About This Print

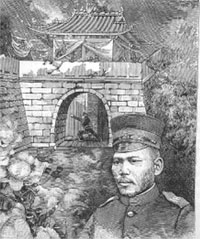

Depicting private Harada Jūkichi who scaled the walls of the Gembu Gate fort and opened the gates for his comrades in arms. For another print depicting Harada see IHL Cat. #845 Picture of the First Soldier on Top of Pyongyang Gate.

Saga of Harada Jūkichi

Source: Impressions of the Front: Woodcuts of the Sino-Japanese War, Shunpei Okamoto, Philadelphia Museum of Art, 1983, p. 24Pingyang (Pyongyang) was well protected by walls that had to be surmounted in order to conquer the city. Repeated frontal attacks by the Japanese failed to penetrate, even after exhausting all their ammunition. One volunteer in the Eighteenth Regiment, twenty-seven year-old Harada Jukichi of Aichi prefecture, a mild man with a wife and a daughter, saw his regiment fail three times to penetrate the fortification and fearlessly scaled the wall of Gembu Gate. Harada lowered himself into the midst of the enemy and opened the gate from within. His comrades them flooded into the enemy fort. Harada's action was considered so meritorious that he was immediately promoted to the rank of superior private. Harada's deed was widely celebrated in poems and prose. A particularly famous song includes this verse:

Diving under bullets thicker than rain,

he scrabbles up the castle wall,

like a monkey and lightly jumps inside;

this man is none other than Mr. Harada Jukichi

following him, platoon commander Mimura

Harada received the Order of the Golden Kite for his feat, but his honor proved overwhelming. He began a life of drunken dissipation and later was employed in the theater district reenacting his deed of heroism at Gembu Gate. The military authorities are said to have rebuked him for soiling the honor of the imperial army. It is also said that the soldier who actually climbed the gate first was Matsumura Aktaro, not Harada. Since Harada had already been decorated, this embarrassing fact was silenced. Matsumura was intimidated by the authorities and did not disclose the incident but secluded himself in his father's antique shop seeking truth among the collection of antiques.

Source: The Sino-Japanese War, Nathan Chaikin, self-published, 1983, p. 73

As soon as Colonel Sato saw that Peony Mount had been taken, he directed his efforts against the Genbu Gate (Genbumon), the nearest on that side of the city. The Chinese defended the walls so well and kept up such a brisk fire that the Japanese assault was repulsed. The soldiers were reluctantly retreating, regretting the wasted lives of their brave comrades. At this moment, Lieutenant Mimura burning with shame at the repulse, shouted to his men: “Who will come with me to open that gate?” and at once rushed forward. Harada, one of his men, then said: “Who will be the first to the wall?” and flew after his officer. They ran so quickly that only eleven other soldiers were able to join them under the wall after passing through a rain of lead. Mimura and his small band of heroes found the gate too strong to be forced, so the Lieutenant gave orders to scale the walls. The Chinese were busy firing in front, keeping the Japanese back, never imagining that a handful of men would have the boldness to climb the walls like monkeys under their very eyes. Mimura and his men came upon them with such surprise that they were scattered in an instant.

Source: http://www3.la.psu.edu/textbooks/MJ/ch7_main.htm (note website is no longer active)

Perhaps second only to Shirakami/Kiguchi in terms of popular fame was Private First Class Hirada Jukichi. Like Private Onoguchi, Harada won fame by a daring and dangerous attack on a fortified gate during the Japanese attack on Pyongyang. Harada did not use explosives. Instead, he scaled the gate, dropped down inside the compound, and opened it for the Japanese soldiers to rush in.

Private Harada, too, was a man of humble origins whose heroism was celebrated in song, verse, and images. His deeds earned him the Order of the Golden Kite, the highest military honor. But fame did not sit well with Harada. He sold his medal, drank the proceeds, and ended up eking out a living by re-enacting his assault on the gate on stage. His last known performance was in 1900.

There is an even stranger twist to Harada's story. It turns out that a secret suicide squad had already entered the Chinese fortress the night before the general assault. One member of this squad, Matsumura Akitarô, although presumed dead, survived and made his way back to Japan. By this time, Harada was already the celebrated hero of the battle. To avoid lessening Harada's glory (and perhaps with the Shirakami-to-Kiguchi matter in mind), the military authorities forbade Matsumura to disclose his role in the battle. Matsumura apparently suffered from depression for the rest of his life but did finally tell his tale to relatives upon his deathbed in 1945.

The following points summarize the characteristics and significance of the major public heroes of the First Sino-Japanese War:

- They were all men of humble social origins and low rank.

- Although the material importance of their deeds varied, they became heroes because of their qualities of loyalty, courage, and dedication to duty as an imperial subject.

- The broader message, therefore, was that all Japanese, civilian or military and no matter their circumstances, can be heroes to their nation by sincerely doing their duty without complaint. Factory workers, for example, should not go on strike for higher wages.

- Insofar as ordinary people took this message to heart (and the precise extent is hard to say), the war helped to make Japanese for whom sacrifice for the nation (or, more concretely, the emperor) was the highest calling in life. But bear in mind the qualifying clause "insofar as ordinary people took this message to heart." Not everyone who heard the praises of these heroes--and not even everyone who sung the praises of these heroes--necessarily sought to emulate their example.

Print Details

| IHL Catalog | #93 |

| Title or Description | Harada Jūkichi Opens the Genbu Gate (Hyonmu) from within the Fort at Pyongyang (Heijō) 平壌激戦玄武門攻撃ノ際清兵嶮ニ據テ善ク防御シ日軍頗ル苦戦ス時ニ一勇兵アリ城壁ヲ乗越遂ニ関門大勝、倚テ古今ノ大功ヲ顕ス此人ハ誰ソ三河国住人歩兵一等卒原田重吉氏則是ナリ [per the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston] |

| Artist | Mizuno Toshikata (1866-1908) |

| Signature |  応需 年方作 |

| Seal | Toshikata 年方 |

| Publication Date | 1894 (Meiji 27) |

| Publisher | 関口政治郎 Sekiguchi Masajirō (or Seijirō). Kyobashi-ku |

| Impression | excellent |

| Colors | excellent |

| Condition | good - three panel joined; trimmed into the image; center fold center panel |

| Genre | ukiyo-e; senso-e (Sino-Japanese War) |

| Miscellaneous | |

| Format | vertical oban triptych |

| H x W Paper | 13 7/8 x 27 7/8 in. (35.2 x 70.8 cm) |

| Literature | The Sino-JapaneseWar, Nathan Chaikin, self-published, 1983, p. 73, pl. 145; Japan Awakens: Woodblock Prints of the Meiji Period (1868-1912), Barry Till, Pomegranate Communications, Inc., 2008, p. 95. |

| Collections This Print | Museum of Fine Arts, Boston RES.27.202a-c and 21.1786-8; Art Gallery of Greater Victoria 1991.042.007; British Library shelfmark: 16126.d.1(53) |

last revision:

3/7/2020