Prints in Collection

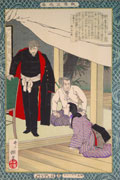

| [portraying pre-rebellion events during June 1869] IHL Cat. #481 |

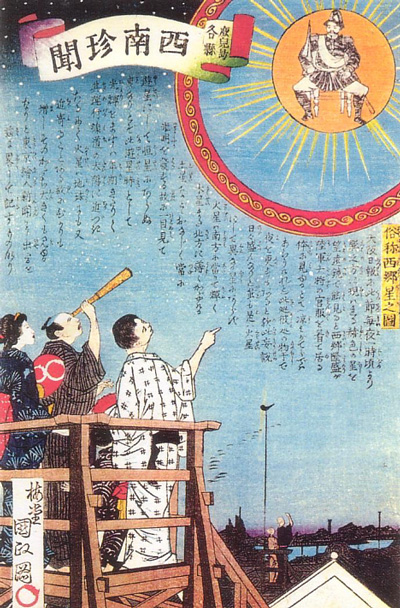

| IHL Cat. #2169 |

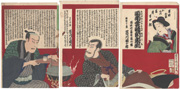

[a newspaper report]

IHL Cat. #567

True News from Kagoshima-ken,

No. 6, 1877

unknown artist

[a newspaper report - women warriors of Kagoshima]

IHL Cat. #2184

| The Debate Over Invading Korea (Seikanron), May 15, 1877 Suzuki Toshimoto (active c. 1877-1890s) [portraying pre-rebellion events of August-mid October, 1873] IHL Cat. #497 | The Arraignment of Oyama Tsunayoshi, August 27, 1877 Yōshū Chikanobu (1838-1912) [portraying events of February 1877] IHL Cat. #445 | Kagoshima senki, March 23, 1877 Yōshū Chikanobu (1838-1912) [portraying events of February-March 1877] IHL Cat. #449 |

| Illustration of the Rebels Being Suppressed at Kagoshima, October 1877 Yōshū Chikanobu (1838-1912) [portraying events of April 1877] IHL Cat. #450 | Report on the Actual Condition at the Battlefield, September 21, 1877 Kobayashi Toshimitsu (a. 1876–1904) [portraying events of September 1877] IHL Cat. #447 |  Retreat to the Defensive Position at Hyuga, May 10, 1877 Yamazaki Toshinobu (1857-1886) [portraying events of March 1877] IHL Cat. #482 |

Kagoshima Shinbun: Illustration of the Battle of Yamagaguchi, March 1877 Adachi Ginkō (active 1873-1902) [portraying evnes of March 12, 1877] IHL Cat. #1974 | Complete Chronicle of the Subjugation of Kagoshima: Illustration of Government Forces Attacking Miyazaki, March 4, 1878 Utagawa Kunimatsu (1855-1944) [portraying events during August 1877] IHL Cat. #833 |

Illustration of the Rebels Being Suppressed at Kagoshima, October 4, 1877 Illustration of the Rebels Being Suppressed at Kagoshima, October 4, 1877[portraying events of September 24, 1877] Utagawa Kunimasa IV (1848-1920) IHL Cat. #451 | IHL Cat. #448

| Presentation of the Emperor's Gift Cup for the second time to commanders involved in pacifying Western Japan (Saigoku), 1877 Utagawa Yoshitsuya II (active 1870s) [After the last of the rebel forces were decimated by the Imperial Army in late September 1877, the Emperor made sure to visit and congratulate both officers and soldiers.] IHL Cat. #684 |

| IHL Cat. #1171 |  Mr. Saigō's Amazing Charm Mr. Saigō's Amazing Charm to Ward Off Cholera, October 23, 1877 Yōshū Chikanobu (1838-1912) IHL Cat. #877 | Portrait of Kirino Toshiaki, November 21, 1877 Hasegawa Sadanobu II (Konobu I) (1848-1940) IHL Cat. #1172 |

Iwai Hanshirō VIII, Ichikawa Danjūrō IX and Ichikawa Sadanji in The Morning East Wind Clearing the Clouds of the Southwest, March 1878 Iwai Hanshirō VIII, Ichikawa Danjūrō IX and Ichikawa Sadanji in The Morning East Wind Clearing the Clouds of the Southwest, March 1878Toyohara Kunichika (1835–1900) [In March 1878 Kanya staged a dramatization of the Satsuma Rebellion, which had ended in the rebels’ defeat just months earlier.] IHL Cat. #1276 |

| [portraits of Saigō and government military officers who fought against him] IHL Cat. #508 |

Fukuchi Gen’ichirō, October 26, 1885

Kobayashi Kiyochika (1847-1915)

[The journalist Fukuchi Gen'ichirō taking notes on the battlefield during the Satsuma Rebellion]

IHL Cat. #881

[She stands at the head of the women's troops; when resting she offers help, shares out food and looks after the soldiers' needs]

IHL Cat. #479

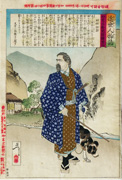

Saigō Takamori, No. 17, Saigō Takamori, No. 17,from the series Personalities of Recent Times, February 24, 1888 Tsukioka Yoshitoshi (1839-1892) IHL Cat. #926 |

| In riding through the streets one notices the crowds in front of the picture shops, which are bright in color from the war prints. The Satsuma rebellion furnishes themes for the illustrators. The pictures are brilliant in reds and blacks, the figures of the officers in most dramatic attitudes, and "bloody war" is really depicted, though grotesque from our standpoint. One of the pictures represents a star in heaven (the planet Mars), in the centre of which is General Saigo, the rebel chief, beloved by all the Japanese. After the capture of Kagoshima he and other officers committed hara kiri. Many of the people believe he is in Mars, which is now shining with unusual brilliancy. - Edward Sylvester Morse1 |

Summary

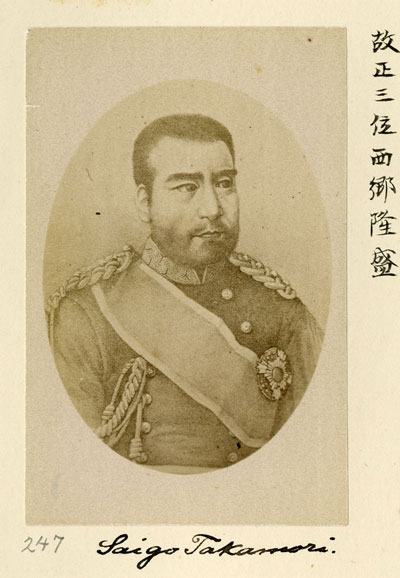

The unsuccessful Satsuma Rebellion of 1877 (also known as the Seinan War2 西南戦争), a nine month long uprising of Satsuma-based samurai against the nine year old central Meiji government, was Japan’s last civil war. Led by ex-Meiji government official and samurai Saigō Takamori 賊魁西郷 (January 23, 1827 – September 24, 1877), the rebellion resulted in the death of roughly 20,000 rebels and 6,000 government forces.

Background

With the formation of a conscript military based on European models in 1873 the samurai class of professional soldiers found itself marginalized. In Satsuma, the samurai class was particularly powerful and a strong central government issuing prescripts against many of their long-time privileges generated, at best, grudging partial compliance. With the issuance of the March 28, 1876 prescript against samurai carrying swords and an August cut in government stipends to samurai, opposition to the central government turned violent, and on October 24 two hundred radical samurai attacked and briefly held Kumamoto Castle, the Meiji government’s main military installation in Satsuma. Sporadic outbreaks continued, culminating in raids at the end of January 1877 on the government armory in Kagoshima City by students from the private samurai schools, known as Shigakko.

Saigō Takamori (1827-1877)

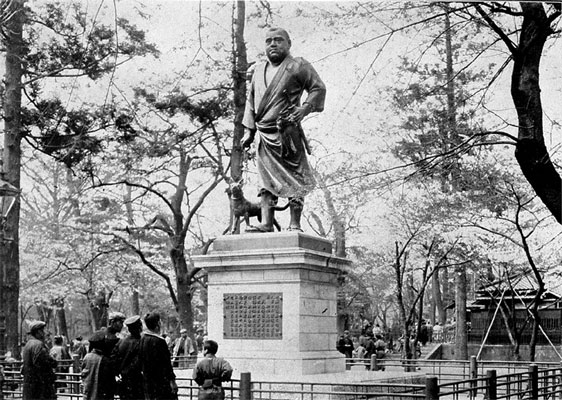

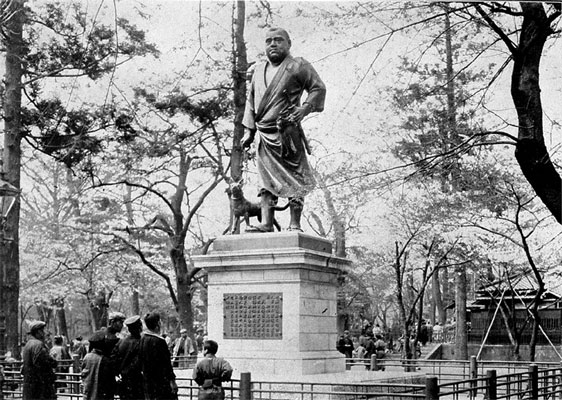

Twelve years later in 1889, as part of the celebrations around the introduction of a new constitution, Saigō was pardoned by the emperor and elevated in rank. In 1898, a bronze statue of Saigō with his faithful hunting dog was erected in Tokyo's Ueno Park. [See the print Bronze Statue of Saigō in Ueno Park.]

The Legend Continues

Source: The Japan Times Online http://search.japantimes.co.jp/cgi-bin/nn20090913a6.html

The Japan Times

Sunday, Sept. 13, 2009

Death Song Linked to Meiji Era Hero Saigo Found in Army Doctor's Diary

KAGOSHIMA (Kyodo) What may be a death song written by Takamori Saigo, a hero of the 1868 Meiji Restoration, has been discovered in the diary of an army doctor who was in the antigovernment force Saigo led in the 1877 Seinan War, it was learned Saturday.

The song, written in the traditional quatrain poetry style featuring seven Chinese characters on each line, was discovered in a diary entry made by Taisuke Yamazaki that was dated Sept. 24, 1877. That was the day when Saigo, one of most popular figures in Japanese history, committed suicide in Kagoshima during the civil war.

…[T]he author laments in the song that all the roads are blocked by enemies in the war, his life is full of both merits and demerits, and he has no face to again meet Nariakira Shimazu, the samurai who ruled over Kagoshima.

Early Government Censorship

The unsuccessful Satsuma Rebellion of 1877 (also known as the Seinan War2 西南戦争), a nine month long uprising of Satsuma-based samurai against the nine year old central Meiji government, was Japan’s last civil war. Led by ex-Meiji government official and samurai Saigō Takamori 賊魁西郷 (January 23, 1827 – September 24, 1877), the rebellion resulted in the death of roughly 20,000 rebels and 6,000 government forces.

Background

With the formation of a conscript military based on European models in 1873 the samurai class of professional soldiers found itself marginalized. In Satsuma, the samurai class was particularly powerful and a strong central government issuing prescripts against many of their long-time privileges generated, at best, grudging partial compliance. With the issuance of the March 28, 1876 prescript against samurai carrying swords and an August cut in government stipends to samurai, opposition to the central government turned violent, and on October 24 two hundred radical samurai attacked and briefly held Kumamoto Castle, the Meiji government’s main military installation in Satsuma. Sporadic outbreaks continued, culminating in raids at the end of January 1877 on the government armory in Kagoshima City by students from the private samurai schools, known as Shigakko.

Saigō Takamori (1827-1877)

| Saigō Takamori was a revered figure to many Japanese. Physically he was imposing, standing six feet tall and weighing 200 pounds. He was a key player in the formation of the Meiji government, both as a military leader against the Tokugawa shogunate (see the print Surrender of the Ezo rebels) and as a politician shaping foreign and domestic policies. After his leaving service with the Meiji government, largely over differences on Japan’s Korea policy, [see the print The Debate Over Invading Korea (Seikanron)] he returned to his home province of Satsuma where he cultivated his image as “a man of virtue, culture, and honor” and where he was generally regarded as a “living legend.”3 While not actively engaged in politics he remained politically involved through the Shigakkō (private samurai schools), where he was “celebrated as the spiritual leader.”4 While he is viewed by historians as a reluctant leader of the rebellion his reputation made him the natural leader. After a raid on the government arsenal by Shigakkō students, his hand was forced and on February 7, 1877 he announced his decision to “confront the central government.”5 Nine months later the rebellion was over, Saigō was dead and his out-manned and out-gunned rebels decimated. |

The Legend Continues

Source: The Japan Times Online http://search.japantimes.co.jp/cgi-bin/nn20090913a6.html

The Japan Times

Sunday, Sept. 13, 2009

Death Song Linked to Meiji Era Hero Saigo Found in Army Doctor's Diary

KAGOSHIMA (Kyodo) What may be a death song written by Takamori Saigo, a hero of the 1868 Meiji Restoration, has been discovered in the diary of an army doctor who was in the antigovernment force Saigo led in the 1877 Seinan War, it was learned Saturday.

The song, written in the traditional quatrain poetry style featuring seven Chinese characters on each line, was discovered in a diary entry made by Taisuke Yamazaki that was dated Sept. 24, 1877. That was the day when Saigo, one of most popular figures in Japanese history, committed suicide in Kagoshima during the civil war.

…[T]he author laments in the song that all the roads are blocked by enemies in the war, his life is full of both merits and demerits, and he has no face to again meet Nariakira Shimazu, the samurai who ruled over Kagoshima.

Early Government Censorship

The outbreak of the rebellion is generally given as January 29, 1877 when "students", really samurai who attended Saigō's private schools (Shigakko), raided the government arsenal at Sōmuda in Kagoshima. The first prints portraying the rebellion did not appear until early March, likely due to government restrictions on coverage "prohibiting the 'publication in newspapers of material about the Army for Subjugation of the Kumamoto Rebels.'"6 It was not until February and later in May that restrictions were eased requiring only "authorization" or "permission" prior to publication.

Woodblock Prints

Throughout the revolt the conflict was chronicled, sensationalized, mythologized and, finally, its leader Saigō was deified by woodblock publishers and artists. Woodblock prints issued in the hundreds depicting bloody battle scenes, strategy meetings and, ultimately, Saigō’s death and “ascendance to heaven” were eagerly bought by the public. Constructed from their imaginations and newspaper reports, well-known artists such as Yoshitoshi, Kunichika, Chikanobu, Yoshitora, Toshinobu, Kunimasa IV and lesser-known artists such as Toshimitsu, Kunimatsu and Toshimoto churned out prints in the tradition of the great warrior prints of the earlier Edo-period.

Baido Kunimasa, Curious Southwestern Stories of Kagoshima Prefecture: The “Saigo Star”

"Toward the end of the Satsuma Rebellion, an unfamiliar red star shone in the night sky, and rumors circulated that the star must be an incarnation of Saigo Takamori, who was leading the rebellion. One of the stories went that with the help of a telescope you could see Saigo himself within the star. The controversy culminated to the point that newspapers had to report that the star was simply Mars appearing close to Earth."7

"Toward the end of the Satsuma Rebellion, an unfamiliar red star shone in the night sky, and rumors circulated that the star must be an incarnation of Saigo Takamori, who was leading the rebellion. One of the stories went that with the help of a telescope you could see Saigo himself within the star. The controversy culminated to the point that newspapers had to report that the star was simply Mars appearing close to Earth."7

These Satsuma Rebellion prints would serve as a model for the thousands of prints produced during the 1894-1895 Sino-Japanese War and the 1904-1905 Russo-Japanese War.

1 Japan Day By Day, 1877, 1878-79, 1882-83, Volume 1, Edward Sylvester Morse, Houghton Mifflin Co., 1917, p. 269.

2 Translated as the "West-South War" (Seinan no eki).

3 The Last Samurai: The Life and Battles of Saigo Takamori, Mark Ravina, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2004, p. 196.

4 Ibid., p. 197.

5 Ibid., p. 201.

6 Creating a Public: People and Press in Meiji Japan, James. L. Huffman, University of Hawaii Press, 1997, p. 95-96.

7 Waseda University Library http://www.wul.waseda.ac.jp/kosho/bunko10/b10_8333/index.html

last revision:

7 Waseda University Library http://www.wul.waseda.ac.jp/kosho/bunko10/b10_8333/index.html

last revision:

8/6/2019