Biographical Data

Biography

Iwami Reika 岩見禮花 いわみれいか (1927-2020)Sources: Modern Japanese Prints 1912-1989, Lawrence Smith, British Museum Press, 1994, p. 26; 44 Modern Japanese Print Artists, Gaston Petit, Kodansha International Ltd., 1973, p. 146.

Iwami Reika, pioneer in the post-WWII male-dominated world of Japanese print-making, is the first Japanese woman print artist “to achieve the same status and worldwide recognition as male artists.”1 While born in Tokyo, her early years were spent on the Islandof Kyūshu.2 Returning to Tokyo, but unable to afford regular art classes, she attended Sunday art courses, including printmaking, at Tokyo’s Bunka Gakuin College, graduating in 1955. Before coming to printmaking she tried oil painting and studied doll-making under the “National Treasure” Hori Ryūjo 堀柳女 (1897–1984). While having an early interest in prints, it was not until after seeing the work of the sosaku hanga (creative print) artist Onchi Kōshirō (1891-1955) in 1953-1954 that she took up the study of printmaking, studying with Onchi’s associates Sekinō Jun’ichiro (1914-1988) and Shinagawa Takumi (1908-2009).3 By the mid-1950s, Iwami had “discovered a natural affinity for the paper, wood, and watercolor, and felt that she had found her artistic niche in the execution of woodblock prints.”4 |

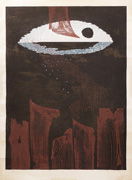

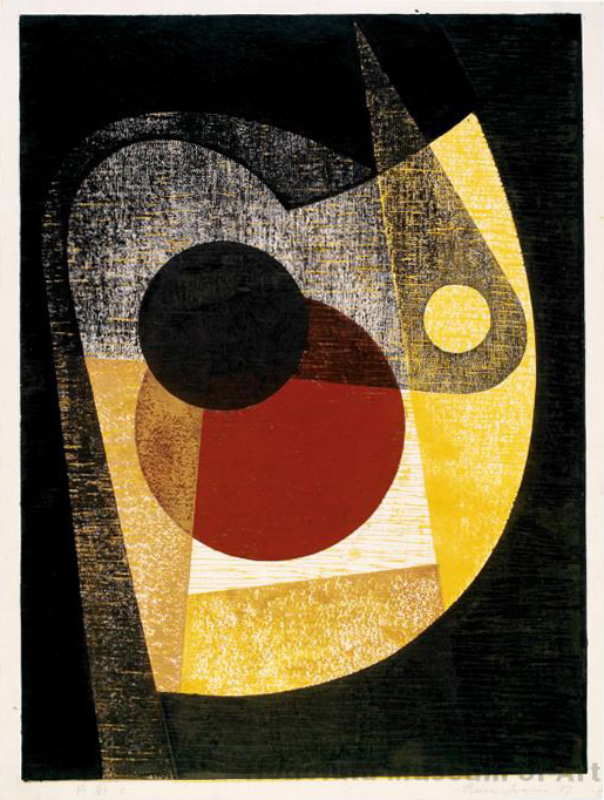

| Circular Shadow No. 5 (Maru-ei No. 5), 1957 Sheet: 23.1 x 23.2 in. scanned from Collecting Modern Japanese Prints, Then and Now, Mary and Norman Tolman | Round Shadow C (円影), 1957 Sheet: (not provided) |

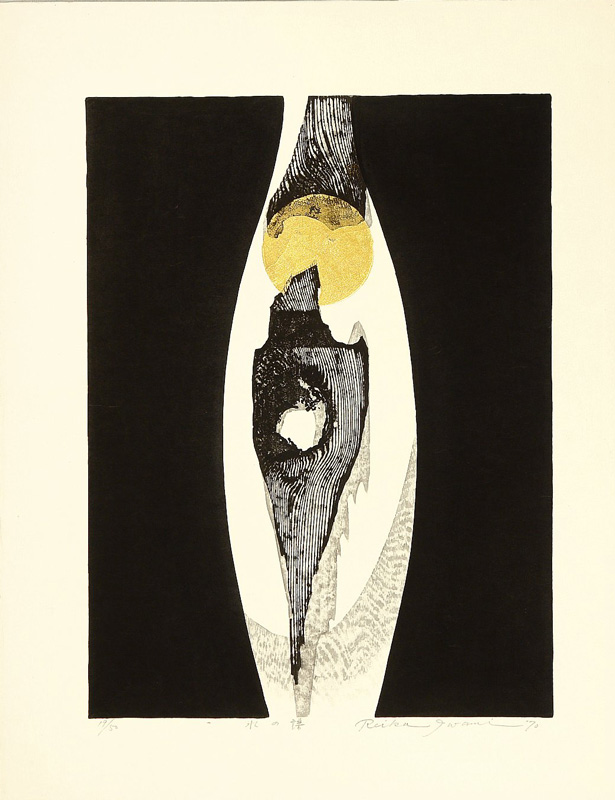

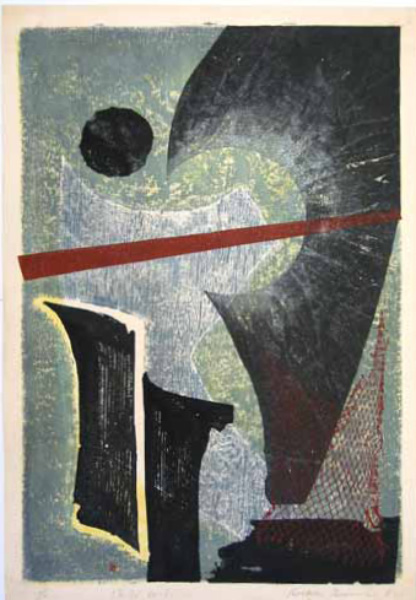

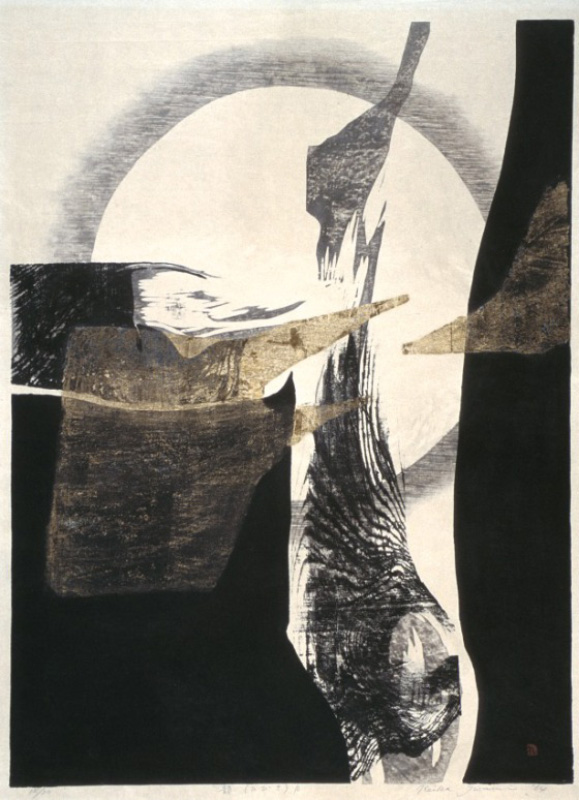

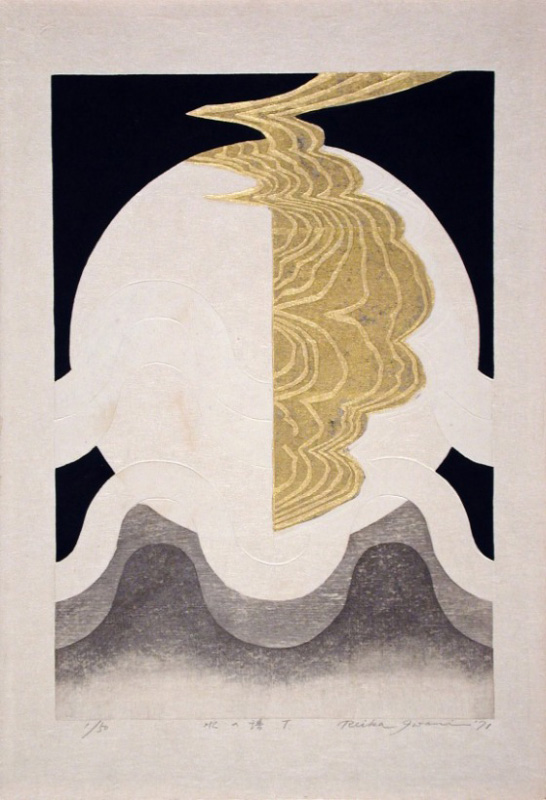

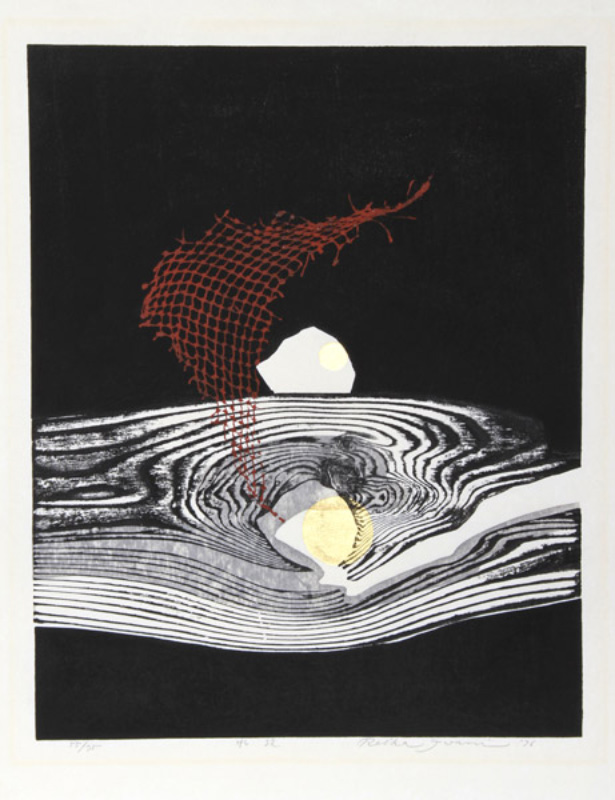

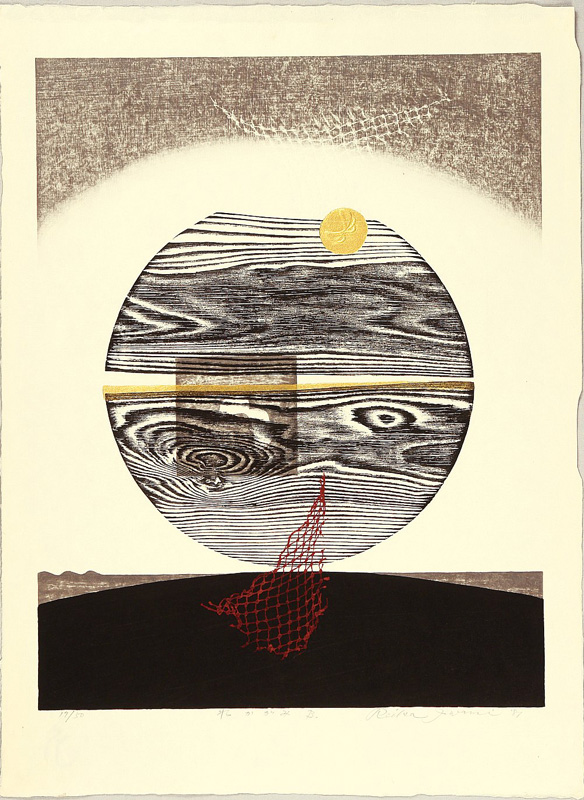

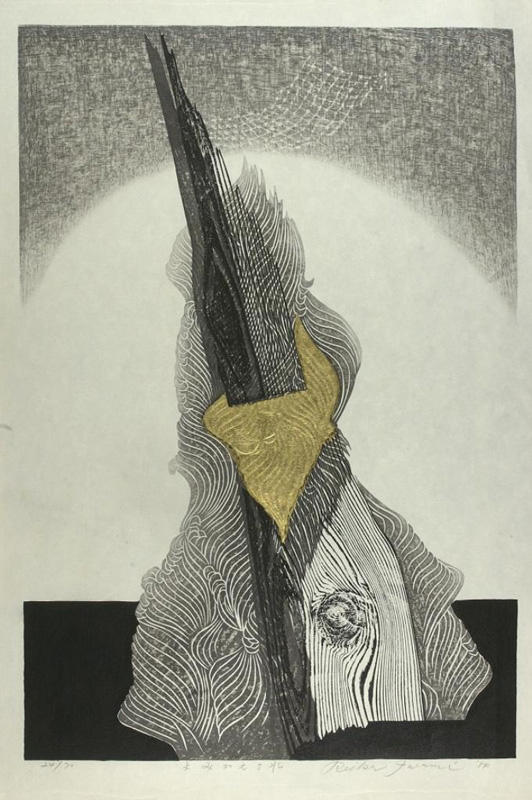

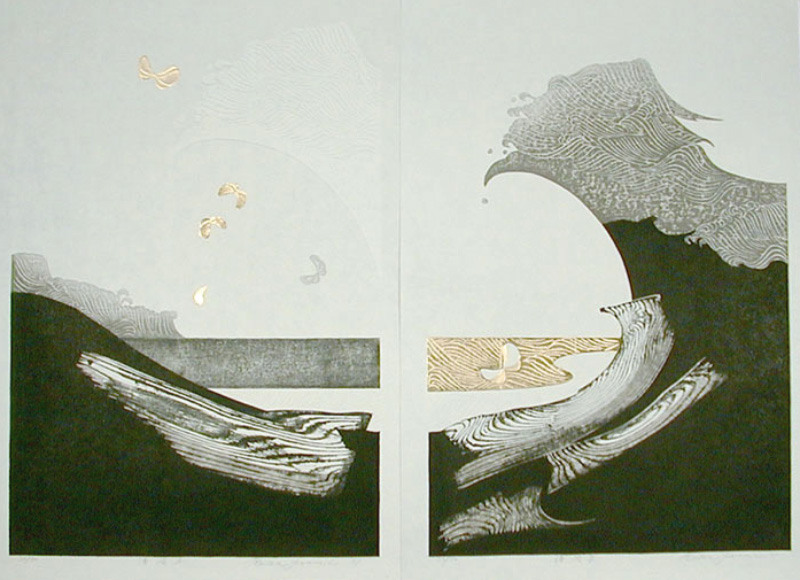

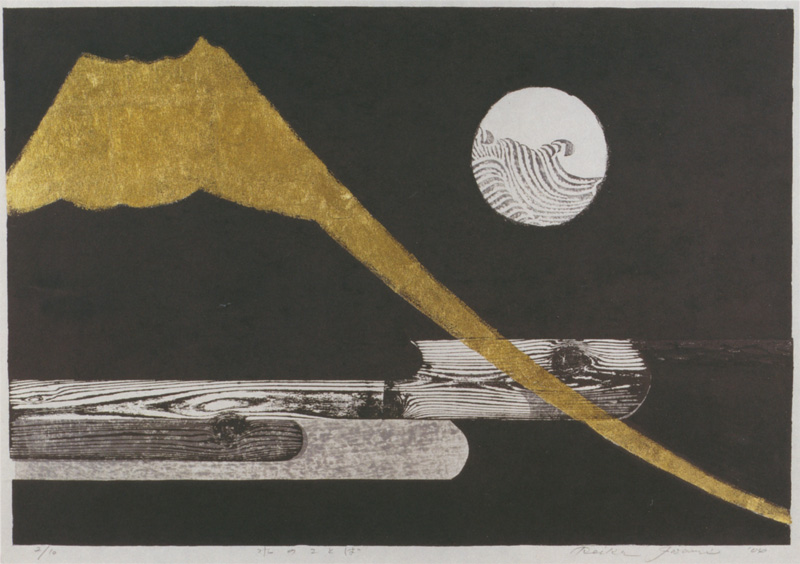

Iwami's earlier works, as can be seen by the two 1957 prints shown above, were geometrical abstractions, employing some color, but starting in about 1970 her work became less abstract, adopting a distinctive vocabulary representing the natural world, particularly of water. Her pallet also moved to primarily black, white and shades of gray enhanced with application of gold and silver foils and the physically demanding technique of embossing. All of these elements remain in her current work.

Iwami's work of the past 40 years is illustrative of J. Thomas Rimer's comments on sosaku hanga that even in their abstraction, creative prints still maintained a sense of "muted realism” and“a sense of craft rooted in instinctive apprehension of the power, the wholeness, of nature itself.”6 Speaking directly of Iwami's work, Rimer praises it for its "sense of craft and elegance" going on to say: "She seldom relies on bright colors, allowing rather the textures and shapes to speak in a wholly natural fashion. She sometimes uses actual objects from nature, such as driftwood7, pressing them to paper to create the subtle textures that make her works distinctive."8

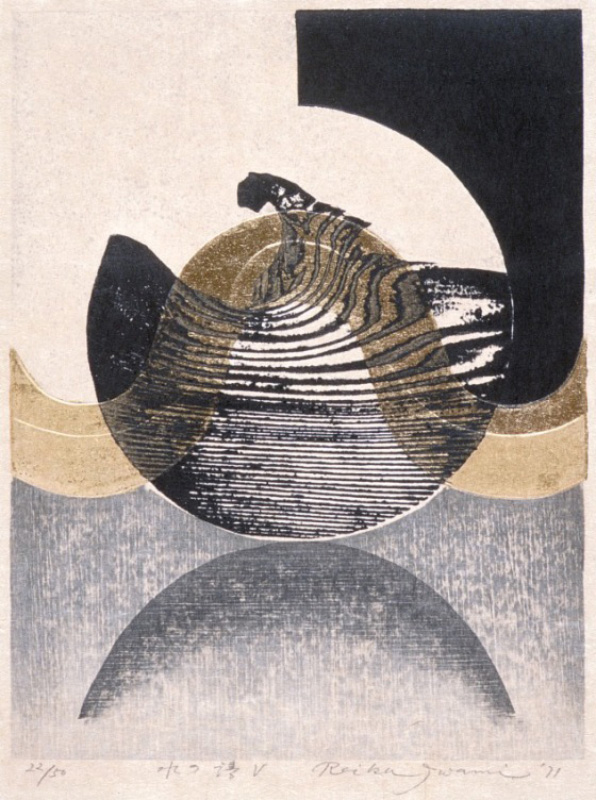

| Musical Note of Water, 1970 Sheet: 23/4 x 18 1/2 in. Artelino website | Water Music V, 1971 Sheet: 13 13/16 x 10 1/16 in. Los Angeles County Museum of Art (AC1995.141.8) |

The consistency of Iwami's work since the early 1970s, in style and theme, are attested to by comments written twenty years apart by the artist and critic Francis Blakemore and Iwami's publisher and dealer for many years Norman Tolman.

From Blakemore, writing in 1975 in Who's Who in Modern Japanese Prints, we see:

Iwami is a rarity among woman woodblock artists in her avoidance of color. Solid, pure blacks are blended with finely textured grays and some metallic gold. Large full moons often dominate the prints, with rocket like golden thrusts piercing them in bold curves. Wavelike patterns like communication symbols sometimes bisect the circles. Sprinklings of powdered mica over the white areas give the impression of windblown sand. In the absence of brilliant colors, form and texture are strongly evident. Technically as well as artistically, Iwami is a polished professional. Driven by a powerful desire for expression, she undertakes each step of the printing process herself – from the cutting of the blocks to the inking and the rubbing of the paper. Especially difficult is the embossing, which requires great physical strength.

Iwami’s devotion to her work is apparent to all who see it. The finished prints have a wholeness that cannot be matched by ordinary production techniques.10

And approximately twenty years later in 1994, Tolman, in Collecting Modern Japanese Prints, Then and Now, states:

Iwami’s world is the world of “natural” Japan. Sumi ink, handmade paper, and real wood are blended to produce her austere yet powerful compositions. Embossing and overlaying silver or gold onto a velvety black background result in a finished work that is elegant in form and design, with a simplicity that is very satisfying to the beholder. Iwami’s subject is water and its flow, and her genius lies in the almost mystical ability to transmute the grain and texture of pieces of wood she has found into visual images of patterns of water. Contrary to popular opinion, she does not use driftwood in her work, simply old pieces of wood that she likes for their distinctive patterns resembling flowing steams or eddies. Sometimes she adds a touch of glittering mica (a stratagem of the ukiyo-e artists) to convey the feeling of water-washed sand in the sun.9

James Michener's Comments on the Artist

And approximately twenty years later in 1994, Tolman, in Collecting Modern Japanese Prints, Then and Now, states:

| Iwami’s world is the world of “natural” Japan. Sumi ink, handmade paper, and real wood are blended to produce her austere yet powerful compositions. Embossing and overlaying silver or gold onto a velvety black background result in a finished work that is elegant in form and design, with a simplicity that is very satisfying to the beholder. Iwami’s subject is water and its flow, and her genius lies in the almost mystical ability to transmute the grain and texture of pieces of wood she has found into visual images of patterns of water. Contrary to popular opinion, she does not use driftwood in her work, simply old pieces of wood that she likes for their distinctive patterns resembling flowing steams or eddies. Sometimes she adds a touch of glittering mica (a stratagem of the ukiyo-e artists) to convey the feeling of water-washed sand in the sun.9 |

James Michener's Comments on the Artist

Writing before she adopted her characteristic style discussed above, Michener in his seminal 1962 book and portfolio of original prints, The Modern Japanese Print - An Appreciation, (see a discussion of Michener's book and portfolio below) discussed his introduction to the artist and her work:

I can recall the day on which I was passing an art store in Tokyo and saw a copy of the first print that Miss Iwami was offering to the public. At the time I supposed thea rtist was another of the gifted young men who were knocking for admission to the ateliers of critical review, and I remember thinking: “That one might make it.” But as I was about to pass by, I stopped to restudy the beautiful use of texture which characterized this unknown print, its vivid yet controlled coloring, and its wholly satisfying composition. I concluded then that this Iwami, whoever he was, had already reached a point rather more advanced than competing artists who were just then appearing on the scene, and I went inside to make inquiries. The man in charge did not then know that Iwami-san was awoman, but he did have two other samples of the artist’s work, and I bought all three. . . . The more I kept the three prints before me, the more I grew to like them. The attributes that I had liked originally increased in merit: texture, control of design, color, emotional satisfaction. I convinced myself that Mr. Iwami was destined to be an artist. I therefore set out to find what I could about his life and his working habits. To my surprise I found that . . . Iwami-san was a young woman who had arrived on the Tokyo art scene by the way of doll-making, with a roll of prints, and everyone who had seen them had been impressed. They were not yet perfect prints, and some critics thought she would never attain perfection, but she won encouragement and a few sales. At big shows I began to spot her work, and it maintained its high standards. Her coloring improved, if anything, and her sense of spacious design continued to provide her with subject matter that caught the mind’s eye. She was on her way, and I felt an inward glow of satisfaction. One day, on a crowded street off the Ginza, I was stopped by an earnest young woman of no particular appearance. I can’t recall now whether she wore glasses or not. It was midwinter and she was well bundled up in the Japanese manner. I seem to retain the impression of a girl somewhat taller than average and not at all bad looking. She knew almost no English and I no Japanese, but she said “Aren’t you Mr. Michener?” and I replied that I was. She said that she appreciated the interest I had taken in her work, and I told her that I was convinced she would one day be a most commendable artist. We bowed, then bowed again and started to go, but I took her by the hand in the American manner and shook it warmly, saying: “I’m sure you’re going to be very good, Iwami-san. Keep working.” She could not have understood what I was saying, but it was obvious that she knew. How pleased I was, some years later, to discover that the judges of the competition had nominated not one of her lovely prints, but two. |

A Chronological Sampling of the Artist's Work

unread work of 1960

Image: 34 x 22 3/4 in.

Poem, B 1964

Sheet: 29 1/8 x 21 5/16 in.

Los Angeles County Museum of Art

(M.86.147.40)Concert of One, C

(Hitori dake no ongakkai

一人だけの音楽会 C) 1967

Sheet: 27 1/4 x 20 1/4

British Museum 1986,0321,0.271

Zero in Water H, 1970

Sheet: 34 5/16 x 23 3/16 in.

Los Angeles County Museum of Art (AC1995.141.9)

Sheet: 20 x 13 7/8 in

Los Angeles County Museum of Art (M.2000.110.3)

Water Ripples, 1976

Sheet: 26 x 20 in.

Mirror of Water - B, 1981

Sheet: 20 1/4 x 27 3/4 in.

Artelino Gallery

Rebirth of Water

(Yomigaeru mizu),1984

Sheet: 30 1/2 x 20 7/8 in.

National Museums of Scotland

Uranami A & B, 1987 (diptych)

Sheet: 31 x 21 in. each

Castle Fine Arts

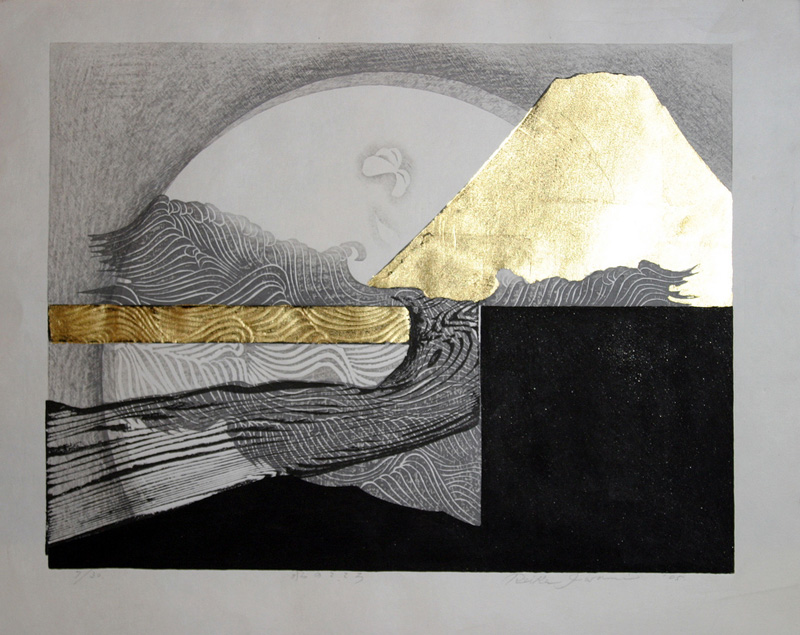

Focus of Water, 2004

Size: 21 3/4 x 30 3/4 in.

scanned from the catalog of the 49th CWAJ Print Show

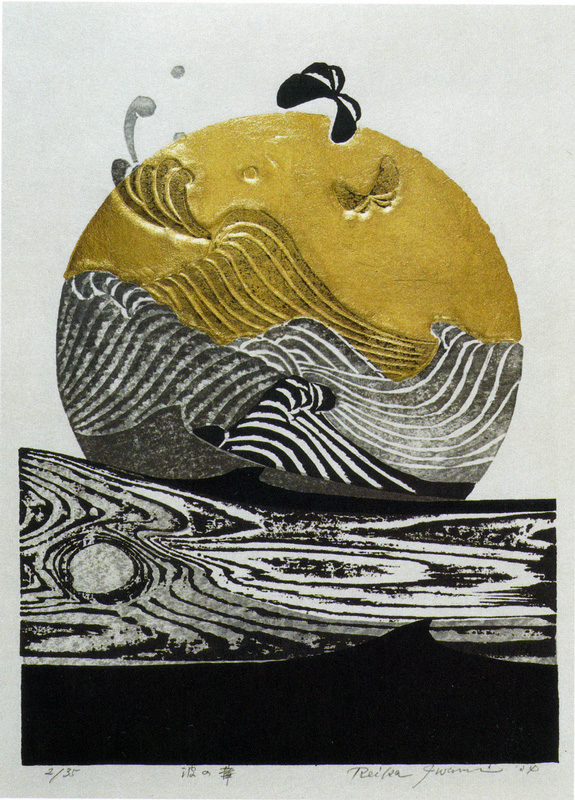

Flowery Wave, 2004

Size: 12 1/2 x 9 1/2 in.

Spirit of the Water, 2005

Size: 17 x 23 1/4 in.

Collections (a partial list)

Art Gallery of New South Wales; Art Institute of Chicago; British Museum; Carnegie Museum of Art; Griffith University Art Collection, Australia; Harvard Art Museums/Arthur M. Sackler Museum; Indianapolis Museum of Art; Jordan Schnitzer Museum of Art, University of Oregon; Los Angeles County Museum of Modern Art; Library of Congress; Museum of Fine Arts, Boston; National Museum of Modern Art, Osaka; National Museums of Scotland; Nickle Arts Museum, University of Calgary; Mead Art Museum at Amherst College; Portland Art Museum; Queensland Art Gallery, Australia; The Smithsonian’s Museums of Asian Art Freer|Sackler; Spencer Museum of Art, University of Kansas; Weatherspoon Art Museum, University of North Carolina; Yale University Art Gallery.

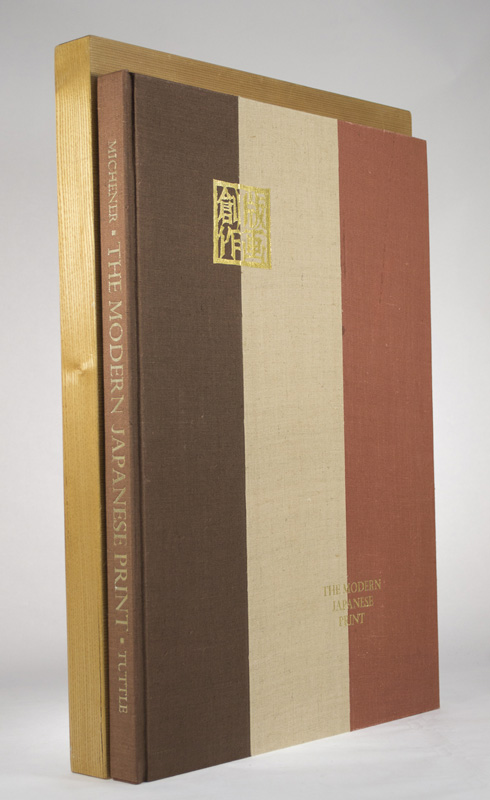

The Modern Japanese Print - An Appreciation by James Michener

James Michener was an avid Japanese print collector and scholar, collecting both the prints of the great ukiyo-e masters, such as Utamaro, Sharaku, Hokusai and Hiroshige, and modern “creative print” (sosaku hanga) artists, such as Onchi Koshiro, Shinagawa Takumi, Kitaoka Fumio and Yoshida Toshi. (See A Very Brief Introduction to Ukiyo-e, Shin Hanga and Sōsaku Hanga.) In 1959, in an effort to publicize and promote the work of sosaku hanga artists, many of whom Michener knew personally, he proposed issuance of a limited edition portfolio, in book form, of original contemporary prints with commentary. The book, titled The Modern Japanese Print – An Appreciation, was issued in 1962 and “met with wide critical and commercial acclaim.” It was instrumental in promoting the careers of the ten artists whose work was included: Hiratsuka Un'ichi (1895-1997), Maekawa Senpan (1888-1960), Mori Yoshitoshi (1898-1982), Watanabe Sadao (1913-1996), Kinoshita Tomio (1923-c.2011), Shima Tamami (1937-1999), Azechi Umetarō (1902-1999), Iwami Reika (b. 1927), Yoshida Masaji (1917–1971) and Maki Haku (1924-2000) and in bringing to the world’s attention the artists and the work of the post-WWII sosaku hanga movement. Prints to be included in the folio were chosen by a panel of art experts |

I was so sad to hear from her niece that IWAMI Reika died on March 18th, 2020. Diminutive in stature, she was capable of making powerful woodblocks which spoke of her love of nature. Reika-san lived most of her life by the seacoast at Hayama, and would frequently walk on the beach, collecting odd bits of driftwood and cast-off fishing nets that she inked and used in her work.

James Michener discovered her work in the 1950s and included her in his seminal 1962 book The Modern Japanese Print: An Appreciation, commenting on her beautiful use of texture, the vivid yet controlled coloring, and the wholly satisfying composition of her oeuvre.

When my parents opened their gallery in 1972, she was one of the first artists they represented. I was a young girl then and found it interesting that she had gotten into woodblock print making through Kokeshi doll carving. She also created intricately inlaid tea caddies in which to store green tea powder for traditional tea ceremony.

Our artists are part of our extended family, especially because our actual relatives lived in the US during the time that my sister and I were growing up in Japan. I therefore found it quite normal to be told, during my junior year abroad in Paris, that Reika san would be coming with my family so that we could all celebrate Christmas together. She confessed upon arrival that that it was her first trip to Europe, and I planned an exhaustive itinerary, knowing that as an artist, she would of course want to visit the Louvre first.

Paris in the winter can be cold and damp but we bundled up and sallied forth into the elements. I couldn’t wait to see her expression when she glimpsed the Mona Lisa, although I knew that, tiny as she was, the crowds might be overwhelming. Indeed, there were throngs in the gallery where the Mona Lisa is located and as I energetically pushed my way through the horde, I realized at one point that I had lost her. Frantically re-tracing my steps, I searched gallery after gallery but to no avail. After a few miserable hours I returned crestfallen to the apartment and announced to my family: “I lost Reika-san”. As we were discussing what we should do to locate her, and whether or not we should call the police or return all together to the Louvre and scour the adjacent streets for her, Reika-san returned, cheeks flushed, chattering away about her “wonderful stroll through the museum after she realized that we had been separated, and the walk home through the picturesque streets of Paris”.

That incident taught me early on that being petite does not mean one is helpless and made me appreciate the strength emanating from her woodblocks all the more.

1 Collecting Modern Japanese Prints, Then and Now, Mary and Norman Tolman, Charles E. Tuttle Company, 1994, p. 204.

4 44 Modern Japanese Print Artists, Gaston Petit, Kodansha International Ltd., 1973, p. 146.

5 Other founding members include Shishido Tokuko (b. 1930), Minami Keiko 1911-2004, Kobayashi Donge (dates unknown)

6 Cinematic Landscapes: Observations on the Visual Arts and Cinema of China and Japan, Linda C. Ehrlich, University of Texas Press, 1994, p. 268.

7 Regarding Iwami's use of actual driftwood to create patterns in her work, Tolman disputes this, as can be seen in his comments further along in this bio. Either way, not a big deal, as whatever mechanism or object she uses to achieve the feeling of water and its flow, it is effective.

8 Collected Writings of J. Thomas Rimer, J. Thomas Rimer, Japan Library, 2005, p. 66.

9 op. cit., Collecting Modern Japanese Prints, Tolman.

10 Who's Who in Modern Japanese Prints, Frances Blakemore, Weatherhill, 1975, p. 54.

11 Historically, the world of Japanese prints had been almost exclusively male and even in the post-WWII era, there were few opportunities for women print artists. Fortunately, with the efforts of individual women artists and the importance of the College Women’s Japan Association's annual show in introducing new artists, more women print artists have gained prominence.