Prints in Collection

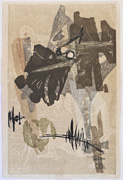

Wind in the Body, 1955IHL Cat. #132

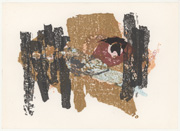

Passing Nun (Buddhist), 1958IHL Cat. #159

Nostalgia of Kyoto, 1960

IHL Cat. #1647

Early Spring, 1963

IHL Cat. #200

Musician Greenwich Village, 1964IHL Cat. #238

Musician Greenwich Village, 1964

IHL Cat. #2240

Kyoto's Voice, 1964IHL Cat. #239

IHL Cat. #287

Wind, 1964

IHL Cat. #422

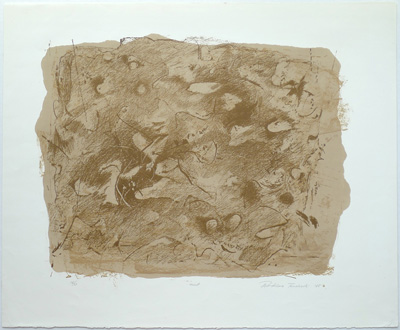

Nest, 1965 (lithographic print)

IHL Cat. #720

Tea Ceremony, 1965

IHL Cat. #218

Work A, 1966IHL Cat. #189

IHL Cat. #190

Spring Garden, 1974

IHL Cat. #225

IHL Cat. #224

Early Spring Garden, 1977

IHL Cat. #198

NIWA (Sunshine), 1978

IHL Cat. #281

NIWA (Winter Scenery), 1978

IHL Cat. #282

Good by Winter, 1984

IHL Cat. #1060

NIWA (Movement) B2, 1985

IHL Cat. #604

The Letter (From Southern Italy),

1985

IHL Cat. #587

The Letter (From New York),

1985

IHL Cat. #586

NIWA (Nunnery), 1985

IHL Cat. #1692

Garden in Kyoto, 1986

IHL Cat. #607

Biographical Data

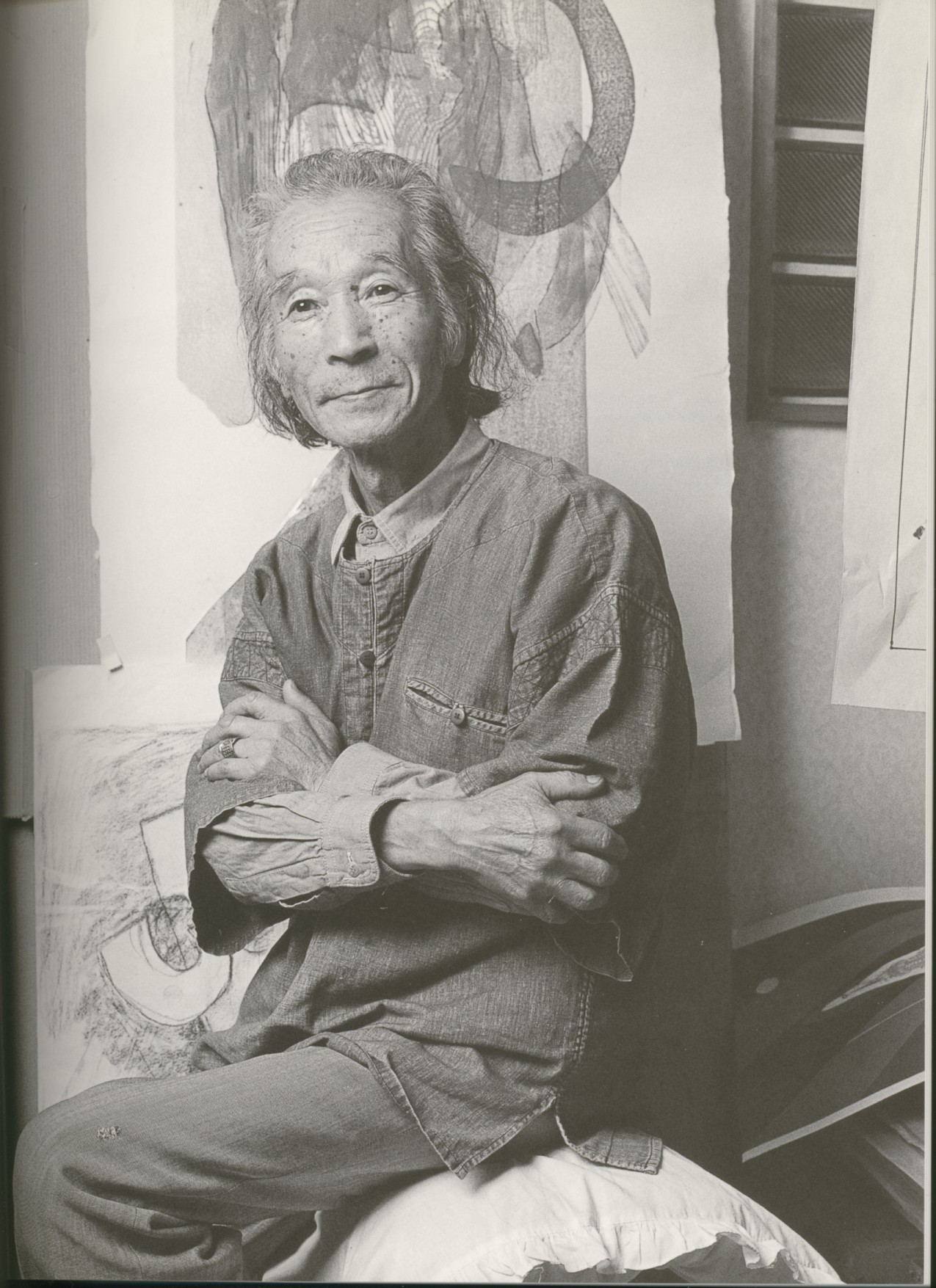

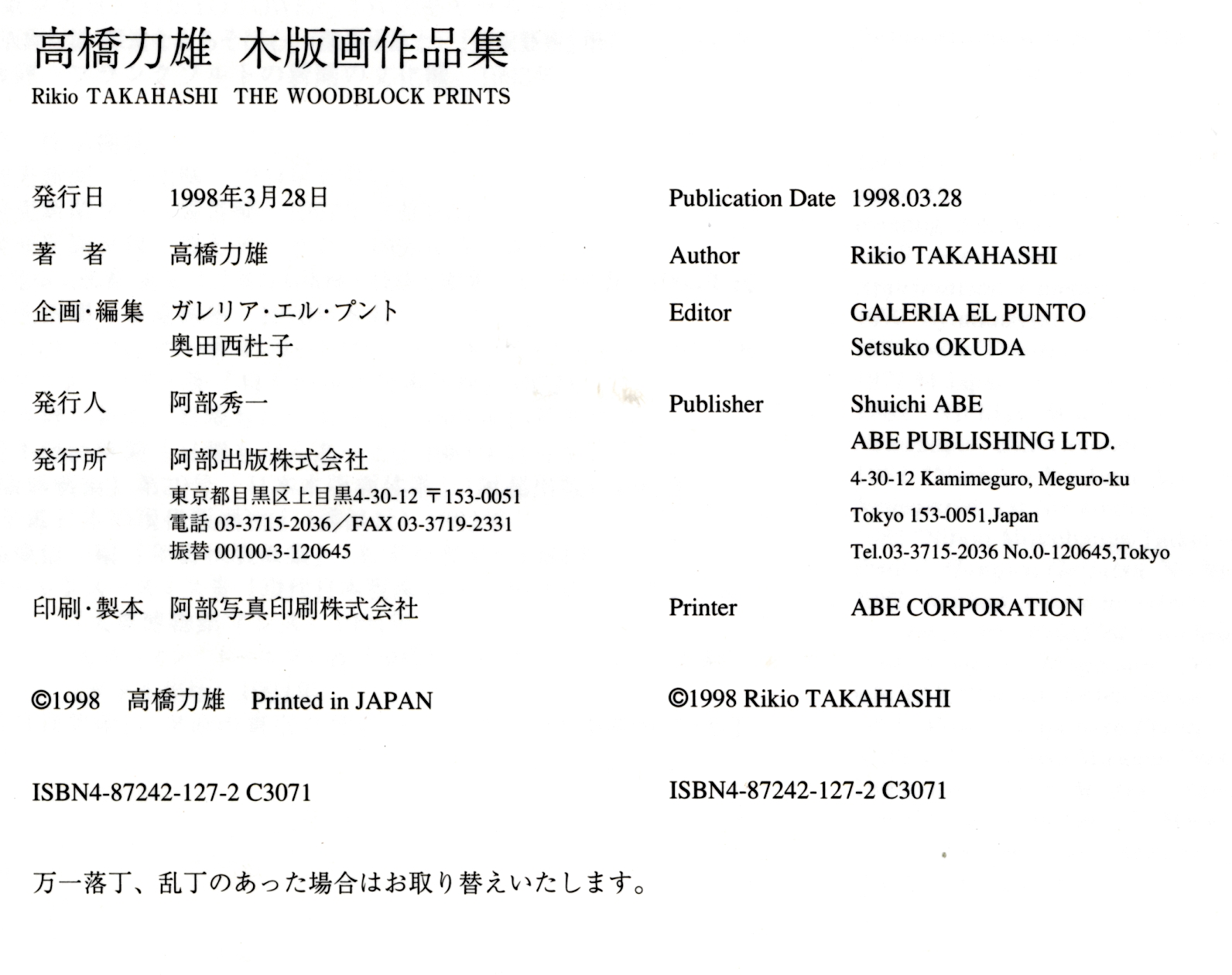

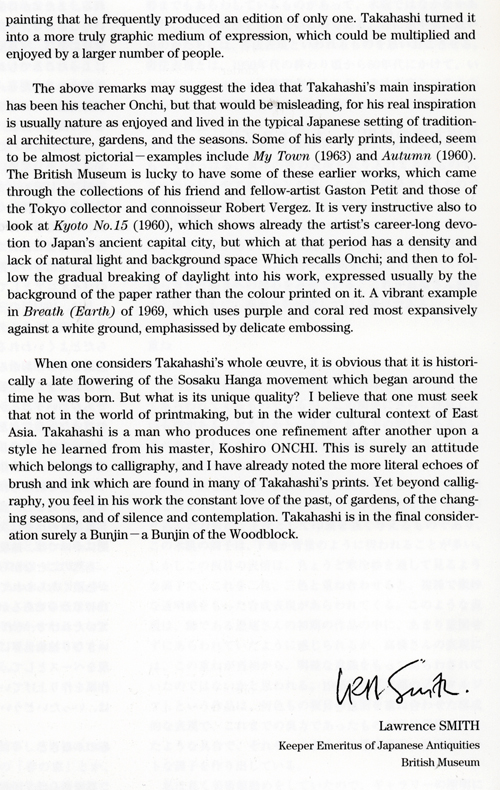

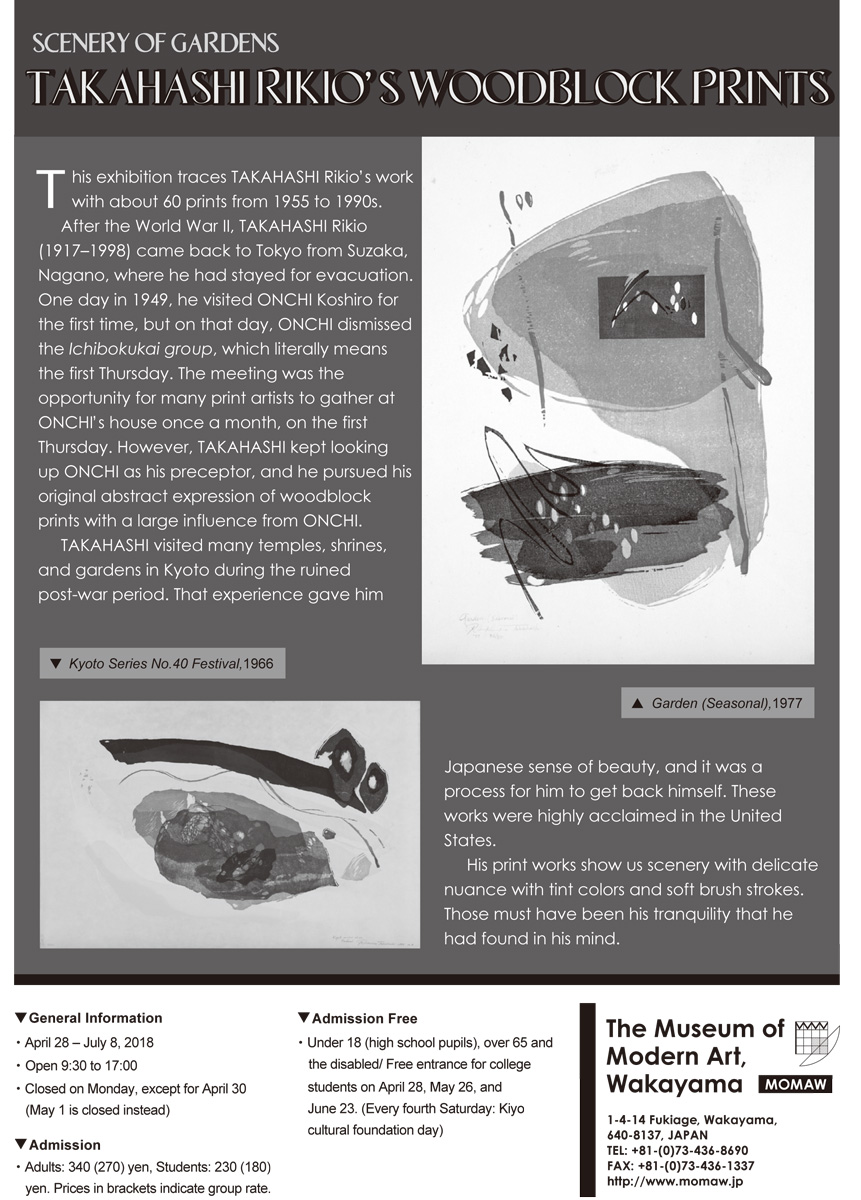

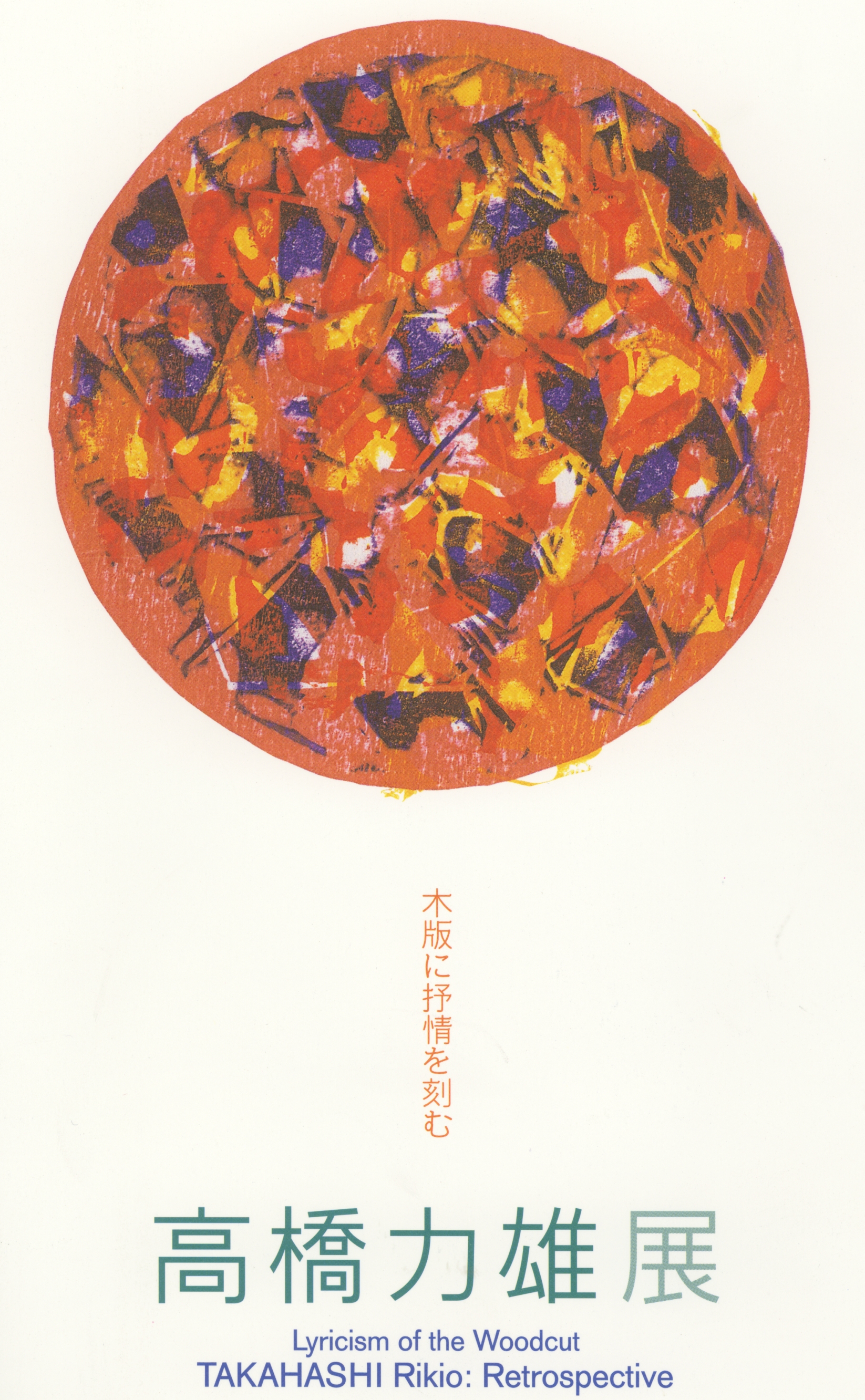

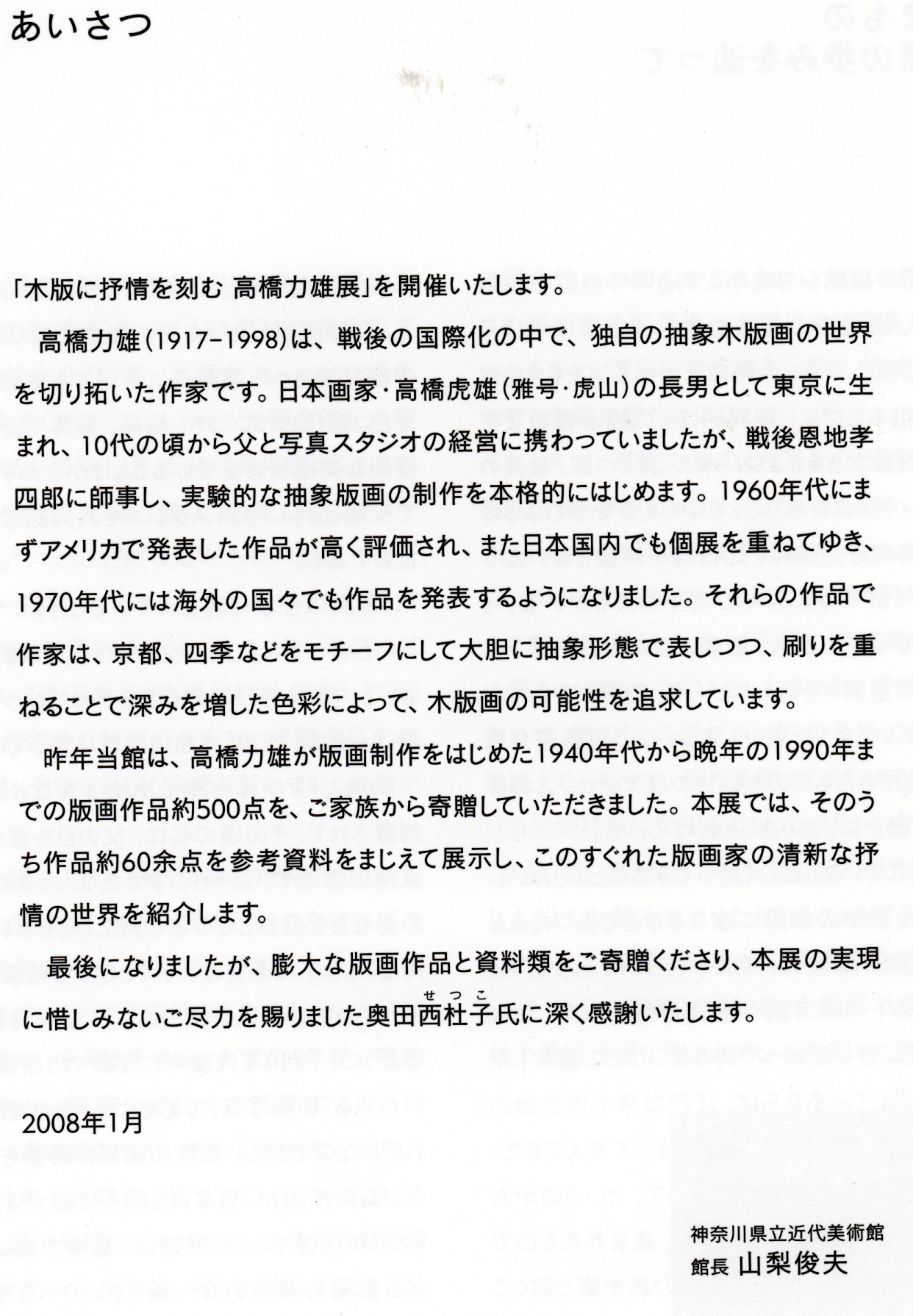

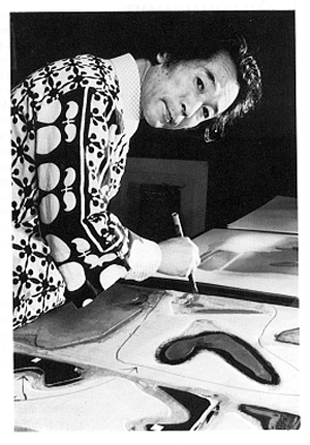

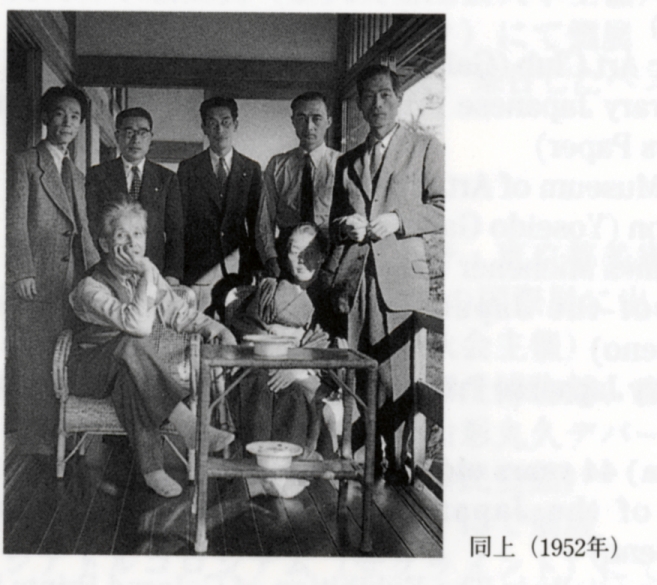

ProfileTakahashi Rikio 高橋力雄 (1917-1998 December 23) Rikio Takahashi specialized in depicting the forms of the Japanese garden, especially the classic gardens of Kyoto. He was the son of a 'Nihonga' ("Japanese-style painting") artist and from 1949-1955 became an important pupil of the seminal figure in modern Japanese printmaking, Onchi Kōshirō (1891-1955),whose late non-representational style had a significant influence. Takahashi studied at the Chouinard Art Institute [later to become integrated into the California Institute of Arts] in 1962 and 1963 and returned to the United States several years later to work with Ken Tyler at Tyler's renowned Gemini print studio. (See "Collaboration with Ken Tyler," below.) Takahashi is one of the last true sōsaku hanga (creative print) artists. He successfully explored in an abstracted manner various forms found in gardens and nature. He is especially adept at the subtle partial overlay of one or more colors to create varied opacities and textures as well as complexity of shapes. Many of his prints evoke an atmosphere of stillness and balance that have a sense of timelessness. Takahashi's prints vary in size, with some reaching roughly three feet in height. BiographySource: Modern Japanese Prints 1912-1989, Lawrence Smith, The British Museum Press, 1994, p. 35-36 and Rikio Takahashi, The Woodblock Prints published by Abe Publishing LTD., 1998, p. 199-205.Takahashi was born in in 1917 at Honjo Wakamiyacho, Tokyo. His father Tarao was a Nihonga (Japanese style) painter, and his uncle was Imaizumi Toshiji, a Yōga (Western style) artist, from whom he first learned art. He failed to graduate from middle school and at the age of 17 he was co-managing, with his father, the family's photographic studio. In 1944 he married Sekino Shizu. In that same year he was conscripted as a photographer by the Navy. In 1945 his first daughter Setsuko was born, followed by his first son Mitsunori in 1946. Takahashi quotes his artistic education as having taken place at the California Institute of Art in the 1960s, when he spent two years in the USA (1962-63). By then, however, he had studied informally for six years (1949-55) with Onchi Kōshirō (1891-1955). His early works are very close to Onchi's late abstract style, with much use of heavily grained driftwood and strongly contrasted colours. Gradually his printing became smoother, his prints very large, and his colours more internally harmonious. His works have been inspired mostly by Kyoto gardens and locations, and are in a sense almost calligraphic reworkings of a few themes in a semi-abstract style. Takahashi has exhibited with the Japanese Print Association since 1950 and since the mid-1960s with the College Women's Association of Japan annual show. After his USA visit he had many one-man shows in that country and became popular in the West.  Photo with Onchi Kōshirō 1952. Takahashi is standing on left. From artist's catalogue raisonné p.199. Printing TechniqueSources: Who's Who in Modern Japanese Prints, Frances Blakemore, Weatherhill, 1975, p. 197 and Modern Japanese Prints 1912-1989, Lawrence Smith British Museum Press, 1994, p. 62 Takahashi’s use of the traditional woodblock medium is accomplished in a particularly unique fashion. He partially overlaps shina-faced (veneer) plywood blocks and prints with thin watercolor ink, creating distinct tones. In order to preserve the integrity of the colors, each block is printed partly over a white area. The darker tones are usually the result of several overlappings, but this is not always the case. The textures, worked out in advance, enhance the translucency of the pigments. The bold, dark stripes are softened by expanses of varying hues. “Takahashi Style”Source: "The World of Rikio Takahashi – The Spirit of Wood,” Masayoshi Homma, in Rikio Takahashi, The Woodblock Prints, Abe Publishing LTD. (1998) pp.18-21.Takahashi became immersed in abstraction right from the beginning, jumping directly into abstraction without going through a representational phase. Building on this foundation, he developed forms unique to himself and created the distinctive Takahashi Style. What, then, are the features of this style? Simply stated, he added essential qualities cultivated in Japanese tradition to the modern abstract style learned from Onchi to create a new and unique style of his own. Takahashi almost never uses colors close to the primaries. He uses an abundant variety of subdued mixtures, subtle variations of warm browns, cool water tones, and greens resembling the feathers of the bush warbler greens. These are all colors typical of Kyoto. Their constant luminous quality is a characteristic of Takahashi’s work that might be considered a reflection of the calm and elegant Yayoi aspect of the Japanese spirit. Beginning in 1970, there was a sudden appearance of bright areas of red and red accents that give a finishing touch to the composition. There are brief glimpses of a free spirit which break the tension of carefully-maintained balance. In Takahashi’s prints, varied, irregular forms are arranged inside and outside a large square. Some of them seem to have been created with a brush and have a sense of motion which is quite difficult to achieve in woodblock prints. The black and dark-colored forms in particular are reminiscent of Japanese calligraphy. I would like to call attention to Takahashi’s special technique of overlapping colored areas to create effects that might be thought to belong more to the category of color than form. When a woodcut is printed, the delicate texture of the wood grain appears as if a fine mist had been sprayed on the surface. However, the cuts made by the knife in the block play a central role, and the grained surface is generally treated as background. When two or three colors are overlapped, the grain may appear as if seen through a layer of gauze, resulting in a composite expression with a complex and subtle transparency. This sort of expression can be seen in some of Onchi’s early work but it seems to have been unintentional. Takahashi, on the other hand, used this layering effect quite deliberately throughout his career. This layering of colors is an important factor in the consistency of his style from the early period to present. This subtle transparent expression depends on a marvelous technique of printing in extremely thin layers like the thin strips of meat in shabushabu, but it also relies on the conditioning of the colors. In any case, this technique is the secret behind the maintenance of color brightness in spite of layering and the subtlety of the neutral colors produced. CompositionThe layers of colors and forms are organized in unique compositions. This compositional style belongs mainly to the Yayoi tradition of Japanese art. However, between the fifties and sixties it also had some of the more expressive, free-flowing qualities of the Gemini tradition. Irregular forms were spread over the entire surface of the picture with Dionysian abandon. This resulted in truncated compositions with a somewhat anxious dynamism. Beginning in the mid-sixties, a white space appeared around the motif reminiscent of the blank areas in ink painting. In the seventies this margin was even more evident, enhancing the light, bright qualities of the print. This change represented an assertion of Yayoi taste over Gemini.

Critical CommentsSource: Modern Japanese Prints 1912-1989, Lawrence Smith, British Museum Press, 1994, p. 62Takahashi, like many Japanese artists of the post-war era, found a theme and has kept to it, endlessly exploring and refining over more than forty years his prints inspired largely by the classic gardens of Kyoto. Unlike most, however, his concentration on virtually one theme has led to ever-greater depth and ease, each print very subtly yet unequivocally creating a different little world of colour and mood. These colours reflect not only the quiet tones of the gardens themselves but the almost imperceptible changes in light which the seasons bring. The same atmosphere is found even in his prints which do not refer specifically to gardens. Source: Rikio Takahashi – Hangi no Bunjin, Lawrence Smith, in Rikio Takahashi, The Woodblock Prints, Abe Publishing LTD. (1998) pp. 12-13. When one looks at Takahashi’s prints over four decades, there is also this constant sense of precision, as if he knew exactly what he wanted to achieve before he even began to cut the block. Takahashi’s main inspiration…is usually nature as enjoyed and lived in the typical Japanese setting of traditional architecture, gardens, and the seasons. Takahashi is a man who produces one refinement after another upon a style he learned from his master, Koshiro Onchi. This is surely an attitude which belongs to calligraphy, and I have already noted the more literal echoes of brush and ink which are found in many of Takahashi’s prints. Yet beyond calligraphy, you feel in his work the constant love of the past, of gardens, of the changing seasons, and of silence and contemplation. Takahashi is in the final consideration a Bunjin (a scholar) – a Bunjin of the Woodblock. Collaboration with Ken TylerSource: National Gallery of Australia website, "Artist Profile" by Gwen Horsfield, 2008 - http://nga.gov.au/InternationalPrints/Tyler/DEFAULT.cfm?MnuID=2&ArtistIRN=22711&List=True"Takahashi’s collaboration with Kenneth Tyler1 followed a strong tradition of artistic exchange between America and Japan in the post-war period. Titled Nest, the print in the NGA collection was produced at the Gemini workshop in 1965. It is representative of Takahashi’s typical mode of abstraction, with depth created by tonal layers and the image vaguely reminiscent of the natural forms Takahashi found so inspiring." 1 Source: National Gallery of Australia website http://nga.gov.au/InternationalPrints/Tyler/Default.cfm?MnuID=10 Tyler established the print workshop Gemini Ltd. in 1965 and set out to work with the very best artists of his day, promising them: ‘Here is a workshop, there are no rules, no restrictions, do what you want to do’ The Artist's Words - “On My Work”Source: Reflections on the Path of Printmaking, Rikio Takahashi in RikioTakahashi, The Woodblock Prints, Abe Publishing LTD. (1998) p. 197.It is impossible to speak about my work while looking at a book orphotographic reproductions of it. It is like scratching a place that itches while wearing an overcoat. Flat printed reproductions are different from the actual work. My prints are made with the water-based mineral pigments called suihi, which are used in Japanese-style painting, on handmade Japanese paper. The pigments are rubbed into the physical volume of the paper with a baren, and this produces an effect essentially different from a picture printed flat and clean with a machine. Also, the colors in the reproduction are always slightly different from those in the original. All forms of Japanese culture are structured as a do, a way or path. The prescribed path must be taken to approach these practices – kendo (the way of the sword), judo (the soft way of wrestling), shodo (the way of writing), kado (the way of flowers), kodo (the way of incense), and sado (the way of tea.) However, there is no do in my work. I amhoping to convey something true, hopefully not something false or pretentious. BibliographyCatalogue Raisonné - Rikio Takahashi, The Woodblock Prints, Abe Publishing LTD. (1998)Images of a Changing World: Japanese Prints of the Twentieth Century, Jenkins, Donald, Portland Art Museum, 1983, p. 102 and 126. Modern Japanese Prints 1912-1989, Lawrence Smith, The British Museum Press, 1994, p. 35-36. The Japanese Print Since 1900: Old Dreams and New Visions, Lawrence Smith, The British Museum Publications Ltd., 1983, p. 119 and 129. Catalogue Raisonné - Rikio Takahashi, The Woodblock Prints, Abe Publishing LTD. (1998)

Lawrence Smith (Keeper Emeritus of Japanese Antiquities - British Museum) Article p. 12 -13

ExhibitionsParis, France--one-man show; CWAJ Exhibits, Tokyo, Japan--1962- 1997;Dusseldorf, Germany--one man show; International Print Exhibition Taipei, Taiwan--prize winner; San Diego, California--one-man show; Kyoto, Japan--one man show; Xylon International Woodblock Triennial, Switzerland--prize winner in 1984 & 1990; Japan Print Association, Tokyo; Krakow International Print Biennial, Poland; New York City--one man show; Museum of Modern Art, Kamakura & Hayama, January 2008“ Lyricism of the Woodcut Takahashi Rikio: Retrospective”; Portland Art Museum, Portland, Oregon, November 2018 through March 2019 "Three Masters of Abstraction: Hagiwara Hideo, Ida Shōichi and Takahashi Rikio." Three Masters of Abstraction: Hagiwara Hideo, Ida Shōichi and Takahashi Rikio November 3 - March 31, 2019 Portland Art Museum, Portland Oregon Source: Portland Art Museum, Portland, Oregon https://portlandartmuseum.org/exhibitions/three-masters-of-abstraction/

|

ihl cat 1059 my print thumb web.jpg)