About This Print

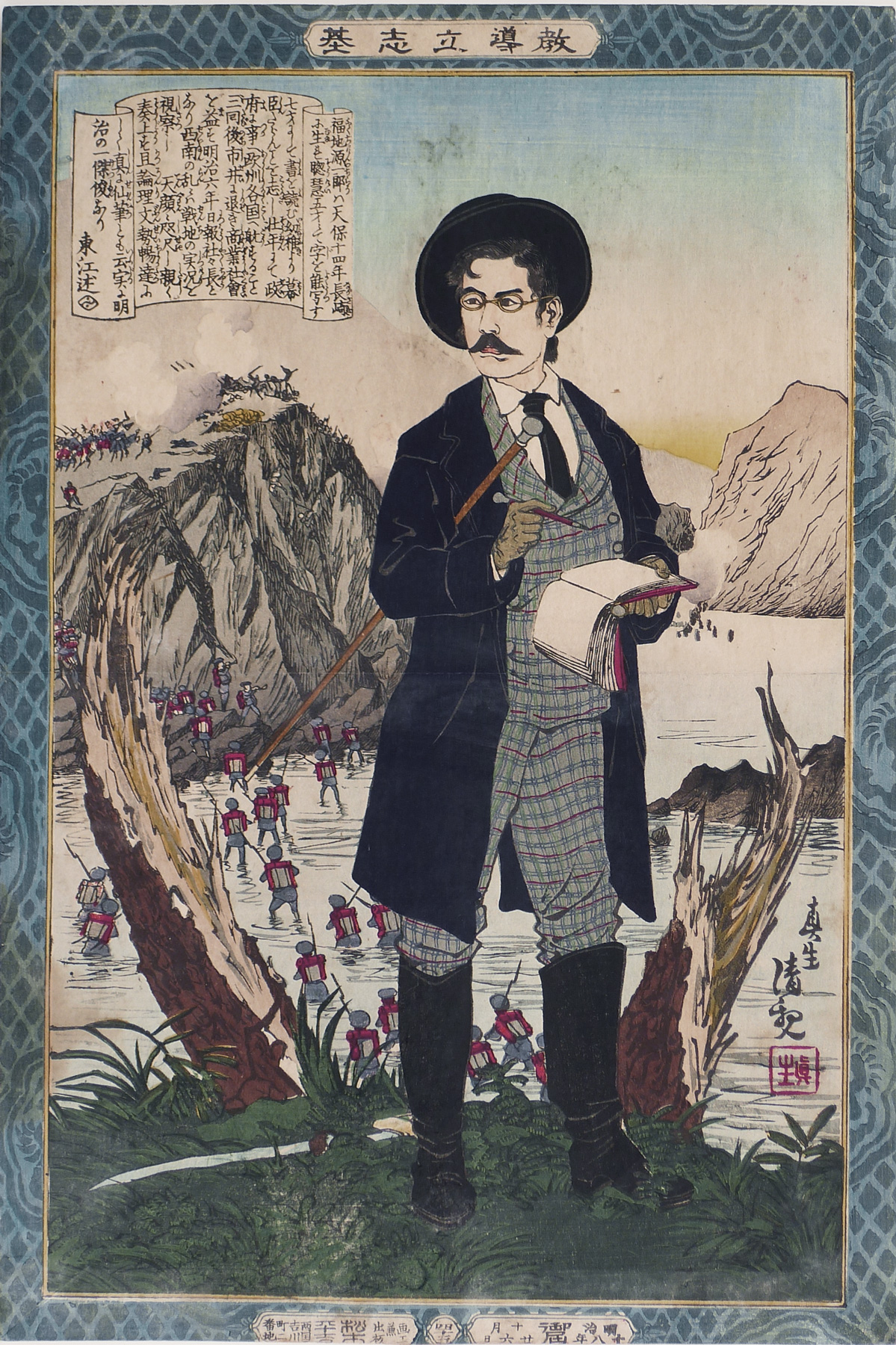

Print number 四五 (45)1 in the series Instructive Models of Lofty Ambition picturing the journalist FukuchiGen’ichirō 福地源一郎 (1841-1906) standing on a hill top while reporting on the government assault on rebel troops during the 1877 Satsuma Rebellion. This print is the most famous in the series and is one of the two prints in the series to portray a contemporary figure.Kiyochika contributed 20 prints to this series. As Smith states: "Thestyle of Kiyochika’s offerings to Instructive Models of LoftyAmbition was decorous and even stiff, as befitted the didacticemphasis of the whole [series.]"2

Source: Kiyochika Artist of Meiji Japan, Henry D. Smith II, Santa Barbara Museum of Art, 1988, p. 74-75.

The portrait of Fukuchi Gen’ichirō was much closer to home for Kiyochika, showing a man who was just six years older than the artist and still very much alive when the print appeared in 1885. The text is by the publisher, Matsuki Tōkō; possibly there was some personal connection among Fukuchi, Matsuki, and Kiyochika, all of whom were former shogunal retainers. (The only other living person portrayed by Kiyochika in this series was Tokugawa Keiki, the last shogun.) The text reads:

Kiyochika’s portrait shows Fukuchi in dapper attire, cane under arm, taking notes on the military action in Kyushu; in the distance, we can make out government troops with red packs fording a river and mounting a hill where a fierce battle is under way, with Satsuma rebels tumbling off the cliff. The jagged tree stumps to either side suggest the devastation of the war, while the discarded sword might symbolize the final destruction of the samurai class, a fate to which this particular samurai, like Kiyochika himself, has responded by taking up the brush.

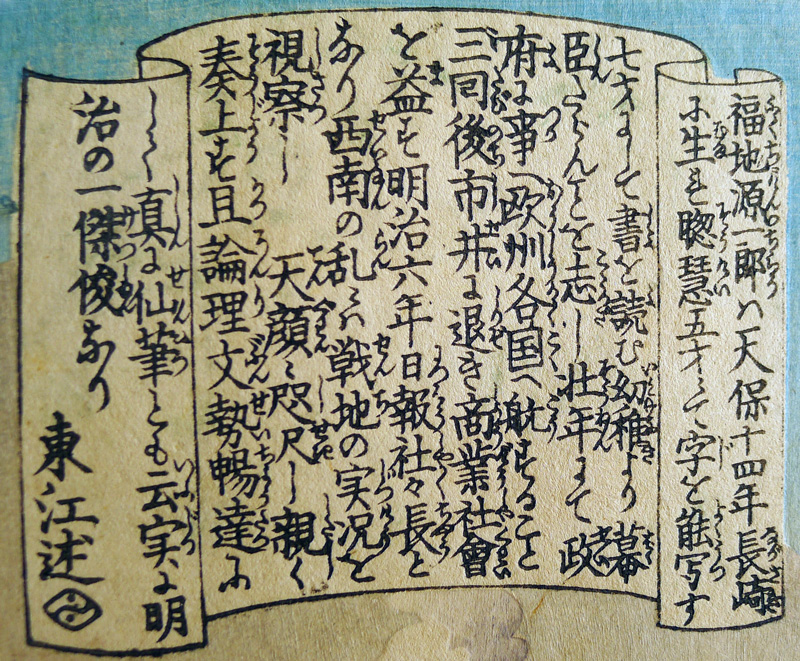

Fukuchi Gen’ichirō was born in Nagasaki in 1843 [an error for 1841]3. He was very bright, and could copy characters at the age of five and read at the age of seven. He aspired from childhood to be a retainer of the shogun, and came to serve the government as a young man, traveling three times to European countries. He then withdrew from public service and launched commercial enterprises. In 1873, he became president of the Nippōsha, and at the time of the Satsuma Rebellion, he observed conditions at the front and reported them in detail before the emperor. His literary and logical skills are polished; he is a virtual wizard of the brush. He is truly one of the heroic figures of Meiji.

The Japanese could muster self-reliant modern heroes of their own. In 1885 Kobayashi Kiyochika (1847-1915) included the newspaperman Fukuchi Gen-ichirō (1841-1909) in the series entitled Self-made Men Worthy of Emulation (Kyodo risshiki). Kiyochika was one of several artists who contributed to this series, and when it was completed in 1890 the publisher was singled out for special recognition by the government for having sponsored such noble subject matter. A didactic text incorporated into the print gives inspirational biographical details (and an incorrect birth date):

Fukuchi Gen’ichirō was born in Nagasaki in 1844. An exceptionally bright child, he could recognize characters at age five and had begun to read and write at about age seven. He resolved to enter the service of the shogunate and, upon coming of age, entered the government, in the service of which he traveled three times to Europe. He then entered into a successful business career.

In 1874 he became president of Nippōsha. He personally covered the Satsuma Rebellion in the south. Received by the emperor, he respectfully recounted his observations to the throne. His style seemed almost supernatural in its logic, force and lucidity. He is one of the truly great men of Meiji.

opportunity resulted from the magnificent benevolence of our imperial sovereign, a man who grieved so deeply over the troops’ casualties and the people’s war sacrifices that he deigned to listen to the report of a man who knew the war situation intimately. And he did this even though I was but a journalist, a common man!

Fujuchi’s paper, like most of the early Meiji press, had an establishment bias, and was respectful of authority and nationalist sentiment. It was guided by the idea of the “good of the nation,” but the phrase referred more to the state at the top than to the citizen at the bottom. Fukuchi’s editorials carried tremendous weight and he provided a suitable model of conduct for Japanese youth – almost too good to be true. In fact, by the end of the 1880s he was heavily in debt and approaching bankruptcy; in 1888 he was discharged from the Nichi niche shimbun, ostensibly due to a nervous disorder. It was “a whimpering end to a dynamite career” as a newspaperman, although he subsequently plunged into the field of literature, helping to construct the Kabukiza – the largest theater in the country – and becoming the theater’s chief playwright, as well as a prodigious novelist.

1 Numbering of the prints was haphazard during the production of the series. Print numbers were sometimes inadvertently omitted; some prints in the series were never assigned numbers and a few of the same numbers appear on different prints.

2 Kiyochika Artist of Meiji Japan, Henry D. Smith II, Santa Barbara Museum of Art, 1988, p. 74.

3 Actual date in the cartouche is Tenpō 14.

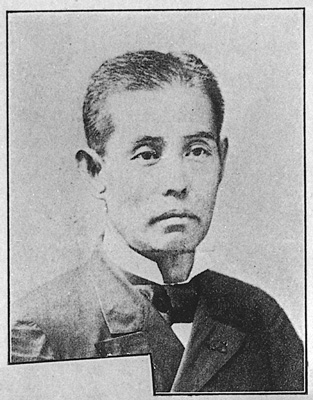

Source: National Diet Library website http://www.ndl.go.jp/portrait/e/datas/319.html?cat=161

| Occupation, Status: Journalist, Literary Figure, Statesman Birthplace(modern name): Nagasaki Date of Birth and Death: May 13, 1841 - Jan. 4, 1906 Pen name etc.: Fukuchi, Ochi Yumenoyashujin Description: Statesman, journalist and literary man. Born in Nagasaki. He undertook Dutch studies and English studies in Nagasaki and Edo. In 1859, he started serving for the Tokugawa shogunate. He traveled twice to Europe as a member of the mission sent by the Shogunate. In 1868, he launched the "Koko Shimbun" newspaper and criticized the new government, for which he was placed under arrest. In 1870, he started serving for Ministry of Finance and attended to both Hirobumi Ito's visit to the United States and Iwakura Mission. From 1874 to 1888, he worked as chief editor and president of the newspaper "Tokyo Nichinichi Shimbun" and had extensive authority in the press world as a government-affiliated newspaper journalist. Later, he was active in various fields, writing political fiction and Kabuki scripts, and joining the movement for modern theater. In 1904, he was elected as a member of the House of Representatives. |

Another Impression/State

Transcription of Scroll

Source: with thanks to Yajifun http://yajifun.tumblr.com/教導立志基 福地源一郎 小林清親 1885年

Transcript: [scroll text by 東江 Tōkō]

This series ran between October 1885 and November 1890 and featured a long list of heroes and heroines, from antiquity to contemporary times, who were regarded as standards of moral leadership and self-realization.

This series of 58 prints,1 plus a table of contents sheet (目録), were originally published between October 1885 and November 1890 by the Tokyo publisher Matsuki Heikichi 松木平吉.2 The table of contents sheet issued by the publisher states that "fifty prints make up the complete set (五十番揃)". Three prints not in the initial release were added over the five year publication period, as were five redesigns of original prints, eventually increasing the total print count to 58. The seven artists contributing prints were Kobayashi Kiyochika (1847-1915) [20 prints], Mizuno Toshikata (1866-1908) [16 prints], Inoue Tankei (Yasuji) (1864-1889) [13 prints], Taiso (Tsukioka) Yoshitoshi (1839-1892) [5 prints], Yōshū Chikanobu (1838-1912) [2 prints], Toyohara Kunichika (1835–1900) [1 print], and Hachisuka (Utagawa) Kuniaki II (1835-1888) [1 print]. All the artists, with the exception of Yōshū Chikanobu, are listed in the top scroll of the table of contents sheet. Various colors (including blue, blue/green, and tan/brown) were used for the decorative border, and in 1902 the series was re-issued by Matsuki without borders.

Brief texts contained within a scroll-like cartouche appearing on each print provide historical details. The scroll composer's name is given at the end of the scroll text. The “lofty ambition” of the title is a Confucian concept, originally from Mencius, meaning “righteous determination that would inspire others.” The market for the series probably included former samurai, ambitious youth, and conservative intellectuals.

"[W]hen it was completed in 1890 the publisher was singled out for special recognition by the government for having sponsored such noble subject matter."3

1 The Tokyo Metropolitan Library online collection shows 50 prints and a Table of Contents sheet. The Table of Contents lists the titles of 50 prints. Smith in Kiyochika Artist of Meiji Japan identified 52 prints. I have identified 58 prints from this series including five prints (Ikina, Michizane Sugiwara, Kesa Gozen, Soga Brothers and Hokiichi Hanawa) that were re-designed and re-printed, likely due to damaged or lost blocks.

2 Robert Schaap notes in Appendix II, p. 166 of Yoshitoshi, Masterpieces from the Ed Freis Collection, Chris Uhlenbeck and Amy Reigle Newland, Hotei Publishing, 2011 that the series originally appeared as newspaper supplements.

3 The World of the Meiji Print: Impressions of a New Civilization, Julia Meech-Pekarik, Weatherhill, 1986, p. 122.

Print Details

| IHL Catalog | #881 |

| Title or Description | Fukuchi Gen'ichirō 福地源一郎 |

| Series | “Instructive Models of Lofty Ambition” (Kyodo risshiki 教導立志基) [note: seriestitle also listed as 'Kyodo Risshi no Moto', ‘Kyodo risshi no motoi’,‘Kyōdō risshi ki’ and variously translated as “Moral of success” or“Foundations of learning and achievement” or “Self-made Men Worthy ofEmulation”' or “Examples of Self-made Leaders” or "Paragons of instruction and success"] |

| Artist | Kiyochika Kobayashi (1847-1915) |

| Signature |  |

| Seal | Shinsei 真生 (see above) |

| Publication Date | October 26, 1885 明治十八年 十月廿六日 |

| Publisher | Matsuki Heikichi (松木平吉) proprietor of Daikokuya Heikichi [Marks: seal not shown; pub. ref. 029] (from right to left) publishing and printing date: 明治十八年 御届 十月廿六日 [Meiji 18, notification delivered, 10th month 26th day] assigned number within series: 四五 [45] publisher information: 画工兼 出板 松木平吉 [in seal script] 両国吉川町二番地 [artist and publisher Ryōgoku Yoshikawachō 2-banchi Matsuki Heikichi han] |

| Engraver | |

| Impression | excellent |

| Colors | excellent |

| Condition | fair - margins trimmed to brocade border; staining; some backing remnants |

| Genre | ukiyo-e; rishki-e; kyōiku nishiki-e |

| Miscellaneous | print number 45 (四五); position 47 in the Table of Contents for the series |

| Format | vertical oban |

| H x W Paper | 13 5/8 x 9 1/8 in. (34 x 23.2 cm) |

| H x W Image | 13 5/8 x 9 1/8 in. (34 x 23.2 cm) |

| Literature | Kiyochika: Artist of Meiji Japan, Henry D. Smith II, Santa Barbara Museum of Art, 1988, p. 75; TheWorld of the Meiji Print: Impressions of a New Civilization, Julia Meech-Pekarik, Weatherhill, 1986, p. 123, fig. 71; The Male Journey in Japanese Prints, Roger Keyes, The Fine Arts Museum of San Francisco and The University of California Press, 1989, p. 120, fig. 172; Japan in World History, James L. Huffman, Oxford University Press, 2001, as frontispiece; The Arts of Meiji Japan 1869-1912: Changing Aesthetics, Barry Till, Art Gallery of Greater Victoria, 1995, p. 105, pl. 1.J.; Conflicts of Interest: Art and War in Modern Japan, Philip K. Hu, et. al., Saint Louis Museum of Art, 2016, p. 56, pl. 10. |

| Collections This Print | Museum of Fine Arts, Boston Accession Numbers 63.776 and 2000.268; Tokyo Metropolitan Library 280-K031; The Tsubouchi Memorial Theatre Museum of Waseda University 401-0561 (variant border color); Smithsonian National Museum of Asian Art S2003.8.1206; Ritsumeikan University, Art Research Center AcNo Z0173-377; Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco 1963.30.5310 (variant border color); Metropolitan Museum of Art JP3420; Harvard Art Museums/Arthur M. Sackler Museum 1974.10 (variant border color); The British Museum 1989,0808,0.1 (variant border color); Saint Louis Museum of Art 131:2010 |