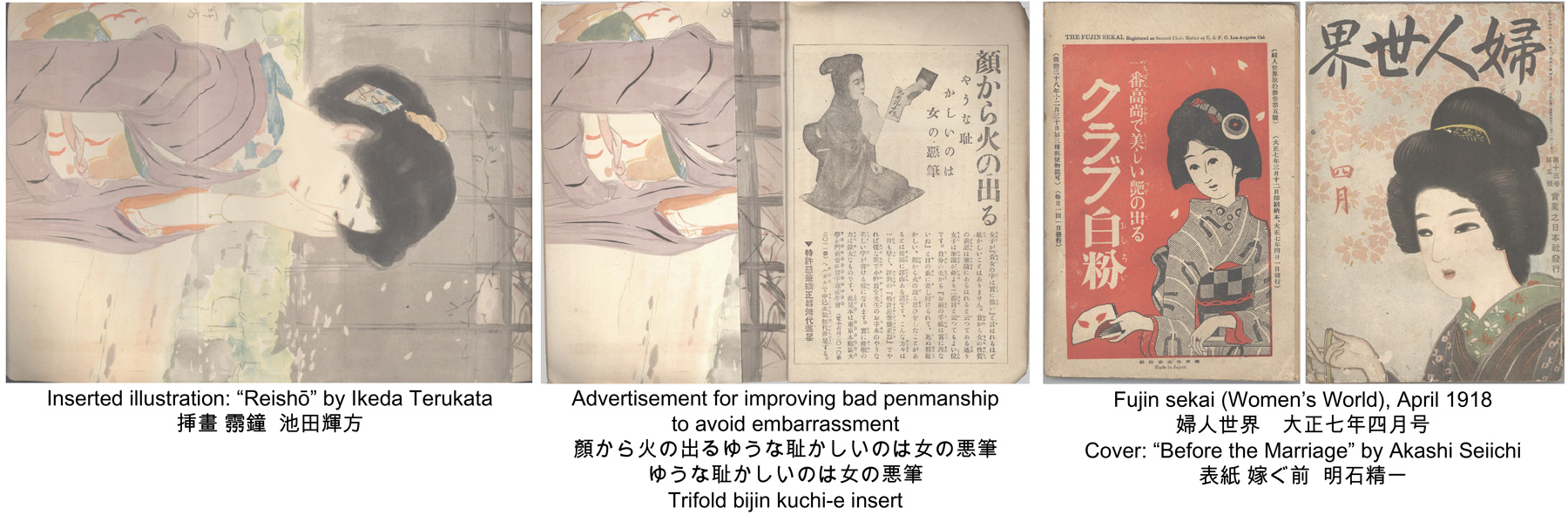

As noted by Kendall Brown, magazine illustrations provided fertile ground for women artists, providing a “critical social space, as well as an economic base.”9 Among the female artists creating bijin kuchi-e, perhaps the two best known are the nihonga style painters Uemura Shōen (1875-1949) and Shima Seien (1892-1970), examples of whose magazine illustrations are shown immediately below. Another women nihonga artist, who as a thirteen year old was sent to study Western style painting in Seattle for two years, and who is represented in this collection, is Kitani Chigusa 木谷千種 (1895-1947), an example of whose work is shown above.10

Artists received relatively low pay for creating an illustration, so they had to work quickly. The artist Hirezaki Eihō 鰭崎英朋 (1880-1968), represented by several prints in this collection, noted that it took him from one to five hours to create an illustration for a magazine. The pay received for designing these illustrations varied according to the artist’s popularity and the magazine commissioning the work. Kendall Brown cites fees being paid during the late Meiji and early Taishō period of three to fifteen yen per illustration, a relatively low amount. 11 Despite the modest fees paid, the number of illustrations required by these very popular magazines could provide significant income for many artists.

The Evolution of Printing Technology and Taishō era Kuchi-e

By the end of the Meiji era (1867-1912), woodblock printing as a means of duplicating text and illustrations for mass distribution was near dead and relegated to the niche markets of making copies of classic ukiyo-e designs and producing deluxe prints targeted at collectors. In a modernized Japan, woodblock printing was considered old-hat by the public, enticed by newer technologies such as lithography and the realism of photography.

Source: Dangerous Beauties and Dutiful Wives: Popular Portraits of Women in Japan, 1905-1925, Kendall Brown, Dover Publications, Inc., 2011, p. XV.

To fully appreciate Taishō kuchi-e, we need not only know their literary content and social context but also understand the technologies used in their production. These technologies were not simply expedient means of mass production, but, in fact, were part of a visual revolution that included the desire to reproduce perfectly the images created by designers, the skilled artistry of master printers, and the creation of luxury prints meant to function as de facto works of art...

The Japanese had used stone lithography since 1874, and copperplate intaglio printing soon afterward. Zinc plate lithographic processes were deployed in the 1880s and 1890s, with photographic collotype printing developed around 1890. By 1902 three-color (red, yellow, blue) chromolithography was deployed, beginning in Bungei Kurabu. Kiyokata adapted it for his kuchi-e in 1905. In that same year, the Marinono rotary magazine printing machine was imported to Japan, allowing for much faster printing. Soon after, the American Rubel rotary press using a rubber sheet was also imported, producing high-quality color printing even on the coarse paper commonly used for mass-circulation magazines. A version of the rotary offset press was manufactured in Japan in 1913, making the technology more affordable. From around 1914 planographic offset lithography using lighter zinc and aluminum plates, rather than heavy, brittle stone plates, made printing easier and cheaper.12 |

During the early Taishō era , the production of these bijin kuchi-e lithographs was similar to the production process for woodblock prints, involving an artist/designer, under contract to a publisher, who created a design, often a painting, that was hand-copied by artisans onto a metal plate, one plate for each color (analogous to the use of multiple carved woodblocks, essentially one for each color, in the traditional woodblock print-making process) and then printed. Later on, the hand-drawing process would be replaced by faster photomechanical processes.

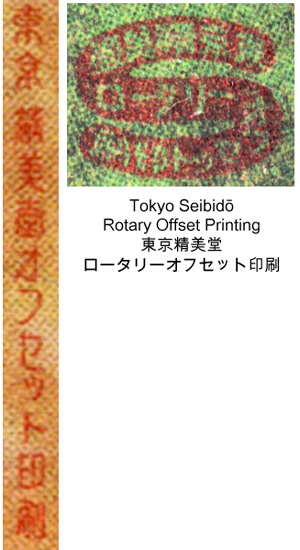

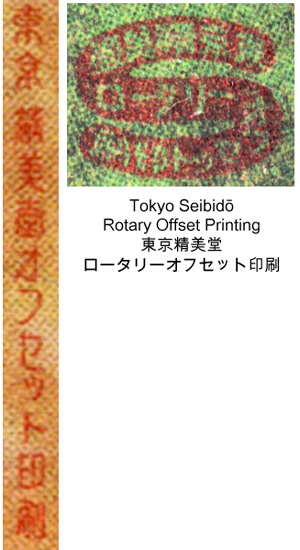

For prints in this collection that show the name of the printing firm, usually printed in extremely small type near the edge of a print and shown as enlargements to the left, the most frequently appearing is that of Tokyo Seibidō Rotary Offset Printing 東京精美堂ロータリーオフセット印刷, possibly associated with the publisher Hakubunkan. For prints in this collection that show the name of the printing firm, usually printed in extremely small type near the edge of a print and shown as enlargements to the left, the most frequently appearing is that of Tokyo Seibidō Rotary Offset Printing 東京精美堂ロータリーオフセット印刷, possibly associated with the publisher Hakubunkan.

The Demise of Bijin Kuchi-e

While the bijin genre, buoyed by the shin hanga movement and its combining of traditional ukiyo-e motifs and traditional woodblock printing methods, coupled with the techniques of modern Western painting, (an alluring combination for foreign collectors), continued well into the 1930s, by the mid-1920s bijin kuchi-e were in decline, as explained by Kendall Brown.

Source: Dangerous Beauties and Dutiful Wives: Popular Portraits of Women in Japan, 1905-1925, Kendall Brown, Dover Publications, Inc., 2011, p. XV.

It is hard to pinpoint any one reason for the decline of the genre, but bijin kuchi-e well may have been the victim of their own earlier success. Once nearly every magazine featured them, bijin kuchi-e became overly familiar and their appearance marked a magazine as old-fashioned and unfashionable.... [B]y the last years of Taishō, ending in December 1926, bijin kuchi-e were considered staid at best, retrograde at worst. |

1 Dangerous Beauties and Dutiful Wives: Popular Portraits of Women in Japan, 1905-1925, Kendall Brown, Dover Publications, Inc., 2011, p. xvii.

2 For more information on woodblock kuchi-e see Woodblock Kuchi-e Prints: Reflections of Meiji Culture, Helen Merritt and Nanako Yamada, University of Hawaii Press, 2000

3 Circulation figures taken from Wikipedia "Shufu no Tomo" https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Shufu_no_Tomo and Women's Magazines and the Democratization of Print and Reading Culture in Interwar Japan, Shiho Maeshima, University of British Columbia, August 2016, p. 4. [A Doctoral Thesis which may be found online at https://open.library.ubc.ca/cIRcle/collections/ubctheses/24/items/1.0314161] 4 “Josei: A Magazine for the ‘New Woman’”, KazumiIshii appearing in Intersections, August2005 (an electronic journal Australian NationalUniversity) http://intersections.anu.edu.au/issue11/ishii.html5The World of the Meiji Print: Impressions of a New Civilization, Julia Meech-Pekarik, Weatherhill, 1986, p. 217.

6Graphic Propaganda: Japan’s Creation of China in the Prewar Period, 1894-1937, a dissertation, Scott E. Mudd, University of Hawai’i, August 200, p. 64. https://scholarspace.manoa.hawaii.edu/handle/10125/11659

7 "Around 1905, perhaps related to the wave of patriotic fervor that swept through Japan at the time of the war with Russia, school attendance figures shot up to nearly universal levels for both boys and girls for the first time." - Source: "Who Can't Read and Write? Illiteracy in Meiji Japan", Richard Rubinger, appearing in Monumenta Nipponica, Summer, 2000, Vol. 55, No. 2 (Summer, 2000), Sophia University, pp. 163- 198; quote on p. 182 Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/2668426

8 See Gender, Consumerism and Women’s Magazines in Interwar Japan, Barbara Sato, Routledge Handbook of Japanese Media, February 2018

9 op. cit. Dangerous Beauties and Dutiful Wives, p. XVI.

10 For a biography of this artist see the website of Kagedo Japanese Art http://kagedo.com/wordpress/g/kitani-chigusa-painting-of-a-beauty-contemplating-her-reflection/

11 op. cit. Dangerous Beauties and Dutiful Wives, p. XVI.12 In 1914 the first offset litho printing in Japan was carried out by Shōsandō (Mizuno Gukichi). It had been invented in the United States in 1906 and then developed in Germany. It allows three-color printing, a clear impression even on poor paper, and economy in the use of printing ink. [Source: Being Modern in Japan, Culture and Society from the 1910s to the 1930s, Ed. Elise K. Tipton and John Clark (Appendix, Chronology, Japanese Printing, Publishing, and Prints, 1860s-1930s, John Clark)

last revision: 3/29/2021 3/19/2021 11/10/2020 10/19/2020 10/13/2020 10/5/2020 created |

For prints in this collection that show the name of the printing firm, usually printed in extremely small type near the edge of a print and shown as enlargements to the left, the most frequently appearing is that of Tokyo Seibidō Rotary Offset Printing 東京精美堂ロータリーオフセット印刷, possibly associated with the publisher Hakubunkan.

For prints in this collection that show the name of the printing firm, usually printed in extremely small type near the edge of a print and shown as enlargements to the left, the most frequently appearing is that of Tokyo Seibidō Rotary Offset Printing 東京精美堂ロータリーオフセット印刷, possibly associated with the publisher Hakubunkan.